IT IS IMPOSSIBLE to discuss British author Ted Lewis’s 1970 novel, Jack’s Return Home, without mentioning its better-known 1971 film adaptation, Get Carter. Rarely has such an influential crime novel dwelt so deeply in the shadow of its cinematic adaptation. In the wake of the movie’s success, the book was quickly retitled Get Carter (which is how I’ll refer to it) and the main character forever associated with British actor Michael Caine, then at the height of his preternaturally long acting career, in a snappy suit and tie, grimly looking over the barrel of a shotgun.

Not that anything else Lewis wrote was particularly successful. As British crime writer Ray Banks observed in a piece on the site The Rap Sheet: “As far as forgotten books go, you could make a claim for pretty much anything Ted Lewis wrote.” But what Lewis lacked in sales, his books, particularly Get Carter, made up for in the glowing praise of crime writers, nearly all of it posthumous.

Get Carter and its subsequent prequels, Jack Carter’s Law (1974) and Jack Carter and the Mafia Pigeon (1977), have recently been rereleased by Syndicate Books, which marks the first time they have been available in North America for 40 years. The blurbs at the beginning of the new versions represent a who’s who of muscular crime fiction: Dennis Lehane, David Peace, Derek Raymond, James Sallis, Stuart Neville, and John Williams. Williams, author of The Cardiff Trilogy, describes Get Carter as “the finest English crime novel ever written.” Raymond and Peace credit him not only with influencing their work but also with kick-starting noir fiction in the UK.

Lewis, who trained as a commercial artist and wrote for television (his Doctor Who scripts were deemed too dark for the show’s prime-time slot and never used), went from the success of Get Carter, his second book, to a poorly paying job drawing postcards for a local council within the space of a few years. He died at the early age of 42, largely due to ill health associated with rampant alcoholism. He left a legacy of nine novels, most of which with the exception of Get Carter have remained out of print. Syndicate Books is planning to rerelease all of them.

Get Carter is set in 1970 and focuses on an enforcer for a criminal organization, or “firm,” run by two brothers, Gerald and Les Fletcher. Carter leaves “the smoke,” a.k.a. London, and travels back to the unnamed working-class industrial town in northern England he grew up in to investigate the death of his estranged brother, Frank. Drunk on whisky, Frank ran his car off a cliff. Given his brother was relatively clean-living and never touched hard liquor, Carter is suspicious. As he speculates at the beginning of the book: “They hadn’t even bothered to be careful; they hadn’t even bothered to be clever.”

“They,” the organization that runs the town’s criminal activities, becomes the focus of Carter’s considerable destructive capabilities as he attempts to find out who and what led to his brother’s death. A particular target of his attention is Eric Paice, an enemy from his youth, who now works for local crime lord Cyril Kinnear. Other notable characters include Frank’s mistress, Margaret, and his brother’s teenage daughter, Doreen. Doreen and Margaret know more about Frank’s demise than they let on. It is also clearly implied that Doreen is actually Carter’s daughter, the result of a drunken fling with Frank’s then-wife. The fling is just one possible reason for the two brother’s estrangement. Carter’s memories of their youth together, the fact that Frank was law-abiding whereas Jack was destined from an early age to pursue the criminal life, and the conflicting emotions this creates in Jack’s mind all add dramatic pathos to the story.

Jack Carter’s Law appeared in 1974. Much of it is set in Soho, then the cosmopolitan vice capital of London and the center of the Fletchers’ criminal organization. It is Christmas Eve, and Carter is busy trying to track down a “grass,” or informant, who has information that could put the Fletchers in jail. As is the case in Get Carter, Carter is carrying on an affair with Audrey, the wife of Gerald Fletcher. Audrey and Carter are plotting how they can get as much of the brothers’ money as possible and escape England to somewhere warm. Carter would welcome the opportunity to have Gerald and Les in jail were it not for the fact that the informant could implicate him and half the Fletchers’ organization in criminal activities. Adding to the pressure to locate the informant, rival firms are keen to use the situation to advance their own criminal ends. Without warning, Gerald and Les decamp for the safety of their Majorcan villa, leaving Carter to sort out the mess.

Jack Carter and the Mafia Pigeon, the second prequel, was published in 1977. Business for the firm is good. So good, Gerald and Les want to show their appreciation to their chief enforcer by sending him on a holiday to Spain. Unbeknownst to Carter, the Fletchers’ secluded villa is already occupied by a cowardly house steward, Wally, and a psychotic American gangster turned mafia informant on the run from his former colleagues. Carter is pissed off because he thinks his bosses have sent him under false pretenses to safeguard the mafia informant. But the Fletchers have a far darker task in mind. The situation becomes even more complicated by the appearance of Wally’s daughter, a precocious, sexually assertive 17-year-old, who has quit art school and fancies a cheap holiday in Spain.

Understandably, both prequels have the air of being written to cash in on the success of the first Jack Carter novel and the subsequent movie, and feel particularly influenced by Caine’s role as Carter. Did Lewis write the prequels with Caine’s performance in mind? Or having seen it, can we not help but envisage him as Carter? The answer is most likely both.

Obviously, Carter is younger in the prequels, and there is more of a laddish swagger to him. While Jack Carter’s Law in particular is full of descriptors of swinging London, all the Tretchikoff prints, sunken lounge rooms, and modern Swedish furniture can’t hide Jack’s air of unsophisticated working-class Englishness. Apart from having sex with Audrey, he seems most happy with a cup of tea and a copy of the Daily Express. He hates leaving the familiar surrounds of London, and in Jack Carter and the Mafia Pigeon is reluctant to travel even to Spain, never having flown before. The prequels also contain a strain of black humor, something almost totally absent in Get Carter. None of this is to suggest the prequels aren’t worth reading, but they’re nowhere as good as the first book. To be fair, given the effusive praise for Get Carter mentioned earlier, how could they be?

Lewis had a masterful ability to convey place. Take, for example, this passage from Get Carter:

We were in the middle of a dozen blocks of tall council flats. They looked greyer than the day. We walked across a dull wet patch of grass and under one of the blocks, and turned left. There was a lift, one of those aluminium-finish things that always smell of piss. We got in. She pressed Four on the panel. She pushed her hands in to the pockets of her short artificial-fur coat and leaned back against the wall and looked at me. The door rattled shut and the lift moved. I threw my cigarette on the floor; the stink didn’t improve the flavour. The girl kept looking at me.

Or this description earlier of a bar opening and its sad patrons in Jack Carter’s Law:

In the bar there is the usual after 11 A.M. crowd; the swell of drinkers who are all steamed and pressed and smelling of aftershave, and except for the runniness around the rims of their eyes you’d never guess that they’d had to pour themselves a sherry before they could get out of bed and most of them will have spent an hour shaking on the toilet (or over it) before restoring some kind of humanity to their bodies.

But there’s no shortage of crime writers who can craft a good sentence. The reasons for Get Carter’s ongoing influence run deeper. As Mike Hodges, who directed the movie, writes in an introduction to the Syndicate Books rerelease: “It [the book] arrived in the post, out of the blue, along with an offer to write and direct it. Its literary style was as enigmatic as the manner of its arrival. Whilst set in England and written by an Englishman it was (aside from the rain) atypically English.” The setting, the grimy industrial North, was different from that of most English crime fiction. The plot and feel had more in common with hard-boiled noir American film and fiction. Indeed, in an epilogue to the third book, author Nick Triplow, who is researching Lewis’s biography, writes about how Lewis was a major fan of Lee Marvin, the personification of hard-boiled ’60s masculine cool. Marvin’s performance in John Boorman’s 1967 movie Point Blank feels as if it was a particularly prominent influence in Lewis’s work.

Carter’s character was another major departure. He is cunning, violent, ruthless, with an unfailing eye for human weakness, willing to use and sacrifice anyone to get what he wants. Cuckolding one of his bosses while scheming to steal as much of their money as possible is only the most obvious example of his depravity. Even Doreen, possibly his own daughter, is not completely safe from his predatory instincts. “She was older than her fifteen natural years,” he thinks to himself at one point in Get Carter. “I could have fancied her myself if she hadn’t been who she was. You could tell she knew what was what. It’s all in the eyes.” The books are full of chilling observations like this. The first-person narration and Carter’s cold-blooded telling and decoding of events create a sense of claustrophobia that conveys both the main character’s emotional memory and his mixed feelings toward Frank.

The strongest aspect of Get Carter is Lewis’s surgical analysis of the political economy of organized crime. “On the surface it was a dead town. The kind of place not to be left in on a Sunday afternoon,” is how Carter first describes his hometown. He continues:

But it had its levels. Choose a level, present the right credentials and the town was just as good as anywhere else. Or as bad. And there was money. And it was spread all over because of the steelworks. Council houses with a father and a mother and a son and a daughter all working. Maybe eighty quid a week coming in. A good place to operate if you were a governor who owned a lot of small time set-ups. The small time stuff took the money from the council houses. And there were a lot of council houses. Once I’d scrawled for a betting shop on Priory Hill. Christ, I’d thought, when I’d happened to find out how much they took in a week. Give me a string of those places and you could keep Chelsea. And Kensington. If the overheads were anything like related to what that tight bastard I’d been working for was paying me.

Get Carter successfully transplanted a central trope of American noir fiction and film to England: the corrupt, crime-infested urban space and the alienated stranger whose motives lead him to inhabit it and to get into direct conflict with those who control it. The anonymous industrial town of Carter’s youth is similar to Personville, or “Poisonville,” as the locals describe it in Dashiell Hammett’s 1929 classic, Red Harvest. Hammett’s description of Personville could apply word for word to the setting of Get Carter:

The city wasn’t pretty. Most of the builders had gone in for gaudiness. Maybe they had been successful at first. Since then the smelters whose bricks stacks stuck up tall against a gloomy mountain to the south had yellow-smoked everything into uniform dinginess. The result was an ugly city for forty thousand people.

Carter’s hometown is one in which criminal elements hold sway; the police are completely absent in Get Carter. Carter’s whole reason for revisiting the town he grew up in, a place he loathes, is to investigate his brother’s death, something the authorities have failed to do. The only evidence of law enforcement in any of the Carter books occurs in Jack Carter’s Law: a corrupt cop, one of many on the Fletchers’ payroll.

Get Carter also captures the social changes underway in Britain as the 1960s came to an end. As Hodges writes: “Britain in the ’60s was, for some of us, a hopeful and exciting time when radical ideological dreams seemed realizable. We were fooling ourselves. The fault line of class and privilege fracturing British society […] proved impossible to breach. By the time Ted’s book was published those delusional dreams had evaporated.”

Lewis had a shrewd eye for the shifting class politics of late-’60s England, the point at which the austerity of the postwar years had melted away and prosperity was slowly creeping into the regions, creating a new middle class. Carter’s efforts to discover what happened to his brother involve him having to navigate the class politics of his hometown. His investigation begins in working class pubs and bedsits, the familiar haunts of his youth. But the closer he gets to the people who run the town’s illegal activities, the people who can tell him what happened, the more contact he has with its upper classes.

This is demonstrated when Carter follows Paice to the casino run by Paice’s employer, Kinnear. As Carter enters the casino, he quickly analyzes the clientele, farmers, owners of chains of cafés, contractors, builders, “the new gentry,” as he calls them.

I looked around the room and saw the wives of the new Gentry. Not one of them was not overdressed. Not one of them looked as though they were not sick to their stomachs with jealousy of someone or something. They’d had nothing when they were younger, since the war they’d gradually got a lot, and the change had been so surprising they could never stop wanting, never be satisfied.

The Fletchers are obviously based on the real-life Kray brothers, Ronald and Reginald, powerful gangsters who ruled London’s East End through a combination of robbery, arson, protection rackets, and murder, before finally being arrested, tried, and convicted, with great media fanfare, in 1969. Lewis portrays them as thoroughly nouveau riche. “Gerald in his country hounds tooth and his lilac shirt, sitting at his Cintura-topped desk, the picture window behind him […] and Les sitting on the edge of the desk, in his corduroy suit, thumbing through a copy of Punch.” Carter, meanwhile, is more akin to a hungry entrepreneur of the type that would thrive as Britain progressed through the 1970s up to the election of the fiercely conservative Thatcher government in 1979. His politics are in sync with the hard right: his sexism and casual homophobia, his description of foreigners as “wogs,” the disdain with which he describes his brother Frank’s ex-wife and her leaving him for a Pakistani immigrant.

Get Carter was made because film producer Michael Klinger was looking for a vehicle to capitalize on the immense interest generated by the Kray brothers’ trial. With the exception of two Roman Polanski films — Repulsion in 1965 (for which he was uncredited) and Cul-De-Sac (1966) — his CV mainly consisted of youth exploitation movies capitalizing on the sexual hijinks of Swinging Sixties London, with titles such as Primitive London (1965) and The Penthouse (1967). Klinger bought the rights to Jack’s Return Home and chose Mike Hodges, who until then had only worked in TV, to bring it to the screen.

Hodges, who also wrote the script, kept the narrative spine of Lewis’s book and much of the dialogue, but jettisoned most of Carter’s backstory and changed other key elements of the novel. The town with no name became the fading industrial center of Newcastle (or Newcastle Upon Tyne, as it is now known). Carter’s potential relationship with Doreen is only hinted at. Most radically, whereas Carter’s fate in the book remains inconclusive, in the film he dies, killed by a hit man, presumably dispatched by the Fletchers, whom we glimpse traveling in the same train carriage as Carter in the film’s opening scenes.

If anything, the film is even more hard-boiled and bleak than the book, as Hodges infused it with his experience as a conscript in the Royal Navy in the late 1950s. He spent two years aboard minesweepers, regularly docking at gritty port towns in the North, where he witnessed a side of life he didn’t know existed. The experience blasted away his secure middle-class outlook. As he puts it in his forward: “The poverty and depravation I witnessed in those hell holes blew the scales off my bourgeois eyes forever. From now on I would be no stranger to the sleazy milieu Ted’s novels occupied.”

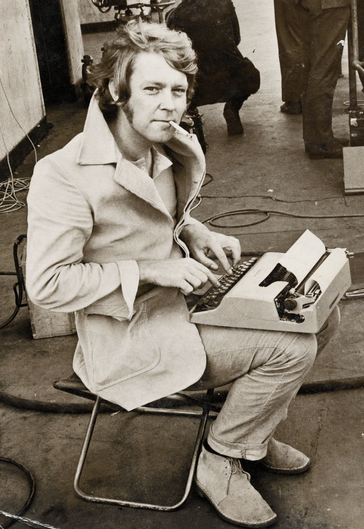

Get Carter was a lean, economical film, shot in 40 days at a total cost of 750,000 US dollars. What the film doesn’t owe to Lewis’s book is made up by the presence and star power of Caine as Carter. “I researched [the role] very thoroughly,’”Caine noted.

I know a few gangsters and I talked to them about the sort of man he is. You find actors often know gangsters — maybe they have a lot in common, when you think about it. Jack Carter is based on someone I know — dress, attitude, frame of mind, talk — even the walk.

Although the movie received a lukewarm critical reaction upon release, it is now viewed as having had the equivalent impact on cinema that Lewis’s book had on crime literature. The fact that Get Carter was not set in London but in a heavily working-class regional area was indeed unusual. Much like Lewis’s novel, it also addressed the end of one decade and the beginning of another, a much harder and far less optimistic period, with all the associated changes in mood and style. The gangsters in Get Carter carry firearms. The violence is more frequent and more visceral. A number of scenes in the film, for example when Jack throws a businessman from the Gateshead car park (demolished a few years ago), still have the capacity to shock.

A more sober assessment is that, while it is an important film, Get Carter represented a shift rather than a radical break with the conventions of British crime cinema. Starting with Richard Attenborough’s turn as the vicious hoodlum Pinkie Brown in the 1947 adaptation of Graham Greene’s 1938 novel Brighton Rock, postwar British cinema produced a body of solid noir cinema: Joseph Losey’s film The Criminal (1960, otherwise known as Concrete Jungle), a gritty story of a man (Stanley Baker) serving a prison sentence for a racetrack robbery who is subject to intense pressure to disclose where he has hidden the proceeds; Cy Endfield’s Hell Drivers (1957), about a truck driver’s efforts to expose the corruption of the company he works for; Val Guest’s Hell Is a City (1960), shot partly in Manchester; Peter Yates’s ultra hard-boiled 1967 dramatization of the Great Train Robbery, Robbery. Even some of the caper films produced during this time, such as The League of Gentlemen (1960), provide a hard kick and a sharp satirical take on England’s all-pervasive class system.

That’s not to say the fingerprints of Get Carter aren’t visible on numerous British films that followed, including Michael Apted’s underrated The Squeeze (1977), The Long Good Friday (1980), and The Hit (1984). It has also been credited as a key influence behind the popular British television crime show The Sweeney (1974–’78), which starred two police detectives called Jack Reagan and George Carter, both of whom had a tendency to break rules.

In terms of broader cultural ripples, MGM commissioned director George Armitage to give Get Carter a Blaxploitation make-over. The resulting 1972 movie, Hit Man, involved a man who travels to Southern California for the funeral of his brother and becomes obsessed with tracking down the individuals responsible for his death. Get Carter was also unremarkably remade in 2000 starring Sylvester Stallone.

With the possible exception of his 1998 film Croupier, Hodges would never again do anything as good as Get Carter. That it has enjoyed a second lease on life as a cult hit is largely due to the co-option of UK ’60s gangster chic by the “Cool Britannia” movement in the 1990s. The best-known manifestation of this is Guy Ritchie’s 1998 film Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels. Ritchie’s film spawned a legion of mostly forgettable movies, all mimicking the style and cadence of Britain’s 1960s underworld.

The most bizarre example of gangster chic was a CD released in 1999, Products of The Environment, that featured notable underworld figures from the 1960s, including former associates of the Krays and Great Train Robber Tom Wisbey, doing spoken word to the music of British rapper Tricky. Just like Jack Carter, Britain’s 1960s criminals were always alert to a new opportunity to extend their influence and make a few quid.

¤

Andrew Nette is a Melbourne crime writer and reviewer. His first novel, Ghost Money, was published in 2012. His online home is www.pulpcurry.com.

LARB Contributor

Andrew Nette is a Melbourne crime writer and reviewer. His short fiction has appeared in a number of print and online publications. His first novel, Ghost Money, was published in 2012. He is co-editor of Beat Girls, Love Tribes and Real Cool Cats: Pulp Fiction and Youth Culture, 1950 - 1980, forthcoming from Verse Chorus Press in 2015. His online home is www.pulpcurry.com. You can find him on Twitter at @Pulpcurry.

LARB Staff Recommendations

On John le Carré’s A Most Wanted Man, from Novel to Film

Contributor Matthew Wolfson on John le Carré’s "A Most Wanted Man"

Gilding the Small Screen: or, “Is it just me or did TV get good all of a sudden?”

The true reasons for TV’s emergence as the preeminent mass medium of the early 21st century are primarily external to the actual business of creating...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!