Fading Memories: On Sly Stone’s “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)”

Matthew Ritchie reviews Sly Stone’s “Thank Ya (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin).”

By Matthew K. RitchieMarch 11, 2024

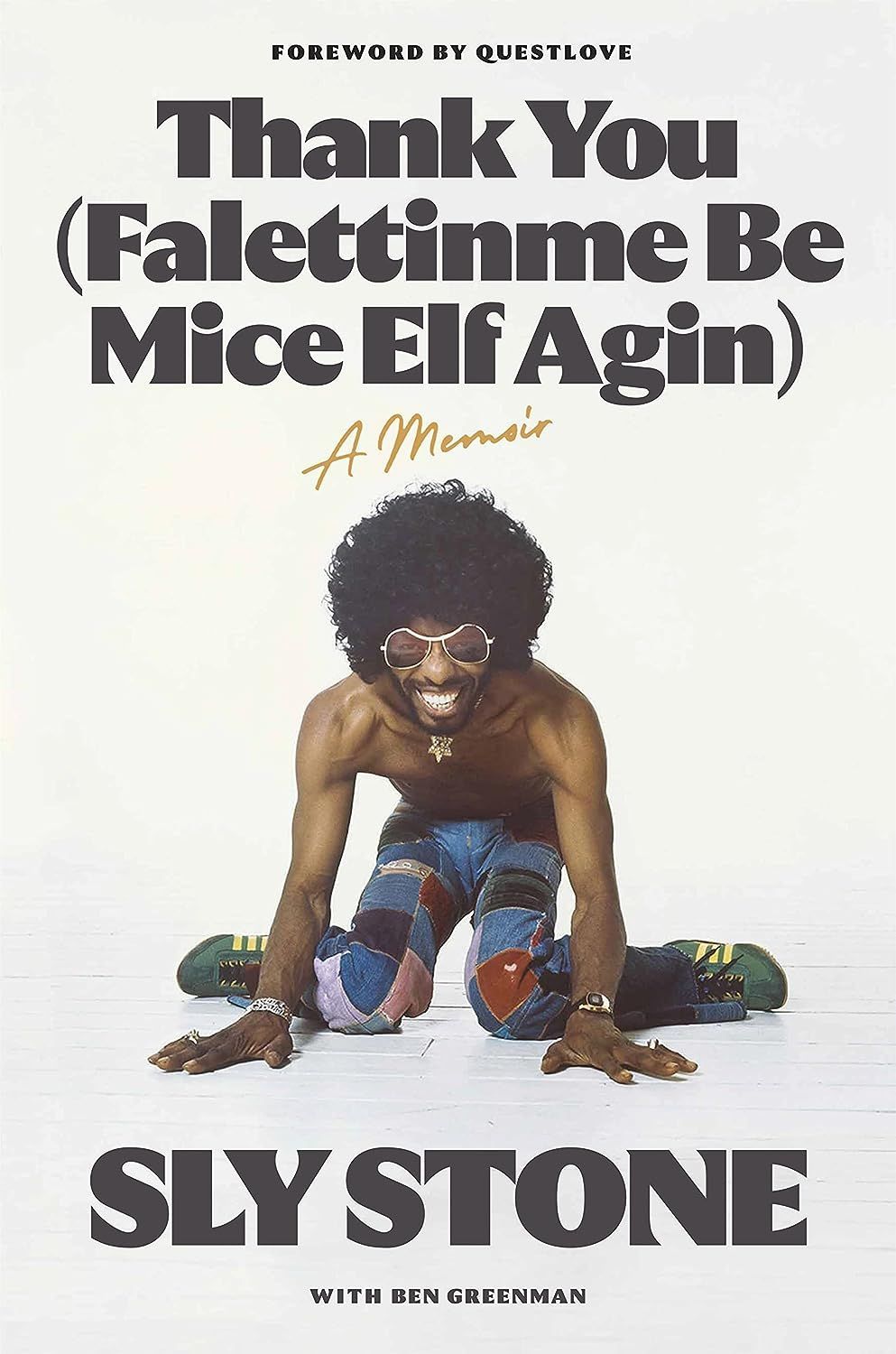

Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin) by Ben Greenman and Sly Stone. AUWA. 320 pages.

WHILE SLOWLY MAKING my way through a dense collection of James Baldwin’s later novels, I began to notice a recurring conceit. In his sixth and final work, Just Above My Head (1979), Baldwin’s narrator—in the midst of espousing his views with intense focus on love; Blackness in the United States, Africa, and Europe; and generational pain and healing—momentarily turns his attention away from his recollections to offer an explanation:

If one wishes to be instructed—not that anyone does—concerning the treacherous role that memory plays in a human life, consider how relentlessly the water of memory refuses to break, how it impedes that journey into the air of time. […] How then, can I trust my memory concerning that particular Sunday afternoon? Memory does not serve me, I had nothing to remember then.

The narrator, Hall Montana, would admit that an event’s specific place in time might have been muddied, unsure if it happened before or after the previous one. In other scenes, Montana interrupts himself to concede that some details slipped his mind, while others shone through in immaculate detail. Where do we go when our memory fails us, when our stories are full of holes, leaving parts of our own history inaccurate as if its true nature is shrouded?

Solace can be found in the concrete. That tenet rests at the center of Sly Stone’s 2023 memoir Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin). It’s a circular journey that opens and closes with the 80-year-old funk pioneer explaining his reasons for getting (and staying) clean from drugs, a decision he finally made following his fourth hospital visit for breathing ailments and fainting spells. Sandwiched between those organizing anecdotes is a frenetic meditation that sees the funk legend try to recount his life with varying degrees of depth, providing an unabashed—and often uneven and frustrating—look at each dark detail and celebratory instance that he has ever been a part of. Stone’s incredulous retelling of almost every happy accident and dangerous coincidence can make his musings feel like star-studded lucid dreams. But when he turns his lens inward, there comes an intense clarity, with his meditations on his motivations and creative visions manifesting in sustained moments of linguistic brilliance.

Stone starts with a metaphor, nimbly comparing his existence to a vinyl record, dropping you in the midst of his lyrical idiosyncrasies. Despite Ben Greenman’s role in co-writing the book, its sentences are unmistakably Stone’s: short, dripping with poeticism and wistful wisdom like sharp jabs to the jaw that cease to let up. He plays around with the idea of skipping around, treating each section of his life like different tracks, before looping back to start at the beginning: in Vallejo, California. The memoir opens with a prelude scene (briefly preceding the prologue’s account of his hospital visits) that witnesses Stone becoming unwilling to complete an interview for the book; it’s hard not to notice when he hunkers down to produce the most salient and forthcoming anecdotes—which are almost always attached to his burgeoning relationship with music. “There were seven of us, and the eighth member of the family was music,” Stone writes, immediately after running through the names on his family’s lineup. Gospel filled the house, his parents passing down the love of instruments and singing, permanently weaving music into the fabric of his existence. The very first vignette from his own life centers music not just as an important figure but also as both an internal compass that pushes him into new directions whenever needed and a motivator for self-worth:

We sang at home and then we sang in church. […] Once, I was up there, singing, feeding off the audience, hearing their shouts and applause, when pieces of the crowd broke off and women started running down the aisle, holding on to their hats, still shouting. Now I see that they were feeling the spirit in the song calling them toward the stage. Back then, I thought they were coming to grab me. I turned around, jumped off the table, and started running for my life.

I stopped running. I came back for the music.

Performance, in Stone’s telling, is a reciprocal act, where the service of bringing light and soul to those in front of him fuels which note he belts out, bringing him closest to euphoria when it all comes together, and tearing at his seams as it begins to falter.

From 1955 to 1963, Stone spent his days in high school and college forming bands with his brother Freddie and various friends that came and went, dabbling in the multiracial band makeup that would make Sly and the Family Stone—comprised of Stone brothers Sly and Freddie, Rose Stone (who joined a couple years after the band’s founding), Cynthia Robinson, Jerry Martini, Greg Errico, and Larry Graham—a distinctive force in the 1960s and ’70s. In each of those anecdotes reside little clues revealing how Stone would deal with being not only a Black man in the United States but also a Black male artist. The racial borders in Vallejo—where the population in 1960 was 80.4 percent white and 16.5 percent Black, and stringently separated due to housing redlining policies (now, Vallejo is 28 percent Hispanic, 23 percent white, 19 percent Black, and 23 percent Asian)—were just lines to Stone, ones he had no problem crossing. He would enter piano and guitar competitions, often winning—and often noting that the groups he competed against couldn’t stand losing to Black artists. But that instance arrives in Stone’s writing with such a limp impact that it feels as though it barely registered to him, as if the larger effects of racism and discrimination washed over him without a second thought. Soon after, he concedes that the diversity in the city wasn’t necessarily fair. “There was only one day when black people could swim in the public pool,” Stone writes. “That was Saturday. I remember going one day when everybody was white. I don’t recall anyone saying anything to me, and if they had I wouldn’t have listened. I could never get into that way of thinking. The water’s the same for everyone.”

The fervent and rambling recollections of Sly and the Family Stone’s ascension arrive with such vigor that it’s a miracle Stone included any other details from his life. His endless run of truncated sentences lands like a thousand paper cuts, even as some specifics of the memories of how the band formed slip to the wayside. Amid Stone’s tendency to produce hazy recollections, steadfast conviction underscores each description of what every original member brought to the table. Even in the early days, before their first gigs at Winchester Cathedral in Redwood City, Stone understood the magnitude of the band he had formed. “The band had a concept—white and black together, male and female both, and women not just singing but playing instruments,” he said. “That was a big deal back then and it was a big deal on purpose.” For a moment, there’s a recognition of the barrier-breaking act that his racially integrated and gender-mixed band was about to undertake. But those ruminations disappear in an instant, as though the monumental conception was merely an afterthought to the musical journey that followed, not a fundamentally equal aspect of the band’s legacy.

Stone lived through the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr.—he was by no means ignorant of the country’s “race problem” and social unrest of the 1960s and ’70s. But he asserts himself as someone who isn’t meant to provide the answers to our problems, just a man who could only express what he believed others were feeling. His general adherence to the “Golden Rule” tenet, where the reciprocity of kindness is the key to a peaceful society, makes some of his musings on the Civil Rights Movement and the strive for equality feel surface-level—something he even recognized, especially when juxtaposed against the value systems of others. He highlights his 1974 appearance on The Mike Douglas Show with his close friend Muhammad Ali. The legendary boxer was delivering verbal blows on social injustice; meanwhile, Stone recalled, “[w]hat was I doing but clowning and laughing? I made a case that what I was doing was entertainment, and that entertainment was an important part of the solution.” Regret about or any deeper reflection on that chasm between his and Ali’s original political sentiments doesn’t appear to be on Stone’s mind, causing the memoir to shift into a standard diary or journal entry. There seems to be just an appreciation that moment even existed.

Stone’s prose peaks in quality and substance as he provides accounts of the band’s rapid ascension during the late 1960s, flooding readers with the considerations that arose from trying to bounce back from a critically flopping debut (1967’s A Whole New Thing), fleshing out an album around a bona fide hit (1968’s Dance to the Music), building off your past to create a brand new thing (1969’s Stand!), and creating when you feel a darkness clouding the country and yourself (1971’s There’s a Riot Goin’ On). The musicality and wordplay of Stone’s language flows most freely when he drills into how tracks like “I Want to Take You Higher” developed—this one was the result of an evolution from the band’s first album. He rattles through the theory behind the lyrics and composition as if he’s trying to teach a master class on how to make a Sly Stone record. The stream of consciousness flow extends to retellings of the band’s iconic Harlem Cultural Festival and Woodstock performances, where more and more instances of interiority and reflection arise as the joy of performance seeps into his memories again. In one breath, he drops into a paragraph the lyrics the group would sing; then, in the next, he likens the energy to “[a] wave crashing onto the shore of the stage.” The euphoria of performance not only fueled him in 1969 but also strengthened his ability to recall in the current day, giving real life and feeling to the watershed concert in the band’s ascension.

Everything became bigger for Stone and the band after Woodstock—the social circles and superstardom, the venues and artistic expectations, and, particularly in Stone’s case, the drugs. Excess caused his life and existence to swell to a massive and untenable size, much akin to a dying star that can only manage to consume everything in its orbit. He lived as extravagantly as he dressed, filling his house(s) with dogs, guns, and people he couldn’t dream of remembering—with famous names being dropped without the urge to pick them back up again. Stone’s fame and pressure to create and write fueled his drug habit (with the cycle often working the other way as well) even before we reach 1971 and There’s a Riot Goin’ On, extending into the decades after. Stone employs an unemotional, almost sterile matter-of-fact tone when discussing how cocaine, PCP, crack, and pills entered his Bel Air mansion and hotel rooms. It’s the same forthcoming, stark detail that arrives when he discusses his relationship with music. Stone has zero qualms about sharing how he almost blew up a bathroom while freebasing, or how he pressured Grace Jones into trying crack at a party.

Stone’s penchant for accepting the darkness in his life (tax issues, multiple drug busts, and relationships ending due to death and burnt bridges) turns the later portions of Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin) into a melancholic churn. There’s a bubbling defensiveness about his reputation for missing and canceling shows in his later years, at times making it seem as though he’s primarily concerned with setting the record straight. But maybe that comes with age, a steadfastness in the way he lived. In a rare interview with The Guardian earlier this year, Stone stood pat: “I never lived a life I didn’t want to live,” he said.

Stone’s long road to recovery frames Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)—illness and addiction make it tough at age 80, but support from his former girlfriend Arlene Hirschkowitz and his daughter Phunne helped him stick with his decision to get clean after the fourth hospital visit. Reconciling with his family and mourning the deaths of people he called peers and friends pushed him to share his own perspective on events, even if many of the details and specifics are frayed. Early on, Stone writes:

The details in the stories people tell shift over time […] That’s what makes them stories. Telling stories about the past, about the way your life crosses into the lives of those around you, is what people do, what they have always done. Those people aren’t trying to hurt you. They’re trying to set the record straight. But a record’s not straight, especially when you’re not. […] Every time a story is told it’s a test of memory and motive.

Thank You is by no means a definitive accounting of everything Stone did and went through—it’s campfire fodder that causes you to lean over to the person next to you to ask, “Did that really happen that way?” A large part of you is just glad Stone was willing to tell it, and that you were there to listen.

LARB Contributor

Matthew K. Ritchie is a writer from Las Vegas, and holds a master’s degree in journalism from Northwestern University. He has written for Pitchfork, GQ, and the Chicago Reader, among other publications.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Wound Is Objective: A Conversation with Édouard Louis

Stephen Patrick Bell interviews Édouard Louis about his new book “Change.”

Through a Herne’s Eye: On Ursula K. Le Guin’s “Five Novels”

Brian Attebery offers a critical reflection on five of Ursula K. Le Guin's short novels, recently reissued by Library of America.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!