Eighty Years of James Agee

Christopher Knapp looks back on "Let Us Now Praise Famous Men."

By Christopher KnappSeptember 1, 2016

Let Us Now Praise Famous Men by James Agee and Walker Evans. Mariner Books. 432 pages.

PER CUSTOM, BILL O’REILLY opened the July 12 installment of his show on Fox News with the warning that viewers were about to enter a “No Spin Zone.” The focus of that night’s program was the question of whether, as Donald Trump put it in a subsequent interview, “we have a divider as president.” A few nights earlier, O’Reilly had cited a Pew poll in support of the assertion that “the political divide in America is getting worse, with some folks descending into rank hatred,” and now, as evidence that President Obama indeed bore the ultimate responsibility for this development, he presented a brief clip in which Matt Finn, a Fox News correspondent who had been sent to a Black Lives Matter rally in St. Paul with no other agenda, O’Reilly would have us believe, than to report the protesters’ point of view, was “besieged” by a cursing mob.

What moments like this make bewilderingly clear is just how difficult it is, in so big a country, for us to understand each other — how successfully we’ve divided ourselves into choirs to be preached to. Our earnest attempt to remedy for this hopeless state of affairs is the convention of sending investigators into each other’s midst. This is how we end up with Fox News at a BLM rally, but also with David Foster Wallace on a cruise ship, Joan Didion in the Haight-Ashbury, John Jeremiah Sullivan at a Christian Rock festival, and, when the stakes are highest, George Saunders on the Trump campaign trail.

Journalists inevitably undertake such projects with a hypothesis in mind, whether consciously or not; the danger, even among the best practitioners of the form, is that the project might devolve into an elaborate exercise in confirmation bias. With the internet and social media in an advanced stage of adolescence, this danger is, if anything, only amplified: witness, for example, the false promise of one journalist’s live tweeted exposé of a Trump rally, which is no doubt a perfectly factual account of some truly monstrous behavior, but nonetheless offers nothing in the way of insight, nothing at all beyond the guilty pleasure of affirming the premise that Trump supporters are monsters and that we readers are not. “[Trump] has found the pulse of these ignorant, livid people,” the same journalist would later write in a published piece, “and is playing it like a virtuoso strumming an instrument.” At its worst, this kind of journalism exploits the power dynamic that exists between the reporter and the reported-upon, reinforcing the class alienation it purports to expose.

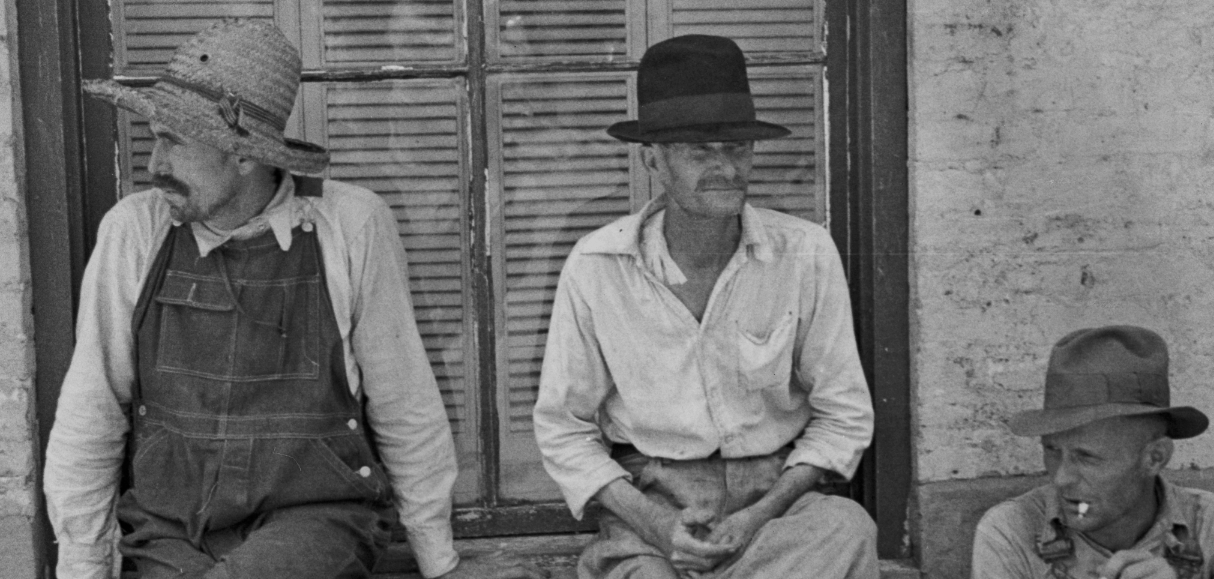

Eighty years ago this summer, James Agee wrote to his longtime friend and former grade school teacher, Father James Harold Flye of St. Andrew’s School in Sewanee, Tennessee, to say that he’d gotten the biggest break of his somewhat fraught career as a staff writer for Fortune magazine: a monthlong assignment to document the lives of white sharecroppers in the deep South, as part of the magazine’s “Life and Circumstances” series. Immersive journalism was by then a familiar practice, and whatever concerns may have existed about journalists’ conscious or unconscious preconceptions were dispatched by invocations of what James Aucoin calls the “‘ritual’ of scientific objectivity,” which had become central to the gospel of American news media. What Agee’s editor envisioned, the writer surmised, was a brand of muckraking — a self-congratulatory aestheticization of poverty that disguised itself as a call for reform. To Agee, this was the pinnacle of Northern arrogance, and he hoped to subvert it with something bracingly new. “Feel a terrific personal responsibility toward story,” he wrote to Father Flye, “considerable doubts of my ability to bring it off; considerable more of Fortune’s ultimate willingness to use it as it seems (in theory) to me.”

These were reasonable concerns: Agee and the magazine he wrote for were almost obscenely mismatched. He’d spent his entire intellectual life to that point in flirtation with outright Marxism; Fortune, meantime, had been founded six years earlier — in the immediate aftermath of the Wall Street Crash of 1929 — as the “Ideal Super-Class magazine” designed to “reach the greatest concentration of wealthy and influential people,” at a time when income inequality was as high as it would get in the United States until roughly Bernie Sanders’s first term in Senate. By the time he wrote to Father Flye to announce his big break, Agee had been on sabbatical from the magazine for seven months, recovering from his self-disgust. But the time off had been enough to restore his natural enthusiasm. As ambivalent as he was about the slick brand of magazine journalism that the Henry Luce publishing empire was built on, he was not only broke, but also desperately bored. To add another motivation, his editor, Robert Ingersoll, assigned Walker Evans to accompany Agee as photographer. For anyone who’s read the book that emerged from the assignment, it will come as no surprise to know that Agee later wrote of the moment Ingersoll offered him the story, “Every sense cleared about three hundred percent and stood up on its hind legs waving its feelers.”

It was in this spirit that Agee went south the following month; and that he installed himself in the homes of three families he judged to suit his purposes, whom he’d give the pseudonyms Gudger, Ricketts, and Woods; and that he spent the next five years refining and expanding (and expanding) upon his initial account of the experience, to the seething and profoundly strange final iteration of which he gave the peculiar, half-ironic title Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

¤

Smugness was the chief sin of the journalism Agee most despised — a vogue for “‘anthropological’ scrupulousness” that was a kind of bastard’s inheritance from the turn-of-the-century’s Progressive Era. “You cannot possibly honor what you patronize,” he wrote to Father Flye as he wrestled with his book. To Agee’s thinking, the journalistic principle most responsible for perpetuating this kind of patronization was the ruse of objectivity, which provided air cover for, among other things, the “lack of self-skepticism of all organized reformers and revolutionists.” He would have agreed with scholars like Michael Schudson, who have suggested that the ideal of impersonal, objective journalism, which developed to insulate news media from accusations of partiality, in fact insulates nothing so much as the status quo. It was as a matter of ethics, not of aesthetics, that Agee purported to suffuse his work with the self — not only with his personal perspective, but also with the whole of his personality.

Agee’s reservations about the prevailing best practices of journalism had crystallized for him two years earlier, when a piece he’d turned in on “The Great American Roadside” ran with photos by Margaret Bourke-White that he felt sensationalized the suffering he had hoped his writing would dignify. The fear of producing more work of the same order paralyzed Agee, and the considerable doubts he alluded to in his letter to Father Flye before his trip get full-throated expression in the first pages of the book. In a catalog of “Persons and Places” that precedes the main text, he lists himself as “a spy, traveling as a journalist,” and his discomfort in this role expresses itself in a kind of flailing hostility. In what the table of contents describes as a “preamble,” he expresses his contempt first and foremost for his employers, in terms worth quoting at length if only to furnish an example of one form of excess in Agee’s prose:

It seems to me curious, not to say obscene and thoroughly terrifying, that it could occur to an association of human beings drawn together through need and chance and for profit into a company, an organ of journalism, to pry intimately into the lives of an undefended and appallingly damaged group of human beings, an ignorant and helpless rural family, for the purpose of parading the nakedness, disadvantage and humiliation of these lives before another group of human beings, in the name of science, of “honest journalism” (whatever that paradox may mean), of humanity, of social fearlessness, for money, and for a reputation for crusading and for unbias which, when skillfully enough qualified, is exchangeable at any bank for money (and in politics, for votes, job patronage, abe-lincolnism, etc.) […]

The sentence continues in this vein. What he’s driving home is the contrast between Time Inc.’s motivations in commissioning a piece on rural poverty and his own motivations in accepting such a commission from an entity he and Evans count “among their most dangerous enemies.” And he regards the reader’s motivations for buying such a book with equal suspicion and contempt: to anyone who can afford to buy it, he suggests, it can only be of interest as a means of gawking at the misfortune of others, from a safe distance, or of reinforcing a kind of faddish liberalism. The cotton tenants themselves, of course, are spared the scorn, but not, despite his best intentions, the condescension: “these I will write of are human beings, living in this world, innocent of such twistings as these which are taking place over their heads.” In short, Agee was duly tormented by the thorny ethics of the entire enterprise. In that torment, he was well ahead of his time, and so left to navigate it on his own — resorting to vigorous handwringing, the harsh rebuke of the consumerist nature of journalistic institutions, the unequivocal idealization of his subjects, and the frequent lament that what he’s trying to say cannot be said.

“If I could,” he writes, “I’d do no writing at all here.” He settles instead for quite the opposite.

¤

Fortune held the story that Agee filed for a year before they released it. In the meantime, Agee’s ambitions for — and doubts about — expanding the piece grew ever more fervent. “Such a subject,” he wrote Father Flye, “cannot be seriously looked at without intensifying itself toward a centre which is beyond what I, or anyone else, is capable of writing of: the whole problem and nature of existence.” In 1937, Modern Age Press published You Have Seen Their Faces, Margaret Bourke-White’s collaboration with Erskine Caldwell on the precise subject of Southern sharecropping. Many of Bourke-White’s photos were elaborately staged, and captioned with fabricated quotations — “intended,” according to the preface, “to express the authors’ own conceptions of the sentiments of the individuals portrayed.” These conceptions ranged from merely insipid and clumsy to appallingly racist (e.g., beneath a photo of a black woman in her home: “I got more children now than I know what to do with, but they keep coming along like watermelon in the summertime”). For Agee, that book’s tremendous critical and commercial success was demoralizing to the point of paralysis: not only had he and Evans been scooped, but their material had also been turned into a monument of the precise sort of vain, toothless propaganda they hoped their own work would tear to the ground.

In 1942, after Let Us Now Praise Famous Men had finally been published by Houghton Mifflin, Lionel Trilling wrote in the Kenyon Review that it was “the most realistic and the most important moral effort of our American generation.” He accepted the fact that Fortune had refused to publish it five years earlier as evidence of its moral rigor: “the attitude of clear, cool investigation had been manifestly impossible,” he explained. So it is that in an early chapter called “Near a Church,” when Agee, enchanted by the aesthetic “goodness” of the church in question, runs after a young black couple in order to ask to be let inside: he startles them, reportedly, to the point of tears, which causes him, in turn, to convulse with self-reproach. In describing the scene, Agee is well aware that he’s holding the couple hostage to his guilt, as he struggles to find a graceful way to “relieve them of [him]” and let them be on their way. “In that country no negro safely walks away from a white man,” he writes, “or even appears not to listen while he is talking.” With clear, cool investigation into this moment being impossible, Agee strives instead for transcendent empathy. “I could not bear,” he writes, “that they should receive from me any added reflection of the shattering of their grace and dignity, and of the nakedness and depth and meaning of their fear, and of my horror and pity and self-hatred.”

As this passage demonstrates, Agee’s moral vision too often turned upon himself, and the cumulative effect is an exhaustive meditation not on social injustice, but on Agee’s personal guilt. To the extent that it opens space for readers to meditate upon their own guilt, such an effect is worthwhile. But what it so frequently crowds out is a practical reckoning of the systemic failures that give rise to this guilt. And Agee is at his best where such practical reckoning prevails. An early section headed “Money” gives a stark portrait of the structures that perpetuate rural poverty. He explains, for example, that Gudger owns almost nothing, renting his home, land, farming equipment, and all of his livestock from his landlord, Chester Boles. In plain, direct terms, Agee describes the cycle of debt, backbreaking labor, and repayment that leaves Gudger with only half of his crops from which to pay back “the rations money, plus interest, and his share of the fertilizer, plus interest, and such other debts, plus interest, as he may have incurred.” What remains, after settling doctors’ bills, are earnings that only in rare years amount to a positive number. Such collections of facts are among the most affecting and morally forceful parts of the book. That Agee reserves this moral force for his protagonists — Southern whites living in poverty — can’t be entirely excused by the narrowness of his original assignment. In one of the most active lynching states in the country, how hard would it have been, for example, to explicitly connect the scene with the startled couple to the broader context of their fear, or even to the casual, unrepentant racism he’s only just finished describing without comment in the preceding chapter.

¤

For decades, it was assumed that the report Agee filed was rejected on the reasonable grounds of its outrageous aesthetic indulgence. Until recently, a copy of that report was not available to compare against the book it eventually became. But in 2010, the James Agee Trust found a copy of the complete typescript as Agee submitted it to the editors at Fortune. In 2013, this manuscript was published under Agee’s original title — Cotton Tenants: Three Families — by Melville House, in cooperation with The Baffler. It contains no hint of aesthetic indulgence. Rather, it is a work of breathtaking journalistic rigor, composed almost entirely of the sort of lucid reporting that characterizes the best parts of the book.

Still, the most profound fault of Famous Men — what Trilling deemed its only fault — is original to that submitted typescript: a failure of moral clarity. Agee was descended from poor Southern farmers, and his elite Northeastern education rendered him instinctively protective of Southern whites and consciously romantic not only about the South and its culture, but also about poverty itself as a kind of state of grace, untouched by the corrupting influence of privilege. He described this attitude as a form of “inverted snobbery […] an innate and automatic respect and humility toward all who are very poor.” Take, for example, Agee’s long description of the animal life on the families’ farms. He gives a clear-eyed account of their inveterate cruelty as well as passing reference to their inveterate racism, but then subverts that clarity with the following assessment:

Here I can only say that in the people of this country you care most for, pretty nearly without exception you must reckon in traits, needs, diseases, and above all mere natural habits, differing from our own, of a casualness, apathy, self-interest, unconscious, offhand, and deliberated cruelty, in relation toward extra-human life and toward negroes, terrible enough to freeze your blood or to break your heart or to propel you toward murder; and that you must reckon them as “innocent” even of the worst of this; and must realize that it is at least unlikely that enough of the causes can ever be altered, or pressures withdrawn, to make much difference. [italics mine]

An example of the offhand cruelty he so readily forgives is the Gudgers having named a kitten “Nigger”; in a footnote, Agee offers defensively, “My apologies to the more strict left-wingers: the name is Negro.” Whether it’s occurred to him how the name might strike, for example, the black couple whose apparent fear of him caused him so much anguish earlier in the book isn’t entirely clear. But by making it a matter of intellectual and moral relativism, he opens the Gudgers to the very charges of backwardness against which he hopes to defend them.

Likewise, Agee’s concern that the book dealt in ideas and was written in a language that was bound to be inaccessible to its subjects — an act of “spiritual burglary” — underscores the condescension implicit in his idealization. In Doing Documentary Work (1998), Robert Coles (who served for a time as the James Agee Professor of Social Ethics at Harvard), recalls marching from Selma to Montgomery in 1965, as locals gathered at the roadside to hurl stones and epithets. A fellow marcher, he says, noticed how near they were to the place Agee had visited 30 years before. “Some of those same people,” the man remarked, “could be right there on the road, calling us every name you can think of.” It would be hard to reckon their lathery hatred as the perfect innocence Agee claimed for them.

In his description of the Gudgers’ treatment of their livestock, and of the cruelty that underlies their casual racism, Agee is well aware of a complex status anxiety at play; in the few scenes in Famous Men involving African Americans, he invokes the bigger picture of race relations in the United States only glancingly. Elsewhere he engaged the matter head-on, and in doing so revealed his considerable confusion: in letters to Father Flye, he argued passionately, on the one hand, for the natural right not to be discriminated against, but in nearly the next breath agrees that the matter should be resolved in the consciences of Southern whites and not in federal legislation. In an unpublished article addressing such legislature, Agee defends Southern whites as “trapped […] now more seriously and more permanently than the Negro is trapped […] in passions of convictions and of reactions whose intensity no Northerner can be qualified to even guess at.” In a version of the same piece, he claims:

that some of the finest personal relationships possible can develop between whites and Negroes … and that virtues are developed in some Negroes with that predicament who will rest alone those excellent friendships, when the Negro has won his equality.

What those virtues might be he doesn’t say, and the fact that he never published the article may indicate that he thought better of the sentiment. Nonetheless, the draft testifies to the problems inherent in Agee’s supposedly moral approach.

¤

This year, in March’s GOP primary contest in Alabama, Donald Trump won Hale County with 52 percent of the vote. Since Agee’s visit, according to US Census data, the county’s population has fallen by about 40 percent, but its white population has fallen only by about eight percent — that is, there are about 11,000 fewer people, but not even 600 fewer white people than there were in 1936. If these statistics map onto a narrative in which the United States has left Southern whites behind, they also represent the fact that Southern whites were responsible for nearly 4,000 lynchings of African Americans between 1887 and 1950, many of which, according to a 2015 report compiled by the Equal Justice Initiative, were carried out in response to perceived transgressions of racial hierarchies: infractions such as bumping into a white woman, or failing to address a police officer as mister.

Eighty years after the fact, the hypothetical grown-up Gudger and Ricketts and Woods children, whom Coles imagines throwing rocks along the road from Selma, now have hypothetical children of their own; if it’s a little bit repulsive for Agee’s detested armchair liberals to automatically assume they’re out beating up protesters at a Trump rally, that doesn’t logically preclude the possibility that they’re out beating up protesters at Trump rallies. It’s easy to imagine them — in the comments, say, beneath a 10-minute video of Philando Castile’s death in which Diamond Reynolds can be heard addressing the officer who’s just shot her boyfriend four times as “sir” — assuming a posture of victimhood, and snarling that all lives matter. We’re not in danger, that is, of idealizing them the way that Agee did. This isn’t to say that any of the individuals Agee met in 1936, or any of their descendants, are guilty of anything on quite this order, or that it’s ever fair to assume a set of behaviors and attitudes in individual members of any given demographic. But it’s worth wondering what Agee would come back with if Henry Luce sent him to cover Trump supporters, or Brexit voters, or any of a host of nationalist movements all over Europe — whether he’d ask us to reckon them innocent of a worldview that lashes out violently against any perceived encroachment on their supremacy.

Still, if George Saunders’s recent report from the Trump campaign trail is any indication, this kind of documentary work, when undertaken in good faith, is still the best tool we have for listening to each other’s choirs. Agee wasn’t the first immersive journalist, but he was one of the first to give so much thought to what that good faith would look like. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men has been a touchstone in countless treatises on journalistic ethics, but of course it is its own treatise on journalistic ethics — searching and flawed, but indispensable.

¤

LARB Contributor

Christopher Knapp is an MFA student in University of Virginia’s fiction program. His work has appeared in the Paris Review Daily and the New England Review.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!