This piece will appear in the upcoming LARB Quarterly Journal, No. 15: Revolution, available in July.

Become a member today to receive the issue.

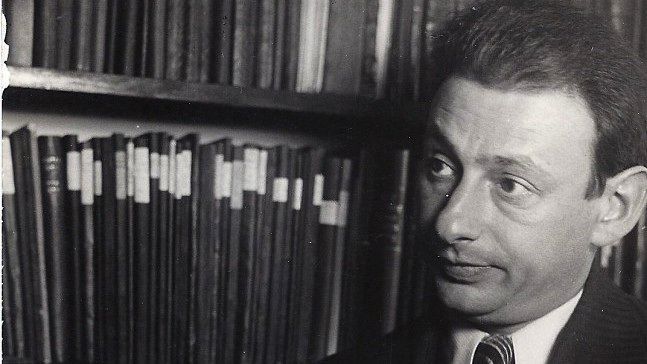

WHEN GERSHOM SCHOLEM, the humanist scholar of Jewish mysticism, first met the philosopher Hannah Arendt in the 1930s he was bowled over by her intelligence and delighted by her character. To Walter Benjamin, he wrote excitedly that Arendt was rumored to have been Martin Heidegger’s most brilliant student. To another friend, he described Arendt as “a wonderful woman and an extraordinary Zionist.” He was moved by her work as director of the Paris office of Youth Aliyah, which helped refugee Jewish children from all over Europe get to Palestine. The fact that Benjamin — Scholem’s intellectual idol, the man he would later say taught him what “thinking really means” through his own “living example” — came to value Arendt’s writing and conversation imbued her with a special aura of intellectual gravitas.

The three spent time together in Paris in 1938 when Scholem was en route from Jerusalem to the United States to deliver the lectures that would become his breakthrough work of scholarship, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism. Scholem, then 41 years old, and Arendt, nine years his junior, held long conversations about Benjamin’s genius, in which Scholem took note approvingly of her aversion to the historical materialists Benjamin associated with at Max Horkheimer’s Institute for Social Research. The pair of them, Scholem resolved, were kindred Jewish spirits with a metaphysical bent. They understood the transcendent implications of Benjamin’s identification of critics with alchemists, probing the enigma of “the truth whose living flame goes on burning over the heavy logs of the past and the light ashes of life gone by.”

Arendt seemed to reciprocate Scholem’s expansive admiration. In the review she eventually published of his Major Trends, she declared that Scholem had not only recuperated Jewish mysticism as an essential strand in the larger tradition, but had actually transformed “the whole picture of Jewish history.” The most revolutionary element in Scholem’s exposition was his account of how both the Kabbalah’s teachings about individual responsibility for the universe, and the public activities that grew out of its mystical doctrines, turned the Jew from a passive victim to an agent with free will able to become “a protagonist in the drama of the World.” Thus, in Scholem’s interpretation, Sabbatai Sevi, the Jewish false messiah, who sparked a wildly disruptive international movement in the 17th century, was not just a destructive lunatic, but also the unwitting inspiration for a new model of Jewish political activity. The novel lines of emancipatory speculation unleashed by this mystical redeemer had ramifications far beyond the folds of the religion, Arendt observed. Scholem’s book clarified “for the first time the role played by the Jews in the formation of modern man.” The catastrophe of Sabbatai Sevi, “after closing one book of Jewish history, becomes the cradle of a new era,” Arendt concluded.

Scholem was thrilled with Arendt’s assessment of his work’s significance, calling her review one of just two “intelligent criticisms” the book had received. But the questions of human agency and of hapless victimhood raised by his study — questions of good, evil, and historical responsibility toward the dead and the future — would resurface in the controversy that ensued 15 years later over Arendt’s book about Adolf Eichmann’s trial in Jerusalem. And on this latter occasion, the split in their positions on these topics was so bitter that it destroyed their friendship. Ultimately, Scholem and Arendt were wrestling with the problem of how a person of conscience should address the unconscionable. The argument between them over the mindset of the evildoer continues to be relevant as we struggle to make sense of — and resist — the executors of cruel policy in our own time.

Hannah Arendt’s coverage of Eichmann’s 1961 trial began as a series of articles for The New Yorker, and was subsequently published in book form with the provocative subtitle, “A Report on the Banality of Evil.” For some readers, the work was a paragon of unsentimental truth-telling that revealed how ordinary people could commit atrocities after surrendering their individuality to the faceless bureaucratic mechanisms that typified modernity. But the work has also been vehemently critiqued for allegedly downplaying the enormity of Eichmann’s monstrousness (the terms banality and genocide don’t comfortably mesh) and for the prominent attention Arendt gave to Jewish complicity in the Nazi program through — most glaringly — the work of Jewish Councils in overseeing or otherwise abetting the selection process for deportation to the concentration camps.

The shocked outrage Scholem felt on reading this work by a friend whom he’d formerly described as “one of the best minds” to flee Europe shared features with the larger mainstream Jewish intellectual repudiation of Arendt’s project. But there was another dimension to Scholem’s critique that has received less notice, yet which merits consideration in our current predicament. This particular aspect may also be indebted to moral perspectives Scholem absorbed from the Kabbalah for which, he once wrote, “the metaphysical cause of evil is seen in an act which transforms the category of judgement into an absolute.”

The first letter Scholem wrote Arendt after reading her book — the initial broadside in an exchange that was ultimately made public — began with a number of concessions to Arendt’s position on the Jewish role in facilitating the operation of the Holocaust. Having spent the past 50 years occupying himself with Jewish history, Scholem declares, he is well aware of the abysses in this narrative: “a demonic decay in the midst of life, insecurity in the face of this world […] and a weakness that is perpetually confounded and mingled with debasement and with lust for power.” It’s invariable, he asserts, that in times of catastrophe these tendencies come to the fore. The question that the young were asking in Israel of how all those millions could have allowed themselves to be killed was valid, he allowed. Arendt was right to want people to reflect on such matters. What he cannot countenance is the idea that such a harrowing dilemma could be resolved with a snappy formula. What is unbearable to him, Scholem writes, is the “malicious tone” Arendt has adopted to discuss matters of such profundity. It is Arendt’s “light-hearted style,” the note of “English flippancy” she has favored over that of pity for Eichmann’s victims — just as she has preferred snarkily caricaturing Eichmann himself to seriously analyzing his character — that repulses Scholem.

Nestled inside Arendt and Scholem’s discussion of the nature of evil is a controversy over language. Scholem implies that the cool note of urbane wit Arendt employs not only fails to capture the essence of the event she is witnessing, but actually contributes to the project of dehumanization that Eichmann helped actualize. She loses sight of her subject in the sparkling exercise of her own cleverness. Ironically, in accusing Arendt of practicing facile mockery at the expense of real engagement with the events in Jerusalem, Scholem is charging Arendt with the flipside version of the crime she pins on Eichmann himself: thoughtlessness. Only in Arendt’s case it is an excess of linguistic dexterity that fouls up her thinking rather than the deficit she perceives in Eichmann.

Arendt’s diagnosis of Eichmann’s banality was not intended to minimize the harm he inflicted, as she attempted repeatedly to make clear in response to attacks against her work, but to underscore his mediocrity. In Arendt’s view, Eichmann’s astonishing superficiality, on display throughout his trial, could be understood as even more ominous than the character of some classic satanic figure since it represented an easily communicable strain of wickedness. Eichmann’s banality underscored the susceptibility of unremarkable men and women to becoming collaborators in spectacular crimes under pressure of the right kind of leadership and within the self-contained moral universe of bureaucratic systems that enabled perpetrators to shuck off their sense of personal responsibility. As Arendt wrote Scholem, having watched Eichmann in action she had ceased to believe in the idea of “radical evil” that had been part of her philosophical lexicon in her earlier work on totalitarianism. Evil, she now proposed, had no depth, “and therefore has nothing demonic about it. Evil can lay waste the entire world, like a fungus growing rampant on the surface.”

Face to face with the phenomenon of Eichmann in Jerusalem, Arendt became convinced that his actions betrayed not a monstrous personality, but a total inability to think for himself. And her principal evidence for Eichmann’s cognitive ineptitude was his spluttering language. Over and over, Arendt marvels at the stupendous infelicity of Eichmann’s word choices and his reliance on stock phrases. “Dimly aware of a defect that must have plagued him even in school — it amounted to a mild case of aphasia — he apologized, saying, ‘Officialese [Amtssprache] is my only language,’” Arendt recounts at one point. However, she continues, “officialese became his language because he was genuinely incapable of uttering a single sentence that was not a cliché.” The ghastly incoherence of Eichmann’s hackneyed speech reflected the unoriginality of his mind, a thought process fatally clogged with grandiose, vacuous slogans.

Arendt later confessed herself to be continually fighting back laughter while she sat in the stands listening to him. In her book, she noted that the taped police examination of Eichmann offered a veritable gold mine to the psychologist “provided he is wise enough to understand that the horrible can be not only ludicrous but outright funny.” Some of this comedy, she went on, couldn’t be captured in English, however, since “it lies in Eichmann’s heroic fight with the German language, which invariably defeats him.”

Arendt’s portrait of Eichmann has been challenged repeatedly over the years. But the recent biography by Bettina Stangneth, Eichmann Before Jerusalem: The Unexamined Life of a Mass Murderer, has been seized on by Arendt’s critics as the most devastating rebuttal to her argument. Drawing on an enormous trove of personal and official documents that Arendt did not have access to, Stangneth reveals Eichmann to have been a far stronger character than the mindless functionary Arendt depicted.

Yet while it’s true that Eichmann’s anti-Semitism and overall devotion to the National Socialist party come through more forcefully in Stangneth’s work than in Arendt’s book, one does not necessarily come away from Eichmann Before Jerusalem feeling that he has been exposed as a fanatic, frothing ideologue. Eichmann was an exemplary Nazi from the start of the movement until the end, but Arendt never suggests otherwise. What does change dramatically is the impression of Eichmann’s self-importance. He is a monster of self-regard and self-interest, savagely expedient in advancing his fortunes, with a fanatical hunger to be recognized as a great historical figure coupled to an instinct for personal survival at all costs. One of the most striking images in the book is of Eichmann steadfastly compiling a colossal file of press cuttings about himself for years — up until the final months of the war. Even when the coverage was negative, the sight of his name in print proved an irresistible intoxicant to Eichmann. “Nobody else was such a household name in Jewish political life at home and abroad in Europe as little old me,” he later boasted to one friendly interviewer.

What Arendt failed to register in Jerusalem was that the stumbling, jargon-y, nonsensical joke of Eichmann’s speech was intensely effective at maximizing his wiggle room before the law. By being as unclear as possible, Eichmann cast not just his own testimony but the facts themselves into a soupy haze of ambiguity. Moreover, it’s plain that by doggedly mangling the language Eichmann struck the Achilles’ Heel of high intellectuals like Arendt, triggering an urge to snicker even when the subject under discussion was the near annihilation of European Jewry. A buffoon who doesn’t even have the mental wherewithal to defend himself except in comically inarticulate banalities is not someone an intelligent person with a liberal bias readily sends off to the gallows. What Arendt missed above all was the possibility that mediocrity could be performed, and that the man under trial for his life might be a versatile shape-shifter, constantly adjusting his clown act to make his character appear — not innocent of the acts he was accused of — but potentially exculpable by virtue of inanity.

¤

Scholem’s fascination with Kabbalah was born in part out of frustration with the 19th-century advocates of so-called rational Judaism, the proto-progressive Jewish philosophers who wanted to purge the religion of all but its most universally acceptable, benign, anodyne features. “Jewish philosophy paid a heavy price for its disdain of the primitive levels of human life,” he wrote. It effectively became out of touch with the experience of ordinary men and women. To the Kabbalists, on the other hand, evil was always “one of the most pressing problems,” Scholem wrote, and they were “continuously occupied with attempts to solve it.” In so doing, they spoke to the people’s terrors and hopes, giving cosmic significance to both historical trauma and the anguish of everyday life.

One way of thinking about Scholem’s objection to Arendt’s “slogan” (as he called it) about evil’s banality was that it did not connect to people’s lived experience of suffering, which called out for empathy not aperçus. In the complex theological architecture of Kabbalah, evil is a quality originating within the Divine itself, which has somehow become isolated from tempering attributes. On the simplest level, the Divine aspects of judgment and wrath become detached from mercy and love, spawning the evil forces that plague humanity.

Scholem accuses Arendt of having let her sense of critical judgment run away with her to such an extent that she becomes numb to the human reality at issue. Of the decisions made by the leaders of the Jewish Councils, he acknowledges that, as is true of humanity in general, some were indubitably villains while others were saints. What’s incontestable, he avows is that they were compelled to make decisions under conditions of such unique, immeasurable horror that their quandary cannot be reconstructed. He himself, Scholem declares, is incapable of judging these representatives of Jewish communities. For a tragedy of such magnitude, sheer compassion for the collective — love — must guide the intellectual response at every step.

Scholem doesn’t ask Adorno’s question as to whether poetry is possible after the Holocaust, but he does suggest that in reporting on the Holocaust snide journalism may only further obscure the truth.

¤

Were he to have viewed today’s battlegrounds, physical and moral, I suspect Scholem would have felt that expressing a solemn, absolute solidarity with those suffering the abuse of power constituted a more substantial form of resistance than even the most scintillating satiric takedown of those in command. We get pleasure from the fool, and turning agents of cruelty into fools risks making them a source of amusement whose risibility we secretly, guiltily itch to keep watching. The solidification of the status quo as entertainment (however dark) becomes its own form of normalization. (I remember hearing someone, an erstwhile Clinton supporter, crowing in the immediate aftermath of the elections, “I just can’t wait to see Melania on Saturday Night Live.”)

Scholem’s final objection to Arendt’s famous phrase returns to the problem of Eichmann’s character. What was really going on in his head when he supervised the transportation of hundreds of thousands of people to the extermination camps? If Hitler’s project originated in a politics of wrath, what enabled its ongoing implementation by all those executors among whom Eichmann’s name looms so large?

In Arendt's view, the problem with Eichmann's thinking boiled down to the fact that he was not thinking very much — not nearly enough. Had he been taught to think properly, she argues, Eichmann would necessarily have developed a moral intelligence. Scholem situates the problem elsewhere. Rather than focusing on Eichmann’s thought process, Scholem concentrates on his feelings — Eichmann’s passions. Thus, Scholem does not discount the notion of the “banality of evil” because Eichmann and the other Nazi henchman are zealous anti-Semites, or raging believers in any larger ideology. What Scholem singles out as the flaw in Arendt’s phrase is that it fails to recognize the sheer pleasure involved in being a successful Nazi. Scholem would never have discounted the idea that the Nazi bureaucracy facilitated the movement’s genocidal mission. But he couldn’t accept that the bureaucracy was managed by homogenous, robotic drones fulfilling the will of the master. The operators of great bureaucratic mechanisms can still themselves be vainglorious individuals fueled by low appetites. “I don’t picture Eichmann, as he marched around in his SS uniform and relished how everyone shivered in fear before him, as the banal gentleman you now want to persuade us he was, ironically or not,” Scholem wrote Arendt.

The more complete portrait of Eichmann that has emerged in recent years validates Scholem’s impression. From the descriptions and interviews of Nazi functionaries he himself has read, Scholem reports, it appears, “The gentlemen enjoyed their evil, so long as there was something to enjoy. One behaves differently after the party’s over, of course.”

The enjoyment Scholem refers to is not simple sadism, but the thrill of experiencing a wild inflation of personal power — power over others, power to do as one privately wishes quite apart from any larger, theoretical ideology. What Scholem identifies in Eichmann is the excitement of feeling oneself to be a god.

There are plenty of directions we can turn our eyes today to test the respective theses of Arendt and Scholem about the mentality of the characters crafting policies that cause suffering to the innocent and harm to the planet. Are we seeing conformist functionaries mindlessly carrying out their nefarious duties? Or are we watching numbers of highly self-motivated individuals eagerly, sometimes even gleefully indulging an unconscionable greed for power in all its earthly forms? In Arendt’s schema, given enough basic intelligence, the person who doesn’t know how to think can be taught to do so. But the problem presented by someone in a self-centered passion is different. The person who thinks himself a God has to be removed from power before the contradiction of their fantasy becomes a capital offense.

George Prochnik’s most recent book, Stranger in a Strange Land: Searching for Gershom Scholem and Jerusalem was a New York Times “Editor’s Choice.”

Listen to our conversation with George Prochnik on the LARB Radio Hour.

LARB Contributor

George Prochnik’s most recent book, Stranger in a Strange Land: Searching for Gershom Scholem and Jerusalem was a New York Times “Editor’s Choice” and has been long-listed for the Wingate Prize in the United Kingdom. His previous book, The Impossible Exile: Stefan Zweig at the End of the World, won the National Jewish Book Award for Biography/Memoir in 2014. He is editor-at-large for Cabinet magazine.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Tapestry of Fame and Failure

Noah Kennedy reviews George Prochnik's "Stranger in a Strange Land."

Why Arendt Matters: Revisiting “The Origins of Totalitarianism”

Roger Berkowitz reviews Hannah Arendt’s landmark “The Origins of Totalitarianism,” framing the book within the context of contemporary politics.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!