Dancing in Beijing: Lisa Brackmann on Gail Pellett’s “Forbidden Fruit”

Gail Pellett making bad choices in 1980s Beijing.

By Lisa BrackmannJuly 5, 2016

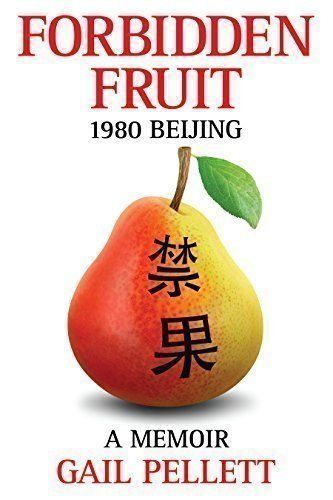

Forbidden Fruit — 1980 Beijing by Gail Pellett. VanDam Publishing. 400 pages.

READING GAIL PELLETT’S MEMOIR of 1980 Beijing, Forbidden Fruit, was like a trip down a memory lane I’d half forgotten. I spent six months in China, mostly in Beijing, in 1979 and 1980, leaving shortly before Pellett arrived. My experiences in some ways were very different from hers. Pellett was 37 years old, a journalist who’d worked in a variety of settings and an activist well versed in leftist and feminist discourse and movements of the ’60s and ’70s. I was a student barely out of my teens who hadn’t decided on a major, much less a career, and while I had some notion of politics, I’d had nothing remotely close to her immersion or commitment. Her job situation, working as a “Foreign Expert” at Radio Beijing (China’s Voice of America), was higher profile and undoubtedly more politically sensitive than mine — I was a “Junior Foreign Expert” teaching English Conversation to college kids older than I was at a “branch school” of a large university, roughly equivalent to a community college. The students were older because many of them had been “sent down” to the countryside to absorb peasant wisdom during the Cultural Revolution, and the schools had only just reopened.

But there are certain things about that particular time in Beijing that were universal for most foreigners living there.

Pellett writes about the isolation. The surveillance. The constant struggle to do anything independently, without minders — in her words, of living “in a completely mediated world.” The near impossibility of having normal relationships with Chinese people. The willingness tinged with desperation of Chinese people to ask us foreigners for favors, thinking we had some magical guanxi that could get them into grad schools, or at least into the Friendship Store for some cooking oil. The whipsaw changes in policy that made it okay one day to have Chinese people gather at your apartment and dangerous or forbidden the next. The strange privilege that came with being a Western foreigner, something that was used to further isolate us, and the resentment that it created among our hosts.

And the constant requests to “demonstrate the disco dance.”

That last one happened to me more times than I can count, and I was far from a model representative — I didn’t even like disco dancing.

Adding to the weirdness of this whole disco obsession was that, like the policies on fraternizing, the politics of dancing were extremely fraught. At the end of our teaching term, we’d planned to have a big party with our students. The school officials canceled it at the last minute. They were afraid that dancing might occur.

If dancing with foreigners was problematic, you can guess how having sex with foreigners was regarded.

I knew foreigners who’d had relationships with Chinese people. One American woman I knew was dating a famous accordion player. Yes, that was a thing in China at the time. He was the equivalent of a rock star. I met him at a drunken Christmas party at a Chilean embassy official’s apartment. I even knew a gay teacher who’d had a lengthy affair with a Chinese man. But this was serious stuff back then and could be very risky for the Chinese partner.

I had a student in one of my classes, a very pretty woman whose hair was styled more than my other female students, her eyebrows shaped and her lips slightly reddened. She was quiet, with a small, perpetual smile, like she had some secret source of amusement. One day toward the end of the term, several officials pulled her out of class. I never saw her again. I was told later that she’d been seen “riding in cars with foreigners, and she was not wearing a hat,” the implication being that she was engaging in prostitution (or just that it looked bad), and that she’d been sent to a reform camp.

¤

Despite all this, Pellett embarked on a series of sexual adventures with Chinese men. These ranged from a brief affair with an inexperienced young grad student whose term of endearment for her was “My Chairman,” to an encounter with a sexy folksinger, to a longer relationship with a man named Fan that might have had the potential for something more but was never allowed to fully develop.

Predictably, all of these connections were quashed by various authorities.

Pellett finds herself blocked from making any meaningful contributions at Radio Beijing, constantly thwarted from forming any meaningful relationships with Chinese people, and disillusioned by the failings of Maoism and collectivism. She eats too much, drinks too much, plays soul music at earsplitting volume and dances in her apartment, takes midnight bike rides around Beijing in defiance of her minder’s warnings — anything to bring some kind of life and color and sensual pleasure into a drab gray city where joy seems as rationed as cotton or cooking oil, inhabited by a population traumatized by the Cultural Revolution and decades of Maoist mood swings. The people working alongside you could have been tormenters or victims or both. Students had tortured teachers, family members had denounced and betrayed each other, workplaces had a times degenerated into violent anarchy, and all that chaos had ended only four years before. Basic bonds of trust between people were frayed and broken, with petty and arbitrary authority often providing the available social glue.

Pellett found Beijing’s foreign community mired in the same kind of double-edged privilege, surveillance, and hopelessness she encountered. She met journalists who were also intelligence assets, impoverished African diplomats, political dissidents with no official status and no country to go home to, old leftists who had taken sides in factional conflicts that they’d both won and lost. Eventually, Pellett writes:

My identity was shriveling. Creative work had always occupied a huge place in my sense of self. Along with the deep satisfaction from my work I had sometimes managed a love relationship. Both were absent here. Forget love.

When her bosses at Radio Beijing and other unnamed “top leaders” forced an end to her relationship with Fan, Pellett resigned her position less than a year into her two-year contract and returned to San Francisco.

As a memoir, Forbidden Fruit has its flaws. Pellett’s attempts to relate her experiences in Beijing to her experiences in childhood and as a young adult often feel disconnected from the main narrative. You may find some of Pellett’s behavior frustrating as well. There were times when I wanted to reach into the pages and back in time and yell, “What were you thinking?!” Beijing in 1980 was just not the place to try and work out your relationship issues, especially when doing so could cause so much trouble for your Chinese partner. On the other hand, the men in Pellett’s case were willing partners, often initiators. And thinking back to my time there, I had my own moments of stupidity and overwhelming frustration, moments when I acted out like a teenager in the middle of a tantrum. How can I blame another flawed human being for reacting in a human way when almost all normal outlets for satisfaction and joy were forbidden?

Taken as a whole, Forbidden Fruit captures a specific, peculiar moment in time and place, what it was like to be a foreigner in Beijing at the beginning of Deng’s reform era, as well or better than any book I’ve read. Forbidden Fruit reminded me, too, that in spite of the obstacles, it was possible at times to connect.

Once, we were able to hold a Christmas party for a group of Chinese students from the main university where my friend’s parents taught. We had a proto-boom box, a huge monstrosity that weighed a ton and put out a lot of sound. And we had all kinds of tapes of the latest music from the States: Talking Heads, the Clash, Bowie, the Sex Pistols, along with oldies like the Beatles and the Stones — and, of course, some disco favorites. I will always remember the scene: the lights in the Friendship Hotel apartment turned down low, the music blasting, the students moving their feet and their hips, some jumping up and down, lifting and waving their arms wildly, their smiles and their laughter.

Dancing had taken place, and so had joy.

¤

LARB Contributor

Lisa Brackmann is the critically acclaimed New York Times best-selling author of the Ellie McEnroe novels set in China. The latest, Dragon Day, was a Seattle Times Top 10 Mystery of 2015 and is short-listed for a Lefty Award. Her most recent novel is Go-Between. Her work has also appeared in The Wall Street Journal, Travel + Leisure, and CNET. She lives in San Diego with a couple of cats, far too many books, and a bass ukulele. You can find her online at lisabrackmann.com.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Things That Make Me Angry

Kim Fay talks to Lisa Brackmann about broaching tough subjects in her crime fiction while also staying funny.

Ardor and Tenderness in China’s Capital

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!