Here Be Monstrous Architects: On Joshua Comaroff and Ong Ker-Shing’s “Horror in Architecture”

Stephanie Schoellman reviews Joshua Comaroff and Ong Ker-Shing’s “Horror in Architecture: The Reanimated Edition.”

By Stephanie SchoellmanMay 23, 2024

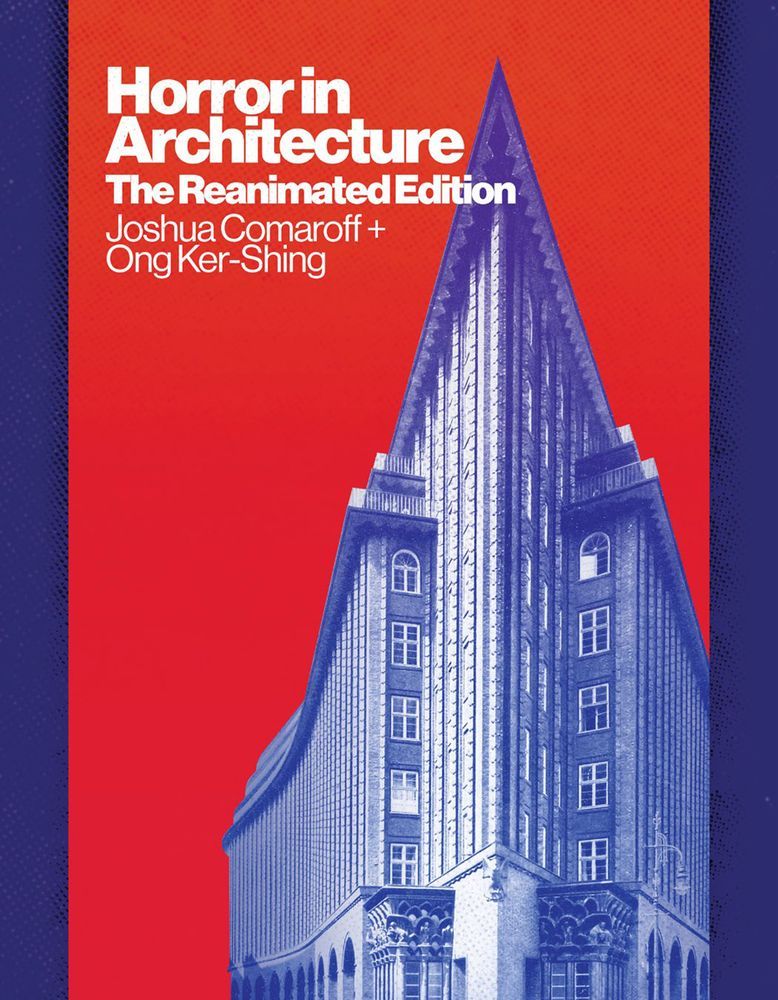

Horror in Architecture: The Reanimated Edition by Joshua Comaroff and Ong Ker-Shing. University of Minnesota Press. 264 pages.

WHILE DRIVING THROUGH a neighborhood that endlessly replicates clone homes or traveling a city where once bustling factories have shuttered their industry, one might wonder who designed these domestic dystopias and apocalyptic sites. In Horror in Architecture: The Reanimated Edition (2024), Joshua Comaroff and Ong Ker-Shing provide an answer: modernity did.

With the grotesque expansion of industry, commerce, and consumerism, the last two centuries have produced hideous progeny. Comaroff and Ker-Shing illuminate the cultural shadows these structural monstrosities cast, shattering illusions of progress by examining the terrors caused by (un)natural innovations—natural in that these innovations “embody processes of genuine consequence,” unnatural in that they are necessitated by the “perverse effects of modernity.”

Through explication and comparison—explaining the exigence and evolution of buildings, then paralleling these histories and features to horror tropes—the authors establish why we should pay attention to these structures: they are spaces whose spatiality is not just made of wood and metal, but also crisis, which is their true cement. The authors insist that the horror such architectures externalize should urgently be considered, for such horror is embedded within our social and economic systems and, if not heeded, in our futures.

Comaroff and Ker-Shing have revised their initial thesis (from the original 2013 text), using responses from critics and experts “to make clear why architecture matters” as well as “how interesting times make interesting buildings.” Because of the intersectional issues (in)forming a building’s construction as well as its reception, the ambitious monograph is interdisciplinary in nature, examining the matrix where materiality, affect, and their makers lurk. For this reason, the book feels a bit like an exquisite corpse itself, entangling a variety of academic theories in purposeful and necessary ways in order to comprehend the complexity of, first, a building’s human-manufactured ontology, and, secondly, its impact on us.

Reading Horror in Architecture a decade after its first publication is particularly compelling. With additional environments rendered freakish by free enterprise rigor, the evidence for Comaroff and Ker-Shing’s observations proliferates in cities and suburbs alike. Reading it as a Gothic scholar who regularly considers how horrific cultural productions instruct us, revealing our anxieties and providing cautionary tales, has transformed how I see human-made environments.

Comaroff and Ker-Shing use horror as the lens through which to view these structures and the language by which to describe them—aptly so, because the conditions that summon their rise (often from the unhallowed grounds of stolen or abused land) are themselves horrific and, importantly, foster yet more horrific conditions. Horror may seem a bit melodramatic until one recalls the hypnotic and numbing flicker of fluorescent lights stacked upon each other in gray corporate skyscrapers, reddening eyes and blocking stars. Or perhaps, more disturbingly, one witnesses news stories featuring the remains of Gaza, consequences of settlement colonialism and global complicity. The horror of those settings lies not in exaggerations but rather, as the book proclaims, in the tangible—and accurate—expression of extremes, for we live in an era of extremes.

As Comaroff and Ker-Shing note, “Horror is one by-product of modernity and thus mimics its advanced forms”; it manifests immoderations and indulgent extravagances. Hence, when we see buildings bloated, deteriorated, mutated, duplicated, or dislocated, often a dereliction of ethics is the remodeling contractor at work. By interpreting buildings in horror mode, the authors unveil the systemic greed, unsustainable growth, and unchecked power embedded in their foundations.

Importantly, the authors remind us that horror is not automatically pejorative. Decay and distortion, as Antonio Rocco proclaimed in 1635, are sites of change and invention. It can be further described as agonizing astonishment; an anti-pastoral; something appalling; an incongruous immensity, “push[ing] against the bounds of the thinkable”; or a physical, even spiritual, violence/stimulation that sublimely overwhelms. While these descriptions seem like undesirable ambiences, they nevertheless conjure strong emotions and, subsequently, novelty.

The purpose of horror is to consciously and viscerally startle us, shocking and awakening the senses that have grown anesthetized. Horror disrupts what has become normalized, wrecks the romanticized, and interjects when refinement is too docile and demure to object. As Comaroff and Ker-Shing state: “Deviance teaches; charm will make you sick.” If horror is not superfluous for the sake of being superfluous—if it is a symptom, a harbinger, a way to recognize the “ache of an increasingly disenchanted world […] groping for intensity of experience,” as the authors claim—then these sites are where the “dynamism of the modern is especially legible,” and if we are wise, we should let them educate us.

To receive this education, Comaroff and Ker-Shing invite us to search for the source of a built environment’s deviance in order to learn more about the circumstances, intentional and otherwise, that brought it into being. “Deviant buildings,” as they delightfully call them, are not what I was picturing when first reading the phrase. I imagined an anthropomorphic house with murky second-story windows, squinting curtain-lids, and a grimacing mouth of a door, its frown casting an insidious mood throughout suburbia. Contrarily, “deviant buildings” are not simply personifications of sordid histories or haunted in the standard sense. Instead, Comaroff and Ker-Shing suggest that “deviant buildings” signal “the birth and death of conventions,” providing teachable moments.

In the classroom, I use terrifying narrative texts as teachable moments, asking my students to interrogate the root causes of the terror. They have to research and analyze the context of the story, divining the fears of the authors, characters, and readers and speculating from where they might hail. Horror in Architecture asks us to consider the same: Who/what is the source of the horror? Who/what sustains it? How does it function? By reading and viewing buildings much the same way we read and view media, specifically horror media, we are able to track down what triggered their presence. Comaroff and Ker-Shing ominously allege that this line of inquiry is needed because these forms “are highly suggestive in considering possible futures”; they are trajectory maps for the development or devolution of communities.

One of the many examples the authors give is the American commercial renaissance of 1840–1929, when mammoth buildings were needed in massive quantities. The resulting “enlargement (and the involution) of new buildings expressed the evolution of commercial institutions in general.” The result was obscene ingenuity—obscene because of the sheer scope and scale, ingenious because the colossal challenge was matched with colossal constructions. But, as Comaroff and Ker-Shing point out, “This is not merely the quandary of a certain moment of American architectural development. Quite the contrary.” “Horror,” they argue, “is an ever-present and radically protean effect” and “a chronic symptom of modernity’s violent and cyclical dynamism, its expansions and convulsions and metamorphoses. For this reason, unease remains endemic in the built environment.” The obscene ingenuity spawns in kind. Thus, the horrors persist; so must our inspection and, hopefully, intervention.

While the authors’ prose insightfully analogizes architectural features with horror images and themes in literature and popular culture, the sections that pair visuals are especially elucidating. For example, when divulging the horrors of conjoined doubles, a film still of Ash from Sam Raimi’s Army of Darkness (1992) sprouting an evil twin from his body is juxtaposed with pictures of several buildings: Johnston Marklee’s House House (2008) in the Chinese city of Ordos, Inner Mongolia, and Alejandro Aravena’s Siamese Towers (2003) at Universidad Católica de Chile, San Joaquín. Both emulate the image of Ash in the throes of self-cloning with their dual gables and columns that resemble each other but which are also slightly askew, as if they are trying to separate from the host. Together they exhibit the tensions between being apart and a part of a whole. Their struggle between autonomy and assimilation embodies “a resistance to resolution”—a staple in horror narratives.

By amplifying the composition of these abodes and viewing them through the lens of horror, the authors’ framing excavates the ideologies hiding beneath their floorboards and walled up in the same spaces we indwell. As Comaroff and Ker-Shing admonish: “A building’s organization, size, typological articulation, and varied semantic expressions all reflect the designer’s attempt to reconcile forces that exist—in a profound sense—prior to or beyond the ‘scope’ of that individual’s contribution.” Moreover, the Chartered Institute of Building (CIOB) provides a construction-specific definition for context, which serves as a metaphor for how these buildings operate as microcosms. The CIOB-supported construction resource Designing Buildings outlines that view of “context”: “The buildings and structures that make up the built environment do not exist in isolation but are conceived and designed in order to respond to, support, and enhance their surroundings […] linking new and old.” Or, as Comaroff and Ker-Shing would assert, horrific connotations have the potential to subversively call out, counter, and alter epistemes, “not a critique through design, as has been made in the dominant schools of thought, but a deeper rejection of the assumptions and social requirements on which those schools are based.”

With its synthesis of theories and philosophies, Horror in Architecture will be useful across disciplines and curricula, creating a dialogue that breaks down compartmentalized, scholarly walls and opens a space to evaluate the intersectional crossbeams that shelter and cage us. However, the most resonant part of the authors’ assertions is in the resin—the implicit ethics that Comaroff and Ker-Shing’s research and analysis ask: Who are the architects of these monstrosities? And what are their (our) responsibilities?

These horrific living environments are built by economies that are, in turn, built by subjectivities (who are also themselves built by these economies) of the privileged and of the exploited alike. Inevitably, architecture’s impression is not just on a landscape and its inhabitants of a particular time and place; it also extends to our social imaginations—how we live and interact communally, how we are corralled into certain movements, and even how we identify nationally and culturally. These blueprints are the plot plans of posterity.

Horror in Architecture has caused me to look at buildings as sentient entities. Whether in the shadow of an edifice or its bowels, I cannot help but introspect the exteriors and recesses, wondering what legion of forces animated their design and, ergo, what designs they are animating within us.

LARB Contributor

Stephanie Schoellman, PhD, is an assistant professor of instruction in the English department at the University of Texas at San Antonio. Her scholarship focuses on the Gothic imagination, popular culture, and decolonial theory. Forthcoming work includes a book chapter about final girls in Heroic Girls as Figures of Resistance and Futurity in Popular Culture (Routledge, 2024), an article on Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s Mexican Gothic in Gothic Nature Journal, and a book chapter on Egyptomania and millennial nostalgia in the film The Mummy (1999) for The Mummy Edited Collection.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Contours of Negative Space: On Tessa Hulls’s “Feeding Ghosts”

Martin Dolan reviews Tessa Hulls’s “Feeding Ghosts.”

Haunting Objects: On the Work of Darrel Ellis

Jonathan Alexander considers the work of Black, queer photographer Darrel Ellis, whose work is receiving renewed attention.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!