Foregone Conclusion: The Afterword as Preface

Darrell Spencer considers death through the lenses of golf and Robert Altman’s “McCabe and Mrs. Miller.”

By Darrell SpencerSeptember 4, 2022

[Y]our death is not the end of your body. The chemical bonds that held you together at the molecular level continue to break in the minutes and months after you die. Tissues oxidize and decay, like a banana ripening. The energy that once animated the body doesn’t stop: it transforms. Decay from one angle, growth from another.

Unfettered, the decay process continues until all that was your body becomes something else, living on in others — in the grass and trees that grow from where you might come to rest, and from the critters who eat there. Your very genes, little packets of stuff, will live indefinitely as long as they [find] someone new to host them. Even after interment or cremation, your atoms remain intact and scatter to become other things, just as they pre-existed you and became you.— Dr. BJ Miller, “What Is Death?” The New York Times, Sunday, December 20, 2020

GOLF, DEATH, AND Robert Altman’s film McCabe and Mrs. Miller, a concoction, a Mulligan stew I have set out to poke around in. Not to maunder. Please, no.

By death I mean mine.

It’s a long story.

Life. That is, it can be.

There are people who believe that the atoms of the dead end up as part of us. A woman in England swears she is partly Sylvia Plath. I have a pal who believes he is partly Marlon Brando. He is thinking left leg mostly.

When I taught literature at the university, I covered blackboards in chalk. To do so was an act of art for me. I often got lost, my work suffering from destinerrance (Derrida), a wandering, my point retreating, a feeling of being alive, of soft-shoeing until I picked up a thread and tap-danced. My class notes, my quarrel with myself, in multicolored ink and scattered helter-skelter on legal pads, (mis)led me to the point where I found myself flummoxed, to where I straddled the horns of various dilemmas; my endgame (which would become my opening the next day) to begin classes at that crossroads. I didn’t want to go in with answers. After discussions, I often snapped photos of the blackboard (first with cameras, then an iPhone) so I would/could remember what we had said. Students could/would teach me things I had never imagined. Our discussions were my way of dancing. I wallowed in chalk and breathed deeply its dust, its dryness. I left class with chalk streaks on my jacket that I swiped at. The taste of chalk was in my mouth as comforting as the smell of cigarette smoke from a neighbor’s backyard. Chalk made me sneeze. On blackboards I illustrated life this way:

A former student from my time at Ohio University writes me a letter every five years or so. He includes his own rendition of my life drawing. He marks where he is in his life. It is delightful to hear from him and to see his drawings. In my heart I always wish him the best and the joy he deserves. The X below marks his marriage after his return from Japan:

The problem here is that any attempt to “show or illustrate or even talk about death” fails. You can’t say anything that is true. Our atoms find a home. Sure. I suppose so. An old saw is that we can describe our dying but not our death. Isn’t that what is frightening: no one has experienced it? Death is like ________________________. Comparisons lie. Even white space lies. Even a period would be disingenuous. Brackets suggest closure.

It’s a good bet that most of us don’t want to die. There are exceptions, of course. There is hurt that overwhelms. See Camus: the worm is in the heart of us. Some people choose to die. Larry Levis explains one possibility in his poem “Elegy with a Thimbleful of Water in the Cage.” His friend Stavros, holding forth “at the Café Midi, / In the old Tower Theatre District,” retells the myth of the Sibyl. Levis/Stavros explains what happened “[t]o the Sibyl at Cumae after Ovid had told her story.” We have heard the myth. She made a mistake; she forgot to ask for eternal youth before she accepted the gift of eternal life. So, as Levis tells us, as Stavros told it,

As […] the centuries passed, she finally

Became so tiny they had to put her into a jar, at which point

Petronius lost track of her, lost interest in her,

And at which point she began to suffocate

In the jar, suffocate without being able to die, until, finally,

A Phoenician sailor slipped the gray piece of pottery —

Its hue like an overcast sky & revealing even less —

Into his pocket, & sold it on the docks at Piraeus to a shop owner

Who, hearing her gasp, placed her in a birdcage

In Levis/Stavros’s account, the Sibyl withers and shrinks until the boys of the docks who pass her by, who press their ears against her cage, no longer stop to ask what she wants. Her cry is her anguish: “I want to die.” Until:

[O]ne day the voice became too faint, no one could hear it,

And after that they stopped telling

The story. And then it wasn’t a story, it was only an empty cage

That hung outside a shop among the increasing

Noise of traffic

The aging Sibyl begs to die. I am 74, and I get it. Even if I shout, no one hears or listens to me. Not seriously. But lesson learned: before you accept any offer of eternal life, don’t get antsy and forget to ask for eternal life without aging. I would suggest that if the Sibyl had asked for eternal youth, that too would have been a mistake. Borges said: “How else can one threaten, other than with death? The interesting, the original thing, would be to threaten someone with immortality.”

One more digression, then on to golf — I promise — and death.

And Altman’s film.

There is sadly the recognition that if you did live forever, and even if you didn’t age (asked for eternal youth), and you saw everything there is to see, and you did everything there is to do — say, you make that 50-foot downhill triple-breaking putt on the 18th green of the toughest course you play in full view of the clubhouse, say, if you made that shot over and over and over again for the club championship, you would eventually beg for death. Joy dies. Over and over and over, day after day, year after year, century after century (until, as my dog Teddy says, Andromeda bumps into the Milky Way) … You would want to miss the putt eventually. You would plead to miss. You would invent a game that involved missing. Say you had sex with that one person you most desire, the one person you wish most to touch, as vividly as a vivid dream … over and over and over, day after day …

Let’s stipulate the necessity of death.

As if we could do otherwise.

So: I wish to tell the story of the death I want.

Hold on, just one more second.

I have always thought that when my time came, I would choose my Uncle Clark’s death. He taught high school English, and he directed school plays. He loved movies; his favorite was Dead Poets Society. From what I have read online and from what I have heard at get-togethers, my uncle (family called him Uncle Stuck) was the type of teacher Robin Williams portrays in the movie. Irreverent and bright and curious and brilliant, Clark opened minds. He freed spirits. So Uncle Clark and his friend Mary Phoenix went to see Dead Poets Society. They grabbed a meal on the way home. Clark died in his sleep that night. I see him lying in bed, reading Elmore Leonard or Time, a Kool in an ashtray balanced on his bedsheets, a mason jar filled with ice and Tab on his nightstand. He was only 62.

He slept; he didn’t wake up.

God, can you imagine? I mean you don’t wake up in darkness; you don’t wake up in sunlight. Your waking is neither black or white. You don’t wake up sad or anxious or joyful or ready to learn to play the guitar. The mole of your left cheek remains but you don’t see it. You. Don’t. Wake. Up. (I hate morning and I hate nature. But. Still.) You don’t exist to be aware of the fact that you don’t exist. God, can you even guess at how heart-pounding that would be, could be? But, of course, to do so wouldn’t be heart-pounding or otherwise. There is no word for what it would be. You won’t be frightened; you won’t be thrilled. You won’t exist to know you don’t exist. My friend, who was looking forward to dying, said, “No more flat tires on the freeway.” Another friend woke up to a sore shoulder. He died six weeks later. A lover killed herself. (Read Leonard Michaels on this horror, in Sylvia.)

People pretend to be blind. Therapists put people through empathy exercises. You can’t pretend to be blind. You are not blind. You are alive, and you are pretending that you can’t see, but you can.

I am not sure who determined the cause of death for Clark, but his sister, my mother, was told his heart failed. His body stopped — his diet, his drinking, his smoking. Our cousin, who found him, who had to climb through a window (his doors were locked, his doors were never locked) to get into his house, claims he was murdered. Her evidence: 1. The locked doors. (He never locked his doors.) 2. His special-order pool cue was gone. (Turns out she took it.) 3. The bed had been made up around him in a military way. 4. No burn to the filter Kool. 5. No Tab. 6. No dog-eared Elmore Leonard. She cited a long list of evidence. The family ignored her.

One more sidetrack, a short one.

There’s a scene in Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain in which Paul Newman kills a government agent who is on his and Julie Andrews’s trail in East Germany. The period is the Cold War. The film depicts the killing slowly and brutally. Records all of grumbling of a struggle, and the stumbling into furniture, the knocking about of dishes. Their fight is as awkward as wrestling can be even at its most balletistic. Is full of grunt. Hitchcock claimed that the scene shows how hard it is to kill a man.

It doesn’t. The scene shows how hard it is to film a scene about killing someone.

The scene is grudging.

I don’t like the movie. But then I think Hitchcock is overrated. He was an ass in his life, and he is/was a cheesy filmmaker.

Not that he would have cared what I think.

Apologies, a second of maundering.

Which leads me to another movie.

I want to write about dying in Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller, about the murder of the young cowboy. His death is the death I want. Not that I want to be gunned down. Not to be murdered. Not to be killed by a gunslinger named the Kid. Roger Ebert called the cowboy’s dying “one of the most affecting and powerful deaths there ever has been in a Western.”

I will explain my wish.

Place/Time

Let’s get any mystery out of the way, the denouement. I want to die on The Ledges golf course here in St. George, Utah. I played golf as a kid growing up in Las Vegas. Then I quit for 47 years. I want to die on the 7th hole of The Ledges. It is a par 5. I think it is close to 500 yards long from the white tees (where the old guys hang out).

The day I want to die is the day I score an eagle on the hole.

Desert flanks the 7th fairway on its left. Coyotes cruise the sagebrush. One day one hesitated and looked over its shoulder at me. I don’t mean to sound like drama itself, but I felt, on a 90-degree day, a chill. I was looking at ice-cold indifference, at the unfathomable. I described a coyote I saw in a Nevada basin, saw it as hungry enough that, as it trotted up a hillside, the coyote ducked toward its thigh, took a bite, and chewed sinew and tendon down. Another day I spotted a fox in the brush near the 7th of The Ledges, a hole which is laid out on an open section of the course, and, as they say on TV, it fits the (my) eye. The fairway is a football field wide and sweeps drives to the left off the tee at about 200 yards. You aim at a bunker and try for a small draw.

So the day I die I nail my drive; I hit it flush. It starts at the middle of the bunker, turns like a well-flung fishing line (confession: I don’t really know fishing), and finds the fairway where it catches the slope and rolls about 30 yards, slowly following a curving line but stopping short of the rough. In Five Lessons: The Modern Fundamentals of Golf, Ben Hogan describes how the perfect drive feels:

One of the greatest pleasures in golf — I can think of nothing that truly compares with it unless it is watching a well-played shot streak for the flag — is the sensation a golfer experiences at the instant he contacts the ball flush and correctly. He always knows when he does, for then and only then does a distinctive “sweet feeling” sweep straight up the shaft from the clubhead and surge through his arms and his whole frame.

That “sweet feeling” is all we need, whatever it is we do — paint, dance, clerk, run, limp, lawyer, swim, sweep corridors, fish, on and on. If you have played golf, fill in the blank, describe your “sweet feeling”: _____________________________________. Even if you play badly most days, my bet is you have hit one perfect shot. Your shot to die for: I know (picture me red-faced, chagrined) — that was cheesy.

Still, it is my day.

McCabe and Mrs. Miller

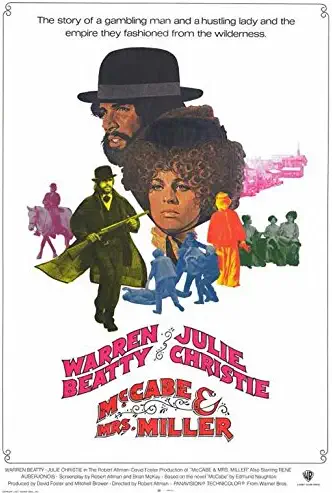

Robert Altman filmed McCabe and Mrs. Miller in Canada. Andrew Sarris, in The Village Voice, wrote: “McCabe succeeds almost in spite of itself, with a rousing finale that is less symbolic summation than poetic evocation of the fierce loneliness in American life.” The movie is a revisionist western set in 1902 in Washington state. One of the film’s “throwaway moments” occurs when the Kid guns down a young cowboy.

The Cowboy dies on a footbridge in the town of Presbyterian Church. He rode a far distance for the pleasures of the flesh; Presbyterian Church offers the finest brothel in the West. Pudgy McCabe financed it; Mrs. Miller runs it. The Cowboy spends his entire visit in the whorehouse. He dances. He sings. He whores. He stays a week, and when he leaves, the women gather to give him a small sendoff. He is all grin. He heads out of town, but he needs to pick up socks at Sheehan’s Saloon. He wore holes in all his socks scooting from prostitute to prostitute. The movie set, the town itself, legend has it, was built around the shooting of the movie. Presbyterian Church begins as an up-and-coming, unfinished mining town. Buildings go up; the story moves on and through and around their construction. It is winter when the Cowboy is shot.

I want to die at the height of spring.

Not winter.

By the way, I hate cowboys and their ilk. Even the good ones. For personal reasons.

Lighting

In his article in Robert Altman: Interviews, “The 15th Man Who Was Asked to Direct M*A*S*H (and Did) Makes a Peculiar Western,” Aljean Harmetz describes the lighting in McCabe and Mrs. Miller:

The faded quality of the color is Altman’s deliberate attempt — by methods known as flashing and fogging — to create the archaic feel of an old photograph left for too many years in somebody’s attic album.

Except for the snow sequence at the end of the film where he wanted to increase the reality of “the moment of truth” with as harsh a black-and-white effect as possible, Altman used fog filters throughout the picture. Then, before the negative was developed, the film was put on a printer and re-exposed to light. According to Altman, “adding more yellow than normal not only threw the film toward yellow but made the look of the film more extreme. Adding more blue did the same thing.” Altman’s intention was “to complement the period, the set, and the look of the people, to make the audience see the film as more real.” To him the blue and yellow suggested the faded printed material of the period — old magazine and bottle labels, aging and yellowed newspapers.

I hope to die in a gloaming, late in the day, dusk; it has to be spring, as I said. I could relax my requirements and accept early summer. (The summer sun in St. George, Utah, intense and unrelenting, mean as a fist, can overwhelm you when you look into it.) Gloaming may be the wrong word; gloaming doesn’t really give me enough daylight to finish the round. I know that doesn’t make sense. I will be dead. But. Still. Gloaming-like will do. Let’s say more to the point: I want to die in Altman’s flashing and fogging. I want it to be Altman’s colors that fade as I pass. I want to be alone; I love playing golf alone. My favorite time of day:

A poetic word for “twilight,” or the time of day immediately after the sun sets, is gloaming. The best thing about summer evenings is looking for twinkling fireflies in the gloaming. That romantic time of day when the light has mostly faded but it’s not quite dark yet? You can call that the gloaming.

I once awoke in the gloaming in the bed of a woman I loved. Next door, a chapel, close by in the tight neighborhood, its windows open, and a choir singing: “All Creatures of Our God and King.”

I could have died at that moment.

There was another event in a gloaming. I am on the patio of a second-floor apartment in Los Angeles. I cannot tell you how I got here; I had begun celebrating the night before in Las Vegas. Inside is a woman and her baby. I don’t know them. The apartments sit at the bottom of a hill; the building is surrounded by palm trees. There is an intersection, and it supports a traffic light. Down the steep hill comes a squadron of Shriners; all of them wear brocade-festooned fezzes. They ride minibikes, their knees up around their ears. The light turns red on them, and they charge wild-eyed on through. They are beside themselves in the thrill of it.

I wouldn’t have minded if I had died then.

It is the dead of winter when the Kid kills the Cowboy. The Kid murders him. His dying is a result of bad timing. That is, 10 minutes earlier or 10 minutes later, maybe in another movie, the Cowboy would have crossed the footbridge at Sheehan’s, had a drink, bought his socks, suffered some jocular joshing about his time in the brothel, recrossed the footbridge, mounted his horse, and ridden off into the sunset. He would have gotten home instead of being a bit of noise in a film. Instead, the Kid, the gunfighter, guns him down. I would like to say he provoked the Cowboy, but the Cowboy didn’t even see it coming. The Cowboy wouldn’t have recognized a provocation if it bit him on the butt. You must remember that the Cowboy suffers from youth and optimism. He is cordial. He has ridden a long distance to Presbyterian Church because he heard about the brothel. Warren Beatty’s character, Pudgy McCabe, meets him first; McCabe confronts the Cowboy, believing the mining company has sent him to kill McCabe. The Cowboy clarifies the situation: he has come because he heard the town has the fanciest whorehouse in the territory. He says to McCabe, “Gee, it’s been so long since I had a piece of ass.” (Can you imagine gee and piece of ass abiding each other’s company in any other sentence?) He spends his entire visit with the ladies. He declares that it doesn’t matter who is first among the prostitutes; he is going to have them all. Robert T. Self, in his Robert Altman’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller, describes the Cowboy’s death as one of the film’s “minor stories [that] run parallel and peripherally to the dominant stories of the film,” as part of Altman’s “strategy of indirection,” but then Self works to rescue these “apparently gratuitous moment[s]”; that is, he explains them — he gives them meaning. He is, after all, a critic. Self commits various readings, and they are intriguing and informative. He is smart. He cites, for example, Peter Lehman’s theory that the Cowboy’s death stands as “a crisis of shortness in Altman’s films, routinely and perhaps most notably represented here in reference to a small penis size.” The prostitutes, in whispers and giggles, do mock the size of the Cowboy’s penis. Thus, an interpretation of McCabe and Mrs. Miller saves even its minor moments.

Self brings other readings to the text. I read them — stuff about masculinity, about women as the sisters of mercy (you can hear Leonard Cohen’s soundtrack), and others, which you can guess at, such as the civilization versus the West, such as manifest destiny — and I thought of Sontag’s claim that “interpretation is the revenge […] of the intellect upon the world.”

To interpret is to satisfy.

Our itch for clarity.

Our desire for closure.

Our thirst for meaning.

Not to mention our birth cry for answers.

Moby Dick is about the danger of a monomaniacal obsession. Okay. Put the book on the shelf.

I will die as part of a story. A friend will tell it. My wife might. (He died with a Cheetos bag in his hand.) A stranger. A former student. I don’t want to be part of someone else’s narrative. I don’t want to be part of someone else’s interpretation. So many critics have said that to tell a story is to mistell it. Traduttore, traditore: translator, traitor.

I don’t want to be betrayed thusly.

Golf, Death

Let me continue my golf story (and betray myself): this is a retelling: I stand over my second shot; (back at the ranch) we left me about 250 or 260 from the green. My ball had come to rest on the left side of the fairway. The Ledges is in terrific shape. I can’t reach the green; I plan a layup. I pull my three wood, ease the cover off (Kate cut and trimmed the cover to look like Teddy, our cocker spaniel), ease through a couple of practice swings, and a breath. The goal is to hit the ball toward the right side of the fairway and watch it settle its flight and take the slope and swing down into the middle. I make solid contact. The ball sails over the post that marks 150 yards to the center of green; it lifts somewhat. It hits, but doesn’t catch the slope. It stops about a foot into the rough. Disappointed, but I am less than 80 yards from the pin.

The green, massive to my thinking, slopes sharply — 30 degrees? — toward the desert. You can’t determine that slant clearly from the fairway, but you can feel the downhill when you stand on the green.

McCabe and Mrs. Miller

The Cowboy, shot twice, falls from the footbridge into the partly frozen pond of Sheehan’s Saloon and Hotel. His body breaks up ice; he bobs in the water. The water is filthy, looks muddy. Altman films the killing from behind, from above, and in a kind of jerky stop and go. You see the smoke rise from the Kid’s gun. The two shots echo.

I don’t want to die in slow motion.

I definitely don’t want to see my life pass before me. Who needs the punishment?

I definitely don’t want to die anywhere near ice. I hate cold. When my wife travels, I put the thermostat on 78. I grew up in Las Vegas. I want to cash my chips in (sorry) in heat. Summer, you can’t walk barefoot on the streets in Las Vegas. I like that condition of the city. You can fry eggs on the sidewalks. I have done so. Maybe I should move my death from spring to summer. Also, gloaming, by definition, as I said, is too late in the day; I don’t intend to finish the round but I do want the chance to complete it. Gloaming in summer lasts longer.

Music and Soundtrack

I suppose, as a poet, among my fears can be counted the deep-seated uneasiness that one day it will be revealed that I consecrated my life to an imbecility. Part of what I mean — what I think I mean — by “imbecility” is something intrinsically unnecessary and superfluous and thereby unintentionally cruel.

— Mary Ruefle, “On Fear”

McCabe and Mrs. Miller begins: the arrival of a traveler to the new town, Leonard Cohen’s “The Stranger Song” supporting his journey. Warren Beatty rides into Presbyterian Church. His horse is white-gray, and he leads a mule. Cohen sings,

Like any dealer he was watching for the card

That is so high and wild

He’ll never need to deal another.

Odd music for a golf course, but so is my thinking here as I talk about the death I want. Golf can be a pleasure; it is a game and can be fun. Yes, it is trivial; it is an imbecility. No point in getting moody about a round. Golf ought to be enjoyable. Still, Cohen’s voice and music, as Altman has said, “fitted [the picture] like a glove.” Altman was shooting That Cold Day in the Park in Vancouver and living in a house with his editor Danny Greene and Brian McKay, an assistant, when he first heard Cohen’s music, Altman says.

The first Leonard Cohen album had come out, and I was just crazy about it. We’d come home in the rain to eat dinner, and we’d put that record on so often we wore out two copies! We’d just get stoned and play that stuff. Then I forgot all about it through the next movies. When I walked into that apartment [where Altman was visiting a friend in Paris, where he went to a party] and heard that music, I said, “Shit, that’s my movie!” So I called the editor, Lou Lombardo, and said, “Get hold of the Leonard Cohen album, transfer all those songs, and I’ll be back in a couple of days.”

Altman adds: “I put in about ten of them at first — of course, we way overdid it — and then we ended up with the three songs that were finally used, and I thought they were just wonderful. I think that’s a pretty accurate and truthful story.”

Cohen sings to lessen his and our misery; you wish to tell him that nothing is as bad as he makes it sound. You think: he has lost and lost and lost. He talks on stage, and he is funny, he is sardonic, his wit is dry. He has lost, and he has lost, and he has lost, and he has come out the other side. He stands on his feet.

You hear his joy and sorrow in his lyrics and particularly in his voice.

Life sandbagged him. He sandbagged himself. Yet he is on his feet, and he is singing. Cohen plays in my head too often on golf courses,

Oh the sisters of mercy, they are not departed or gone.

They were waiting for me when I thought that I just can’t go on,

And they brought me their comfort and later they brought me this song

Oh I hope you run into them, you who’ve been traveling so long.

Such generosity: He is wishing us well.

When I left they were sleeping, I hope you run into them soon.

My wife, Kate, and I lived in a casita on Rancho Circle in Las Vegas. The casita had a living/sleeping room, a small kitchenette, and a bathroom. It was tiny and square. We had married the week before; I had apprenticed as a sign painter. I worked from six in the morning until three or four in the afternoon. Then I did scab work painting signs after I clocked out and on weekends. Rancho Circle was a wealthy area in town. The owners of the house we lived behind were friends of my parents.

One day I was home with our three dogs. I put Leonard Cohen on the record player (this was early 1970s). It was a weekend. Mr. Ashworth, owner of the house, came by. I didn’t hear him knock, had Cohen turned up loud and he was singing “Suzanne.” Mr. Ashworth stepped in and surprised me. We talked for a while, about my job, about our future. It seemed like a fine visit. Nothing much going on. I hadn’t thought to turn the music off. That night I got a call from my dad. He expressed his concern about me. Why? Because his friend, Mr. Ashworth, had phoned to tell my mother and father that he was worried I was in a dark place. Because the music I was listening to was morbid, was sad, was depressing, was part of the devil’s mix. He and my father knew each other from church.

Surprised me. I thought I was happy.

Suzanne takes you down to her place near the river

You can hear the boats go by, you can spend the night beside her

And you know that she’s half crazy but that’s why you want to be there

And she feeds you tea and oranges that come all the way from China

And “Winter Lady”:

Traveling lady, stay awhile

Until the night is over

I’m just a station on your way

I know I am not your lover

Cohen’s lyrics have become part of life’s soundtrack for me.

Cohen: yearning: for: what?

For Godot to arrive.

And there is the dialogue of McCabe and Mrs. Miller.

Mitchell Zuckoff, in his Robert Altman: The Oral Biography, quotes Julie Christie who describes the Altman sound: “I know that the sound is on top of other sound, all multilayered. […] Robert was into creating more of a tapestry sound. It never mattered what anybody said. It gets the atmosphere. So when you’re in a bar you really get it.” He also cites Joan Tewkesbury: “Warren [Beatty] was used to clean, Hollywood sound, and Bob [Altman] was encouraging a mess.”

I want to die while the mess that is my mind is still sluicing and juicing synaptic junctures like firecrackers. While I can’t stick to the subject. While golf is and isn’t the issue. While I digress. Vilmos Zsigmond describes Altman’s approach:

The sound track was very very courageous because he deliberately made the sound so too many people are talking at the same time. […]

He recorded on sixteen tracks. He needed the separation of the tracks, because in the mixing stage, he could actually bring one forward and leave the others in the back. So he would select which voice should be dominating and the other ones secondary.

I want to die on the seventh green at The Ledges, and I hope that the cacophony of voices in my head is firing — the pissed off me, the me who feels joy at the sight of squirrels circling a tree trunk, the me who fears and delights in coyotes, the one who became friends with the fox that visited the fifth hole at the Ohio University nine-hole course, the devastated me, the runner who can’t coexist if I don’t run at least five miles, the me who loses it and laughs uncontrollably, the me who wept (howled) one night for no reason I could explain (alone and alone), empty, the me who delights in the faded and soft green walls that I grew up with in Las Vegas, and the me whose knees buckle at the beauty of neon, not to mention the me who drove a purple Renault sedan in high school (purple shag carpet in the back window well) — 16 tracks of me. When I taught at the university, I would start to make a point (a short story will fail unless it suffers from fracturing), imagine an objection (a house divided against itself will fall), remember a passage I heard or read (Guy Davenport: “A work of art is a form that articulates forces, making them intelligible”), which takes me to the first time I, as a sign painter, stole a bucket of paint and felt guilty.

I am too distracted to be a good golfer.

I am distracted. Or so they say.

Too many people talking.

Might it be possible to be too distracted to die.

Plot and Character

Plot is people. But it is never other people.

— Stanley Elkin

I am not sure I understand what Elkin is suggesting. He tries to clarify his thoughts in an interview with Peter J. Bailey: “What I guess I meant is that plot is […] never people. There’s got to be that focus on one guy. It’s the agenda of a single man or woman.”

I can see how agenda might be discussed as plot (I want this; you can’t have it — resistance, obstacles, monsters to overcome, a journey to take …), but an agenda seems to me to be aleatory, less cause-and-effect.

I like the idea of agenda. Like, maybe: wanting to hole out from 80 yards. That’s an agenda, and there are obstacles to my doing so: what talent I have, the rough, the air itself, the design (and designer) of the hole. The designer sets out to challenge me. To make my task risky but possible. To encourage me toward perfection.

Plots plot against you. Of course, plot is “the end” haunting the beginning — is the end haunting the entire narrative. The young cowboy is part of the story of McCabe and Mrs. Miller. He must, therefore, according to Hoyle, contribute to the plot. He can’t not die. Cause: McCabe came to Presbyterian church. Or, first, Presbyterian Church didn’t have whores, so McCabe came. Or, McCabe earned (gambling) a sum of cash and wanted more (greed, his sin?), so … This tracing (search for) cause and effect is a form of foolishness. It is endless; it diverges endlessly. As good as anything: The Cowboy has come to Presbyterian Church to enjoy the pleasures of the brothel McCabe and Mrs. Miller built and developed, the finest in the Northwest.

The Cowboy finishes his business. He satiates his desires. He fills his tank. He is a happy-go-lucky dude.

He must get back to the ranch from which he came. His socks are holey. He stops at Sheehan’s to buy socks.

As a result:

He dies.

His death foreshadows McCabe’s death at the end of the movie? That’s one interpretation. As good as any. I don’t think so unless we are only about interpretation of narrative.

Unless you are only about closure. Which is death.

More to my point is that I don’t want to be “part of the plot.” The Cowboy is. He is a member of the stream of the effect of a cause. That is plot’s plan, no matter how complex the plot may be. A cause becomes an effect which is then the cause (another cause in the chain, in the trudge up the hill toward climax). The Cowboy dies because he is the shadow of the archetypal Goofy; that is, he is simple-minded and all about fun. There is a lesson to learn in the plot: you can’t live as a grasshopper.

I don’t want to be a lesson.

Grace Paley’s character (Paley as herself fictionalized by herself; that is, written up) in “A Conversation with My Father” tells a story to her dying father; he complains: “With you, it’s all a joke.” His criticism is that she has left everything out.

Which is the long view: it’s all a joke.

A joke we will not hear to laugh at.

The narrator retells the story. She provides more details; she leaves her character at home alone, having “burst into terrible, face-scarring, time-consuming tears. The End.” Her father is pleased; he is satisfied. The story fulfills his desire: it tells the story of “the end of a person.” The daughter claims he is wrong, that the woman is “only forty. She could be a hundred different things in this world as time goes on.” His response, his disappointment: “Jokes,” he said. “As a writer that is your main trouble. You don’t want to recognize it. Tragedy! Plain tragedy! Historical tragedy! No hope. The End.” He desires to convince his daughter that life ends in tragedy. His daughter will eventually have to face that fact: no hope. The end. In Ronald Schleifer’s “Grace Paley: Chaste Compactness,” Schleifer describes Paley’s fiction variously as “articulation of experience,” as concerned for the “ongoingness of the surface of things”; he claims that Paley’s fiction is “illegitimate,” as “discursive [in its] practice,” as “a form of listening.” He argues that Paley’s fiction escapes its own form; one aspect of that form would be plot. The daughter in “A Conversation with My Father” responds to her father’s wish for a simple story that carries its characters through cause-and-effect to an end. He wants a story that follows a “plot, the absolute line between two points, which I’ve always despised. Not for literary reasons, but because it takes all hope away. Everyone, real or invented, deserves the open destiny of life.”

I would not mind dying as an articulation.

So Cowboy, high on his time in the brothel, stands at the far end of the footbridge, and we know he is going to die. His death is the death of Goofy. The Cowboy is all boyishness and grin and innocence. (You know that phrase: fuck your brains out. Maybe that is his mistake, is the cause in this plot.) He steps onto the bridge and says to the Kid, “Hold it, Sonny, I don’t want to get shot.” The Kid, sent by the Harrison Shaughnessy Mining Company, is one of the three killers who have come to town in response to McCabe’s refusal to sell his holdings in Presbyterian Church. The Kid is shooting at a whiskey jug afloat in the pond. He misses it, he claims, because he wants to keep the jug afloat: “The trick is not to hit it but to make it float.”

You remember Goofy in the cartoons of the ’50s and ’60s. Mickey Mouse’s pal. You can call him up on YouTube if you don’t. Art Babbitt wrote in “Analysis of the Goof”:

Think of the Goof as a composite of an everlasting optimist, a gullible Good Samaritan, a half-wit, shiftless, good-natured […] hick. Yet the Goof is not the type of half-wit that is to be pitied. He doesn’t dribble, drool or shriek. He has music in his heart even though it may be the same tune forever and I see him humming to himself while working or thinking. He talks to himself because it is easier for him to know what he is thinking if he hears it first.

The Cowboy is the goof. Dippy Dawg was Goofy’s original name. Charles Solomon, in The History of Animation: Enchanted Drawings, described Goofy as a “hayseed,” or “blithe stupidity.” The Kid, trying to provoke the Cowboy, trying to egg him on and into his own death, trying to trick him into drawing down on the Kid, trying to make him goof up, calls the Cowboy names:

“Hey, hold it, Sonny. […] Hold up on your target practice a minute. I don’t want to get shot.”

“Well, then get off the bridge, you saddle tramp.”

“I want to buy some socks. I got a long ride ahead of me.”

“What’s wrong with the socks you got on?”

“I wore ’em out running around half-naked in that whorehouse over there. That’s really quite a place. You been there yet?”

“Take off your boots and show me.”

“Ha. You’re joshing me.”

“I said take off your boots and show me, ya egg sucker.”

[Cowboy turns to leave.] “I ain’t gonna do that.”

“What are you wearing that gun for?”

“Nothing. I just wear it. Can’t hit nothing with it.”

“Well, that don’t make no sense. What kind of a gun is it?”

“Colt.”

“Them’s good guns. That’s what I’ve got. Must be something wrong with it.”

“Nah, it’s me. I just can’t shoot good.”

“Well, let me see it. Come on, maybe I can fix it for ya.”

“Okay.”

[The Kid kills him.]

Self describes the scene as “[t]he sudden and inexplicable killing [that] violates the mythic code of the gunfight.” And he says, “Altman underlines its shock [the death of the Cowboy] with an echo on the two gun shots and a slow-motion zoom in to Cowboy’s body floating on its back in the pond, and then he repeats the climax of the shot for emphasis.”

Altman says: “The generic story of gambler, whore, and killers […] became an easy clothesline for me to hang my own essays on. […] I was able to say, ‘You think you know this story, but you don’t know this story, because the most interesting part of it is all these little sidebars.”

To be honest, I am at a loss to explain what it is about the Cowboy’s death that I want. I don’t want to be shot. Certainly not twice. Except to do so would be to die suddenly. Yet I can’t begin to imagine the pain. As I said, I don’t want to land in a mostly frozen pond. Icing my aging and bad knees after a run is barely bearable at this point.

I have been a goof. The butt of jokes. A fool. I don’t want to die a goof.

We are all obviously part of a bigger story: STORY. The Gambler’s Story. Lift up the Gambler’s Story and at a certain level of abstraction it is everyone’s story. But no one cares about the bigger story. Unrequited love. Requited love. So many. All the myths. Think about the Big Bang. Fascinating stuff. But today what you need is a drink, not an explanation of the undulations of the universe.

Andromeda is going to collide with the Milky Way in 300 million years. Worrisome. How scary. Really? Who cares.

I want to die in the quotidian.

Today I have a dentist appointment. My learning to play the saxophone may have caused tooth absorption. I need two implants. I may be able to play again; I may not be able to play again. That would be a personal loss of hope.

Big deal.

Golf

We left me at the edge of the rough, and I am less than 80 yards from the pin. The rough is not serious (high) rough. Let me retell the retelling of my golf story (and betray myself) — the plot may differ this time: I stand over my second shot; (back at the ranch) we left me about 250 or 260 from the green. My ball came to rest on the left side of the fairway. The Ledges’ fairways are in terrific shape. I can’t reach the green; I plan to layup, not that I have a choice. I pull my three wood from my bag, ease the cover off (which, as I said, is Teddy, our cocker spaniel), take a couple of practice swings, and a breath. My aim is to hit the ball toward the right side of the fairway and watch it take the slope and swing down into the middle. I make good contact. The ball sails over the post that marks 150 yards to the center of green; it lifts somewhat. It hits the ground, but doesn’t catch the slope. I end up about a foot into the rough. Disappointed, but I am less than 80 yards from the pin.

The green, pond-sized and tilted, slopes sharply — 45 degrees? — to my left. You can’t see that slant from the fairway. You can feel the downhill in your feet when you stand on the green.

My anticipations: The rough is not long, but it is the kind of rough that can turn a club in your hand. You can easily chunk the approach. You could shank the shot. My answer: Use a nine iron rather than a 48-degree wedge; I can control the speed of my downswing (less speed but sustain acceleration) and steady my hold on the club. Second: The lie of the ball — on the down slope — and the ball above my feet means I will pull the shot. Answer: Set up to the right of the pin. Three: I can’t see half of the green; there is a mound between me and it. Answer: Trust my distance and don’t try to aim the ball. Hit it; don’t think about hitting it. If I aim, if I think about the shot, I will slow my swing through the ball and not sustain the speed through the ball. Anticipation: One of my major weaknesses in life and golf is that I look to the end and, thus, look up before I have finished my swing. Answer: Don’t anticipate. I often chicken-wing this kind of shot. Or I stub the club into the turf.

I don’t.

I shift my weight through the rough, through the ball, and it flies high and about 20 feet right of the flag. I don’t see it land. The hill blocks my view. The shot feels right — height (to keep it on the green), place (about 10 feet onto the green), direction (above the hole). Then I see the ball appear on the green and turn in the proper place in the direction of the flag. It is on track, and it seems to be moving at an excellent speed.

I say, “Yeah, well, go ahead and go in.”

It does.

What If

Should I not get the wish I wish tonight — my second choice, which I have dreamed about five or six times now: I am learning to play the saxophone. (Which is a fact in life and in my dream.) My wish: I want to play it well enough that I can play the opening to Leonard Cohen’s singing of “Ain’t No Cure for Love”; I want to play at a live concert (London). I want to blow the opening and a few minds, wave the sax in thanks for the opportunity, go backstage, go home.

I want to play those notes for a woman I love. I want to play the notes better and better and better and still better (never to reach, please, the best) forever and for all time.

And never die.

¤

LARB Contributor

Darrell Spencer has published five books of fiction, including Bring Your Legs with You, winner of the Drue Heinz Prize for Literature; and Caution: Men in Trees, winner of the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction. He is working on a book about returning to golf after 50 years. He and his wife, Kate, an artist and writer, live in St. George, Utah.

LARB Staff Recommendations

We Lost It at the Movies

Martha Southgate ponders the formative experiences and changing landscape of going to "The Movies."

Hollywood Is Thy Name

Two new books explore the movies Hollywood made about Hollywood movies.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!