Featuring Emily Dickinson and Phoebe Bridgers: A Conversation with Andrew Bird

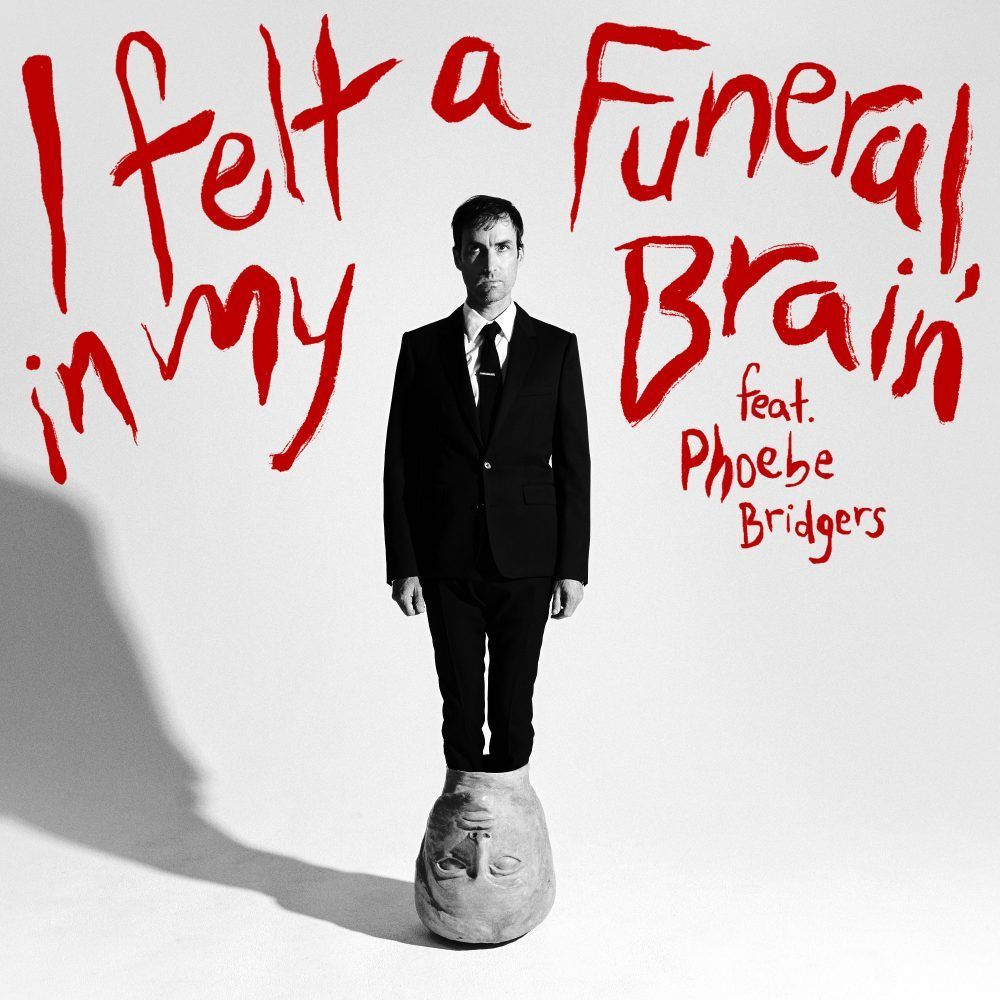

Elizabeth Metzger interviews Andrew Bird about his new single, “I felt a Funeral, in my Brain,” featuring Phoebe Bridgers.

By Elizabeth MetzgerNovember 16, 2022

INDIE SINGER-SONGWRITER Andrew Bird recently released a perfectly Halloween-timed rendition of Emily Dickinson’s “I felt a Funeral, in my Brain,” featuring the haunting and ethereal voice of Phoebe Bridgers, folk-rock musician extraordinaire. Rich with instrumentation from celestial strings to otherworldly whistling, this harmony immediately brought to life a quality of mystery and physical intuition I feel when reading Dickinson’s poems. And yet, I was struck by the interplay of two voices, which never felt like two separate people but two layers of consciousness. Because Dickinson was especially private (and, of course, we have no recording of her voice), hearing her poems aloud has always felt shocking to me. To hear this poem sung by two voices only multiplied my questions about Dickinson’s poetry and the nature of her “supposed person,” which is how she thought of her lyric “I.”

Reverent and irreverent, dead and alive, absolutely solitary and unabashedly multiple, the speakers of Dickinson’s poems occupy a powerful, if disembodied, presence that has always seemed to allow the poems to become immediately the inner, intimate, and contradictory world of our — her readers’ — consciousness. Though enigmatically reclusive, death (the central metaphor of this poem) was a very real part of the poet’s life. Dickinson’s “flood years” of creativity overlap with the Civil War. I think it was the poet Mark Strand who once said that from her bedroom window, which faced a cemetery, funeral processions were Dickinson’s reality TV. Of course, in this poem, she is not just a witness but an embodiment of the funeral.

At once soulful and cosmic, Andrew Bird’s “I felt a Funeral, in my Brain” illuminates the expansion or birth of a creative part of the brain that simultaneously feels like the plummet or death of another. “I felt a Funeral, in my Brain” served as inspiration for Bird’s new album Inside Problems, so we talked about his relationship with Dickinson, his interpretation of the poem, and the way it spoke to his own inner world and creative process. This conversation took place over an email exchange the week the song was released.

¤

ELIZABETH METZGER: Is “I felt a Funeral, in my Brain” a poem you’ve had a relationship with for a long time, or was it a recent discovery? Was there a significant moment in your life when this poem came, or returned to haunt you?

ANDREW BIRD: I first read this poem two to three years ago as I was writing Inside Problems. I was on a bike ride with a friend who teaches a class on Emily Dickinson, and he mentioned this theory that all her poems can be sung to the tune of “The Yellow Rose of Texas.” I didn’t want this to be true, and there was an air of dismissiveness about it. I started reading her poems again to disprove this theory but got so drawn in I sort of forgot about “The Yellow Rose” and was reading with an ear toward what would make a great song.

You mentioned learning about Dickinson’s editing history, how she was sort of straitjacketed into typical poetic conventions by male editors, including her esoteric punctuation, capitalization, and lack of titles. Did you feel this contributed to your experience or the way you saw your role in adapting the poem to music — more hesitation, more freedom, something else?

Well, speaking to this “Yellow Rose” theory now, it seems likely that those first editors ironed out all her halting punctuation and anomalies such that you could sing them all to “The Yellow Rose of Texas.” I recently tried “Funeral” to this tune, and it certainly bucks at being straitjacketed as you say. Rather than having lines like “finished, knowing, then —” as a lyrical problem, it’s those moments that make the poem and make it worth singing.

Dickinson famously defines poetry in a letter to one of her frequent male editor-correspondents: “If I read a book [and] it makes my whole body so cold no fire can ever warm me, I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only ways I know it. Is there any other way?” Is there a particular moment in this poem that gives you that top-of-the-head feeling, or that felt like a portal for you — where accessing it, interpreting the poem, and making it yours became possible? On the other hand, were there parts of the poem that felt more elusive, hard to make sense of, as you started to dwell in them?

For me, it’s the stanza that occurs twice as the bridge in this song setting: “And creak across my Soul / With the same Boots of Lead, again.” The first three stanzas have this persistent “treading — treading […] beating — beating,” then boom — it rips the top of your head open with that line. That’s why I wanted the first line of the bridge to be so dissonant, so when the major second cleaves apart to a third, it feels like something is being torn apart. The next two stanzas were the most challenging to figure out the phrasing, especially “Being, but an Ear,” but Phoebe’s crystalline voice was able to separate the words so it didn’t sound like “boutonnière.”

I hadn’t thought of that! At first listen, a duet might seem a surprising a choice for such a solitary poem — I think of the lines “And I, and Silence, some strange Race / Wrecked, solitary, here.” As soon as I listened, I felt this was the most genius aspect of the song for me, the internal tension you and Phoebe create. I heard her voice functioning as another layer of consciousness, how her voice gradually enters, joins your voice, eclipses your voice in a solo after the cosmic interlude, and then joins with your voice again, before fading away, leaving only your voice at the end. I’d love to hear you talk a little bit about the choice to have two voices on this track and what this means for the inner world of this poem, or for you in particular? How does the harmony speak to or change the poem for you?

Many of my songs that become duets begin as an internal argument, but since it’s all internal, there’s no need for pronouns or casting different voices for which self is speaking. “Funeral” is pretty clearly a monologue, so I wasn’t sure how slicing it up between two voices was going to work. All I know is I recorded it solo more than a year ago for the album and didn’t think it was strong enough. [Including] six verses from the same voice was more than a song could sustain. I remember Phoebe commenting that she thought it was cool for a single monologue to be split. I honestly don’t know why it worked. At first, Phoebe was going to just sing harmony, but I was hoping she would sing lead.

Dickinson had so many versions and variations of her poems (even word alternatives marked with a little x). Because she didn’t publish many poems, the versions get to coexist in a fascinating way rather than the way we usually think of rough and final drafts. Some of this unfinished feeling may be why Dickinson’s poems feel so open to interpretation, or, maybe more accurately, more open to being inhabited. Did you find yourself interpreting the poem in various ways and versions, or did it sort of come to you this way from the start? Were there facts about Dickinson’s life you knew or researched that influenced your rendition?

That first version that I did for Inside Problems was much more melodic, and that’s perhaps another reason it didn’t work. Melody is like a sugary cocktail where you can’t taste the alcohol. To make the words hit harder and to capture the droney dread of those “Boots of Lead,” I settled on a two-note alternating melody. It’s only a step away from speaking at times.

Speaking to what we know about Dickinson as a person, she makes me think of certain times in my own life when what it takes to get along in the world and have a healthy social life are at odds with this internal world and the lifelong struggle to translate and project it out to the world.

One of my favorite (if subtle) parts of this poem is the last word, “then,” which to me is not a definitive finishing but an arrow onward. The word then points both to the past and to the future, which makes the poem and thus consciousness feel powerfully circular. I was very moved by the way you let the final stanza direct you back to repeat the first stanza so that you actually end with “That Sense was breaking through.” Your song leaves us with the opposite of finality, it seems. Where do you think this poem leaves us, emotionally or otherwise? What is that breakthrough of sense?

I’ve always struggled with the expectations that songs be cyclical rather than linear, but it makes sense to have a refrain of “creak across my Soul” and to return to “I felt a Funeral” to make it work as a song.

As far as where this poem leaves us, I think she or “a supposed person” has collapsed and hit the bottom. It’s the falling that’s the worst, but when you are finally empty, a kind of giddiness can take hold. Perhaps it’s hope? I picture her looking up at the broken scaffolding of her fall. I relate to this. Perhaps I’m projecting, but that’s a big part of it.

I mentioned the word solitary above, but what about that other word in the line which becomes the speaker’s companion — silence? The dash is such a unique and omnipresent feature in Dickinson’s poems. It shows the hand on the page, marks time, offers a sense of the rhythm of thinking itself. Dashes also allow for gaps in syntax, places for the reader to make connections and leaps. For me, they make silence a present part of speech, an invitation for the reader to become the lyric “I” and make their own sense of the poem. How do you think of these dashes in the poem, but also, how did they influence your song?

I like that “show the hand on the page.” When I’m writing my own songs, I’m trying to find words to fit a melody and running through countless variables until the words come and fit into place. When I’m setting a poem, I read it aloud and see what resonates and try to unlock the melody that’s buried in there, so it’s quite a different process. As for the dashes, sometimes I heed them, as with “Space —” and sometimes I have to let it remain a mysterious part of the poem, as with “then —”

I’ve listened to your song so many times — eyes closed, eyes open, in darkness and light, in silence and with the background noise of my children dropping dishes — in each case, I’ve heard new aspects that overpowered me. But one moment where my eyes consistently bug out is the line “My mind was going numb” and how you repeat it in the variation: “My mind was growing.” I had to relisten many times to see if I was missing something or mishearing and honestly could not remember if the poem used the word going or growing. To me, the choice to include this additional variation, the juxtaposition of “going numb” and “growing,” captures so much of what this poem expresses about consciousness. Can you talk about your choice to repeat/vary that line?

When I’m living with a song for a few years, it starts to drift from where it started. To be honest, I was aware that I might have sung the wrong word there, but I liked the performance, so I let it lay.

Are some of the very minimal changes more to do with what sounds better sung versus spoken? I notice, for example, that you don’t sing the words “kept” in lines three and seven, but the way you bring in instrumentation seems to capture the ongoingness of “kept” as does so much else about the song.

It’s that drifting that I assume happens for some subconscious, intuitive reason.

Though full of doubt and irreverence (at least as much as reverence), Dickinson did choose to use the hymn meter of the church (iambic tetrameter, subverted with slant rhymes and modifications where needed). I mention this because of course she was working with a sung rhythm to begin with. Do you think this contributed to how you heard the poem when you first read it? If you’ve worked with other texts, was there something easier (or more challenging) that resulted from the poem being written in hymn meter?

I set two poems by Galway Kinnell to music many years ago — one called “Wait,” which I had to alter significantly with the poet’s blessing. Like I said, Dickinson is stretching the boundaries of that hymn form, but it certainly helps to have that form.

I can’t wait to listen. “Wait” is one of my favorite poems, so full of urgency. “I felt a Funeral, in my Brain” uses a spiritual lexicon (“Heavens”) as well as a scientific one (“Brain”). In other poems, she brings together geometry and witchcraft or faith and the (recently invented) microscope. I noticed in your video that there are images of cells and microscopic activity as well as X-rays. Did the poem conjure up the spiritual for you, the scientific?

It all helps us visualize her inner space. It’s like she went to the bottom of the ocean and has returned to report what it’s like there. I like how she breaks out of the claustrophobic funeral and enters this space and a sense of wonder prevails. This poem made me think of the parts of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest where there’s a girl in a hospital bed explaining what severe depression feels like: like all her cells screaming at once, or something to that effect.

Thinking about that on the cellular level is fascinating. When I think about the synesthesia of sound and feeling in this poem, I wonder how you experience music (making and listening to it). I am thinking of the phrase “Being, but an Ear.” It’s that singular, capitalized Ear near Being. Does the voice always begin with the ear — how does singing relate to listening for you? Do you experience a song coming into being as physical sensation, or did you know you were a musician because you experience or make sense of the world mainly through sound? Does it feel as if songs are writing themselves in your head before you reach for an instrument?

I’ve always had a visceral reaction to tone and texture. An icy ’80s snare drum or ’70s pedal steel guitar can make me sick to my stomach. Does a melody or do the words have enough teeth to gain traction in your mind? It’s a fine line between comfort and discomfort that I’m playing with. A “nauseouselation.”

Great word! I think of the poet Lucie Brock-Broido (also very influenced by Dickinson) who made up names of places for feelings. For example, the “abandonarium.” For me, your cosmic instrumental interlude (between “Then Space — began to toll,” and “As all the Heavens were a Bell”) radically captures the dimensionality of space. The whistling especially feels like it does some alchemy to my soul — breath turning into sound, time making space or space marking time. I’d love to know how you conceived of that middle instrumental section of the song?

I didn’t want the words to go down too easy with a sweet melody, but the interlude is pure melody, and I put the whistle far in the distance by using only the reverb chamber and not the direct mic, thus creating depth. Those queasy lines are a fretless guitar played by Blake Mills making us feel like time is elastic.

Though a funeral suggests a loss, I think of this poem as an exploration, even celebration, of the imagination. You have mentioned how this poem speaks to being deeply in your head (and the artwork conveys this powerfully as you stand inside a ceramic head, casting a shadow). Do you think of this song as an exploration of your own creative process? Do you feel a difference in your brain (or consciousness, body, emotions) when you are writing a song versus when you are performing it — is there something final about the recorded version, or does the song feel like a different experience each time you play it?

The best songs are blueprints, and every time you sing them, there’s plenty of room to accommodate the way you feel at that moment. This song always makes me feel connected and present. When I’m writing a song, there’s the excitement that no one knows yet what you’ve discovered, and that potential energy is potent. When you are deep in a depressed state, you are incapable of writing poems like this, which makes me think of Emily looking up at that broken scaffold and saying, Wow, how did I get here? It’s a dispatch from her inner world.

All I know is, left to their own devices, those spiraling thoughts can leave you feeling powerless. You try to take deep breaths and think of some fond memory, but it’s a flimsy Band-Aid. Organizing words and melodies in my head is a bulwark against that chaos and anxiety. I became acutely aware in the last three years of writing songs as a defense. It’s why we write.

¤

LARB Contributor

Elizabeth Metzger is the author of Lying In (2023), as well as The Spirit Papers (2017), winner of the Juniper Prize for Poetry, and the chapbook Bed (2021). Her poems have been published in The New Yorker, The Paris Review, Poetry, American Poetry Review, The Nation, and Poem-a-Day. Her essays have been published in Boston Review, Guernica, Conjunctions, PN Review, and Literary Hub, among others. She is a poetry editor at the Los Angeles Review of Books and lives in California.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Self Is a Collaborative Thing: A Conversation with David Baker

Daniel Shailer asks David Baker about his new collection of poems, “Whale Fall.”

Second Acts: A Second Look at Second Books of Poetry: Kate Daniels, Chloe Honum, and Corey Van Landingham

Lisa Russ Spaar takes a look at second books of poems by Kate Daniels, Chloe Honum, and Corey Van Landingham.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!