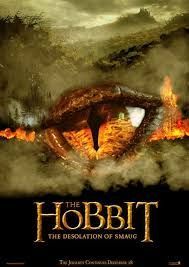

Dragonfire and Ruin, or King Under the Mountain

The ultimate joy of The Desolation of Smaug is in watching its many moving parts.

By Michael NordineDecember 23, 2013

MY FRIEND NATE BELL once told me that, were he confined to a desert island and forced to choose between books and movies as his sole source of entertainment, he'd opt for the former. This came as something of a surprise: Nate and I were in the same film studies program, and this conversation almost certainly took place after the first day of class. If pressed, I'd likely choose the same, though the decision wouldn’t be easy. Though I was a reader long before I was a cinephile, the seventh art has overtaken not only literature but everything else in my life over the last several years. The whole notion of choosing between these two passions is, thankfully, one that will never be realized, but it's one that The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug nevertheless brings to mind. Peter Jackson's earlier J.R.R. Tolkien trilogy, The Lord of the Rings, is to me what Star Wars was to many in my father’s generation: the stepping stone to my cinephilia. It's also an adaptation of a literary trilogy that I've still never read.

This isn't exactly for lack of trying. I started The Hobbit in seventh grade but didn't make it past the first 100 pages; ditto The Fellowship of the Ring, which I attempted to read shortly before the film adaptation arrived in theaters in late 2001. Both aborted attempts are the source of much shame, especially in light of how easily rectified they would be today. With only one movie remaining, the thought of finally catching up with the books in time for There and Back Again represents a kind of closure that’s as appealing as it is daunting.

This fantastical milieu has proven worth returning to time and again in part because it's grown along with the series. Fairly welcoming at the beginning of An Unexpected Journey, Middle Earth grows just a little darker and more menacing each time a monarch makes a grim pronouncement or a skirmish breaks out between warring races, both of which happen often in The Desolation of Smaug — the world of hobbits, elves, and others is slowly shifting from the sunny one Bilbo Baggins left behind to the war-torn land his adoptive heir will one day come to know. At once familiar and otherworldly, this is an environment in which riddles, talismans, and mystical keys take on life-or-death importance; where graceful, statuesque elves tussle with stocky, pugnacious dwarves; and where notions of destiny and forbearance weigh heavily on several major characters. At this point it may go without saying that the battles these competing elements result in are quite awe-inspiring on a sensory level. More remarkable is Jackson and his co-writers’ ability to make even the most outlandish creatures’ struggles feel distinctly human and further distinguish these films from their genre ilk. The once-marginalized elements of high fantasy are now the stuff of human drama, which is an easy feat to take for granted now but bears repeating nonetheless.

The main plot thread finds Thorin Oakenshield, the dwarf who would be king, attempting to fulfill his filial legacy by returning to Erebor, the “Lonely Mountain,” in order to wrest the Arkenstone from the dragon Smaug. Bard, a bowman of ill repute, has a similar stake in taking down the fire-breather: his ancestor Girion came close but ultimately failed to do so a full 174 years earlier, leading to much destruction and sorrow in the town of Dale and elsewhere. Ostensibly the protagonist in all this, Bilbo is often relegated to Thorin's sidekick as he helps him recover the glimmering family heirloom that now resides in Smaug's mountain lair and restore not only the dwarf kingdom but also his family's good name.

That the two Aragorn surrogates will eventually settle their differences and come together to fell the beast (whether in this installment or the next) is essentially a foregone conclusion, but the speed and economy with which Jackson sets up this tension is a sight to behold nevertheless. For all the complaints that stretching one book into three long movies was utterly unnecessary, let it not be said that The Desolation of Smaug’s pacing is laborious in the slightest. Its pacing may actually be the most breathless of the entire saga thus far and, considering the abrupt manner in which it concludes, I was genuinely surprised to have reached the end.

“When did we allow evil to become stronger than us?” Evangeline Lilly’s created-for-the-movie elf Tauriel asks the more seasoned Legolas midway through the film. She’s gone after a group of dwarves in order to assist them in a battle that, according to the elf king Thranduil, is not their own — a contention Legolas holds as well. “It’s not our fight,” he tells her quite directly; “it is our fight,” she responds. This notion of collective responsibility factored heavily into the earlier trilogy as well. Recall, if you will, the exchange between Treebeard and the hobbits in which the former claimed not to be on anyone’s side in the coming war, as nobody was on his, and an aghast Merry crying out, “But you’re part of this world!” Though this could be read as a retread of that same theme, it registers as sincere. Jackson’s adaptations of Tolkien’s books are very much about the power of good overcoming evil and the fact that, in order for this to occur, the good must not sit idly by.

The desolation of Smaug (or any other malevolent force) is what keeps townsfolk shaking in their boots, willing to live under the thumb of a vainglorious despot rather than rise up against him and upset the established order. This, more than anything else, is why the hobbits — seemingly the least impressive of Middle Earth’s myriad creatures — are also the most important: they’re unexpectedly courageous. This is a world in which one’s race (read: elf or dwarf or man or hobbit) and ancestry color everyone else’s perception of them, and yet it’s also one in which good deeds and valor have the power to quash those preconceived notions.

The film’s main draw, namely the dragon of the title, may also be its least kinetic element. A curiously verbose serpent, Smaug spends a great deal of time chewing Bilbo out — for being a liar, for being a would-be thief, for being the dwarves’ pawn in their attempt to reacquire the Arkenstone — before finally trying to chew him up and bring about more desolation. Only in these scenes does the movie appear to drag at all. Still, when Smaug finally does take flight and start breathing fire, it’s a thing of terrible beauty on par with the most wondrous set pieces Jackson has ever put together. The ultimate joy of The Desolation of Smaug is in watching its many moving parts — a dragon here, a roving band of orcs there — link together with near-seamless grace, and Jackson and his team pull it off capably. These three Hobbit movies may never escape comparisons to the One Trilogy to Rule Them All, and it’s even clearer now than it was in An Unexpected Journey that they’re unlikely to reach the same epic heights. Taken on their own terms, however, they’re a worthy successor (or predecessor, as it were) to Jackson’s first foray into Middle Earth. I’ll have to get back to you on whether or not they also do justice to the book.

¤

LARB Contributor

Michael Nordine, a Los Angeles–based film critic, is a regular contributor for LA Weekly and the Village Voice.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!