Here’s Johnny

Henry Bushkin writes about his complicated relationship with the late Johnny Carson, his friend, client, and confidante.

By Lary WallaceFebruary 24, 2014

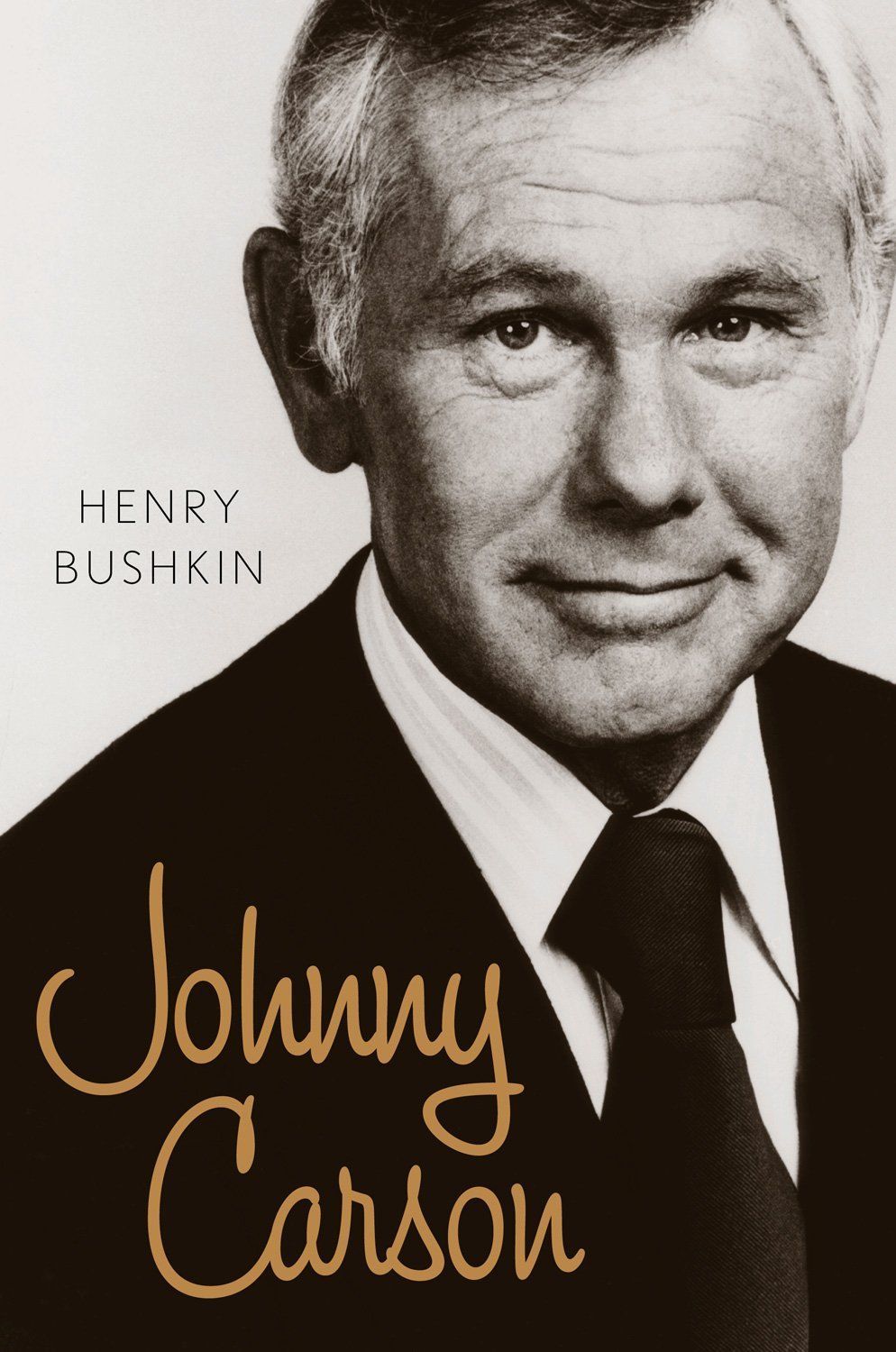

Johnny Carson by Henry Bushkin . 304 pages.

JOHNNY CARSON WAS GETTING bombed on Tanqueray and spilling his guts to his new young lawyer,Henry Bushkin. They were hanging out at a restaurant called Jilly’s, in New York, having only recently returned from the apartment that Carson’s second wife, Joanne, was apparently using as a love nest for an affair with Frank Gifford. Carson was paying for the apartment, so it’s understandable that he’d have been especially upset by this behavior from Joanne (not to be confused with Joanna, his third wife, or Jody, his first; none of these three would be his last). Carson had gone in packing a pistol, prepared for trouble, and even though he didn’t find trouble, exactly, what he found was plenty troublesome, and troubling.

Carson talked on, often lamentably, about a whole range of topics: Frank Sinatra (Jilly’s best customer); Joanne (“Maybe I drove her to it”); his kids (“I’m a shit […] I don’t see any of them”); Nebraska (“Bad weather […] Tough as nails, the people from Nebraska”); his mother (“There is no goddamn way to please that woman [...].My marriages f ailed because she fucked me up.”); Bushkin’s marriage (“[B]e careful because women will take anything they can.”); Bushkin’s missing Heineken (“Have a drink, Henry. I’m not finished yet.”); Carson’s mother again (“She deprived us all of any real goddamn warmth.”); smoking, drinking, sex, marriage (“I can’t quit smoking and I get drunk every night and I chase all the pussy I can get. I’m shitty in the marriage department”); Frank Gifford (“That guy plays three positions on the field. I could never get Joanne to go for more than two.”)

When Bushkin woke up later that morning, it was Carson on the phone. “Hey, what did we talk about last night? What the hell did I say?” Buskin told him not much. Carson, “impressed that my discretion extended even to him,” told him never to repeat any of it, and then he asked again. This time Bushkin told him, and then he said, “But if you’re worried, just realize that I’m your lawyer; everything that is said between us is confidential and covered by attorney-client privilege. I would lose my license if during your lifetime I repeated it to a soul.”

You don’t have to be a lawyer to spot the escape clause in that reassurance. Maybe Carson simply considered himself immortal and therefore saw no personal relevance in Bushkin’s qualification. He’d be forgiven for making that mistake, given the inhuman nature of his fame. But if there’s one thing Bushkin demonstrates with his new memoir, Johnny Carson, it’s that Carson was in fact mortal, maybe even human.

Bushkin got plenty close enough to know, repeatedly and over many years, as Carson’s “attorney, agent, personal manager, business manager, public relations agent, messenger, enforcer, tennis partner, and drinking and dining companion.” And although, in their business relationship, “Johnny always had the final say,” “he almost always accepted my recommendations.” On a more personal level, Bushkin “was privy to his finances, to the ups and downs of his marriages, to his concerns about his children, to all his interests and his moods, and I traveled with him every few weeks when he went on the road to play nightclubs.” They were friends, but even then Bushkin was wise enough to realize that “it wasn’t a friendship of equals.”

Their partnership and friendship ended simultaneously and far from amicably, when Bushkin did some negotiating on behalf of Carson’s company behind his back, and Carson, with characteristic coldness and finality, terminated their relationship. Bushkin was devastated by the loss of this friendship, and by the loss of income (before he was finally able to sue for some of it back). Now Bushkin, close to a decade after Carson’s death, wants to tell the whole complex and intimate story of “the most thrilling, fun, frustrating, and mysterious relationship of my life.” Bushkin also “like[s] to believe that [Carson] would have been happy with this book.”

That’s asking a lot, maybe too much; Carson never was amenable to those intent on capturing his “complexity,” let alone “his failures and shortcomings and even cruelties.” Nevertheless, that’s precisely what Bushkin, by explicit design, has done here, succeeding splendidly. When he writes with a bittersweet tenderness about his old boss, he’s never afraid to go heavy on the bitter. Writing about Carson as a recreational tennis player, for instance, he’s able to capture something fundamental about his approach to friendships. He tells the story of the time baseball great Hank Greenberg (a friend of Bushkin’s) got Carson a coveted sponsorship to join the Beverly Hill Tennis Club, and how Greenberg “very soon tired of Johnny’s curses and self-serving line calls.” After a while, Greenberg began declining Carson’s invitations to play. So did nearly everyone else: “Johnny had such a mystique […] that no one would ever question any of his line calls, no matter how egregious they seemed; people just didn’t play with him anymore.” What else could they do? To approach the situation in a more assertive manner would have been to invite retribution. And as for Carson, there’s not much he could have done either, by that point, except to quit going to the Beverly Hills Tennis Club altogether. Which is what he eventually did.

Bushkin is able to write that “Johnny Carson was one of the most generous people I’ve ever known,” but has to qualify this statement with the proviso that “Carson hated being obliged to do something, and he resented being needed, especially by people close to him. It almost automatically brought out a harshness in him, a nastiness.” When Rick, the second of Carson’s three sons, was committed to a mental asylum following a drug-and-alcohol-induced breakdown, Carson refused to see him in the hospital (“Think of the media attention!”), and sent Bushkin instead. But when, years later, Rick died in a car accident, Carson (braving the media attention) grieved publicly at the end of his show one night. Bushkin’s verdict — “In his own twisted, dysfunctional way, Johnny was a very loyal father” — tends to contradict a statement he makes earlier in the book where he writes, “[I]t’s true that by any standard Johnny was not a very good father.”

It’s all very confusing, and Bushkin, apparently, is suitably confused. You will be too. Momentarily forgetting his self-confessed unsuitability to marriage, Carson foreswore signing a prenuptial agreement upon marrying his third wife, Joanna. “[T]his romantic gesture,” Bushkin writes, “would cost Johnny $35 million” when the couple got divorced. But Carson’s gallantry was like that, often showing up suddenly and resplendently before disappearing again. When he and Joanna were still married, Carson received a note threatening harm to a member of his family if Carson didn’t personally deliver a quarter-million in cash to a specified location. When the police were called, they insisted on being the ones to make the drop; Carson insisted otherwise, reminding them that even though it would be safer for him, Johnny Carson, if they made the drop, it certainly wouldn’t be safer for his wife and son, which is what the note was all about. Carson made the drop and the criminal was caught. “He’s got brass balls,” one of the officers said of Carson.

Bushkin, as he does so well throughout the book, finds the romantic-legal resonance in this incident: “When things soured between [Johnny and Joanna],” Bushkin writes, “her gratitude for his unquestioning love for her during this time nonetheless did nothing to keep their marital dispute on a fundamentally respectful plane.” Hence the $35 million.

Carson is not the only one whose marital status was compromised during this time — or, as Bushkin puts it, “I had enjoyed many adventures in Vegas and on the road that did nothing to reinforce marital bonds.” Bushkin and his wife, Judy, were separated and then divorced. His marriage ended, in other words, ended because of his devotion to Carson and to the lifestyle that being in Carson’s entourage afforded him. “And here’s the kicker: because I was alone more, I was available to Johnny more.”

Bushkin made his expanding presence felt by securing Carson a contract worth $25 million a year (or roughly $75 million in today’s values) and ownership of The Tonight Show, which allowed Carson’s production company to reap some $50,000 every week in pure profits. This was in 1980; nobody had ever seen a deal like this bestowed upon an entertainer, and, writes Bushkin, it “has possibly not even been matched, except perhaps many years later by the estimable Oprah Winfrey.”

But Johnny Carson was no Oprah Winfrey, at least as a businessperson. Whatever opportunities for moguldom his status as star producer afforded him went unexploited. Though he had untold potential for entertainment-world dominance at his fingertips, he turned his back on it because he understood that, beyond a certain level of wealth and acclaim, one’s time becomes exponentially more valuable than either. (This understanding was vindicated when, in 2005, Carson died with hundreds of millions still in the bank, most of which went to his charitable trust.) Carson never was acquisitive for acquisition’s own sake, at least when it came to money. “Johnny,” writes Bushkin, “was never remotely cheap. Money was of very little concern to him, and he spread it around liberally.”

Nonetheless, it was Carson’s entrepreneurial apathy that led to his and Bushkin’s final break. Bushkin thought much of expanding Carson Productions far beyond The Tonight Show; Carson did not. Buskin did much of his thinking out loud and behind Carson’s back. He writes here with what seems like contempt, or at the very least exasperation, about Carson’s approach to his abandoned business ventures:

He was free to do literally whatever he wanted. He could ignore a sweet deal from Coca-Cola because he didn’t want to make a lasting commitment. When he didn’t like modeling for photographers for two days a year, he could afford to close down his multimillion-dollar clothing company; when he got tired of playing nightclubs, he bailed on his dates in Las Vegas; when he decided he didn’t like going to see the rushes of movies in production, he closed up his company’s successful movie division; and when he got tired of being the CEO of Carson Productions, he decided to rid himself of the company.

When Carson died, Bushkin refused all the many calls that came in from the news media soliciting comment. Now he has spoken. He says it was a friend’s idea, this book, but one wonders about the ingenuousness of that statement. Although it doesn’t feel like a malicious hit, it certainly feels like something personal and premeditated. That’s part of what makes it so engaging. Bushkin had his reasons for being silent at the time of Carson’s death, and he has his reasons for not being silent now. Back then, he writes, “I couldn’t work up any noble sentiments about the man, and I did not want to look like I was taking a cheap shot.” Now, the cooling-off period over, Bushkin has taken his shot clean.

¤

LARB Contributor

Lary Wallace is an eccentric-at-large and the features editor of Bangkok Post: The Magazine.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Bob Fosse and the Bejeweling of Horror

Fosse is a book celebrating a life, even though, as Sam Wasson writes, Bob Fosse “had the jazzman’s crush on burning out.”

A Novel Life

Middlemarch is, of course, not the only novel that changes with the age of its reader, but it does attract a particular kind of rereading.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!