Give and Go: The Double Movement of Shut Up and Dribble

Samantha N. Sheppard thinks about the back and forth between social injustice, social progress, and the institutional power of the NBA in Showtime's Shut Up and Dribble.

By Samantha N. SheppardFebruary 12, 2019

How would you respond if a conservative media pundit told you to “shut up and dribble” on national television because you criticized the president? If you are LeBron James, a basketball superstar and media mogul with his own production company, you fund a documentary series that traces how basketball players have sparked sporting and social change over the last six decades. And you ironically title it after the insulting command.

With SpringHill Entertainment, James and his long-time business partner Maverick Carter have created a range of fiction and nonfiction television programming and feature films that tackle sporting and non-sporting subjects. They have produced unscripted works such as YouTube Original’s Best Shot (2018-present) and Starz’s Warriors of Liberty City (2018-present) and scripted series such as Starz’s Survivor’s Remorse (2014-2017). They are also developing new projects, including a limited series on Madame C.J. Walker for Netflix starring Academy Award winner Octavia Spencer and the highly anticipated Space Jam sequel starring James himself. Shut Up and Dribble comes on the heels of SpringHill Entertainment’s HBO documentary, Student Athlete (2018), about the exploitation of college players by the NCAA. Directed by Gotham Chopra, Shut Up and Dribble premiered on Showtime in November 2018 and is a three-part docuseries that chronicles the world-historical impact Black players in the NBA have as athletes, activists, businessmen, commentators and community representatives on and off the court.

Featuring a highlight reel of NBA game changers in terms civil rights issues, Shut Up and Dribble is also about the changing power dynamics within the league today. As narrator, sports journalist Jemele Hill explains, “in America, Black athletes are supposed to be the talent and not the power brokers.” The actions of the players discussed in the docuseries, some of whom paid dearly for their dissent, underscores how racial power is challenged and maintained by athletes and the league alike. Shut Up and Dribble is a valuable contribution to the sports documentary landscape, one that protests the deracinated and apolitical histories of the league. However, the “give and go,” or, put differently, the back and forth narrative of social injustice and social progress works overtime in the docuseries. Shut Up and Dribble attempts to critique the NBA and American society’s injustices while celebrating the league through a linear narrative of progressivism, creating a revelatory but not revolutionary counternarrative about the professional sport’s impact beyond the arena.

In “Notes on Deconstructing the Popular,” Stuart Hall explains that popular culture should be understood as the struggle between dominant and subordinate groups for social order. Hall describes these forces as “the double movement of containment and resistance,” a dialectic that gets at the sporting-society intertext discussed in the series. Shut Up and Dribble details, for instance, how Oscar Robertson, as president of the Players Association, sued the NBA and lobbied for “free agency;” challenging the status quo, disrupting the entrenched player-owner-association power dynamic, and changing the rules of the game. The series directly engages the rivalry between athletes and the NBA for power and influence on the league and its fans. However, in relying on footage from NBA games and attempting an unbiased, journalistic tone, the docuseries reifies and at times capitulates to the NBA’s centrality, economic hold, and official authority in all things basketball. Every critique doubles as a celebration.

Part One considers the early history of Black athletes in the league, telescoping in on the paradigm-shifting innovators like Bill Russell, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Oscar Robertson, and Julius “Dr. J” Irving, among others. Curiously, the episode does not mention Black pioneers Chuck Cooper, Harold Hunter, Nathaniel “Sweetwater” Clifton, or Earl Lloyd, who were the first African Americans to be drafted, under contract, signed, and/or play in the NBA. Overall, the series unpacks the stories behind key figures such as Russell, the Hall of Fame player and first Black coach in the league, explosive moments like the Malice at the Palace melee, the media spectacle and racial subtext of the Magic Johnson and Larry Bird rivalry, and the changing demographics of the league.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s (then known as Lew Alcindor) story stands out in Part One. His dominance on the court and in the political arena, made him a towering figure even apart from his 7’ 2” frame. As the episode explains, in 1967 the NCAA banned dunking in intercollegiate men’s basketball, a prohibition popularly referred to as the “Alcindor Rule.” And so Abdul-Jabbar perfected the “sky hook,” a much harder shot to defend against than the dunk. Despite the way the NCAA tried to contain and discipline Abdul-Jabbar’s play, his transformative athleticism became his mode of resistance. His actions of the court, refusal to participate in the 1968 Olympic Games to protest racism, conversion to Islam, political engagement, and print and televised journalism continues to place him within the lineage of black sports figures as public intellectuals, media critics, iconic community leaders and engaged citizens.

Part Two focuses on the Michael Jordan era when many athletes increased their wealth, global celebrity, and post-athletic prominence by entering into sponsorship deals with fashion and sports beverage brands. This episode provides a resistant counternarrative to Jordan’s deracialized hypercapitalism through a focus on the actions of Craig Hodges and Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf. Hodges, Jordan’s former Chicago Bulls teammate, wore a dashiki and kufi to the White House during the Bulls championship celebration visit and slipped President Bush a letter explaining why he should care more about the poor and people of color. Abdul-Rauf, former star of the Denver Nuggets, refused to come out of the lockers to stand for the national anthem, calling the flag a symbol of oppression. Both Hodges and Abdul-Raouf were blackballed from the league (which coaches and league officials deny in the documentary) and could be written off as “cautionary tales.” However, Shut Up and Dribble recasts these players as the unsung heroes of an NBA era often wrongly remembered as apolitical. The league is revealed to be deeply invested in forgetting these oppositional and subversive acts; to remember them is to be reminded that the institution itself has (and will) continually run afoul of Black athletes struggles for autonomy and critiques of the system on and off the court.

The NBA is invested in containing Black players and their social critique while emphasizing charitable acts that leave power unchallenged. Part Three demonstrates this fact through detailing the suspension of Ron Artest (currently Metta World Peace) after attacking Detroit Pistons fans who threw beer on him while he lay on the scorer’s table. This event reinvigorated the fear that the league had gotten too Black and too out of control; rehabilitation and discipline were formulated in a three-piece suit and tie-dress code, a move to whiten and conservatively reform the league post-Allen Iverson. As former NBA commissioner David Stern explains: “We set down the rules, and our players not only conformed. They went over the top.” The scene cuts to James in a blazer and button-down shirt as Hill narrates that “not all players saw the dress code as a personal attack. The NBA’s newest generation was stepping out in different threads, inspired by a hip-hop culture that was ready to grow up.” James, who becomes the subject of the rest of the episode, becomes complicit in the NBA’s dominant narrative of control.

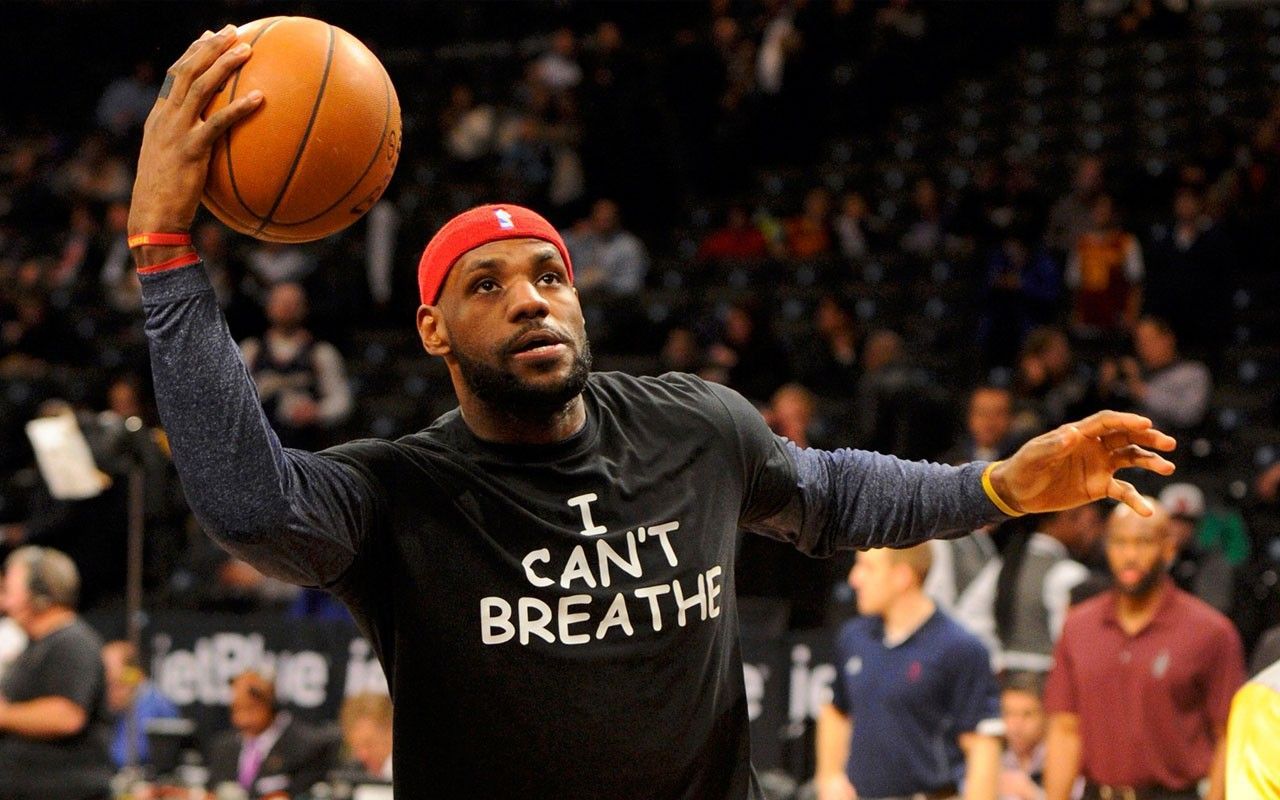

While the episode begins with this issue, Part Three is mostly dedicated to contemporary athletes’ actions during the Black Lives Matter movement. The episode shows the Los Angeles Clippers players repudiating their racist former owner Donald Sterling by taking off their Clippers gear before a game in protest. The murders of Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, and many other Black men and women inspired nationwide collective acts of riot, protest and solidarity. James’ Miami Heat team donned hoodies in protest of the vilification of Martin in the media and a range of players, following Derrick Rose, wore shirts that read “I Can’t Breathe” following the brutal killing of Garner by the NYPD. They were not reprimanded by the league officially, but commissioner Adam Silver explained: “I respect Derrick Rose and all of our players for voicing their personal views on important issues, but my preference would be for players to abide by our on-court attire rules.” James and fellow NBA players’ sartorial statements are meant to cast him and others within the lineage of past ballers who stood up and spoke out against sporting and social injustice, reshaping the league and criticizing the society which celebrated and scorned them. In the end, Shut Up and Dribble’s critiques of the league and society is a story of triumph, with sporting and social progress superficially embraced by a league where Black lives matter only in relation to the economic bottom line. In other words, while the players protested, they also still played; everyone still got paid.

I remain unconvinced by the series’ optimistic rendition of the NBA’s progressivism even as it tries to cement the league’s past and present cultural relevancy. The fact that the docuseries relies on so many institutional voices from within league, including former and current players and commissioners such as David Stern and Adam Silver shapes the boundaries of possible critique. There is a “past-tense” portrayal of the league’s conservatism, which makes LeBron James’ outspoken actions during press conferences and in producing this docuseries fitting for the league’s newfound pro-athlete/activist stance. Activism that does not disrupt the order of things, particularly the ties between capital and power, are symbolically loaded and powerful but bereft of any material significance or impact.

Shut Up and Dribble narrates a story of individual and collective Black male resistance within the confining strictures of white corporate control and capital profit. In doing so, Shut Up and Dribble tells well-worn and popular stories of social change, ignoring and omitting histories, narratives, and figures that disrupt a monolithic and masculinist frame of social change. Figures such as the queerly perverse and infamous Dennis Rodman are mostly ignored, and Magic’s activism and business achievements after his HIV reveal are not mentioned. And most importantly, women’s voices are heard but carry no authorial weight despite Hill’s rather thin narration, which she wrote herself. Women are all but absent from the series besides sportswriters Jackie MacMullan and Ramona Shelburne. Where are the Black feminist writers/critics whose works impact Black baller discourse? Where are the WNBA stars? Is there room for, hell, even a “Basketball wife?” If there is room for Justin Timberlake, Larry Wilmore, Jay-Z, Kendrick Lamar, and a host of pop culture figures to be talking heads, is there not space for Cheryl Miller, Lisa Leslie, Candace Parker, Diana Taurasi, bell hooks, Shaunie O’ Neal and others to discuss this critical history and its impact on them. The WNBA’s history is intertwined with the NBA’s history. And yet, the WNBA is never mentioned explicitly, only an image of the players donning protest t-shirts is shown for mere seconds. While the final episode shows current players taking a stand with their hoodies and t-shirts, WNBA players were the first to do this and other collective measures, including media blackouts where they refused to talk about anything except for racial injustice and violence against people of color.

My main issue with Shut Up and Dribble’s retrograde omission of women from the current athletic and sociopolitical moment is that it unnecessarily reproduces a masculinist sporting narrative about social change and reifies the sport’s cultural relevancy to and for men only. Have we not learned from activist and sociologist Harry Edwards, who in the 50

th

anniversary edition of The Revolt of the Black Athlete, explains that “there is one glaring omission that must be addressed: the lack of due attention paid to the status, circumstances, outcomes, and contributions of Black women—either as athletes or in the struggles for change more generally.” While it could be argued that Shut Up and Dribble is about the NBA, a male league, the film easily pivots to discuss the broader sports landscape and social issues, including the actions of non-basketball players including sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos, boxer Muhammad Ali, and football quarterback Colin Kaepernick. Black women can not only dribble, they can also critique the NBA’s social control and power dynamics. It is time for docuseries like Shut Up and Dribble to not only pass the ball but also the mic because women are done being silent.

¤

LARB Contributor

Samantha N. Sheppard is the Mary Armstrong Meduski '80 Assistant Professor of Cinema and Media Studies in the Department of Performing & Media Arts at Cornell University. She writes extensively on black cultural production and production cultures. She is the co-editor of From Madea to Media Mogul: Theorizing Tyler Perry and has a forthcoming manuscript titled Sporting Blackness: Race, Embodiment, and Critical Muscle Memory On Screen, which is under contract with the University of California Press.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The LARB Ball NBA Roundtable

On the inevitability of professional basketball

The LARB Ball NFL Roundtable

On brain trauma, Budweiser, Steamin' Willie Beamen, and the blurring of Colin Kaepernick's dissent.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!