Dissolving Margins

Sarah Chihaya explores the edges of Jillian Tamaki's "Boundless."

By Sarah ChihayaSeptember 2, 2017

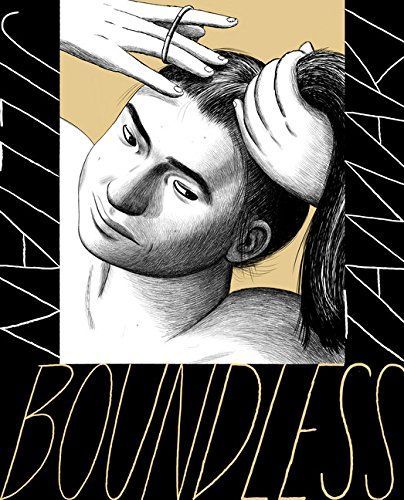

Boundless by Jillian Tamaki. Drawn and Quarterly. 248 pages.

I CAN’T SEE the word “boundless” without thinking of Juliet’s declaration in Act II of Romeo and Juliet:

My bounty is as boundless as the sea,

My love as deep; the more I give to thee,

The more I have, for both are infinite.

Juliet attributes to herself an endless generosity of feeling, a gift that renews itself through the act of giving. Skimming along the surface of this passage, “boundless” suggests miraculous capaciousness and plenty. Underneath this, though, a current of vulnerability runs through the word. After all, something or someone without bounds can either expand to embrace the infinite, or dissolve into and become lost within it.

Jillian Tamaki’s new short story collection, Boundless, drifts in the margin between these possibilities. The short comic on the back cover is perhaps the best introduction to the unsettling yet oddly exhilarating vignettes that unfold in this liminal space. In it, a motivational speaker tells a bemused audience about her decision to break down the constraints of conventional social being and embrace bad feelings:

For the last nine months I have let myself feel pain. I allow it to consume me fully and study its shades. Sadness can incapacitate me for weeks at a time. I’ve consumed nothing but salted peanuts and coffee today. Living in this state of instability is terrifying. I’ve never been more miserable. But I’m real. For the first time in my life I’m real! Haha!

The punch line comes from the audience: we might agree as a listener mutters to her friend, “This lady is so screwed” — and then again as the friend responds, “She makes some good points though.” To be really real, in both the shifting worlds of Boundless and our own everyday world, is to open oneself generously to the totally ordinary, totally exceptional terror of being. Haha! indeed.

¤

The easiest way to read Tamaki’s title is formally: Boundless is a book that plays with the malleable conventions of graphic storytelling. The portrait orientation of its first piece, “World Class City” — a dreamlike semi-narrative that slips back and forth between pop lyric and lyric poem — demands that the reader turn the book sideways, while the abstract bodies and plants it depicts bleed across generous two-page spreads and, in a couple of cases, over page turns. The final section, “Boundless,” mirrors this vertically oriented, panel-free format, as a menagerie of urban animals flit and swoop across its sparse pages, narrating their nonhuman lives with deadpan panache. The stories contained between these bookends require the same readerly dexterity. Even when she works within the constraints of panels and gutters (which she often abandons in favor of borderless panels, backgrounds that are either overfull or hauntingly vacant, and splash pages), Tamaki’s layouts are kinetic, fluid, and unexpected. Her style is similarly mobile, as each of these nine stories articulate their own distinct idioms of color and line.

Yet this formal play serves more than aesthetic ends. The book’s eddying images and narratives visually enact the thematic questions of personal boundary and boundlessness that Tamaki’s half-melancholy, half-funny prose explores powerfully — namely, what crosses the margins between the internal and external self? Between that self and others? Between the self and the world?

The world outside the self takes many forms here, both human and nonhuman. In the book’s pages we meet internet cultures only slightly creepier than our own, obsessive fandoms and conspiracy theorists, domestic settings made uncanny by alarming shifts in scale or by infestation. Tamaki gives this world shape in pages swarming with mysterious plants, lines of code, and abstract figures. The odd encounters she stages between her individual protagonists and their environments are at once frighteningly alien and recognizable. We read familiar social anxieties and personal fears into them, dissolving still more boundaries — between the quotidian and the exceptional, fantasy and reality, humor and fear. In “The Clair-Free System,” for example, Tamaki renders conventional narratives surrounding female standards of beauty both eerily anxiety producing and absurdly comic. The story pairs a banal script for an Avon-like cosmetics selling scheme with abstracted, 1970s horror-inflected occult images, and includes what might be the funniest page of the book: a chanting coven of longhaired, long-skirted women overlaid with the incantation, “A cleanser, a toner, a moisturizer.” The overall effect is a weirdly stirring ambivalence — a blend, perhaps, of the sadness that undergirds the false promises of the beauty racket with hysterical recognition of their utter ridiculousness.

¤

Last October, a Tamaki illustration graced the cover of The New York Times Book Review, accompanying Elaine Blair’s review of Elena Ferrante’s Frantumaglia. Against a creamy ocher background, a multitude of female figures move through city streets. They might be part of a fractured, single cityscape, or specters from different times — or, given Tamaki’s interest in quilting and textile art, a scrap from a repeated toile pattern. Revisiting this piece, with its figures that coexist and collide and meld into each other, a subtle overlap between Ferrante and Tamaki’s projects is suddenly visible. It occurs to me that Tamaki’s ambivalent sense of boundlessness, with its range of ecstatic and frightening connotations, recalls a sensation that Ferrante attributes to the character Lila in her Neapolitan Novels: the uncanny experience of “dissolving margins.”

The thing was happening to her that I mentioned and that she later called dissolving margins. It was — she told me — as if, on the night of a full moon over the sea, the intense black mass of a storm advanced across the sky, swallowing every light, eroding the circumference of the moon’s circle, and disfiguring the shining disk, reducing it to its true nature of rough insensate material. Lila imagined, she saw, she felt — as if it were true — her brother break […] something violated the organic structure of her brother, exercising over him a pressure so strong that it broke down his outlines, and the matter expanded like a magma, showing her what he was truly made of […] she had the impression that, as Rino moved, as he expanded around himself, every margin collapsed and her own margins, too, became softer and more yielding.

A kindred phantasmagoria threads through Tamaki’s work, in Boundless as well as her earlier books. Like Lila’s description of her vision, Tamaki’s dissolving figures are both abstractly aestheticized and viscerally physical. Readers of her 2015 SuperMutant Magic Academy might think of the recurring character Everlasting Boy, an immortal teen whose endless cycle of violent disintegration and regeneration expresses profound melancholia through macabre physical comedy. In Boundless, though, as in Ferrante, the quotidian danger of dissolution is intimately linked to the experience of being a woman in the world. Scrutiny — by oneself, by others — is a main factor in the wildly varied processes of dissolution and disappearance revealed here.

This is rendered most clearly in the casually dismissive tone of “Darla!,” the tale of a short-lived pornographic sitcom. While the story abounds in close-up images of the beautiful star’s face and body, her voice is markedly absent from the narrative. The first-person narrator, a smug male showrunner delighting in his post hoc internet fame, condescendingly notes that he doesn’t know (or care) what happened to Darla herself: “Hopefully married to a nice guy with a couple of kids. Sweet girl.”

A more abstract illustration of female disappearance comes in “Half Life,” which opens with a much-desired compliment: “Have you lost weight? […] You look great!” The subject of this compliment, Helen, has indeed lost weight — but then she shrinks and shrinks uncontrollably until she drifts out on an air current, and is inhaled by a neighbor’s dog. Yet this disappearance is somehow not the end of feeling. It is at once horrifying and comforting to find that dissolution is not annihilation. Indeed, disappearance — either into the world, or from it — is framed as a kind of desirable sublimation in some of these stories, notably “1.Jenny” and “Sexcoven.” This pleasurable disappearance is another disconcertingly ambivalent impulse that quietly reverberates through Boundless’s gentle but persistent interrogations of female desire and agency.

It turns out that the “dissolving margins” of Lila’s vision are related to her chronic migraines — a condition that feels, like so many things in Ferrante, made up of equal parts gritty realist detail and symbolic abstraction. A similarly osmotic sense of interpretation circulates through Tamaki’s work. In her stories here and elsewhere, the barrier between allegory and realism is an invisible, permeable membrane. We see this tendency perhaps most clearly in “bedbug,” in which the pest seems like a clear and easy metaphor for the narrator’s guilt following an affair, and the objects in the infested household become stand-ins for a marriage examined. It’s impossible for the reader to escape the always-visible symbolism of the always-visible bedbug bites, as Tamaki’s words and illustrations summon up the anxious perseveration provoked by both infidelity and infestation. Yet the latter is not simply a figure for the traumatic aftermath of a meaningless affair. The story is just as much a profoundly realistic tale of the equally traumatic aftermath of a bedbug invasion. It thus has the curious effect of being at once overtly metaphorical and a 100 percent literal account, a narrative in which surface and depth — and in the book’s visual idiom, background and foreground — are indistinguishable.

In this light, the publisher’s blurb on the inside flap of Boundless, which optimistically proclaims that Tamaki’s book “is at once fantastical and realist, playfully hinting at possible transcendence,” feels incomplete. This description only gets at half of what is so remarkable about the quietly weird, unhinged worlds of Boundless. What’s truly arresting about the book is how its strange episodes float in the half-visible, shimmery cusp between deeper meaning and banality. It’s this delicate liminality that allows Tamaki’s odder scenarios, which in hammier hands might seem too self-consciously trippy, to communicate a subtle, intimate sense of the dangers of everyday personhood. While Tamaki’s stories are, for lack of a better word, small (in scope and length), they gesture to unsettlingly big questions. Is there a distinction between being a particular self and being particulate matter? Does the deepest fulfillment come from the boundedness of the distinct self, or from the diffusion of the self into the boundlessness of the wide world?

Of course, Boundless doesn’t offer any decisive answers to these questions. Its final sequence of spreads instead enacts a comic exasperation with the book’s heavy-duty philosophical inquiries via a kind of metatextual slapstick. In this sequence, an irate reader slams the book shut on its last narrator, an angst-ridden, Hobbes-reading housefly.

Jillian Tamaki, Boundless, pp. 238-243

This half-seen reader is yet another of Tamaki’s unbounded subjects, uncontained by even the extended frame of the two-page spread. She is perhaps a companion to the partially visible figures from the book’s opening movements: the cover’s cropped close-up of a woman pulling her hair into a topknot, and especially the two similarly page-exceeding figures that bookend “World Class City,” peering curiously into the pages of narrative. We might choose to read these figures as textual doppelgängers for the capital-R reader, uncontained, agential, half inside and half outside the book — or we might not. Either way, even after this cheekily literal act of closure, Tamaki’s inextricable tones of dark humor and oddly bright sadness linger with the reader, uncontained by the arbitrary limits of the book’s covers. Both, it seems, are infinite.

¤

LARB Contributor

Sarah Chihaya is an assistant professor of English at Princeton University. She is one of four authors of The Ferrante Letters, and is a senior editor at LARB.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Elena Ferrante: The Mad Adventures of Serious Ladies

GD Dess considers the complex female identities at the heart of the Neapolitan novels of Elena Ferrante.

Monster, Monster, On the Wall

Lily Hoang reviews Emil Ferris's "My Favorite Thing Is Monsters."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!