Dark Was The Night, Cold Was The Ground

A short story by J.D. Daniels from the LARB Weather Issue about camping in the snow, shoveling snow, and dreaming of Death Valley.

By J. D. DanielsJanuary 12, 2020

This piece appears in the Los Angeles Review of Books Quarterly Journal: Weather, No. 24

To receive the Quarterly Journal, become a member or purchase at our bookstore.

¤

“My poor son, that friend of yours is an idiot,” my father said to me when Bloch had gone. “My goodness! He can’t even tell me what the weather’s like! Why, nothing is more interesting!” — Proust

Early last night there was a ring around the moon. Low and burning yellow, it peered at us through trees. If you were not disposed to see a burning yellow eye in a gauzy halo, you might instead have seen light refracting through ice crystals in translucent cirrostratus clouds: a warm front was climbing over cold air from behind, pushing higher, cooling and condensing. “It’s going to rain,” my girlfriend said, and that was true. All night and the next morning was a wet mess.

1.

Nick was the first person I told I was leaving my wife. That’s not exactly right. First, I told my girlfriend. Then I told Nick. Then I told my wife. I called him and said we had to go to the desert, and he said okay. On my way to Logan Airport by yellow cab, I saw a coyote standing in the middle of an empty soccer field, looking glum.

I transferred at Denver and flew over the Rockies, headed for McCarran International. The three girls in their gray hooded college sweatshirts seated behind me were smashing back drinks and couldn’t seem to decide whether they wanted to hand in all their money at once or lose it bit by bit over the coming week.

“Woo, bitches,” one of them said, and another said, “Woo.”

A long silence and the turning of magazine pages. Then: “Vegas, bitches.”

One of the girls said, “What if we start with a shot of our feet? And you say, ‘Woo.’ Then the camera pulls out and I say, ‘Bitches.’”

“Girl, you swear too much.”

“Nay, bitches.”

“Girl, that’s just what I mean.”

“‘Bitches’ isn’t swearing. ‘Bitches’ is just bitches.”

“Ladies and gentlemen,” the intercom said, “the pilot has illuminated the ‘fasten your seatbelts’ sign.”

“Woo, bitches,” one of the girls said.

Nick and I rented a car and got out of Vegas. I stared through the window of our Ford Focus at that huge expanse of red rock. In Utah, everything’s hundreds of miles away and you have to drive forever, getting it on, you know, really doing it, motorvating, pedal to the metal, hell-bent for leather, before you get nowhere. The country’s so good to look at that when night falls, it’s a relief. It’s so beautiful it hurts to see.

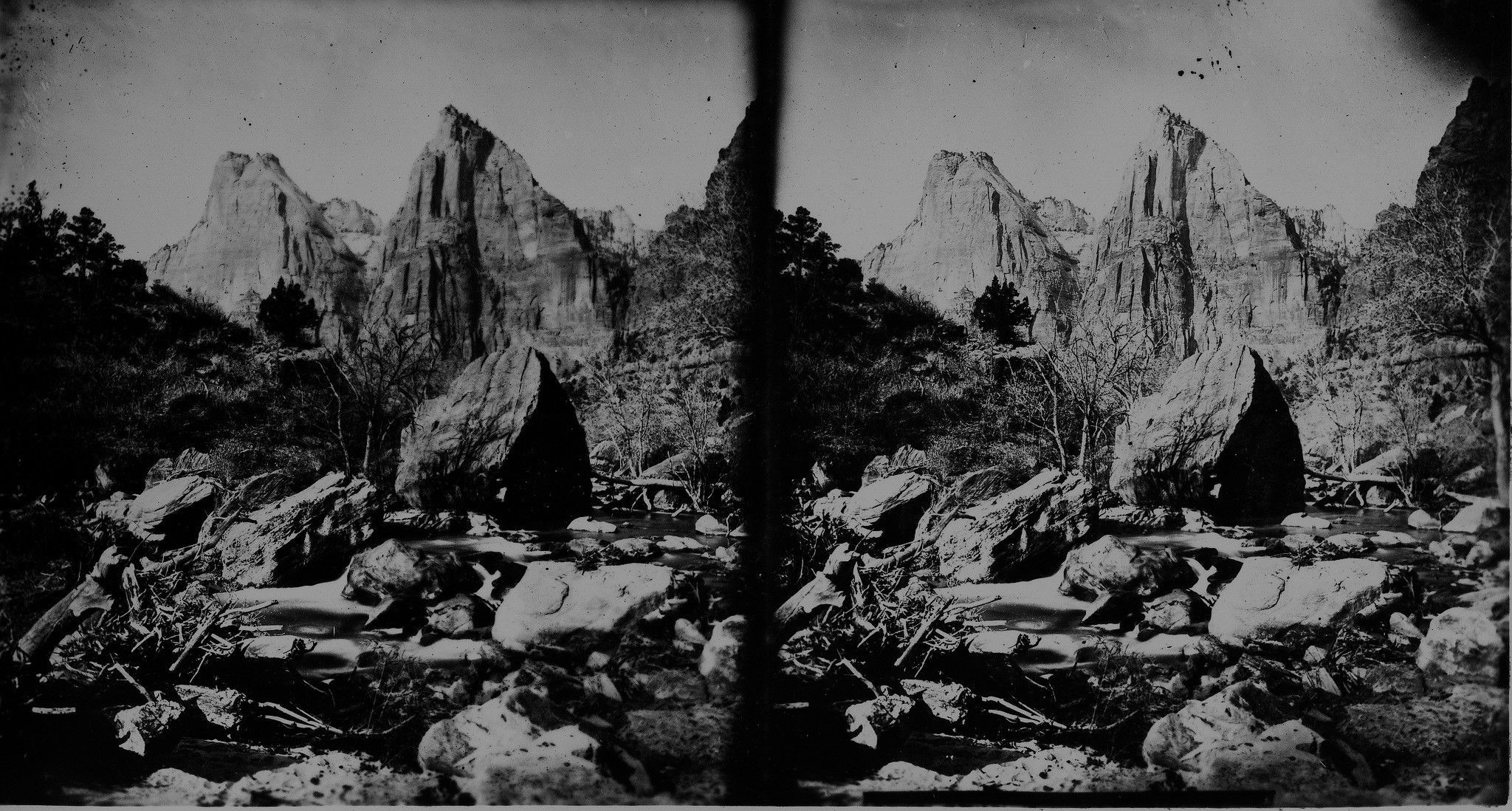

We drove through a dark tunnel more than a mile long under a red mountain. It was not a geological feature and not a feat of engineering, it was something a man might dream. We came out of that tunnel into brilliant sunshine in Zion, Utah. White-tailed deer, jackrabbits, a vole scuttling, come in under the shadow of this red rock. We checked in at the ranger station. They expected an inch or two of precipitation overnight, they said. We got our back-country passes. We parked at the trailhead and changed into our snowpants and boots. We strapped on our packs and hiked miles and miles in, post-holing through the occasional field of hip-deep snow.

I had never seen so many different kinds of country in one day. Ankle-deep, boot-sucking mud. Sand. Scat with hair in it, remnants shat out by some meat-shitting meat-eater. Green trees ringed with fallen blue berries. More trees, burnt twisted and black. Trees beavers had gnawed to points on either end, and the creek they’d dammed.

And all around us in the ravines were sky-high canyon walls; and all around us when we were up on the spines, high on the ridges, were blue vistas so far-ranging they made me sweat.

We made our camp. I zipped myself into a graded-for-below-freezing sleeping bag still wearing my long underwear, silks top and bottom, a T-shirt, three long-sleeved shirts, a fleece vest, a down jacket, a waterproof rust-orange windbreaker, another pair of long underwear bottoms with red-and-brown woodpecker stripes, wool socks, a pair of gloves, and a black balaclava. I wanted to stay warm.

Night fell and with it rain came, swelling the nearby creek. The tent leaked and our boots, sitting outside the tent, filled with water, and the trail flooded as the rain turned to sleet before the sleet turned to snow, obliterating our flooded-out trail. We woke in the dark under three feet of snow with snow still falling.

We rummaged in one of the packs for a roll of toilet paper and we squatted and grunted in the snow, in the dark. Every minute the snow got deeper and the trail, by now nothing more than a suggestion in the snow, became still fainter, more and more obscure. “Hmm,” Nick said. Then he said, “Fuck.”

Our leisurely three-and-a-half-hour hike in became an eight-hour march out through still deepening snow, checking the compass, looking at the bottoms of our boots to see if we had stepped in the red dirt of the trail under all that snow, cutting trail where we couldn’t find the trail, bushwhacking, sloshing through creeks waist-deep where crossing on the smooth rocks was foolhardy because if we had to sleep in the goddamn park another goddamn night we would only be hungry, angry, and uncomfortable, whereas if our sleeping bags got wet we would freeze to death, getting lost and turning back around, pushing snow, staying warm because hiking was hard enough work to make us sweat through our coats.

We didn’t talk much. Once, looking at geologic eons in a striated red rock wall, Nick said, “Lately the forms of things appear to me with time one of their visible dimensions.” It’s Robinson Jeffers.

God, I said to God, when I get back to Massachusetts, if I ever do, I will never complain about shoveling snow again. Instead, I will say these words: I have been to the snow-making factory, where they make the snow, and I took the tour. I mumbled this prayer, or bargain.

“What are you saying?” Nick said.

“In my mind I am drafting a letter of commendation,” I said, “about how your competence and tenacity got us out of this canyon.”

“Not yet,” Nick said. Then he fell.

He slid only about 10 feet, but hit his knee on a rock. I can’t carry him out of here, I thought. I guess I can if I have to. I waited, but he didn’t move.

I said, “Are you hurt?”

“That hurt,” he said, “but I’m not hurt.”

I made my way down to him. “Can you walk?” I said.

He stood up. “We’ll find out,” he said.

About the time we’d had enough, only halfway out of the canyon but already running on fumes, Nick and I ran into five shivering college kids from Michigan. Real kids, young enough to be our sons, if the pregnancy scare Erica and I’d had in 1992 had been even scarier. They had packed in two tents, a pair of snowshoes, an acoustic guitar, a bag of sandwiches, and a gallon of vodka. They knew we’d gone farther into the back country than they had, they’d seen us on our way in the day before and they had waited for us to pass their campsite and cut a trail for them to follow. They were hungover, lost and helpless, abashed. Now we had something to pity other than our dumb selves.

One of them, gap-toothed and sandy blond, drew near me to indicate that he understood the gravity of his predicament.

“Bit off more than we could chew,” he said. “Thank God for you guys. Where you from?”

“Kentucky. Then Boston.”

“I’m from Grand Rapids, if you know it.”

“My wife was from Grand Rapids,” I said.

He didn’t have anything to say about that. “You hike this canyon before?” he said.

“No.”

“Me neither. Mother Zion is angry with us.”

I can’t tolerate that crap, Mother This and Mother That. We kept walking.

“Yeah,” he said, trying again. “First time.”

“It could cure you,” I said.

When they spotted their van at last, on the trailhead across the final decline and grueling ascent, one of the kids threw his hands up and yelled, “Spring Break!”

“Woo, bitches,” I said to Nick.

After nine hours of it we were back in the Ford, slopping red mud in its floorboards, shouting along with Joe Cocker hollering Ain’t it high time we went? and quietly agreeing as Roy Orbison confessed She’s a mystery to me. We stopped for gas and ate tacos and steaks and enchiladas and coffee. We didn’t have a lot to say to each other.

In our motel in Flagstaff, below the snow-line, we ordered General Tso’s chicken and hot and sour soup and fried rice and Mongolian beef and Crab Rangoon. I got up in the night to piss and, forgetting that I couldn’t walk, stumbled and fell into the television. There’s some folks who will tell you that I am still in that motel room, holding my head, sitting on the carpeted floor.

2.

Years later, when, over the winter of 2014–’15, Boston had more than 100 inches of snow, breaking the all-time record, I cheered for more. We’re so close to the record, come on, let’s get it on. We got five feet of snow in February alone.

It became normal to be notified that 20 inches were expected over night. “Today’s headlines: panic and buy shit,” I said to Marc, the owner of the corner grocery, and he smirked. He was making a lot of money. Panic is big business.

A crippling and possibly historic blizzard, the language of advertising. “It’s the crippler!” James said, and we laughed, recalling what Russell used to say about getting with girls back in school. I slipped her the crippler, he said.

But the truth is I was nervous. Three feet of snow, power outages, I’d bought a snow-throwing machine and my neighbors were counting on me. I had started snorting benzodiazepines when I thought no one was looking. They were looking, though.

Our hot water shut down. The furnace began to leak. I was shoveling for an hour, then reading Grammar of Akkadian for an hour: I’d been given permission to audit the course. I shoveled, then I listened to Sonny Criss’s “The Black Apostles” before I shoveled some more. I did two shifts with the snow-thrower and snorted half a pill I chopped up with the edge of a nail-file, I thought I was so smart. I flagged a city plow down out on the main drag and paid him cash to come down our dead-end street. He pushed the snow high enough to block my neighbor David’s kitchen window.

Another foot of snow. I cleared the window-well, the furnace vent, and the gas meter. I shoveled the stairs to the basement: without enough clearance over my head to pitch the snow out of the well, I had to fill and refill a plastic bin and haul it up the stairs and dump it out back. I cleared both downspouts. I chipped off the undercarriage-scraping ice-block that had formed at the mouth of our street: while I did that, a man walked out in his robe and house-shoes to stare at his Honda Civic: plowed in along the main drag, now frozen solid under feet of dirty ice.

Another foot of snow. Concerned about flooding when and if the melt began, I shoveled the storm drain clean: used the long-handled ice-chipper until I could see iron and concrete, then worked on my hands and knees with a paint-scraper, getting lost in the details until it was one hundred percent ice-free, and finally heated kettle after kettle on the stove-top and poured two gallons of scalding water over and into the grate.

Another foot of snow. Night after freezing night, I dreamt of Death Valley, where in 1913 this temperature had been recorded: 134 degrees Fahrenheit, in the shade. Death Valley is full of flowers, my dream said.

At night, I stood on the brick terrace in the dark, in the deep snow. I wasn’t in danger; I could call for help, and friends would come running: I was close enough to see the lights of Erik and Traci’s house, and Arthur and Jane’s house, and David and Judy’s house, and Bill’s house, and Brenda’s house.

But I looked at the stars, remembering Zion, and I trembled.

¤

LARB Contributor

J.D. Daniels is the winner of a 2016 Whiting Award and The Paris Review’s 2013 Terry Southern Prize. The Correspondence (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) was published in 2017. His writing has appeared in Esquire, The Paris Review, n+1, Oxford American, The Los Angeles Review of Books and elsewhere, including The Best American Essays and The Best American Travel Writing.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!