From Aspiration to Constriction: On Three New Books Examining Change in China

Martin Laflamme reviews three recent books that help understand the opening of China during the 1980s–2000s, and its closing again under Xi Jinping’s rule in the 2010s.

By Martin LaflammeApril 1, 2024

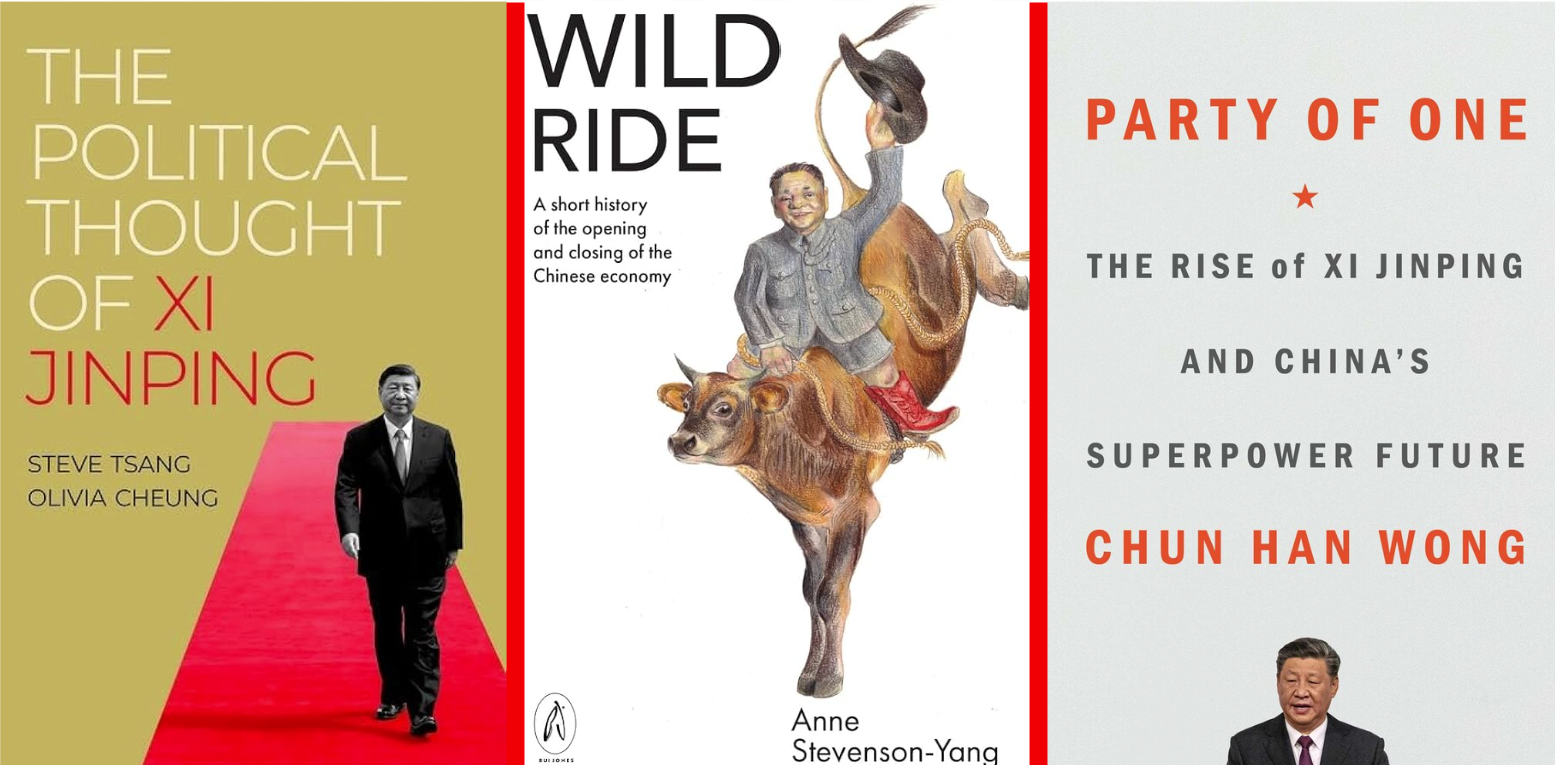

Party of One: The Rise of Xi Jinping and China’s Superpower Future by Chun Han Wong. Avid Reader Press. 416 pages.

The Political Thought of Xi Jinping by Olivia Cheung and Steve Tsang. Oxford University Press. 296 pages.

Wild Ride: A Short History of the Opening and Closing of the Chinese Economy by Anne Stevenson-Yang. Bui Jones Limited. 176 pages.

THE DECADE THAT preceded the Tiananmen tragedy of 1989 was a remarkable period in the history of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). In the drab years following Mao Zedong’s death in 1976, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) still controlled most aspects of a citizen’s life. To marry, divorce, have children, change jobs, or travel, one needed to seek its permission. Having a foreign friend was suspicious. Dating one was forbidden.

Then, early in the 1980s, the reforms of Deng Xiaoping, who had secured power in 1978, started to kick in. Markets popped up in every quarter. Budding entrepreneurs began peddling a range of goods hitherto unimaginable. Economic growth exploded—GDP grew 15 percent in 1984 alone—and many got richer, some gloriously so. Individual autonomy expanded as well, in lockstep with economic freedom. For the first time in years, people were hopeful about the future.

The consequences were sweeping. At the beginning of the 1980s, Anne Stevenson-Yang writes in Wild Ride: A Short History of the Opening and Closing of the Chinese Economy (2024), her slim but engaging personal account of the PRC’s economic miracle, there were less than 200 newspapers in the country. Ten years later, the number had ballooned to nearly 2,000, and many were pushing hard against tight but slowly stretching censorship boundaries. Students grew bold and took to organizing marches to protest against all sorts of issues. Change was all over the place. It was messy. It was uneven. It was erratic. But that “is what made life in China in the 1980s exciting.”

At the time, many observers thought the country had turned a corner. It remained authoritarian, but it seemed to have shed the worst of its despotic ways. With hindsight, though, such optimism was misplaced. The 1980s was a historical incongruity rather than a clean break with the past. True, it was not the only period of openness and experimentation. Others followed, particularly around the turn of the millennium, but these were not as freewheeling and open-ended, and all proved short-lived. In recent years, Stevenson-Yang laments, China has once again been closing in.

To understand why, we must attempt to peek into the mind of Xi Jinping, one of China’s most powerful leaders of modern times. As he approached the pinnacle of power in the late 2000s, Xi grew increasingly concerned. Wherever he turned, he saw signs of moral decay. He recognized that Deng’s economic reforms had made the country rich, but they also enabled corruption and excesses of all kinds. This weakened people’s belief in socialism and the Party’s authority. If nothing was done, Xi feared, the CCP could lose its grip on power. A course correction was necessary—and the sooner the better.

In The Political Thought of Xi Jinping (2024), Steve Tsang, director of the China Institute at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), and Olivia Cheung, a research fellow at the same institution, describe how Xi, upon assuming power in 2012, set about remolding the Party, people, and politics. They parse his speeches and public comments, as well as PRC policy documents, and bring into fuller relief his views on governance. The result is a piercing—and concerning—analysis of the PRC’s trajectory and its implications for the rest of the world. It should be required reading for anyone with an interest in contemporary China.

One of the most disturbing problems for Xi was ideological laxity. In a speech he delivered in the summer of 2013, less than a year after assuming power, he made his views clear: too many Party members were “skeptical about communism.” They believe in “ghosts and gods” rather than “Marx and Lenin”: “They lack strong principles. Their morality degenerates.” Worst of all, “[s]ome even yearn for Western social [i.e., political] institutions and values, losing confidence in the future of socialism.” This had to change.

The first order of business thus consisted in ramping up reeducation. In the fall of 2013, the Central Party School began offering training on Xi’s “important remarks,” which mostly consisted of speeches he had delivered on governance. Research centers devoted to his “Thought” then sprang up across the country—there are dozens of them nowadays. At all levels, government officials were required to attend study sessions to familiarize themselves with the views of China’s new supremo.

This was just the beginning. In 2017, the Party launched an app called Xuexi Qiangguo, a pun on Xi’s name, which can be interpreted as “Study Xi [thought] and make the country strong.” Its use became all but mandatory across the government. Local authorities also revived propaganda strategies last employed in the Cultural Revolution (1966–76) and mandated that hundreds of thousands of loudspeakers be reactivated, from the inner core of Shijiazhuang to the outskirts of Tianjin, to broadcast content from the app three times a day. From kindergarten to university, school curricula were also adjusted to boost content on Xi Jinping Thought. As the man himself put it, the goal is “to ensure that red genes seep into the blood and soak into the heart.”

Xi’s obsession with ideology is grounded in his reading of history. He firmly believes the Soviet Union collapsed because its people and leaders lost faith in communism. “Facts have proven, time and again,” he once said, “that the wavering in one’s ideals and convictions is the most dangerous form of wavering.”

This quote comes from Party of One: The Rise of Xi Jinping and China’s Superpower Future (2023), a thoughtful chronicle of China under Xi by Chun Han Wong, a reporter at The Wall Street Journal. Wong spent five years in Beijing before being forced out in 2019 when the government refused to renew his press card. Unlike Tsang and Cheung, who look at Xi Jinping Thought through a theoretical lens, Wong’s approach is largely empirical. He has a foreign correspondent’s eye for details illustrating deeper verities, but he never loses sight of the historical context, and often supplements his observations with perceptive digressions into China’s imperial past. One example is Xi’s celebration of Confucius as a means to “inspire virtue among officials […] even though the party had traditionally condemned the ancient sage as a feudal relic.” Another is Xi’s fondness for the Legalist tradition, a school of thought that, like Confucianism, emerged in the Warring States period (ca. 475–221 BCE). Unlike the benevolent ideas promoted by Confucius, however, Legalism endorsed “harsh autocratic rule as a way to impose order” and continue the status quo.

Promoting ideology is one thing; having people believe it is quite another. To bring people to his side, Xi and his propagandists have mined the Party’s rich lore of myths to craft a vision that is powerfully enticing to Chinese patriots. Theirs is a “nation of heroes,” of selfless men—and a few women—who, for more than a century, struggled relentlessly against feudalism, Western imperialism, and Japanese fascism. By force of will and at the cost of enormous personal sacrifice, guided by a Party that neither flinched nor flagged, these “heroes” crushed their enemies and made China stand tall once again. In Xi’s version of history, the advent of the Party is not a break with the past but the logical and natural successor to the sumptuous and timeless history of the Middle Kingdom. Similarly, the Party’s socialist values are not a foreign import but “quintessentially Chinese.” The goal of this narrative, Wong writes, is to fire up “rousing patriotic passions for one-party rule.”

Never mind that much of this narrative is built on distorted or fabricated facts. The Party will defend it ferociously; the most obvious way consists in blocking access to archives that contain inconvenient evidence. Another takes the form of coercive legislation. In 2018, for instance, the National People’s Congress, China’s rubber-stamp legislature, adopted the “Law on Protection of Heroes and Martyrs,” which calls upon all members of society to honor the nation’s paragons. The edict also states that “[i]t is forbidden to distort, smear, desecrate, or deny” their actions and memory. Since the government has certified about two million heroes and martyrs, Wong writes, it is risky for historians—to say nothing of online jesters—to delve with too much verve into their debatable deeds. In general, anything questioning the Party’s narrative amounts to “historical nihilism.” And that, too, shall not go unpunished.

Ideology is not just for the plebes or Party apparatchiks. It is also for captains of industry. In 2016, Xi told a group of business leaders that they must honor the “glorious tradition of listening to the party’s words and following the party’s path.” Two years later, Wong adds, Xi warned another group, which included representatives from tech giants such as Tencent and Xiaomi, that commercial success was “secondary to the primary goal of boosting China’s technological security.”

To ensure the corporate world would toe the line, Xi squeezed it hard to make room for the Party. Between 2012 and 2016, Wong shows, the proportion of nonstate enterprises with Party cells grew from 54 percent to 68 percent. In foreign companies, full or partially owned, it reached 70 percent. The head of the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China, Jörg Wuttke, perhaps put it best: Beijing wants “foreign companies to ‘tremble and obey.’”

¤

While Xi believes that relentless ideological indoctrination is necessary to ensure that the CCP does not follow its Soviet counterpart into historical irrelevance, he knows it is not enough. Discipline is equally important. And when Xi became Party boss in November 2012, he found his underlings sorely lacking. Hence his second obsession: “Party building,” shorthand for transforming the CCP into a tight “Leninist instrument for governance and control.” According to Tsang and Cheung, the key elements of that program include centralized authority, ideological uniformity, organizational resilience, and successful penetration of non-Party structures. None of that playbook is new. Much of it comes straight from How to Be a Good Communist, a thin but influential screed published in 1939 by Liu Shaoqi, a Party founder and Mao’s anointed successor until he fell out of favor in the mid-1960s. Under Xi, Liu’s work is once again required reading.

One of the hallmarks of poor discipline is corruption. It stains the image of the Party and undermines its legitimacy. But for Xi, it is much more than that. It is a symptom of ideological laxity, a sign of disloyalty to the Party and even to him personally. It is the mother of all sins, and by the early 2010s, it had become rampant. Stamping it out was urgent.

The hammer came down hard and fast. As soon as Xi took office, he turned the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, a hitherto overlooked and underused institution, into a powerful—if opaque—tool of control. Between 2012 and 2021, Tsang and Cheung tell us, just over four million cadres were investigated and punished. Most of these were relatively minor officials, “flies” in Party parlance, but Xi also went after several big “tigers.” The most important of these was Zhou Yongkang, a former member of the Standing Committee of the Politburo—China’s highest decision-making body—and the most senior official purged in decades. Though it seemed to fall disproportionately on potential rivals of Xi, the campaign spread far and wide, and soon affected all government officials, not just Party members. Those caught up had few opportunities to defend themselves, and since conviction rates in courts approach 100 percent, coming under investigation is, for all practical purposes, a guilty verdict.

Graft-busting has been a hit with the Chinese public. But with so many Party officials sanctioned, some might wonder whether the real problem is not structural. The Party has a well-rehearsed dodge for that accusation: character smearing. This explains why, Wong writes, offenders are inevitably presented as rotten and their reputations tarnished with “lurid details of greed and sexual deviance.” The goal is to reinforce “the party’s claims that corruption stems from individual degeneracy rather than systemic flaws.”

¤

Like millions of Chinese people, Deng Xiaoping and his family suffered greatly during the Cultural Revolution. When he returned to power in the late 1970s after the death of Mao, Wong writes, he “sought to inoculate the party from the perils of one-man rule.” He made sure that “[s]enior leaders shared power,” but he also “encouraged timely retirement, and made plans for orderly succession.” When the constitution was revised in 1982, Deng imposed term limits on the two top government positions of president and premier, though he stopped short of doing the same on the Party or its all-powerful Central Military Commission.

Because power remained concentrated in Party hands, these norms never really took hold, and Xi had little difficulty taking them down. Today, he stands alone at the top, the first subject of a sustained personality cult since Mao, in full control and with no visible signs of opposition. Secure in his role, might he ease off on his anti-corruption and ideological campaigns? That seems unlikely. Tsang and Cheung correctly point out that the prime value of these campaigns lies not in the goals they pursue but in the processes they unleash. Like Mao before him, Xi believes that “the Party will decay unless it is subject to constant rectification.” We had better get used to it.

This also means the PRC’s aggressive foreign policy is set to continue. Because “national pride in a tightly guided narrative of China’s history” and “the greatness of […] the Party” is so important to Xi’s legitimacy, the two SOAS scholars write, the nation’s diplomats will continue to defend the country’s honor “assertively if not aggressively.” That this approach fuels rising tension with many parts of the world is of secondary importance.

None of this will be surprising to Stevenson-Yang. Now living in the United States, she last visited China as a tourist, just before COVID-19, with her children and husband, a PRC national she met during her first stint in the country in the 1980s. The experience was bittersweet. The country she fell in love with and lived in for a quarter century is gone. Four decades ago, foreigners were welcome. Today, exit bans and arbitrary detentions are a “significant risk.” She laments that she probably won’t return until there is political change.

It is a tragedy that so many people feel the same, but there should be little doubt as to where the blame lies.

LARB Contributor

Martin Laflamme is a Canadian Foreign Service Officer who has served in Tokyo, Beijing (twice), Kandahar, and Taipei. The views presented here are his own.

LARB Staff Recommendations

History as Dissent: On Ian Johnson’s “Sparks” and Tania Branigan’s “Red Memory”

Craig Calhoun reviews two books on history and memory in China: Ian Johnson’s “Sparks: China’s Underground Historians and Their Battle for the...

The Great Leap to Valhalla: Wagner in China

Melissa Chan writes about the performance of Wagner operas in China.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!