Crisis Industry: On Simon Hanselmann’s Pandemic Webcomic

What a graphic novel about disaffected stoner monsters reveals about the political and economic crises of the pandemic.

By Jack ChelgrenOctober 4, 2021

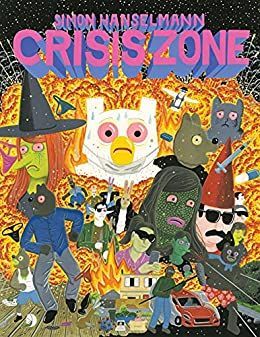

Crisis Zone by Simon Hanselmann. Fantagraphics. 292 pages.

IN SIMON HANSELMANN’S Megg, Mogg, & Owl comics, it always feels like the world is ending — in the most pathetic and zonked-out way imaginable. The series, which got popular as a webcomic on Vice in the early 2010s and now spans eight books and numerous zines, follows the lives of three stoner monsters: a witch named Megg, her cat boyfriend Mogg, and their uptight housemate Owl (who is, indeed, an owl). Alongside half a dozen or so Halloweeny companions, Megg, Mogg, and Owl grapple with bad jobs, bad drugs, bad relationships, bad mental health, and other vicissitudes of being 21st-century dirtbags.

It’s odd but strangely comforting entertainment, like BoJack Horseman gone off antidepressants and transplanted to Seattle. In the guise of a stoner comedy, the stories plunge headfirst into the modern malady Lauren Berlant called “crisis ordinariness,” the kind of life where surviving means, at best, “making a less bad experience,” and at worst a kind of “slow death.” [1] Limned in bilious, bloodshot watercolors, these monsters subsist in an ambient disaster. They’re not always in mortal peril, but nothing about their lives feels sustainable.

With the latest installment, the crisis gets less ordinary and even more intense. In March 2020, as the world lurched into lockdown, Hanselmann began serializing new Megg, Mogg, & Owl material on his Instagram, a story line set during the pandemic. He posted 10 panels a day nearly every day for nine months, trading his usual watercolors for a starker palette of ink and colored pencil, and following his characters as they struggled to cope with the same upheavals as readers. By the time he uploaded the final sequence in December, the project, aptly titled Crisis Zone, had garnered a large online following and grown into the most expansive narrative in the series by far. A print book version, with additional panels and a snarky afterword, was released by Fantagraphics this past August.

Reading Crisis Zone feels like watching a supercut of someone doomscrolling from March to December of last year. The book trawls through the wreckage of 2020, documenting its panics, obsessions, and micro-trends, and careening down cultural rabbit holes. It’s a harrowing trip, as Hanselmann sometimes lapses from clever satire into trollish provocation. But ultimately, Crisis Zone is a sensitive, sometimes funny, sometimes disturbing account of last year: a story about what it’s like to have terrible friends during a pandemic, and a reflection on how economic and political hopelessness collided to make that situation even worse.

At the beginning of lockdown, Megg, Mogg, and Owl’s house is overrun by a small army of friends fleeing rent and bad roommates. These are Hanselmann regulars, among them the amoral party fiend Werewolf Jones; Jones’s diabolical kids Diesel and Jaxon; and Booger, a trans boogeywoman who is also Megg’s off-and-on paramour. Things fall apart almost instantly. Owl and Jones lose their jobs, the weed supply dwindles, everybody gets COVID-19, and before long the friends are swept up in a chain of debacles that makes the previous books’ fiascos feel quaint.

Not least among the new challenges is a fundamental disruption of the friends’ slacker lifestyle. Deprived of old sources of income and other support systems, Megg, Mogg, and Owl find they must scramble to make ends meet. Accordingly, work, the awfulness of work, and the struggle to find work feature more prominently in Crisis Zone than in any previous Megg, Mogg, & Owl story. A good part of the plot revolves around a single very bad job. About halfway through the book, Werewolf Jones goes viral on TikTok for the extreme dildo porn he’s been filming in the living room. His sudden fame leads to a TV deal with Netflix for a Tiger King–style reality show called Anus King, wherein he, Owl, and the rest of their pandemic pod find themselves the stars of a fraught pop culture spectacle.

Jones isn’t the only one who gets a new gig. As the story unfolds, Mogg temps in an Amazon warehouse; Jaxon and Diesel open a scummy hotel in a treehouse; Owl and Booger make OnlyFans accounts; and Jaxon scrubs toilets at McDonald’s. Hanselmann’s choice of these jobs in particular — jobs that epitomize certain highly contemporary forms of work like service work, gig work, online sex work, and e-commerce logistics — bespeaks an ambition to think structurally about the state of labor in the present. These aren’t just jobs; they’re allegories. Crucially, though, these jobs aren’t too different from the work everyone did (or didn’t do) in previous books. Jones was already making porn in Megg & Mogg in Amsterdam (2016). Megg has been on unemployment since the very first collection, Megahex (2014). And for the entirety of the series, Owl has shuffled between what David Graeber memorably termed “bullshit jobs.” [2] These narrative continuities with the pre-pandemic world affirm that work was getting worse long before 2020 — COVID-19 just hurried things along.

Thus, Crisis Zone winds up doing something like political economy for work-averse stoner monsters. Its survey of precarious employment aligns with economist Aaron Benanav’s argument that a key expression of capitalist crisis today is not mass unemployment but mass underemployment. [3] To Benanav’s analysis, Hanselmann adds that the underemployed hedonistic slacker might be a natural avatar of a global economy that’s been stagnating for decades. Certainly, in a world where options for those without inherited wealth are increasingly limited to either landing a job in the latest booming industry or cobbling together an array of underpaid positions, the portrayal of arduous work in Crisis Zone feels distressingly familiar.

But even as Crisis Zone clarifies some macroeconomic causes of its characters’ misery, Hanselmann heads off any impulse to find these monsters relatable. In fact, he goes out of his way to make them detestable, notably by playing up their contempt for politics. This is no different from the rest of the series — Megg, Mogg, and Owl have always been allergic to social justice lingo, activism, and the like. Still, this aspect of Crisis Zone could come as a surprise to uninitiated readers. After all, the book’s queer, anti-work, generally nonnormative subject matter might seem to make it ripe for gritty explorations of progressive themes, as one finds in other recent indie comics like Ezra Claytan Daniels and Ben Passmore’s BTTM FDRS (2019) and Michael DeForge’s Heaven No Hell (2021). But Hanselmann’s crew is resolutely disaffected. Instead of righteous indignation, they’re more apt to ooze cynicism; instead of class consciousness, they cultivate drugged-out unconsciousness; and instead of radical queer community, they scrape by in radical queer dysfunction.

The turmoil of 2020 only exacerbates this nihilism. Throughout Crisis Zone, Megg, Mogg, and Owl spend far more time fretting about cancel culture than they do considering why riots are happening all around them. The George Floyd rebellion stays mostly in the margins, surfacing occasionally in the omnipresent ACAB graffiti that looms in the background whenever someone ventures out of the house. Seattle’s monthlong occupation protest, the CHOP, makes an appearance when Megg passes out on a sidewalk and wakes up in a protester’s tent. The camp doesn’t exactly get a good review. “My god,” Megg exclaims, “it’s just politics and activism

everywhere

! It’s like Twitter’s been smeared across every single surface.”

In this instance and others, Hanselmann turns his characters’ anti-political sensibilities toward a compassionate consideration of why someone like Megg might hate politics. Megg is disgusted by the CHOP because (at least in Hanselmann’s rendering) it’s dirty and overrun by white people trying to one-up each other as antiracists. But that’s not all. Megg is alarmed by the fact of the camp itself, the danger, disruptiveness, and instability it represents. If the latter reaction doesn’t style her as particularly noble, it does warrant some degree of empathy. Militancy can be frightening, and here Hanselmann examines the contours of that fear for a depressed witch like Megg, who hates the way the world is but recoils from the messiness of trying to change it. In any case, although Hanselmann refuses to condemn Megg for not rushing to the barricades, he doesn’t suggest that her cynicism is correct or virtuous. Rather, he parodies his character’s self-involved, head-in-the-sand detachment, while thumbing his nose at the type of puritanical leftists who view despair or any criticism of social movements as counterrevolutionary sins.

Still, some of the more extreme displays of bad politics in Crisis Zone lose their satirical edge by replicating the same narrow-mindedness the book seems to want to critique. The most troublesome moment comes at the story’s climax. Werewolf Jones’s Netflix show, Anus King, has spiraled into one catastrophe after another, but no amount of chaos or scandal appears capable of shutting it down. When things finally do reach a breaking point, Jones decides to end Anus King with a PR coup de grâce, the one thing guaranteed to get him canceled for good: he puts on blackface on camera. Like other especially gnarly stretches of Crisis Zone — such as jokes at the expense of #MeToo and a bizarre subplot where one of Jones’s kids comes out as trans and two other trans characters question whether she’s “faking it” — this twist feels engineered to goad readers who might question whether it’s acceptable for Hanselmann to play with such loaded material. Admittedly, there’s more to Jones’s transgression than just shock value. Hanselmann is trying to skewer the hypocrisy of a culture industry that will churn out all sorts of other racist and atrocious material, so long as it sells or increases someone’s clout.

But even so, the satire of this moment misses the mark. By making blackface the pinnacle of the book’s study of political nihilism, Hanselmann signs on to the idea that politics is basically about not offending people. This is the same attitude that leads Megg to despise activists categorically, whether they deserve it or not; the same cynicism that compels the whole friend group to deem pretty much anything with a whiff of the political an obnoxious waste of time. But unlike these other moments, the blackface incident leaves little room for the possibility that politics, done right, might mean fighting to alleviate oppression, not hurt feelings — or that blackface might be harmful for other reasons than bothering people on the internet.

At its best, Crisis Zone points to a problem that last year made frighteningly clear. For many, politics feels futile because it seems to have little or nothing to do with life’s most pressing concerns: how to get through the day, find community, and feel okay with yourself. Hanselmann’s attention to the lamentable state of work in tandem with the lamentable state of politics suggests that we might think of this problem as a gap between the political and the economic, where politics means negotiations of power and economics means the ways people get what they need and want. In this gap, Hanselmann highlights a vicious cycle: politics feels pointless because living in an era of crisis ordinariness is bleak and exhausting, and also because a lot of what passes for politics today really is quite performative and compromised. But as Crisis Zone makes plain, the bankruptcy of politics is self-actualizing. When people despair about the world, their detachment from social problems only makes matters worse, and leads them to misunderstand, fear, and distance themselves from the most urgent struggles of our time.

This book offers little in the way of solutions; redemption isn’t in Hanselmann’s wheelhouse. But if Crisis Zone or any of the Megg, Mogg, & Owl books have a point, it’s that things can be messed up and still worth the trouble. Friends can be cruel, bad jobs can get worse, but there’s a glimmer of okayness in blundering through the wretchedness and finding, if you’re lucky, that you’re not alone. This seems like a good argument for holding fast to the political, for squinting through the fumes of pessimism and depression to light up the fights that could still make our crises more bearable.

¤

Jack Chelgren is a writer from Seattle now living in Chicago.

¤

[1] Lauren Berlant, “Slow Death,” Critical Inquiry, vol. 33, no. 4 (2007), 779.

[2] See David Graeber, Bullshit Jobs: A Theory (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018). Graeber defines “bullshit jobs” as “a form of employment so completely pointless, unnecessary, or pernicious that even the employee cannot justify its existence even though, as part of the conditions of employment, the employee feels obliged to pretend this is not the case.”

[3] Aaron Benanav, Automation and the Future of Work (London: Verso, 2020).

LARB Contributor

Jack Chelgren is a writer from Seattle now living in Chicago. He is a PhD student in English at the University of Chicago and assistant editor at Chicago Review.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Toward a Labor Theory of Generation X

Alissa G. Karl offers a labor theory of Gen X.

Timeline, Flattening: Everyday Life in a Pandemic

Living through a quotidian catastrophe, one desperate text at a time.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!