From Moscow Art Theatre to Catfish Row

Mamoulian, perhaps more than anyone else, defined the original racial landscape that became the setting for Porgy and Bess.

By Kurt JensenFebruary 28, 2012

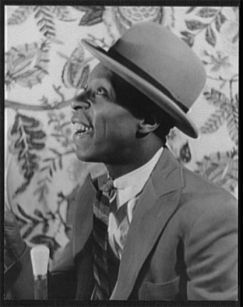

Portrait of John W. Bubbles, as Sporting Life in Porgy & Bess by Carl Van Vechten

OVER THE STAGE DOOR at the Richard Rodgers Theatre, home to The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess, hangs a sign reading, “For Residents of Catfish Row Only!”

Going by the exclamation point, it’s all in good fun: there’s no latter-day Lester Maddox at work in the show’s marketing department. Performers from the original 1935 production, who knew harsh prejudice and “For Colored Only” signs, and many of whom disliked wearing bandannas (choral director Eva Jessye recalled telling them, “It’s just a custom, honey.”), would probably not enjoy that sign. Instead, they would likely have joined Maria, the matriarch of that South Carolina ghetto, in shouting, “Oh, hell, no!”

Gershwin purists, upset by the production’s many liberties, are shouting it now, too, but audiences new to this latest incarnation of George and Ira Gershwin’s “folk opera,” based on the 1925 novel and 1927 play Porgy, are unlikely to care much about any of the substantial alterations to the score and book. Even Anthony Tommasini, the classical music critic of The New York Times, observed, “I cannot be sure, but a good third of the original Porgy and Bess seems gone in this adaptation.” Terry Teachout, near the end of his eviscerating review for The Wall Street Journal, stopped to claim, “I’m no Porgy purist,” but his litany of complaints, including the lack of the original dialect, screams otherwise.

I’m not a Gershwin purist either, but I am a Rouben Mamoulian purist — by necessity, since I’m writing his biography. While Mamoulian may be best remembered for directing the original Broadway casts of Oklahoma! and Carousel or Hollywood classics like Love Me Tonight and Silk Stockings, it could be argued that he had more to do with the evolution of Porgy and Bess than any other single artist, excluding, of course, the opera’s composer. His influence on Porgy and Bess is often under-emphasized, which is perhaps inevitable when one works with a genius such as George Gershwin.

Born in Tbilisi, Georgia in 1897 to an Armenian family, Mamoulian relocated to London at age 25 and almost immediately began directing plays. The following year he arrived in America, and by 1927 he was directing the stage play Porgy (adapted by Dorothy Heyward from her husband DuBose Heyward’s novel), which would become the basis of the 1935 Gershwin opera.

Today, when critics talk about the “original” version of Porgy and Bess, they are discussing a phantom work, since the original production slashed away at the script as well. A complete version of the opera would run about four hours; the 1935 Boston premiere ran three and a half, from which Mamoulian and the Gershwin brothers cut another 45 minutes before bringing the show to New York. The new incarnation at the Richard Rodgers, with nearly all the recitatives changed to dialogue, runs a brisk two and a half with a single intermission. Director Diane Paulus, book adapters Suzan Lori-Parks and Diedre L. Murray, and the Gershwin heirs all want this production to be a living, breathing entity for widespread audiences, not a museum piece occasionally revived by opera companies for a tiny slice of patrons. Their clear desire, eight decades after it was written, is to finally make Porgy and Bess into a long-running commercial hit.

In order to do this, grievous heresies have not, in my estimation, been committed — with a single exception (more on this in a moment). The music, thankfully, is all pretty much still there, but the production sounds quite thin. It was written for an orchestra of 44 and a cast of 70 (not including the children’s brass band that led the parade to Kittiwah Island), nearly all of whom were singers. It was meant to pin an audience to its seats, crashing into them like a sonic wave. This version features no brass band and has a 22-piece orchestra and a chorus of just 15, both working full-tilt. (To be fair, the full ensemble only ran from Oct. 10 to mid-November, 1935. After that, plummeting receipts had the Theatre Guild laying off chorus members.) Still, it is impossible not to judge Porgy by its operatic roots — and by that comparison the current version is redolent of a small college production. No one’s going to be pinned to any seats. As Charles Isherwood, theatre critic of The New York Times wrote, it’s “musically underpowered and emotionally tepid.”

What needs to be said here is this: Porgy and Bess is a work that has been in a constant state of abridgement and expansion for 76 years. Each Porgy and Bess has been shaped according to the attitudes of its time and the demands of the specific talents (and financing) behind the productions. The first incarnation, which ran for just 124 performances on Broadway, famously deleted the big dance opening “Jazzbo Brown’s Blues” (too much like Harlem, not enough like Charleston, Mamoulian decided) and the Buzzard Song (the aria reminded Mamoulian of “The Song of the Viking Guest” in Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera Sadko). It also had several hundred bars cut out, including a lengthy deletion in the last act in which Mamoulian reinserted his famous “Symphony of Noise” — the sounds of Catfish Row coming to life — that he’d used in the 1927 play he also directed. The libretto was first converted to dialogue in 1942 for Cheryl Crawford’s successful Broadway revival, and the n-word (used 14 times in the original, down from 44 in the play and 59 in the novel) was deleted in the 1952 Robert Breen production with Leontyne Price, William Warfield and Cab Calloway. The Houston Grand Opera roared back with a much-celebrated “full” version in 1976; in 1986, Porgy, a paraplegic in a goat cart, graduated to a disabled man with a crutch for the Glyndbourne Festival production in England directed by Trevor Nunn, and the goat’s been receding ever since.

As for the new heresy, it’s dramaturgical. Lori-Parks and Murry eliminate the lawyer characters: black Frazier, a shyster who sells cheap “divorces,” and white Archdale, who reprimands Frazier and is the lone element of white compassion in Catfish Row. Now, Maria, the proprietor of the cookshop, sells Bess her “divorce” from Crown, which is confusing enough, since it’s not even made clear what Maria’s usual function is.

In other spots the current adaptors have added dialogue that condescends to the audience and degrades the Gershwins. “Whatcha been up to, Porgy?” asks a Catfish Row resident just after Bess (Audra McDonald) moves in with him. “Nothing,” says Porgy (the splendidly robust Norm Lewis), with a bit of a leer. He then sings “I Got Plenty of Nothing,” a song that already makes explicit just what “Nothing” he’s singing about. (In the original, Porgy just starts singing that song out his window, and the audience fills in the rest. He is simply a happy man, not a man who brags about gettin’ some.)

This production uses no dialect, but the original dialect, with the exception of some Gullah language such as “buckra” (which means “white man” and is also now deleted), wasn’t that accurate to begin with. The novel written by Heyward, the play written by his wife, the opera, and even the 1959 film that Mamoulian began until Sam Goldwyn fired him (over a demand for more money) and replaced him with Otto Preminger, all suffer from the longstanding historical fault of whites deciding how black folks should really sound and act.

As well intentioned as the Heywards were, they were no closer to the internal lives of poor African Americans in Charleston than Joel Chandler Harris was when he wrote his Uncle Remus stories. Paulus, Parks, and Murray have not been vocal about this, but there’s some reclamation going on, thank you very much. You’re unlikely to hear them mentioning it publicly because it’s tough enough to get a show on the boards without sticking one’s head into America’s racial hornets’ nest.

Mamoulian, perhaps more than anyone else, defined the original racial landscape that became the setting for Porgy and Bess. An alumnus of the Moscow Art Theatre, he filled the 1927 production with semi-professional actors who breathed life into Catfish Row where the Heywards had only indicated vaguely defined colors and sounds. In 1934, he had to lobby the Theatre Guild to become Gershwin’s choice of director for the opera. He made changes to the 1935 opera score, and he tried twice on his own — at Columbia and United Artists — to get a film made before Goldwyn acquired the rights in 1954. Most of his plans were realized in that film, which starred the dubbed Sidney Poitier as Porgy and Dorothy Dandridge as Bess. When Goldwyn fired him in July 1958, Mamoulian was broken and embittered, and for the rest of his life he referred to Preminger as “the mephitic scum.” (I’ll pause here while you look up “mephitic.”)

Because of the great success of the 1927 Porgy, which had a lengthy Broadway run and toured across America and Europe, Mamoulian became permanently identified with what was then called “Negro talent.” For the next 40 years„ the director was offered work on at least one script for a “Negro play” or “Negro musical” per year, although he usually sent most scripts away unread. Having gone through his vast collected papers at the Library of Congress, I can report that he appears to always have taken the time to read that material, whether it was promising work by the then-obscure Zora Neale Hurston (Polk County) or stale wheezing pieties from Dailey Paskman, a former purveyor of minstrel shows (Rise Above It). Mamoulian remained always watchful for another potential Porgy.

His other shows that employed African-American talent were St. Louis Woman (1946), a horse-racing musical by Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer, in which he removed crude sexual humor and a subtext of light-skinned blacks looking down on dark-skinned blacks, and Lost in the Stars (1950), the Maxwell Anderson / Kurt Weill musical about racism and redemption in South Africa, based on Alan Paton’s novel Cry, The Beloved Country, which reunited him with Todd Duncan, the original singing Porgy.

Although Mamoulian helped birth both Porgy and Porgy and Bess, he did not necessarily possess a profound understanding of race relations in America. Judging by his correspondence, African-American performers did not read him as racist, but it’s chilling to see some of the notes he took on actors he rejected for the Porgy and Bess film: “Not very Negroid” and “not Negroid enough,” read two of them. And this was in 1958, shortly after he’d talked Poitier into taking the film after he had balked at the crude portrayal of a Catfish Row crap game. As with the Heywards, and perhaps inevitably for the time, this was a white man deciding what racial properties black performers should have.

In 1973, Mamoulian recounted his experience with some of the performers to William Becvar, a dissertation writer, speaking of the 1927 rehearsals for the play Porgy:

[T]he first two weeks were absolutely murder because they tried to act white. And I said this was going to be a disaster. Until finally I got indignant enough to give them a long talk about their greatest contribution being music and rhythm and emotional commitment. That broke the ice and from then on they went to the other extreme where you couldn’t control them. So the great problem was to keep that inner passion and the intensity of expression and yet keep the form permanent. You can’t improvise on the stage. Finally, they got it and the result was thrilling.

Straight-up racism, inchoate cluelessness, or something in the middle? When it came to lecturing his actors, as witnessed by his tirades during rehearsals for the stage musicals Oklahoma! and Carousel, the Armenian-born Mamoulian’s ego was colorblind, and he was the master of the well-timed tantrum.

His opaque racial politics notwithstanding, Mamoulian eventually found that his time with the opera had an uncharacteristically emotional ending for him.When he finished his work on Porgy and Bess and was beginning his train journey home to California in November 1935, he told a second disseration writer, Bennett Oberstein:

As I started walking down the ramp, I saw a red runner of carpet leading to the train. Then I heard a band, playing the “Orphan’s Band Theme” from Porgy and Bess. I thought I was crazy. I saw, as I came down to the coach, where I had my reservation, the whole cast of Porgy and Bess and the whole orphan’s band going to town and the goat and the cart. That’s the way they saw me off to Hollywood. I remember when the time came to get inside, I could see through the large windows on the side, nothing but a sea of black faces pressed against the window, and looking at me with such love that, you know, I broke down and cried for five minutes. I just couldn’t help it. I loved them and love is reciprocated. You love something and you get it back. And unless there is love, you never get marvelous results.

LARB Contributor

Kurt Jensen reviews films for the Catholic News Service. His biography Rouben Mamoulian: The Art of Gods and Monkeys will be published by University Press of Mississippi in 2013.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!