Down to the Wire in Old Shanghai: On James Carter’s “Champions Day”

Taoyu Yang reviews James Carter’s “Champions Day: The End of Old Shanghai.”

By Taoyu YangNovember 17, 2021

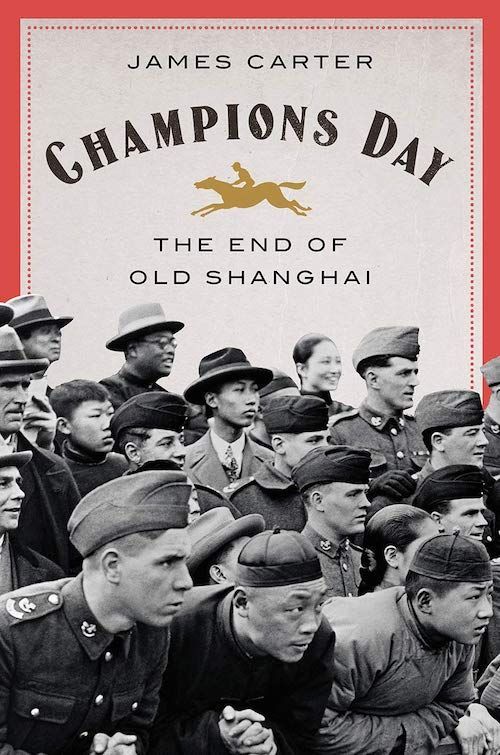

Champions Day: The End of Old Shanghai by James Carter. W. W. Norton & Company. 352 pages.

ON OCTOBER 1, 1952, three years to the day after the Chinese Communist Party headed by Mao Zedong took national power, two new spaces known as “People’s Square” and “People’s Park” were opened in the center of Shanghai. The Square became the site of annual October 1 National Day parades and other state rituals of the People’s Republic of China. The Park provided recreation choices for all. They were also both treated as symbolizing just how different the socialist “New Shanghai” of the present was from the capitalist and semicolonial “Old Shanghai” of the late imperial and Republican eras. The Square stood on the grounds that had been used for horse racing during treaty-port times (the period from the 1840s through 1940s when the city was divided into foreign-run and Chinese-run sections), and the contours of the old course shaped the plaza’s layout. The Park stood on land whose most impressive feature was an elegant building that housed the Shanghai Race Club, off-limits during much of its history to all Chinese and largely the preserve of European and American men. It is the prehistory of the Park and Square, when they were sites of exclusion and privilege rather than People’s spaces, that is the focus of James Carter’s Champions Day, a lively work that uses the story of horse racing and the events of a single day at the races in the early 1940s to provide a panoramic look at a colorful city on the cusp of a dramatic transformation.

Carter has written two previous books on China’s past, but this is his first venture into the curious and complicated world of Old Shanghai. While racing is typically perceived as a sporting event associated with gambling and grand spectatorship, Carter uses it as a lens through which to examine many aspects of Shanghai’s social, cultural, and political past. He claims that “the Race Club represented the cosmopolitanism and excitement, as well as the racism and oppression, of a unique place,” and he uses vignettes and character sketches to illustrate what he has in mind. The result is a work rooted in archival digging and scholarly concerns — no surprise as the author is a professor of history at Saint Joseph’s University — yet one that offers some of the pleasures afforded by historical novels.

Champions Day consists of four interrelated parts. The first documents Shanghai’s history prior to the Japanese invasion in 1937, offering a brisk yet thorough account of the city’s transformation from a secondary commercial center of mostly regional importance (though with some ties to maritime Asia) to one of the world’s greatest urban centers. The second focuses on the history of racing during the earlier years of the Japanese occupation of Shanghai. Commonly known as the “Lone Island” period, this era saw those parts of the city with ties to Western powers cut off from the Chinese-run sections of Shanghai run by officials who had to answer to Tokyo. By juxtaposing the devastated state of the Chinese-governed district with the relatively peaceful situation in the International Settlement, an enclave in which British merchants had long been and remained important wielders of power, Carter shows that racing, along with other economic, social, and cultural activities, largely went on much as usual in the foreign-controlled zone, as the areas around it were ravaged by war.

Then comes a third part that is the centerpiece of the book and worth lingering on here. In this section, Carter analyzes a trio of events that occurred on a single day — November 12, 1941. In one part of the city, a large crowd of people gathered to observe the birthday of Sun Yat-sen, the founder of the Republic of China. In the French Concession, an enclave headed by an official who answered to Paris that bordered the International Settlement, about 20,000 people attended the funeral of Liza Hardoon, “the wealthiest woman in China” and widow of Silas Hardoon, a Baghdadi Jewish businessman. Neither of these events, however, garnered as much attention as the Champions Day in the International Settlement, where tens of thousands of Chinese and foreign spectators watched the year’s most decisive race. Little did they know that this day “marked the end of the Shanghai Race Club as the center of a world,” a world where Western power prevailed.

The concluding part of the book describes the end of racing in Shanghai and the start of the processes that transformed the course and the club into People’s Park and People’s Square. Although horse racing continued in various forms after the International Settlement succumbed to the Japanese authorities, the takeover of Shanghai by the Communist Party in 1949 signaled the formal end of the most popular sporting event of treaty-port times.

Even though Champions Day is clearly geared toward a more general readership, Carter weaves some engaging academic arguments into the book. One idea that may interest specialists is how Carter conceives of the category of “Chinese Shanghailanders,” adding a twist via the opening adjective to a term often reserved for people of foreign descent. Chinese Shanghailanders, in his view, were a product of Shanghai’s unique racial and sociopolitical dynamics — “a hybrid Chinese-Western society — under Western leadership […] but with Chinese participation.” They were usually Western-educated, bilingual, and conversant with European and North American habits and institutions. They certainly did not experience daily oppression, but they nevertheless had to operate under the framework of racism and imperialism that underpinned nearly all aspects of Old Shanghai. What characterized this interstitial group, Carter suggests, was a fundamental contradiction: they “reject[ed] and often criticiz[ed] the racism that excluded them from full participation, but [were] unwilling to jeopardize the privilege […] that China’s Western ties afforded them.”

Another critical intervention that Carter makes concerns breaking the history of “Old Shanghai” down into periods. Scholars have conventionally designated 1937 and 1941 as two critical historical junctures: the earlier year signaled that Shanghai began to be embroiled into a nationwide, all-out military conflict with the Japanese Empire, while the latter marked the end of Western privileges in Shanghai as Japanese troops occupied the city’s foreign-administered areas. Such a clear-cut periodization, according to Carter, cannot be applied to the history of racing and the Shanghai Racing Club, as the sport’s story straddles these arbitrary temporal divides. Under Japan’s New Order, racing continued, albeit with a much smaller audience. “[T]he races,” Carter argues, “symbolized the stability and status quo that Japan wanted to project.” Even after the Communist Party took control of the city in 1949, after a four-year period of Nationalist Party rule, the memory of the Shanghai Race Club has lived on. It has served as a useful propaganda tool to demonstrate that, unlike preceding regimes, the Communist Party has been able to single-handedly “restore to China the dignity and power of a great nation.”

Just as the book’s main characters constantly navigated across Shanghai’s Chinese and Western spheres, Carter, too, juggles between telling gripping stories and advancing serious historical arguments. As with many books that aim to reach both academic and general audiences, this can be a difficult balancing act to pull off, but Carter does a wonderful job of combining rigor with entertainment. Different readers will likely appreciate different aspects of Champions Day. A serious, historically minded reader will come away most impressed by Carter’s deep knowledge of modern Chinese history and dedication to thorough research. A reader looking for light reading over an international flight, by contrast, will more likely focus on Carter’s fluent prose and the memorable quotes and phrases that enliven the volume.

It is not a thesis-driven work, but if we wanted to pin down Carter’s main claim about the connection between Shanghai’s past and present, the world of the Racing Club that excluded most of the city’s people and the world of the People’s Party, it would be the following sentence: “This city, once run by foreigners and distinctive because it was Chinese, is now a Chinese city distinguished by its foreignness.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Taoyu Yang is a PhD candidate at the University of California, Irvine. His research is centered on the history of the multi-imperial dimensions in Chinese treaty-port cities, with a particular focus on Tianjin and Shanghai.

LARB Staff Recommendations

On the Chinese Cultural Revolution: Thought Exercises for the 21st Century

LARB presents a conversation with four scholars on the Chinese Cultural Revolution: Lingchei Letty Chen, Nan Z. Da, Frank Dikötter, and Jie Li.

Ballet in the City: Jewish Contributions to the Performing Arts in 1930s Shanghai

How European Jewish refugees brought ballet to China.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!