For Everyone Who Never Got to Be Innocent: On Jenny Zhang’s “My Baby First Birthday”

Diana Arterian celebrates “My Baby First Birthday” by Jenny Zhang.

By Diana ArterianMay 12, 2020

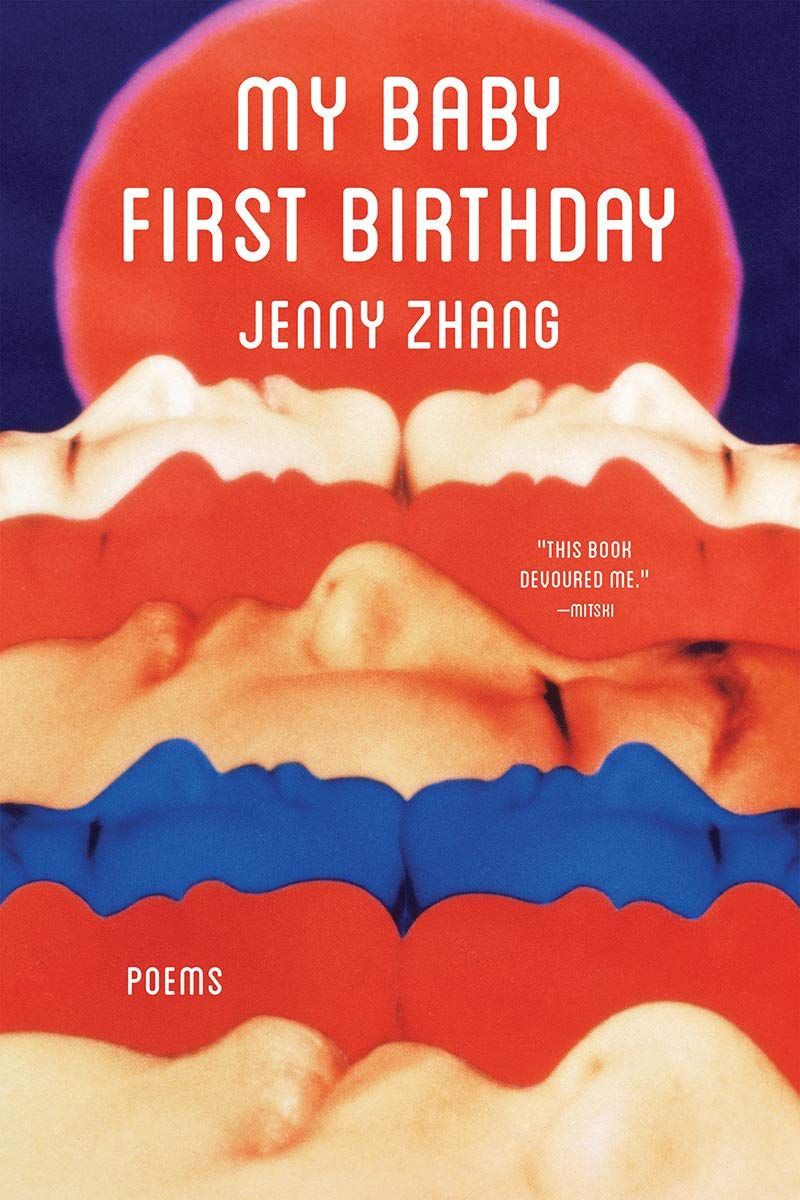

My Baby First Birthday by Jenny Zhang. Tin House Books. 186 pages.

IN HER ESSAY “Poetry Is Not a Luxury,” Audre Lorde calls upon her reader to privilege feeling over intellect, as the latter is associated with power, control, enslavement, whiteness, and masculinity. She writes,

Our poems formulate the implications of ourselves, what we feel within and dare make real (or bring action into accordance with), our fears, our hopes, our most cherished terrors. For within living structures defined by profit, by linear power, by institutional dehumanization, our feelings were not meant to survive.

In short: To honor feeling is a radical act, and to make art grounded in feeling flouts the very systems that subjugate all manner of people.

The poet, essayist, and fiction writer Jenny Zhang approaches her work with this ethos in mind. At first glance, Zhang’s latest poetry collection, My Baby First Birthday (Tin House), operates in a similar mode as her first, Dear Jenny, We Are All Find (Octopus). Both involve associative imagery, language play, and circle around family. Both evoke the gestures and textures of Hannah Weiner, Leslie Scalapino, Walt Whitman, and others. Yet My Baby First Birthday is more focused in its intent: to meditate on what it is to try to exist in a world that tells you time and again you are less than because of your identity — or that your value is only located in your suffering. “anything is easy if yr existence is wanted,” Zhang writes. And, elsewhere: “the problem is the most exotic thing / I could do is suffer / & I already do.”

While there are plenty of instances of suffering and trauma in these poems, it is largely an exploration of what it is to be born in a world that is hostile, and how to keep moving through it once you realize that is the case. One response is a call to action: “be the baby ppl didn’t let u be / for once in yr life / & see what happens.” Here, Zhang is asking us to privilege feeling, the unabashed kind you expressed when you were first ushered into the world.

My Baby First Birthday asks what it is to be born and what we are born with or into (identity, class, race, privilege, an injured planet). Even as a baby, a female already has all the eggs she will bear for her entire life, her baby form bearing up adulthood the moment she exists on the earth. Zhang writes on this phenomenon: “my mom was a baby too / and inside her was a teenier baby / if not for that baby / I would still be / essentially an idea.” Born into a body, we are meant to reckon with what society tells us it means. As the poet Morgan Parker writes, “My body is an argument I didn’t start.” The concern for Zhang is how not to allow that argument to reduce one’s body to its mere parts and functions. How do we carry our body, capable of producing pleasure and pain, in all our interactions with others as we move through the world?

The confusion sexuality, eroticism, and desire inserts into the already complicated reality of living isn’t lost on Zhang — indeed, it is a consistent concern she approaches time and again. Describing one sexual encounter, Zhang asks, “how did both of us come away from that / thinking the other was the nazi.” In another poem, Zhang expands on a bit by the comedian Wanda Sykes in which Sykes considers separating her vagina from her body: a “detachable pussy.” Leave it at home to go running without fear of rape — or before a date you think might go nowhere. Zhang pursues this image further, writing about a broadened sexuality. She writes, “my cunt gets leashed to a tree / and waves hello to everyone / like hi like hi like hi hi hi” and “in case this cunt dies / I have another.” In this same poem, Zhang provides a description of intersectional identity through absurd bodily detachment (the feminine, in this moment, able to continue loping forward, while the speaker’s ethnic identity exhausts her):

I am running to catch the bus

my cunt makes it

of course

but me

I am tired

I am out of breath

lying on a map

and the city where I was born

disappears mysteriously

The flip side of this sense of detachment, however, is the potential for deep connection and intimacy. This is something Zhang explores early on, writing of “the old country,” “the place where I was first touched / a sudden bloom of algae / in the ancient lake / where all the animals touched skin to skin fur to fur paw to paw fin to fin mouth to mouth hole to hole and became family.” Here, what is ancient is also fecund, bringing connection between species of all sorts through touch. The poems often move between sexual intimacy and intimacy with the speaker’s mother with such fluidity it startles. They seem to ask: What, exactly, isn’t erotic about the love between a mother and child? And, pushing this further, if the racialized maternal body is forced to endure all manners of eroticization — why not on her terms?

Zhang is able to consider such complicated topics through both expansiveness and brevity. The form these poems take is largely longer pieces, with very brief aphoristic poems throughout. Other short poems are pointed, such as one entitled “what is with you,” which reads: “and your need to not ever be blamed?” This might be from a family member or friend directed at the speaker in the other poems, or from the speaker toward those whose existence enables her subjugation. Zhang leans into the truth of both possibilities. “Everyone is flawed,” she states in an interview, “but some of us are punished lethally for it, and others get away with it ad infinitum.”

Zhang addresses the latter throughout My Baby in a consistent intimacy with nameless white “you”s in the collection. Perhaps they are lovers, friends, or the white imagination, the latter of which Zhang has been forced to encounter and contend with constantly since migrating to the United States, and probably before. “[Y]ou think I don’t see myself the way you see me?” she asks. Here and elsewhere, there are countless moments where Zhang is writing directly to white readers like me — and calling us out: “is your charisma a marriage / between being born lucky and finding a way / to still be damaged?” she asks. “the worst day of your life / looks exactly like one of my best.”

The worship of damage, particularly in writing circles, is a topic Zhang has addressed in several venues, discussing how this is often underscored by the racism of her “luck” at operating from a subjectivity that is “hot” in the market. “[I]s there really a class of people / who have never been hurt?” Zhang asks. “[I]s that why these fights last so long?” She also interrogates the eroticism ascribed to subjugation, white supremacy, and rage: “is it only catastrophe that gets you going?” and “you dry up and go limp / when someone calls for accountability.”

So much of Zhang’s work is intended to challenge her readers. She explains in an interview, “When something disturbs me, I turn inward[.] […] Some people go straight to blame, like: why did you do this to me? Why did you force me to feel this way?” This book has a rage I am more than willing to endure, but it is also framed in such a way so as to force me to ask why I think that may be the case. (Because I feel shame around my privilege? Because I think I’m one of the “good ones”?) Any work that provokes readers with my subject-position to deeply consider the roles they play in the author’s subjugation is undeniably powerful.

“Can whites begin to understand and take in the pain of this racist society?” poet and writer Toi Derricotte asks. “So often white people, when a deep pain with regard to racism is uncovered, want it to be immediately addressed, healed, released.” The absurdity of this impulse is something Zhang addresses time and again in this work: “why do the rich treat blame / like it’s an obscenity,” she asks, “or a fossil.” While the conversation is not — and cannot be — dead, there are no simple answers. The pain of a lifetime and all those before it is not a puzzle waiting to be solved, plain and simple.

For readers who relate directly to Zhang’s life experiences, I can only imagine she gives voice to so many of the feelings that have haunted them their whole lives. Posting a picture of the book’s cover on Instagram, Zhang writes in the caption,

I wrote this book for everyone who never got to be a baby, for everyone who never got to be innocent & never got to be born into a world that was soft & strong & willing to heal all the blood spilled by agents of greed, power, dominance. These poems are for anyone who has ever wished they had never been born, but try anyway.

Despite the depressingly bleak deficit in how we humans connect, the manifold ways we harm each other, knowingly and unknowingly, from birth, it continues. “[I]n the end it is almost impossible,” Zhang writes, “to say no to more life.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Diana Arterian is the author of the forthcoming poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern University Press/Curbstone, 2025). Her first book, Playing Monster :: Seiche (2017), received a starred review in Publishers Weekly. A poetry editor at Noemi Press, Diana has been recognized for her creative work with fellowships from the Banff Centre, Caldera, Millay Arts, Vermont Studio Center, and Yaddo. Her poetry, nonfiction, criticism, co-translations, and conversations have been featured in BOMB, Brooklyn Rail, Georgia Review, NPR, and The New York Times Book Review, among others. She curates and writes the column The Annotated Nightstand at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.

LARB Staff Recommendations

“I Wasn’t Even That Good”: On Megan Fernandes’s “Good Boys”

Rachel Carroll considers “Good Boys” by Megan Fernandes.

The Emancipation of Little Women: On Library of America’s “March Sisters”

On the limits of archetype and power of self-mythology in “March Sisters.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!