Epicurus for Our Time

Robert Pogue Harrison approaches Epicurus for different ways of looking at the problems of today.

By Robert Pogue HarrisonMarch 12, 2023

“THE WASTELAND GROWS,” wrote Nietzsche over a century ago. “Woe to him who hides wastelands within.” Since then, the wastelands have grown ever more indiscriminately, both within and without. Our social and spiritual lives wither on our cell phone screens. Our cities, habitats, and public arenas suffer from a blight whose causes remain obscure while the effects are all-too-evident. The “little garden” of the human spirit falls into disrepair.

The term “little garden” alludes to Ho Kepos, or the small privately owned garden where in 306 BC Epicurus started one of the most influential and long-lived schools of antiquity. He lived in darkening times similar to ours, when the public and political spheres of Athenian democracy had fallen into decay and degradation. Greek philosophers before him—starting with Aristotle—believed that human happiness was possible only within the polis and the activities of citizenship. Epicurus instead believed that happiness had to be sought far from the folly and factionalism of the public realm. That is one reason he founded his school just outside the walls of Athens.

Our age is badly in need of a strong dose of creative, revitalized Epicureanism, for Epicurus offers us a philosophy of how people can, on their own initiative, create little wellsprings of happiness in the midst of the wasteland. In our time, that would mean finding quiet but decisive ways to resist the molding and administering of private desires by capitalist surrealism; to resist the herd mentality and intellectual shallowness promoted by peer groups, opinion makers, and the cacophony of social media; to resist self-absorption in all its subtle and vulgar forms; and, above all, to resist the siren call of success. To resist, however, is not enough, and that is where Epicureanism, as a positive philosophy, comes into play.

Epicurean gardens flourish where like-minded people cultivate various social, psychological, and existential virtues that render life more beautiful, “sweeter” (hedys, sweet, the Greek root of “hedonism”), and more worth living; and whose cultivation amounts to a form of spiritual caretaking. These virtues include friendship, a supreme Epicurean value; conversation, the main ingredient of a meaningful friendship; an active life of the mind, which Epicurus understood as a nursery for the ideas that enrich conversation and make it pleasurable; suavity, or a certain agreeableness of manner and personal demeanor; and serenity, or inner calm and self-possession.

These Epicurean virtues are in short supply these days. Do we even conceive of them as habits and practices to be cultivated? Most of us believe that we should acquire and nurture friendships, yet how many of us believe that we must first learn the art of friendship, precisely by curating those other qualities that enrich the experience of friendship? In the ancient world, to be an Epicurean meant to commit oneself to a lifelong curriculum of self-improvement and souci de soi (“self-care”), a term made popular by Michel Foucault. By doing what it takes to become a more thoughtful, conversant, and appealing person, I become more fit for friendship. Friendship is, above all, a font of generosity.

As important as these social and personal virtues were for the good life, as Epicurus conceived it, even more important was the cultivation of three primary existential dispositions: hope, patience, and gratitude. Epicurus understood this trinity of virtues as a way of relating to time’s three dimensions. Let’s review them in turn, if only briefly.

Epicurus believed that anxiety about the future—especially the ultimate future of death—was the biggest impediment to human happiness. The future worries us, haunts us, and often torments us, since we can’t know exactly what it holds in store: a reversal of fortune, the loss of loved ones, disease, disaster. It comes at us blindly, and, more often than not, we await it with dread, despite the lure of its promised lands. Against such dread, the Epicurean cultivated an attitude of hope—hope that the prospect of happiness sown in the present will blossom in due time. Hope does not pine after a promised land. It brings to fruition an inner potential realized in time, turning death into a culmination rather than extinction of possibility.

Patience, in its tending to inner possibility, trusts the future to fulfill the dedications and efforts of the present. It transfigures our relation to the present by filling its days with the unseen fruit of things hoped for. To repurpose Stendahl’s definition of beauty, patience is a promise of happiness.

As for gratitude, it is the primary existential virtue that grows in the Epicurean humus. It is also the rarest, and the one most in need of daily care and nurturing, whether in Epicurus’s time or our own. We have a natural inclination to discount the blessings of the past and remain always hungry for more. “The life of the fool,” wrote Epicurus, “is marked by ingratitude and apprehension; the drift of his thought is exclusively toward the future.” This ungrateful “drift of thought” directed toward the future has little to do with Epicurean hope. Its apprehension is based not on patience in the present, nor on thankfulness for what has already been given, but on an anxious discontent whose tremors darken the future, obliviate the past, and unsettle the present. The ingrate relates to time as a source of privations rather than blessings, and hence is essentially gluttonous: “It is the ungratefulness in the soul that renders the creature endlessly lickerish of embellishments in diet.” Gratitude, by contrast, consecrates the past, sweetens the present, and becalms the future.

The Epicurean philosophy has almost nothing in common with the so-called “hedonistic” philosophy of “eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we die.” For Epicurus, pleasure was first and foremost the absence of pain, yet it was far more than that. It was a particular kind of “sweetness” that accompanied a state of serenity. Serenity in turn was the fruit of the virtues promoted by the Garden School. Toward the end of his life, Epicurus suffered a slow and painful death brought on by a bladder stone in his urinary tract, yet he faced both his pain and imminent death cheerfully, thanks to his lifelong cultivation of gratitude. On his deathbed, as he made clear in his letters to various companions, he derived an exquisite pleasure from his memory of those moments of fellowship and conversation he had feasted on in the past with friends.

Any gardener knows that hope, patience, and gratitude are the inner dispositions that sustain his or her activities. Hope sows the seeds, patience that awaits their burgeoning, and gratitude that bears witness to nature’s life cycles. Epicurus’s “little garden” was not only the setting for his school of philosophy; it was also an essential part of its pedagogy. The students at the school tended the vegetable garden daily in order to better understand the cycles of growth, decay, and regeneration, and to better understand how the Epicurean virtues—from friendship to serenity to gratitude—do not flourish naturally but call for constant care and vigilance if they are to thrive within the individual soul as well as the Epicurean community of friends.

Where the wasteland grows within, we relate to the present with impatience, to the future with despair, and to the past with ingratitude. In the wasteland, pleasure amounts to consumption, and happiness amounts to complacency. Consumption and complacency can get us through life, perhaps, but only care and cultivation will allow us to consummate life with the kind of attitude Epicurus and his followers aspired to, namely to take one’s leave of it as if after a feast: grateful for its abundance and not hungering for more. We, by contrast, live in an age of craving. While Epicurus may not be able to fully cure us of our cupidity, his philosophy of hope, patience, and gratitude, as well as of friendship, conversation, and the exchange of ideas, shows us another way of owning our mortality and becoming the gardeners of our own happiness.

¤

Robert Pogue Harrison is a professor of French and Italian literature at Stanford University. He is the author of five books, including Gardens: An Essay on the Human Condition (2008).

¤

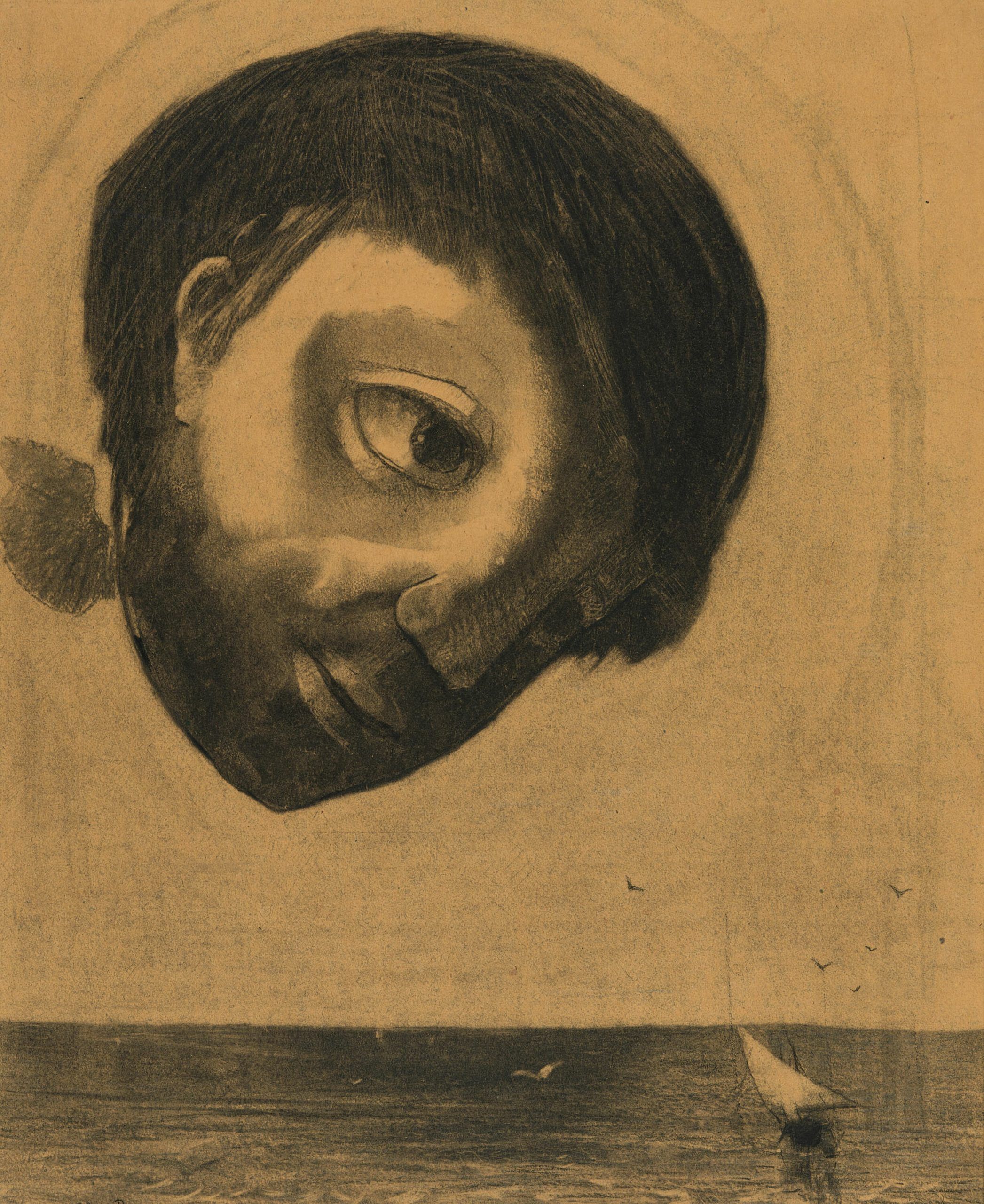

Featured image: Odilon Redon, Guardian Spirit of the Waters, 1878. The Art Institute of Chicago. David Adler Collection, www.artic.edu. CC0. Accessed February 3, 2023.

LARB Contributor

Robert Pogue Harrison is the Rosina Pierotti Professor of Italian Literature at Stanford University. He is the author of several books, among them Forests: The Shadow of Civilization (1992), The Dominion of the Dead (2003), and Gardens: An Essay on the Human Condition (2008).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Fashioning Death

Gwenda-lin Grewal examines the parallels between philosophy and fashion.

Does a Final Theory Exist?: A Conversation with Alan Lightman

Julien Crockett talks with Alan Lightman about his new book “The Transcendent Brain: Spirituality in the Age of Science.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!