Framing 1966: Jon Savage on the Year the 1960s Exploded

Scott Timberg takes a spin through “1966: The Year the Decade Exploded” by Jon Savage.

By Scott TimbergJanuary 1, 2018

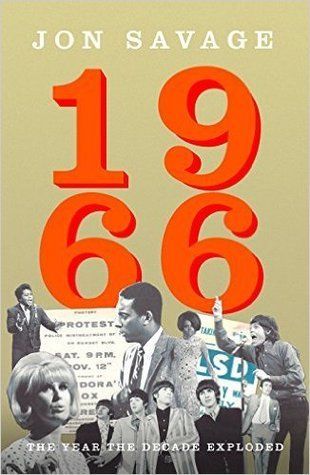

1966: The Year the Decade Exploded by Jon Savage. Faber & Faber. 620 pages.

SO, WHAT was that all about? What was the geist of that particular zeit? What made it happen, and what made its boom stop happening? At the very least: What did it really sound like, and why did it lilt and roar like it did? These are the questions any ’60s-obsessed soul should ask about 1966 — the decade’s key turning point, the leading tone that brought on the more celebrated 1967 (whose anniversary we celebrated last year).

These are also the question Jon Savage, the veteran British rock journalist, asks in his recent book 1966, about a year just beyond the half-century mark. (His book, released in 2016, comes out in paper on January 2, 2018.) And the answers tell us something — probably something unsettling — about where we in the Anglophone world are headed.

1966 wasn’t just the sound of the Byrds’s chiming 12-strings, the Beatles’s tape-loops, Otis Redding’s horns, Dusty Springfield’s pleading, and what Bob Dylan would call his “thin, wild mercury music.” It was a year of hundreds of odd little one-off singles — many of them turned out by deranged teenagers in their folks’ California garages — and a year in which black/white relations, the war in Vietnam, the mentality of Baby Boom teenagers, the legal status of homosexuality in Britain, other sex and gender norms, and the terms of film and visual art would shift in consequential ways.

It wasn’t all peace and love — for all the liberty and lust there was also tangible anxiety about impending nuclear warfare, as well as a nasty backlash by the establishment. And for all the great music it was also the year Mick Jagger collapsed from exhaustion, when the Beatles stopped touring after being physically assaulted in Manila, and when Dylan crashed his motorcycle and went into seclusion. But 1966 was also, as Savage says with his subtitle, “The Year the Decade Exploded.”

“I started writing the book partly to combat historians who discounted it,” Savage — born Jonathan Sage in 1953 — says from his home on the Welsh coast. “‘The sixties didn’t really happen, it was just 200 people in London; it wasn’t about Terry and Julie who lived in Wigan…’ Fuck that! Whatever the Yardbirds were doing or saying, they were in Rave, they were in Mirror — they were everywhere.” Tens of thousands of people in the United Kingdom, he says, followed the musicians, film stars, and fashion models of Swinging London (or Manchester, or Liverpool). And American cities — New York, Boston, Chicago, San Francisco, Los Angeles — had highly developed youth-culture and music scenes as well.

“There’s been a right-wing/neo-conservative attack on the ’60s here in the UK for 30 years,” Savage says. “But it was a period of genuine freedom.”

Every era marks both the opening of something new and the close of something else. While 1966 engaged “the ’60s” — an era not entirely contiguous with the actual decade — and prepared the ground for both the Summer of Love and the larger Age of Aquarius, it was also the end of a long-running epoch. “In Britain it was the end of the Victorian Age,” says Savage, dating the pivot to Winston Churchill’s 1965 funeral, which left the 12-year-old future author upset. “I was super pissed,” he recalls, “because it was on television all day so ‘Top of the Pops’ wasn’t on!”

¤

The ’60s, and ’66 in particular, are primarily remembered for their music, but it was a rich and transitional era for film, literature, and race as well. Hollywood took its sweet time catching up with the social and cultural transformations, longtime film critic and Criterion Collection programmer Michael Sragow points out. “It wasn’t a breakthrough time,” he says, “but a time when you could see the fractures.” Hollywood was still turning out road shows, big-budget adaptations of best sellers, and Biblical spectacles.

French, Swedish, Italian, and Japanese film, of course, was veering into all kinds of thematic and sexually and politically adventurous territory. But Hollywood would wait until the ’70s to mature. “There was a lot of ferment going on,” Sragow says. “Not necessarily revolution yet, but creative unsteadiness.”

It would take 1967’s Bonnie and Clyde and 1969’s Easy Rider to connect American filmmaking with the larger convulsions shaking the Anglo-American world. The director who most electrified English-language cinema, Sragow says, was Richard Lester, the Philadelphia-born director who moved to England and worked with oddballs Peter Sellers and Spike Milligan before directing A Hard Day’s Night (1964). Lester would push Anglo-American cinema out of its theater-based origins and into a witty, kinetic style that owed more to television, art photography, and the irreverent energy of rock bands like the Beatles. In 1966, he made A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, based on a Sondheim musical and featuring Buster Keaton (!) in his last film role. (Lester would go on to make the classic Superman II and the less triumphant III.)

1966 also left a mark on literature. Confessional poetry was running out of steam — Anne Sexton would win a Pulitzer for her anguished Live or Die, one of the movement’s last highlights. Frank O’Hara was killed on Fire Island. But Russian poet Joseph Brodsky came out of Arctic exile, while Belfast-Irish poet Seamus Heaney published his first book, Death of a Naturalist; Major careers and Nobel laurels awaited both writers, though it was not immediately obvious where poetry was going. The novel was, likewise, at a turning point: 1966 would see the publication of both Jacqueline Susann’s best-selling chronicle of drugs and ennui, Valley of the Dolls, and Thomas Pynchon’s gnomic postmodern classic The Crying of Lot 49. Appropriately, French theorist Jacques Derrida would make his beachhead in the United States with a speech at Johns Hopkins — on a new way of looking at language and literature — that would transform the field for decades.

One of the year’s most revolutionary books was not traditionally literary at all, but a (purportedly) journalistic chronicle of a brutal Kansas murder. Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, says Gene Seymour, a culture critic for Bookforum and The Nation who devoured the book as a kid, captured “the strange kind of forces being unleashed in that era.”

For Seymour, an African-American teenager growing up in not-terribly-posh Hartford, Connecticut, the key cultural artifacts of 1966 were Star Trek, with its optimistic vision of a multiracial future, and Bill Cosby’s comedy album Wonderfulness, with a title inspired by the comedian’s pioneering television show I Spy. Seymour reflects, as if offering a painful confession, “Everything I know about how to tell stories and write narrative I learned from Bill Cosby,” whose style paralleled the jazz solos the writer loved. “Withholding information, using his voice to get into a rhythm and tempo of storytelling.”

Overall, it was a strange time in which reality and fiction got in each other’s way. One night a space probe nearly blew up, Seymour recalls, and its troubles pre-empted an episode of Lost in Space.

And some of the era’s icons looked very different when viewed without a middle-class white lens. “As far as a lot of them were concerned,” Seymour says of fellow working-class blacks, “Dylan was just this strange white boy with a lot of cultural capital.”

And 1966 was a great year for jazz, with eerie recordings by vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson and the last gasp of the acoustic Miles Davis Quintet before the trumpeter helped invent jazz fusion.

“The scientific breakthroughs and art and the political progress all seemed joined,” Seymour says. “They were part of the kind of dynamic energy.”

¤

For reasons likely connected to its publication by a British house and its emphasis on life in the United Kingdom, Savage’s 1966 can be hard to find in the States. Some of its references will be lost to readers who don’t own all the Beatles albums on mono or read Mojo magazine. Visibility and obscurity aside, the book is a marvel, easily the match of Savage’s celebrated punk chronicle England’s Dreaming.

“People think that a critical and rebellious youth culture began with hippies and the underground press in 1967,” Savage writes in the book’s introduction.

In the music press from 1966 […] almost all the ideas and attitudes that would define the remaining years of the decade are in place: the Love generations, opposition to the Vietnam war, critiques of youth consumerism, an alternative society, a new world as yet unmade.

The book proceeds month by month, with January devoted primarily to anxiety over nuclear weapons, April to acid, May to the feminine mystique, July to Tamla/Motown, and so on. Savage is building a narrative, using each month and each new 33 RPM single as part of a larger story. It works brilliantly, most of the time, but also leads to the book’s one serious flaw, as it skids past what turned into a brilliant and horrible year for Bob Dylan. Savage writes eloquently about the Beach Boys’s Pet Sounds, the Beatles’s Revolver, the Rolling Stones’s Aftermath, the first two albums of Arthur Lee’s visionary group Love, and many singles — he loves the concision of 45s — but Dylan’s epochal two-LP Blonde on Blonde almost gets lost.

1966 saw a controversial, celebrated spring tour by Dylan and the Hawks (famous for the taunt of “Judas!” at the show in Manchester, England), the May release of what may be the finest rock album by an American, and the July motorcycle crash that led to a period of withdrawal and silence and mystery. Whether you agree with the Nobel committee or Columbia Records, which recently released 36 discs from the ’66 tour, this was a consequential moment for the most visionary and accomplished solo artist in all of rock music. Savage told me that Blonde on Blonde didn’t fit cleanly into his narrative, and that other scribes have written extensively about Dylan. Certainly so, but it’s a lost opportunity for a writer who can make even the Beatles or the Velvet Underground and Warhol sound fresh.

One of the book’s great strengths is the way it finds lively historical details, or fresh context, even on well-trod ground. Pleasantly dense and beautifully textured, 1966 is like an album by a great band not often enough heard from, with all the filler removed. It belongs on the shelf not just with the rock chronicles of Greil Marcus but between David Kynaston’s social history Austerity Britain and Eric Hobsbawm’s peerless quartet on the 19th and 20th centuries.

One of the startling things about Savage’s tale is the role of the Beatles. Even casual fans are familiar with the image of the deeper, more serious, pot-smoking band of Help!, Rubber Soul, and after. “The Beatles give rocket fuel to the ’60s youth culture, in terms of money, ambition, fashion, and prestige,” Savage tells me. “Suddenly everything became really intense.”

But the bitter irony and despair within the most popular and inventive group of the era — the one that inspired and intimidated bands from London (the Stones among them) to Los Angeles (the Beach Boys, the Byrds) and released, in August, what may be the greatest rock album of all time — is still breathtaking. As the year began to tatter near the end, and with counterculture heroes like Dylan and Jagger out of the picture, some looked to the lads with a kind of “waiting for Godot” expectation.

Yet ’66 was the year that the Fabs stopped touring; McCartney — the band’s diplomat and optimist — talked about the pointlessness of playing live. Lennon was clearly tired of being in the band and said he was more interested in making films or painting. Harrison — “the quiet Beatle” — was the most sardonic of all. “If we do slip, so what?” he told the journalist Maureen Cleave. “Who cares? We’ll be just where we were, only richer. Being a Beatle isn’t the living end.”

Savage, who is gay, includes a chapter on the British “homophile” movement, which was much less about scenes, styles, subcultural magazines, and marches, and much more about legislation. By the end of 1966, Parliament was turning, and repressive laws against same-sex love were on their way out; the struggle would continue far longer in much of the United States.

¤

By the year’s last days, it was snowing in Scotland and England’s north. A nation that loved black music and artistic experimentation saw a young Jimi Hendrix arrive in London, release “Hey Joe,” his first single, and bring several of the day’s tendencies together in blazing fashion. The term “psychedelic” began to be used in the press, the club UFO had just opened and hosted a show by Pink Floyd, and a televised adaptation of Lewis Carroll transposed his animals into human beings and became known as Alice in Psycholand.

Welsh crooner Tom Jones’s “Green, Green Grass of Home” was number one in the United Kingdom, the best-selling album was the soundtrack to The Sound of Music, and the highest-selling single in the States was Army Sergeant Barry Sadler’s “Ballad of the Green Berets.” The Evening Standard described 1966 as “The Year Pop Went Flat.”

Everything had changed. “Everybody can go around in England with long hair a bit,” John Lennon said, “and boys can wear flowered trousers and flowered shirts and things like that, but there’s still the same old nonsense going on. It’s just that we’re all dressed up a bit different.” So nothing had really changed. Or had it?

Savage, who’s as fed up with Boomer nostalgia as any Gen X-er, still thinks the era marked real progress, and that 1966 was both a peak and an inauguration of a half-century of freedom. Its flowering led to more tolerance, more openness, and to a year — 1970 — that he considers perhaps the musical summit of all time. (Savage has built epic CD compilations of songs from various years and local scenes.)

So 1966, with its political, cultural, and social shifts, accomplished something lively and real. Savage calls it the apogee of a kind of capitalist-democratic hedonism based on creativity and pleasure. But the author — who is flirting with Irish citizenship post-Brexit vote — is no longer so sanguine.

“That idea, which is American, and dates to the end of the Second World War, is now under threat,” he says. “The UK and America have so overdrawn on that particular bank.” And the Anglo-American world will not be saved by merely waxing nostalgic for the high ’60s or the welfare state that’s lasted for seven decades.

“We can’t go back to 1966,” Savage says by email, “but a proper understanding of that year tells us what was at stake and what people were fighting for. It wasn’t just a golden Austin Powers pop age. The Second World War reconstruction is over. It’s flipped. Germany is the good guy in 2017. Time to look forward to the way society can be organised in future.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Scott Timberg is the editor of The Misread City: New Literary Los Angeles and author of Culture Crash: The Killing of the Creative Class, an examination of the damages to our cultural landscape wrought by recent technological and economic shifts and an argument for a more equitable and navigable future. Timberg is writing a book called Beeswing: Britain, Folk Rock, and the End of the 60s with the guitarist Richard Thompson.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Dreaming the Beatles: An Interview with Rob Sheffield

Scott Timberg interviews Rob Sheffield about his new book, “Dreaming the Beatles: The Love Story of One Band and the Whole World.”

Greil Marcus on Bob Dylan’s Nobel Prize

Is it literature: who cares?

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!