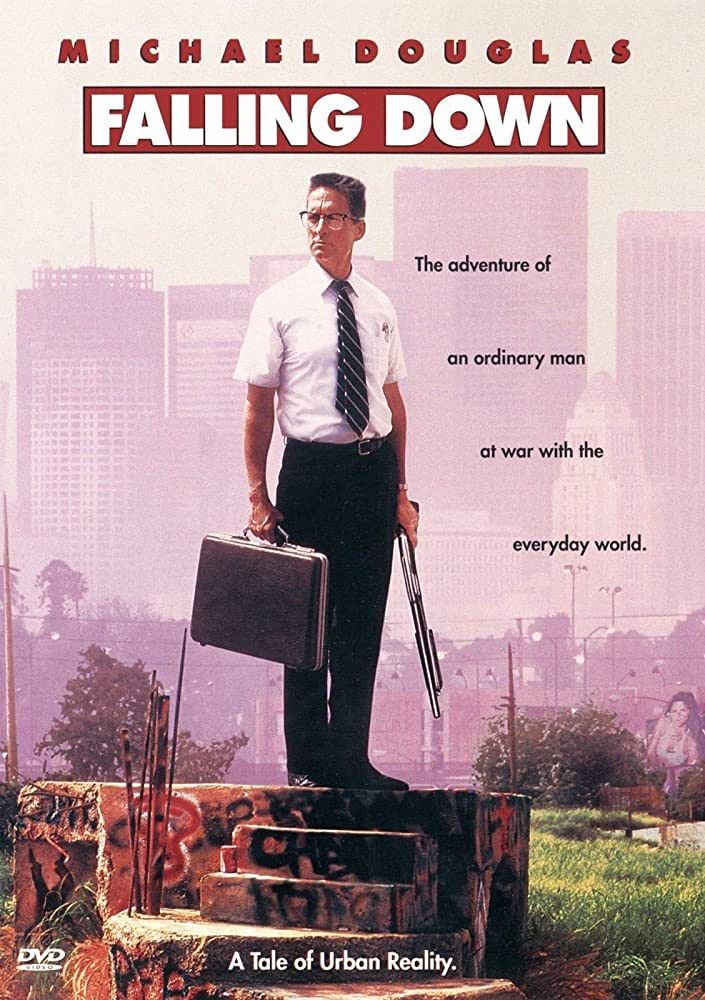

Fatal Flâneur: On Joel Schumacher’s “Falling Down” and the Sidewalks of Los Angeles

Carl Abbott revisits Joel Schumacher’s “Falling Down,” starring Michael Douglas, for the film’s 30th anniversary.

By Carl AbbottFebruary 26, 2023

FALLING DOWN opened in American theaters on February 26, 1993, introducing moviegoers to unemployed defense industry worker William Foster (Michael Douglas), whose frustration boils over when construction jams a freeway access ramp during a brutal Los Angeles heat wave. The air conditioning in his Chevy Chevette doesn’t work; the handle breaks when he tries to roll down the window; he can’t tell how long the stoppage will last. The inciting incident of Foster’s volatile spiral is his decision to abandon the car and start walking toward the Venice home of his ex-wife (Barbara Hershey), as he is determined to see his daughter on her birthday. Nobody joins him for an exuberant La La Land frolic — he walks off to the tune of heckling and honking, fated to traverse the city alone.

The film’s narrative spine is Foster’s trek from East Los Angeles to the Pacific. On the 20-mile slog, he has increasingly violent encounters with Angelenos who obstruct his path with ordinary nuisances, including a Korean convenience store owner who won’t give him a discount, Latinx street youth who hassle him for loitering on their turf, a fast-food restaurant manager who won’t serve him breakfast, and a neo-Nazi surplus shop owner whose bigotry disturbs him (and whom he ultimately kills). Intertwined with his journey is the effort of LAPD detective Martin Prendergast (Robert Duvall) to track a series of strange incident reports, identify Foster, and pursue his arrest. The film ends on Venice Pier with suicide by cop: Foster, cornered by the detective, pulls what proves to be his daughter’s water pistol, forcing Duvall to shoot him.

Falling Down, directed by Joel Schumacher, arrived at a traumatic moment for the United States, released on the same day that international terrorists detonated a car bomb at the World Trade Center, killing six people and injuring hundreds more. Two days later, federal agents raided the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas, setting off a siege that ended with the fiery deaths of 82 cult members. It was also a troubled time in Los Angeles. The 1992 L.A. riots, following the acquittal of the police officers who had brutally beaten Rodney King, led to 63 deaths and devastated entire neighborhoods, and incidentally interrupted Falling Down’s final days of filming. The revolt was a painful manifestation of the persistent racial tensions and class inequality that Mike Davis dissected in his passionate polemic City of Quartz (1990). The end of the Cold War also sent the aerospace industry into steep decline in the early 1990s, providing a backdrop for Foster’s story.

Much of the film’s early criticism centered on its racial stereotyping and near vindication of vigilante violence in response to the perceived injustice experienced by a self-centered white American. Los Angeles Times film critic Kenneth Turan called it a “greedy picture” that was “eager to get credit for the way it uses serious social problems as shallow window dressing in an urban fantasy” where the everyman transforms into the Terminator. This violent American everyman is trying to restore his personal sense of order. The reality that Foster, and men like him, might not be “economically viable” (a phrase repeated throughout the film) challenges his idea about what he is due as a middle-class white male. Struggling against his downward mobility, he assumes the privilege to enforce class conditions and social niceties that he thinks should be guaranteed. His grievances resonate with the fearful suburbanites in City of Quartz who are “against traffic congestion, mini-mall development, airport expansion, […] the erection of a mosque, an arts park, […] trailers for the homeless, the disappearance of horse stables, and the construction of a tortilla factory.” Foster protests obstacles that he feels he doesn’t deserve, like the loss of his job, and his ex-wife’s restraining order. In his self-righteousness, however, he becomes an agent of chaos whose violence escalates from swinging a baseball bat in one corner shop to murdering the proprietor of another. For balance, Duvall’s detective character represents the sort of calm and rational order that Foster thinks he is upholding.

Falling Down explores the ways that we imagine cities, Los Angeles in particular. Foster is a character who considers himself displaced, evicted from what he assumed was the promise of Southern California prosperity. And most obviously, he is out of place because he is out of his car. To complete his cinematic arc, he must experience, at three miles per hour, the reality of Los Angeles, a city he has previously known only as an abstraction.

At the start of the film, Foster finds himself barred from the elevated world of the freeway. California terminology contrasts freeways with “surface streets,” a term far more popular in Los Angeles than anywhere else. Freeways are nimble and direct, at least in theory, while surface streets are slow and earthbound. Reyner Banham, in Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies (1971), positions the freeway system as “autopia,” where near-mystical awareness was possible, in contrast to the vast swaths of residential neighborhoods that constitute the “Plains of Id,” where mundane life plays out.

Whereas an exploration of New York could easily start and end on its subways and sidewalks, the Los Angeles imaginary has popularly been inhabited by the automobile and its image of freedom and serenity. As writer Iain Borden points out in Drive: Journeys Through Film, Cities and Landscapes (2012), to transgress in the world of automobiles is to go too fast, to break both the rules of the road and the rules of conformity, as in Rebel Without a Cause (1955). Foster’s transgression is the opposite. By impulsively abandoning his car and tromping across the city on foot, Michael Douglas’s character subverts the common imaginary. Joan Didion in The White Album (1979) comments that freeway driving “is the only secular communion Los Angeles has,” requiring “total surrender, a concentration so intense as to seem a kind of narcosis, a rapture-of-the-freeway.” Foster can’t access this meditative transcendence when he is stuck in bumper-to-bumper traffic, bedeviled by a buzzing fly that is just as trapped and desperate as himself. He becomes a walker in the city, a status that unsettles his dearly held identity and exposes him to unfamiliar scenes.

Foster’s resulting encounters are not what urban theorists seemed to have in mind when studying sidewalks as sites where city dwellers perform their identities through strolling, shopping, and hanging out in “third places.” Most famously, an idealized Paris stoked the imagination of Walter Benjamin and his celebration of the flâneur. Michel de Certeau wrote in the same vein in The Practice of Everyday Life (1980), highlighting “the ordinary practitioners of the city” and the everyday experience of the sidewalk. His book offers a democratic utopian vision in which the city emerges from the networks and interactions of “walkers” going about their lives.

An earlier take on the challenge of walking in Los Angeles is Ray Bradbury’s “The Pedestrian,” published in 1951. Bradbury, who famously never learned to drive, was inspired to write the story after being questioned by police while walking in Pershing Square in 1940, and along Wilshire Boulevard in 1949. In “The Pedestrian,” the year is 2053, and Bradbury’s protagonist, Leonard Mead, is the only person left who still walks around the city, enjoying nighttime strolls along empty streets. But his muffled flânerie ends when robotic police cart him off to a mental institution to be treated for his deviance. Unlike Mead, Foster’s walking is not simply a source of solace that is misunderstood by the authorities, but a goad that pushes him toward mental breakdown and assisted suicide.

Fueled by anger and adrenaline, he passes through East Los Angeles, skirts Downtown, and aims west toward Venice Beach, traversing a “suburban,” low-rise landscape of neighborhood commercial strips and single-family homes, with the high-rise city skyline seen only in the distance. As he slogs westward, Foster crosses long-held racial, ethnic, and class boundaries of a changing metropolis that causes him more and more strain. Urban cultural historian Eric Avila frames Foster’s troubled day as an enactment of earlier nativist hostility toward Asian and Mexican immigrants that further anticipates anti-immigrant measures like Proposition 187 in 1994, which denied social services to undocumented residents, and Proposition 227 in 1996, which curtailed bilingual education. Foster’s nostalgia for an era before the onslaught of immigration to Los Angeles is apparent early in the film when he announces to the Korean convenience store owner that he’s “rolling prices back to 1965.”

In the universe of Falling Down, Detective Prendergast traces his finger along the first of two maps, suggesting that Foster is moving south from Lincoln Heights through Boyle Heights, where his confrontation with local teens occurs at the nonexistent “Angel’s Flight Hill” located southeast of Downtown. Foster then heads west to MacArthur Park, through Pico-Union, and then through the more upscale Rancho Park and its adjacent golf courses. Prendergast later maps a straight line from Rancho Park through Mar Vista and, finally, to Venice. (In reality, this journey is possible to recreate but requires some unrealistic loops within the basic east-to-west framework.)

Foster is less a flâneur than a terrible tourist who previously encountered Los Angeles as a sort of flyover country, or at least suspended animation. When Foster is moving on foot, Los Angeles is a foreign land that forces him to confront internal frontiers and boundaries, as the film’s screenwriter Ebbe Roe Smith has commented. Foster refers to the tussle with some Eastside cholos as “a territorial dispute,” and the police later wonder what a white guy in a tie had been doing in gangland. Later in the film, unhoused park dwellers make territorial claims, too, as do some elderly white golfers who tell Foster that he doesn’t belong.

Lacking a map of his own, Foster becomes an outsider-explorer of the shifting westward landscape, much like Lewis and Clark, only armed with automatic weapons instead of a flintlock. Foster’s journey, along with his life, ends at the coast, where the Pacific represents the triumphal trophy of the American continental frontier, and the end of Foster’s excruciating expedition. The twist is that Los Angeles was built not only by westward migration but also by northward and eastward migration. And the Pacific shore where Foster’s journey culminates has long been a pathway for many newcomers who have revitalized the city’s landscape — including, perhaps, the Korean storeowner who so annoyed him early on.

I want to end with a thought experiment. Like Ray Bradbury, Octavia Butler was a Los Angeles writer who never learned to drive. From 1970 to 1989, she lived on West Boulevard and regularly took the bus to write downtown at the Central Library, to go to the beach in Santa Monica, or to visit family in Pasadena. As writers do, she filled her notebooks with observations on what she saw out the window, and even set her story “Speech Sounds” (1983) on a Los Angeles city bus. I like to imagine that if Butler had encountered William Foster soon after he ditched his Chevy, she might have clued him in to the city’s public transit system and helped him find the right bus route to Venice. There would have been no movie, of course.

¤

LARB Contributor

Carl Abbott is professor emeritus of urban studies and planning at Portland State University and the author of Imagining Urban Futures: Cities in Science Fiction and What We Might Learn from Them. Other publications include Frontiers Past and Future: Science Fiction and the American West (2006); Imagined Frontiers (2015), which includes essays on Kim Stanley Robinson and on Firefly; and prize-winning books on the history of American cities and the American West.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Sometimes I Am What I Really Am: On Mark Alice Durant’s “Maya Deren”

Emma Kemp reviews Mark Alice Durant’s new biography of the enigmatic experimental filmmaker: “Maya Deren: Choreographed for Camera.”

Digging in the Dirt: On Jennifer West’s “Media Archaeology”

David Matorin reviews Jennifer West’s debut artist monograph, “Media Archaeology.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!