Fighting as Conversation: On Jaed Coffin’s “Roughhouse Friday”

"Roughhouse Friday" details Jaed Coffin’s hunger for a language he can call his own.

By Matthew JanneyJuly 14, 2019

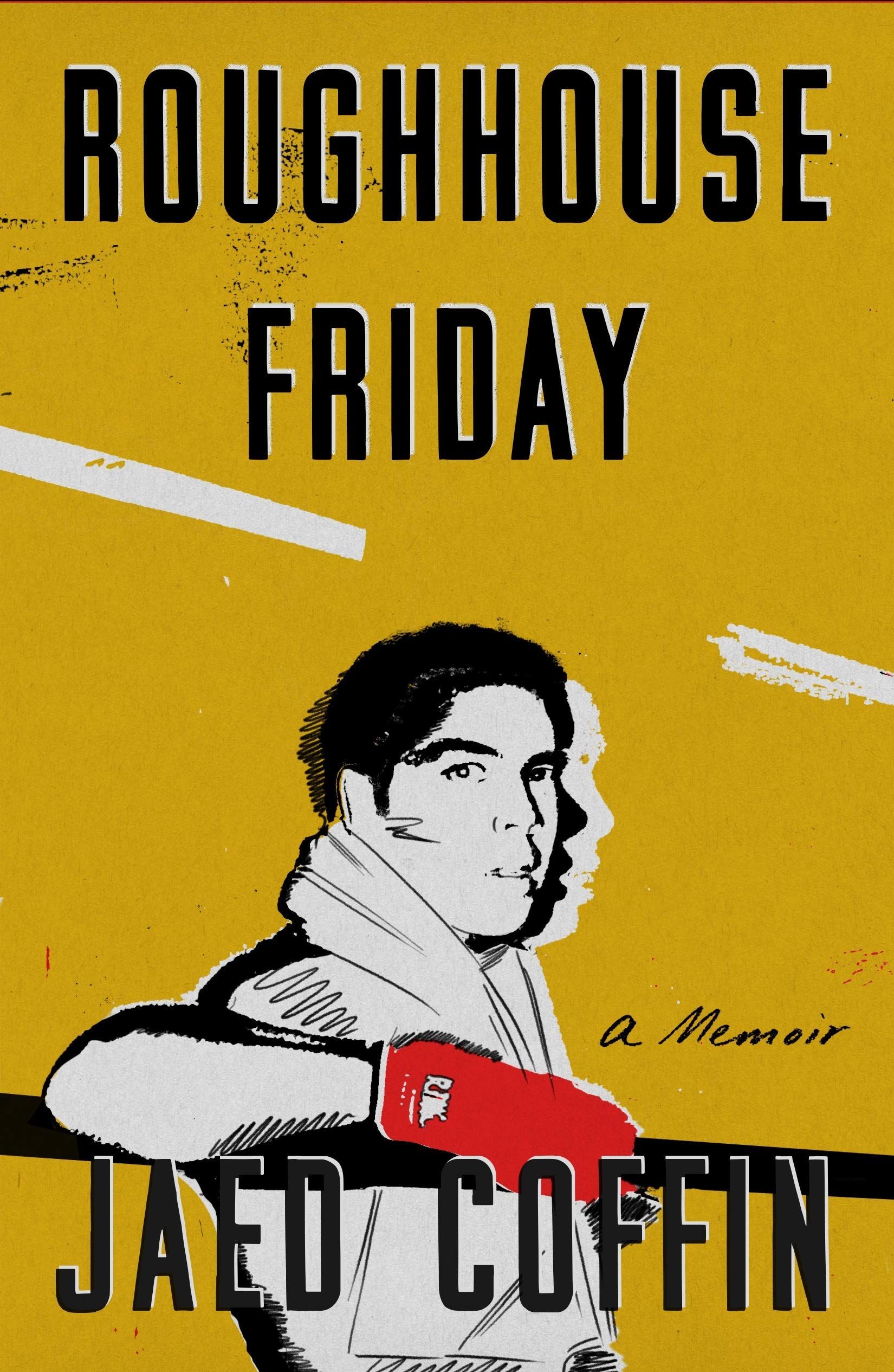

Roughhouse Friday by Jaed Coffin. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 288 pages.

NORMAN MAILER, A. J. Liebling, Ernest Hemingway, Joyce Carol Oates, George Bernard Shaw, and Arthur Conan Doyle are just some of the participants in literature’s great fascination with boxing. Much more than the primitive spectacle of fists on bare skin, boxing — like many novels — is so often infused with stories of human triumph, failure, and survival, the confrontation of pasts and forging of futures. As David Remnick writes in his historic New Yorker piece on Mike Tyson’s controversial fight against Evander Holyfield:

Boxers go into the ring alone, nearly naked, and they succeed or fail on the basis of the most elementary criteria: their ability to give and receive pain, their will to endure their own fear. Since character […] is so obviously at the center of boxing, there is an undeniable urge to know the fighters, to derive some meaning from the conflict of those characters.

No other sport commands such authorial attention. No question haunts writers more than what drives these athletes to such lengths.

Jaed Coffin’s lucidly written memoir continues this trend but complicates the picture. Roughhouse Friday recounts his time spent in Sitka, Alaska, after finishing college, where he falls into a local boxing community run by Victor, once the number-one-ranked fighter in Southeast Alaska. He ornaments his narrative in Sitka with memories from his childhood and tales of the region’s history, as if highlighting the tributaries that run into his central river. The book’s title refers to a monthly fight night that takes place in Juneau, Alaska, and bears all the hallmarks of amateur boxing showdowns: a seedy bar, girls in slinky bikinis, men wearing NASCAR jackets drinking pints of beer, and young boys from across the region slugging it out to be crowned the Roughhouse champion. At first glance, this lewd combination of testosterone and sleaze sounds like any other banal boxing story, but this is merely a glittery distraction to the memoir’s deeper preoccupation — Coffin’s compelling confrontation with his father, his mixed identity, and his ingrained sense of masculinity. At its heart, Roughhouse Friday details Coffin’s hunger for a language he can call his own.

Coffin grew up in New England, the son of an American father and Thai mother who had met during the Vietnam War. His father was a Hemingway-reading, Platoon-watching, Led Zeppelin–listening war veteran, while his mother worked night shifts as a psychiatric nurse. A feeling of living in between two cultures, two stories, two traditions, only intensified when his father left his mother and began a new family. It soon becomes clear, however, that what dominated Coffin’s childhood was his father’s particular branch of warrior masculinity: “When I was a boy, my father, during our weekly phone conversations, used to tell me stories about the mythical kingdom of Camelot,” the memoir opens. And Coffin, like any young boy, wanted nothing more than the approval of his father: “I spent my mornings guiding a small LEGO knight on a plastic horse across the mountainous topography of my bedspread.” It is this yearning for acceptance that leads Coffin to the boxing gym, compounded by an aimlessness that so often defines one’s early 20s: “I was one year out of college, wandering through that shapeless in-between period of my early twenties when I wanted badly to be in the process of becoming a man but didn’t know how to start.” Sharp insights are twinned with admissions of ignorance such as these. As a narrator, Coffin generates an intimacy with the reader by exposing the limitations of his analysis.

Alaska offers Coffin everything his childhood didn’t: escape from his parent’s unresolved pain; a sense of ethnic affinity (people regularly mistake him for Native in Alaska) in contrast to a predominantly white New England; and a simplified external identity that contrasts the complexity of his mosaic-like interior. Whereas at college, he buried himself in “French philosophy and literary theory” and “ancient Buddhist scripture” in his search for meaning, it is the ritualized cycle of “push-ups, sit-ups, burpees, heavy bag, followed by line work, mitt work, and sparring” that helps him make sense of his world. “[D]eclaring myself a Roughhouse fighter,” Coffin writes, “made me feel, perhaps for the first time since I’d left home, a new certainty about who I was, and how I should spend my time.” While these exercises are ostensibly ways to prepare for a fight, they are in fact part of an embodied conversation, physical substitutions for the words he cannot say. Before his first Roughhouse Friday, Coffin reveals: “[A]s I stood watching the men in the ring […] I had no awareness of why I was fighting beyond that my body was telling me to.”

The book’s chapters play out in line with the monthly bouts at Roughhouse. With each fight, Coffin draws closer to articulating the kernel of his pain. As a teenager, Coffin reveals he came close to fighting an opposing player on a soccer field after being called a “fucking refugee,” but stopped short “fists clenched, mind screaming, paralyzed by a feeling with no name.” But as Coffin hones his footwork, jabs, and uppercuts in the ring — under the guidance of his paternal trainer Victor — his indescribable inner feelings begin to crystallize into language.

To feel anger at a parent is to shatter the illusion of their perfection. Recognizing this gap between who a parent actually is and who we might want them to be is essential work in transitioning from childhood to adulthood. The book’s most powerful moments occur at the arrival of these realizations: Coffin reveals how he began to see how his father created the terms of his mother’s existence; he describes the heroes of his father’s favorite films to be “disillusioned white men unable to make sense of the world”; he realizes his father’s career moves were made at the cost of his family. While Coffin unravels these knots with an impressive emotional dexterity, some are perhaps too tightly woven to see. At one point, Coffin reflects on his father’s advice that he should treat women remembering they were once “somebody’s little girl.” Coffin correctly highlights the sexist connotations of his father’ advice, pointing out that treating a woman with respect was about honoring their father. But what Coffin fails to notice is his own sexism; “somebody’s little girl” could also be relating to the mother. Though he has gone some way to shed the skin his father has wrapped around him, its flakey residue remains.

While he strives for connection, Coffin’s relationships with women remain distinctly unsophisticated. Aside from two casual affairs in Juneau that end in mutual abandonment, his closest romantic relationship is with a young woman named Miss Mary in Sitka. Upon leaving, Coffin wants to thank her for the time they spent together, but simply cannot summon the words: “[D]espite being the toughest guy in Southeast Alaska, I lacked the courage to tell her those things, so I did what I always did: replaced honesty with distant and remote silence passing as masculine cool.” What Coffin intends as self-deprecation comes across as macho ignorance, mistaking physical courage with emotional literacy. Conversely, it is witnessing a boxing match in Juneau between two women that triggers Coffin’s damascene transformation: “Watching her,” Coffin writes, “I understood something about myself: that all the feelings that had led me into the ring were useless to the world if I could not understand that beneath them — as their cause, their reason and longing — ran a vicious current of love.” It’s a compelling statement, but unconvincing in light of Coffin’s romantic indifference.

Roughhouse Friday is therefore the search for a new language that never quite manifests. But it was by no means in vain. Coffin’s triumph lies in ridding the language of his father, a language that compelled him to dwell in a house he did not recognize as his own. We wonder why these athletes want to fight, want to push themselves to such physical extremes. Coffin offers perhaps the sharpest explanation one could hope for:

The quiet vein of violence that ran through me, that made me want to fight, was not my own, did not belong only to me. It was the tail of a much longer story, of friendship and betrayal, race and love, dislocation and war. Of whale hunters and rice farmers, pilgrims and soldiers, sons and lovers. And now it had found its way into my life for a brief moment. And this whole time I had been thinking that I was the weapon, that I was the sword, when, really, I was only its temporary home.

¤

Matthew Janney is a literary journalist and short story writer based in London.

LARB Contributor

Matthew Janney is based in London and writes about books for Culture Trip. Previously at The Calvert Journal, Matthew also co-founded a literary collective called The Danube Club with members across the UK. You can find him tweeting, sparingly, @mattjanney25.

LARB Staff Recommendations

World War II’s Poisonous Masculine Legacy

Josh Cook reviews Jared Yates Sexton's new book, "The Man They Wanted Me to Be: Toxic Masculinity and a Crisis of Our Own Making."

Warning to Heed: On Adam Nemett’s “We Can Save Us All”

Dan Hajducky reviews Adam Nemett's promising debut novel, "We Can Save Us All."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!