A Conversation with Richard Blanco: "One Today," One Year Later

Richard Blanco – the first openly gay, the first Latino, and the youngest presidential inauguration poet ever.

By Gregg BarriosJanuary 4, 2014

AN UNEXPECTED CALL in December 2012 changed Richard Blanco’s life: he was asked to write an original poem for President Barack Obama’s second inauguration. For a brief seven minutes in January, he was front and center reciting his poem, “One Today” before a national TV, radio, and online audience of 20 million — and countless more worldwide. Media and poetry critics lauded his poem, placing it among the best inaugural verse. Just as important was the TV image of the handsome, 45-year-old Blanco, the first immigrant, the first Latino, the first openly gay, and the youngest person selected for the honor of inaugural poet.

The White House initially said that he was selected because his “deeply personal poems are rooted in the idea of what it means to be an American.” In a short introduction to the published poem, President Obama writes, “Richard’s writing will be wonderfully fitting for an inaugural that will celebrate the strength of the American people and our nation’s great diversity.”

Blanco’s turn as inaugural poet has led him through a magical year of high visibility — the most celebrated poet in these United States of poetry. His new literary life began with readings at Yale and a conversation with Elizabeth Alexander, Obama’s first inaugural poet. He recited a new poem, “To the Artists Invisible” at the Fragrance Foundation, and then on to a citywide celebration in Miami where he also spoke to Radio Martí and the Voice of America in impeccable Spanish. His reading at the Library of Congress focused on his gay sensibility. At midyear, he opened the Boston concert for the victims of the marathon bombing with a new poem, “Boston Strong.” It struck such an uplifting chord with Bostonians that he was invited to read the poem in Fenway Park before a Boston Red Sox game.

Blanco returned a hometown hero in Bethel, Maine, where he lives with his partner. Still reeling from the literary whirlwind, he remarked that perhaps now he could leave his day job as a professional civil engineer and earn his living as a full-time poet.

Blanco was certainly not a household name prior to his selection. His name will draw a blank until the descriptive “inaugural poet” is added. Even a search through the pages of the august Poetry magazine won’t turn up a match. And yet, Blanco’s three previous prize-winning collections (Directions to the Beach of the Dead, City of a Hundred Fires, and last year’s Looking for The Gulf Motel) speak volumes of who he is and how his poetry speaks to us in a new, unique voice.

I’ve known Blanco for nearly a decade. I first met him at Sandra Cisneros’s Macondo Foundation summer workshops in San Antonio, Texas. On one occasion, he was the facilitator of a poetry workshop. And while most of the poets in the salon were Mexican American, Blanco’s Cuban heritage meshed well.

For some Latinos and gays, Blanco’s inaugural poem left something to be desired, both in terms of cultural and social history. Others felt the president upstaged Blanco by speaking on LGBT civil rights at Stonewall and on the immigration issue, topics that are important in Blanco’s life and to his poetry.

In the first part of our “plática,” we discussed his first forays into poetry as a child in Miami; his first collections; and how his gay self finally emerged in Searching for The Gulf Motel. In the second part, I learned that Blanco had written two other poems for the White House Inauguration Committee. He discussed how he wrote these three poems for the inauguration and shared the reasons why the other two were not selected. He also shared his plan to put poetry back into the schools and in our daily lives.

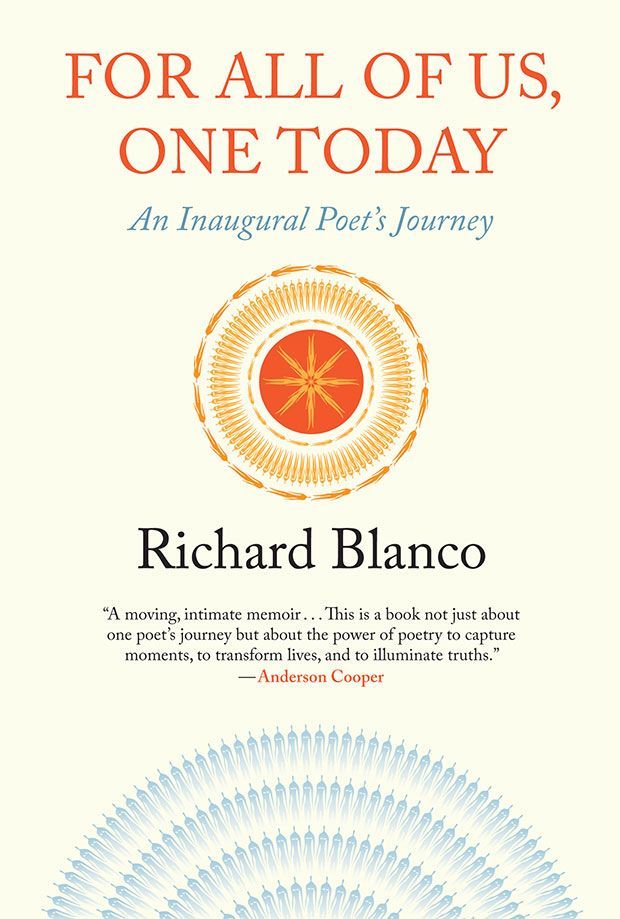

I initially spoke with and emailed Blanco last January, but the White House had embargoed all media interviews except for The New York Times and NPR. We reconnected on the eve of the publication of his new memoir, For All of Us, One Today: An Inaugural Poet’s Journey.

Blanco apologized for making the wait so long. Our conversation took place by phone. He spoke from his home in Bethel, Maine. We spoke in two separate and lengthy sessions. At the end of the first session, he joked. “Once you get a Cuban talking, he never stops.”

— Gregg Barrios

¤

Gregg Barrios: You open the memoir “For All of Us, One Today” with a recollection from school:

Days before our field trip to the science center, Mrs. Bermudez tells our class the sun is actually hundreds of times larger than the earth. […] I don’t want to believe her; the sun is the size of a sunflower, I insist. I draw lemon-yellow petals around it and color its center sienna brown.

Was that incident an early manifestation of an artistic streak?

Richard Blanco: I was one of those right-brained, left-brained kids. Later as an adolescent in high school, I had the same standardized test scores in verbal and analytical. I’d draw a sunflower and then the floor plan for a house. There was always a creative side and a very analytical side. Of course, much of the creative side was not fostered given our circumstances. We were a working-class family, and of course my grandmother’s homophobia — all these factored into my making a career choice at first with engineering.

Certainly, I was always coloring or doodling, or doing something with plaster of Paris, with anything creative, but I was also good at math, life sciences, and that particular moment you’re speaking of, I’m not sure if all of us can go back to that moment in our lives, but certainly, it’s like a glimpse of your mortality. You realize your world is so much bigger than you thought it was, and that you are not the center of it and neither are your family or neighbors. So yes, I’ve always had that creative streak that eventually surfaced in writing.

There is also the implication that you are going to do it your way.

I remember even in physics classes in college, I would do problems a different way and get at the right answer — so why can’t I do it that way? I guess it’s the creative spirit, and you’re somewhat defiant — choose what you believe and choose how you see the world and record it as you see it.

That kid making his own sun would one day open his inaugural poem with the line, “One sun rose on us today […].”

It could well be. You know how art just happens. When I started writing the memoir, that was the first image that came into my head. It’s that moment when you realize the earth is not the center of the universe and neither are you, but there was a subconscious connection there.

Everything in art is connected. Every single moment is the past, the present, and the future. And the actual sun in the poem is connected to rural Maine and the small town Bethel where I live as I watch the sun rise over the pines. It was this moment of illumination — the transcendent power of nature. The poem took off from that one line. But now you’re making me think that it is connected to the idea from way back. It was something very important in my life and in my soul. It’s funny how those moments stay with you and keep surfacing in your life.

José Martí’s poem “Guantanamera,” later set to song, is ever-present in your poetry. “Mi verso es un verde claro, y de un carmin encendido.” That is a very powerful image of color in nature and verse. Is that a very Cuban thing?

The “Guantanamera” reference is to the unofficial national anthem of Cuba. Every Cuban knows it by memory. It’s part of the folklore you grow up in. It does everything a poem can do. It is Cuba before Castro, during and even now in Communist Cuba, it lives on. I remember the exile community singing it with tears in their eyes. Even though I was too young to understand the details and nuances, you still feel this incredible sense of loss and pain and longing. It is engraved in my culture. You have to sing “Guantanamera” to keep your Cuban life.

As far as the colors, I’m a very imagistic writer. I tried painting for a while, and now that I am confessing a lot more, I’m always cognizant of symmetry and colors. I always try to find the right color for something I’m describing, more so than smells or sound. And going back to the inaugural poem, there is a line that everyone quotes, “the plum blush of dusk.” Again, it is the incredible colors of each, individual dusk. I don’t know, Gregg, but you’re really getting me to think how prevalent colors play in my work.

William Carlos Williams and Wallace Stevens have influenced your work. There is a great use of colors in your poems — “Postcard to W. C. Williams from Cienfuegos” and “Tía Olivia Serves Wallace Stevens a Cuban Egg.”

Are you sure, you’re not a therapist? I think this is really cool. My first moment in poetry was seeing a red wheelbarrow and reading Williams’s poem and watching my mother cooking. It was when I first realized what poetry was. The heavens parted and this is poetry! I’ve always written from that moment onward with the idea of capturing that thing. It was more of seeing and getting that image precisely right.

There was another connection I had to both writers — that both of them had other careers — completely different livelihoods. Which has always fascinated me. Another level — they have that other side to them. I carried them not only as models for writing, but for pathways or journeys, for what a poet can be or do in this world. Williams is my right brain and Stevens is my left brain. They are impenetrable — like Stevens’s “The Idea of Order at Key West,” I’m just fascinated by that poem, and every time I read it, I think of something different. So they [Williams and Stevens] are like two ends of the spectrum for me. I think of Stevens as more than an idea person, and how he works his poems — he uses constructs like an engineer, and he likes to build things piece by piece. And you look at it, and you can’t peel it apart, it’s as solid as a building or a bridge.

In my Stevens poem, “Tía Olivia,” I was playing with the color of the egg yolk. I was having fun with him; I could see myself in him: “What is this yellow? I really have to know what exactly it is.”

It is a fun poem. The ending is just delightful.

If you met my Tía Olivia, you would see they were entirely different personalities.

Williams was part Latino.

Right. When I saw that his middle name was Carlos, I was immediately attracted since my father, brother, and grandfather’s name is Carlos too.

I’m moved by your recounting your family history, exile, and diaspora. Each revelation is not unlike adding new verses to “Guantanamera” or “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” with more urgency, detail, and understanding. Is your intent to enrich this history not only chronologically but also spiritually and culturally?

Oh yeah, it certainly interests me because what I think has happened is that you ask a question once, you ask it twice and three times — the memory of all the exiles, and the family members — but with each book, time moves forward. New revelations happen or new facets are happening. For me in particular, I’ve seen my mother from book one to now as she has overcome all that longing, suffering, and loss. She has come to a place in her life that’s triumphant.

It’s a never-ending story. Sometimes when I finish a book, I say I’ll never write about this Cuban stuff again, right? And then I’ll have a flashback or visit an old aunt or relative for the last time, and want to honor their lives and dignity, and honor how they were able, despite all their losses, to stand on their feet and die proudly as full human beings. The story keeps on growing. It’s my own sense of diaspora, and how I’ve felt more comfortable in my life inheriting that sense of the exile that I’m going to be home sometime — home, home, where is it? As I say in the memoir, I’ve been home all along. As their story evolves, my story keeps evolving too. It becomes my own trajectory, my own moment, and my own timeline. That’s what was different about Looking for The Gulf Motel. It turned a corner. Went other places. It went to Maine. It spoke about my sexuality.

In “Since Unfinished,” the final poem in Gulf Motel, you pay homage to Whitman, your other poetic grandfather after Martí, with a nod to Leaves of Grass when your actual grandfather shows you how to make a leaf of grass sing. I had goose bumps.

It comes from an adage of a famous poet, of writing the same poem all our lives — not literally but metaphorically. And that struck me. There is really no beginning and no end. We are witness to what we see, what we record, what we do, and what happens around us. Life isn’t a linear progression; it’s a loop. We go over the same things, but as we move forward, it’s still a loop. For me, the last poem I write before I turn in a manuscript to the editor is always the beginning of the next one.

Growing up, did you speak Spanish at home?

When I was two or three years old my parents would ask me: how do you say this in English? My brother was six and a half years older so he had a harder time learning English. So I was the official translator for them for three or four years. I learned English at daycare. My parents never spoke English at home — only a word here or there — una palabrita. They knew when we said a bad word, but they had a working knowledge of English to get by in their jobs in Miami — of course you don’t have to know that much English in Miami. But they never spoke English to us. Later on when we were teenagers, we would speak to them in English, and they would understand us. There was a weird symbiotic relationship, because they liked to hear English so their own English would improve. That’s how I grew up.

Outside the home, it was predominantly English. But growing up in Miami, the whole community was Cuban or Cuban American. Ninety percent of my classmates were bilingual. There was this tower of language that you would instantly hear. The things we Cuban-American kids got away with from the nuns who didn’t speak Spanish, but you know how that works because you went to parochial school too. The same things happened with my parents when my brother and I wanted to talk about them, or were plotting to see what we could get away with. So I grew up in a Spanish-speaking household, I don’t ever remember not knowing two languages, which is really odd to me.

Those images of American TV shows keep repeating themselves in your poetry — especially in the poem “América” — one of your finest poems. Did you want to identify more with those TV shows than the young Cuban boy?

Oh, certainly. I don’t know how it was for you, and I’m not interviewing you, nor do I speak for all Latinos. But the butcher was Cuban, the mayor was Cuban, and the plumber was Cuban. I was living in a cultural bubble. As I always like to joke — Miami was like a cultural purgatory between the real America and the real Cuba my parents talked about.

I really believed that the America I saw on TV was really out there because it certainly wasn’t in my neighborhood. I didn’t know any better. There was also a generational issue. Anything your parents liked, it was a meeting ground for rejection. You love it, but you hate it, and try to negotiate where you belong between those extremes. Either I wanted to go to Cuba and be Cuban or I wanted to be American because later in adolescence, you view your parents as tacky. “I’m not Cuban, I’m American. I want to be as American as apple pie.”

They would embarrass us because they didn’t know English. One of the threads in all my poems is falling in love with your culture. You hit the age of 23 or 24, and you ask the big question: where the hell am I from? All along you thought you were rejecting it, but it was ingrained in your soul. Then you start understanding this sense of place and identity — which is still a real question for me in many ways.

Living in Maine, I’m like, am I Cuban anymore? I’m never going to be Cuban the way my parents were Cuban. There is a certain amount of rejection, but it was a knee-jerk reaction. The story your parents told you about Cuba, how wonderful, blah blah blah. The beach was better in Cuba, the mangos were better in Cuba, and the sugar was sweeter. Then as an adult I realize this has always been part of my story.

I’m still addicted to those TV shows. I’m still in love with my fictional America, the same way I’m in love with the fictional Cuba that my parents spoke about. I like that. It’s an intangible, which is always what you are trying to reach for in art and poetry.

James Joyce wrote, “What’s in a name? That is what we ask ourselves in childhood when we write the name that we are told is ours.” Why Richard instead of Ricardo?

I love that quote — that’s exactly right. I never liked Ricardo in English, it never sounded right to me. I had another identity in English — another culture. I went through the whole process. Whenever I’m asked for middle initial, what do I put? It has always been a source of whimsy in my life, a focal point. The name has so much to do with how you see yourself. When I renamed myself Richard, it was because I wanted to cross over into that other world. It ended up being my pen name, but my legal name is Ricardo de Jesús Valdés Blanco. When I look back I think maybe my pen name should have been Jesus White. But really your name is how you see yourself. It was also the way it sounded. I was someone else in English, and in Spanish I was Ricardo — “Ricardito.”

You grew up in a very homophobic era and environment. Considering how your grandmother and others were trying to show you how to be a man, how early did you know that you were gay?

Probably when I was five. Let me think back. Whenever the The Six Million Dollar Man came on TV. That was my first love. I was so in love. I didn’t even know what gay was. I was too young to understand the concept of sexuality. But I was incredibly attracted to Lee Majors — certainly at a very young age. Once my grandmother came into the picture, it really became a sticking point. I think I knew, I always knew.

I led a straight life. I came out when I was about 25. And I won’t lie either, I think I could have been one of those people that led a straight life, got married and had kids — and done it the old-fashioned way and eventually had illicit affairs with men or whatnot. I had a girlfriend at the time, and I really loved her. It was heading toward marriage. I finally had the courage to say I can’t do this to someone I really loved. I eventually made the choice that I didn’t want to live a lie.

In “Abuela’s Voices: A Chronicle,” and in “Queer Theory According to My Grandmother,” you quote your abuela as saying, “I’d rather have a granddaughter who’s a whore than a grandson who is a faggot like you.” How did you negotiate such traumatizing words and forgive that person who supposedly loves you?

Only after much therapy. When you’re a kid, you love her unconditionally, and you want to be loved, and at the time, you are just trying to please your grandmother. You act like she tells you not to act. What essentially made sense to me was that my grandmother ultimately made me a writer. She made this prancing little kid with his coloring books and his Play-Doh, she squashed the hell out of him, but she made him an observer of the world versus a participant. She made the little boy with an incredible will to survive — to learn how to read people, and most of all, how to read her emotionally, to know how to act, how to respond, and not be called faggot.

That made me a great observer of human nature, an introvert, and after all, what do writers do but look at the world and write about it. In some ways that was the forgiving moment. I was able to make sense of why my grandmother was in my life. I never had a forgiving moment with her face to face, as the poem describes. It was a great irony that she died without being able to speak. And the silence made me make peace with myself. That’s the only way I can make sense out of her. I don’t think I forgave her more than I just moved on.

Did you finally realize they can’t change, but you can?

That’s exactly right.

And in some way, they’re trying to protect you, from being hurt by people that think that way. Sometimes, it is for your benefit, and at other times for their standing within the community.

Trying to spare you. She used to say, “Parecerlo y no hacerlo” — Act like a faggot and not be one. As she says in the end, “If you act that way, you’re going to get it, whether you are or aren’t.” It’s how I was able to make peace with her ill-conceived world, the world she was trying to project onto me.

When I read I always tell the audience that every family has a relative that means well but doesn’t know how to give a compliment without insulting you, one relative that’s the thorn in your side. People are attracted to that poem not necessarily because of the queer issue, but because someone in their family has hurt them that way. They understand that despite how weird and bizarre that person was, it made for a real, complex relationship.

Why did it come from the grandmother and not the grandfather?

I don’t know, but friends and others that I’ve shared this with, it always seems it’s the women more. What I wanted to do in The Gulf Motel was examine those subtleties. Here’s my grandfather watching TV like The Rifleman about real men who kill and beat each other, while he’s scratching my back, and I’m falling asleep in his lap, so tender, so queer, so un-macho. The same with my father and this incredibly quiet affront of a man who is dying underneath his skin and underneath his silence, and yet there were moments when he was breaking out of that gender role.

And my mother — as you know in Latin families — always talked about machismo, machismo, and machismo. It’s the women who run the entire show. She is the matriarch and leads the pack. Even in the poem, it’s like she is the center of gravity. I haven’t quite figured out where my mother was in all this. My grandmother was not my mother’s mother. She was her mother-in-law. I guess my mom was just busy working. No one was there to protect me from my brother who attacked me emotionally. But my mother was kind of passive in that triangle, and she was in fear of my grandmother like everyone else.

I have a line in my play I-DJ where the protagonist says, “it’s not fathers that teach their sons machismo it’s mothers.”

It always seems to be that way. It’s like a man can understand loving another man. It’s just odd. In our culture I feel it’s really relevant. Even when I came out, my sister-in-law was the one that went nuts. My brother was all right. He was like — we kind of knew. My mother was a little more difficult.

In The Gulf Motel, I was looking back on my life and trying to explore, in a different way than I had in the other books, the intersections of cultural sexuality, culture identity, and my sexual identity and awareness. These things are braided tightly together. It wasn’t a miracle that after my grandmother died, I really didn’t come out, I came out to my mother — but it didn’t feel right until my grandmother died. There was something holding me back.

You’re talking about 18 million different stories and experiences. I’m not sure we’ve even explored that in queer literature. We often just bury these unique stories as society slowly accepts the idea of that type of storytelling. There are interesting stories to tell that are interstitched between the idea of sexuality, and it’s not just about being queer, but how being queer relates to other elements in your life.

It’s not the same for a Cuban-American kid growing up in the third world as it is to be an Asian-American kid who had an affair behind the laundromat. They are two different worlds — they may have some intersection, but they’re completely different stories. That’s what I’m excited about exploring now and what it did for me personally.

Let’s pause our conversation at this point. I’m eager for us to explore how you were able to write three distinct inaugural poems in a few weeks and why “One Day” was selected as the poem you read at the inauguration.

Agreed. You should have known when you get a Cuban talking …

In the memoir you state, “[I] leave the politics to the politicians — that’s their genre, not mine.” That raises the question of why Cuba as a political issue is absent in the three collections.

Having grown up in the 1970s in a politically charged city like Miami, my parents weren’t bitter exiles; they were middle-class people. They were hurt in other ways. But they chose to leave in 1968; they’re not as strident as the … first generation that left. Still the community at large was like: “Castro is a son-of-a-bitch.” “They stole this and they stole that.” “Cuba once was a beautiful paradise and blah-blah-blah.”

However, when you go to the history books, they’re almost complimentary about Castro, health care, and literacy. I realized at an early age that I was polarized — that perhaps history is between these two things. It’s a battle I couldn’t win. I realized that somewhere in the middle was the truth. My mother told me she grew up in a dirt farm home and that Cuba was dirt poor. So there were conflicting pieces of information. I didn’t feel I could take a stance because I didn’t know which stance to take. As I got into it more and more, I realized the truth is still in the grain. There are injustices on both sides of the fence in my little arena of the political Cuban-American community.

Besides that, I am just horrible at politics. I guess I’ve always been attracted to the consequences of history rather than the causes. I felt my job — as Campbell McGrath, my mentor, has always said, poets are in some ways historians. And it’s about leaving yourself out as well. What I was interested in was the human story, through being an emotional historian. Here is what I see in my community, Miami, my mother and father; here is what I see when I go to Cuba. And I’m fascinated by their individual lives and the consequences of history they have of themselves. I’m being political in the sense that I’m recording the effects of these political motives whether that means the Cuban exile community shooting itself in the foot, so to speak, or whether that means the Cuban in Miami can understand what it really means to live in Cuba with these old cars and homes, the bullshit image.

For me poetry was a more profound way to get to understand what it all meant. I never went that political route. I guess my muse comes from a different place. I get angry and pissed off, but it never comes through in the poetry. But what does come through is how we are all victims of politics. It becomes a history. When it came to writing the inaugural poem, I had a chance to show all this, but I opted to show the people and by reaching beyond the politics.

Things have really calmed down since. I was really surprised during the media frenzy surrounding the inauguration, not one person asked me about the embargo, not one person asked me anything politically charged about Cuba. I think it’s moving on to another phase, even reporters in Miami, it’s not touched upon. It’s reached a deadlock. Everyone is waiting for something to change. There are still some diehards, but I think my instincts were right. It’s not a good place to write about poetry. The politics I grew up around don’t excite me. I believe that is reflected in the poetry.

Your focus has been on the Faulkneresque postage-stamp area of Miami.

If you can capture one human accurately, you’ve done a lot. I also think of Robert Frost who focused on his region. One of the reasons he was so remembered and adored to this day is because he was imbued in the New England folklore of America, writing about the neighbors from what he knew and extracting the personal from the immediate experience. I definitely follow that.

“Good fences make good neighbors” has a lot of political charge to it.

I’m not an immigrant writer, but I am the son of immigrants, and I’m an immigrant myself who is a writer. You always worry if you’re writing in the context of your story, it’s not mainstream, and it’s not Robert Frost. When you’re writing, you’re always thinking, I’m going to tell my story about eating pork on Thanksgiving, but you’re also striving to pull out the transcendent meaning, to find some universal meaning within the story. I always try to write that way. It’s not just about cultural diaspora but about what is the base human emotion here. Everyone has a child, a stranger in their own home, a feeling of alienation, and a desire opposed to what the family traditions are. I think that has always been true. The poem I have to make is of other voices, of particular people in the small postage-stamp way Faulkner does — a poem pulled from my life experience, from my periphery of images and whatnot.

I read “Boston Strong” as a response to violence. Ditto the mention of Sandy Hook in your inaugural poem. Yet in the Boston poem there is no mention of the two young men — immigrants — who were later charged with the bombings. Were they ever in the poem or did you decide not to focus on them?

That poem was complicated for two reasons. I don’t live in Boston, and I didn’t want to come across as inauthentic. That’s why it is addressed in the second person to the Bostonian. I think I left it out on purpose. I didn’t want it to be about anger. I didn’t want it to be about revenge. Like the inaugural, I wanted to look at the higher and positive of all this madness and give us “this new spring.” Even though the occasion was a few weeks after the event, it was kind of a healing. I didn’t want to get into forgiveness or hatred because in a sense that belongs for the people of Boston to say those words or to express those things. It was a very difficult poem to write. I never found the room in there to discuss that. I was afraid there was going to be an immigrant backlash. The irony that an immigrant wrote a poem for Boston was interesting in itself. I never heard that we are going to close the borders, et cetera. So yes, I wanted to move ahead in time and not bring about anger, but instead some healing emotion.

Are you still uncertain as to why you were selected? Has anyone given you a clue?

Nope. The only thing that the president did say in the Oval Office — and it’s not in the memoir — was that my work was brought to his attention. We just drifted into something else so I didn’t ask — who? I didn’t want to pry. Was it Michelle, someone on his staff? I just think he felt strongly enough about my work that he approved my selection. So who that angel was I don’t know. I do know it changed my life forever. It’s almost like the MacArthur. You never know who nominates anybody. They just call you out of the blue. From stories I’ve heard from Sandra (Cisneros) and Ruth Behar [former MacArthur fellows], they have never had an inkling as to how it happened. No inaugural poet has ever written a memoir. I wonder if there is an unspoken thing among inaugural poets …

I think you answer it in the memoir: “Was it because I was Latino, from Florida, political, gay issues? It might be all those things.”

Assuming that the work is good, the deciding factor isn’t solely political, but my selection was appropriate in many ways. I was very proud to step up to the podium. I was glad to step into those shoes. It’s a balance of all those things. Why do we like certain poets? It has to do with the subject matter and what they represent, what their interests are, their concerns are, and their themes are. It comes together in one ball of wax.

Obama himself must have connected with the work on that level. I can see him asking the same questions of culture and negotiation, his coming to America as a child just as I did, and he’s had a more complex biography than I, with his moving here, moving there, going to Kenya, et cetera. He must have negotiated what he thinks America was. That’s part of the reason he selected my work. But hey, I’m no dummy. It’s a moment of great importance — and a lot of variables are at play.

The inaugural poet Elizabeth Alexander referred to her poem as “a praise song — A communal moment on the occasion of Obama’s inauguration.”

I’ve come to think of my poem almost as a prayer, a psalm. An invocation to appeal to the very ideals this country was founded on. Whether we behave like this every day or not, here’s the reality. We are all connected. We are all one people. We need to understand that. And we need to move forward together. It also felt like an anthem of this tangible, almost graspable idea that this country was based on. In a way, it is a praise song as well. It is for all of us.

How did you feel being asked to write three poems? To being vetted?

You know I didn’t ask why, but I also was the first inaugural poet that was asked to write three poems. I think that really had to do in part that they didn’t know me from Adam. And the other, I suspect from a very practical level they were a little behind when Elizabeth was selected, and their fear was that if they only asked for one poem, and it was a real stinker, they couldn’t ask me to write another one because they wouldn’t have time.

They really weren’t pressuring me to write three. They said perhaps you can submit one you’ve already published, but we’d like something original. But if you have something that you’ve written that you feel would be appropriate, we’ll consider that. They really wanted to make sure they got a good one from me. I welcomed the challenge, in the sense of — what it made me think. You can see, all three poems, how really different they are.

Absolutely!

It let me explore some questions about America that I hadn’t in my other poems. I didn’t get angry, but I suppose these things were going on. They were very gracious. And after I submitted two first, then the third one the following week, the White House got back and said, “We love the [last] poem.” I was like, is it a good poem or not? That’s the best poem? Is it the better of the three? Those things ran through my head. That actually was a little bit hairy. But then I fell more in love with the third poem. In a way, I’m glad they didn’t ask me six months before to write one poem. There is something to be said for the timed exercise.

It put your feet to the fire.

Pressure sometimes brings out the best in us.

Did you ever receive any feedback as to why they didn’t select the other poems? Or why they selected “One Today”?

I don’t think they had time for that kind of feedback. They did like “Mother Country” a lot. I remember them saying they wanted a more appropriate poem. The language that they used to convey this is very accommodating: “Well, no, you have to read this one.” “We still prefer the last one.” There is that kind of generosity the way they get back to you. They did catch a couple of typos but that was about it. It was kind of flattering, but I was like, are you sure? Is there a poetry workshop committee in the White House?

Of the three poems, “What We Know of Country” addresses all Americans in a precise, direct voice that welcomes dialogue. Its last line leaves an opening for us to engage in critical discourse. It asks where do we go from here?

Yeah, that one was a little braver and stronger. If anything, we can say it was more political. Right? We know we’ve messed up in the past, but we need to know what we’re going to do about it. It was a more direct idea that we need to work together. We need to put an end to this polarized divide in America. It’s almost like a married couple squabbling. There was more bite to that poem, a little more in your face, which is probably why they stayed away from that one.

Do you think because it addresses immigration and gay civil rights, it might have upstaged Obama’s speech that came before yours? Was that daunting?

After his speech, I realized why they chose “One Today” — it was a very inclusive message of moving together, hope, and possibility. More about the realities of the political arena. They liked all the poems at the end of the day. Some people were suspicious that Obama and I were in cahoots. He wrote his speech and I my poem and they were parallel.

You hadn’t read his speech but he’d read your poem.

That’s true.

The Latino and LGBT communities had high expectations when one of their own was selected to be the inaugural poet. Ditto the general public that was expecting you to bring a face to that diversity — more in your poetry — than just your handsome face at the podium. Did you receive any feedback in this regard afterward?

We were expecting a lot of feedback, no matter what. But there were no hate messages about me or about the poem. I think that community was just so proud. I had the right instinct — a gay, Latino man reading a poem to the country, it tickled people pink. I couldn’t even grasp the enormity of it. I was busy writing the poem, rehearsing it, trying not to screw up, get dressed nice, going through the motions of just doing it.

Afterward, at the Human Rights Campaign Ball, the crowd went absolutely nuts. Oh, shit! A gay guy just read a poem to the entire country. I realized what that meant to the community in and of itself. Without having to say anything directly or pointedly toward that. I told you how I used words like Colorado and Sierras with their Spanish inflection and how the presence of Latinos in this country goes back hundreds of years.

And yet, in “Mother Country,” we see a face of the Latino experience in America that we haven’t seen, and it still has the spirit of the American dream, the observation and wisdom of your mom when she says, “You know mi’jo, it isn’t where you’re born that matters, it’s where you choose to die — that’s your country.”

I wanted all three to be different facets of my writing, and my experiences, and how we can live in our country and be part of the union, so to speak. The poem about my mother is a very autobiographical poem. It was the easiest of the three to write. But even then, I had never seen my mother in that light. I had always seen her suffering in Cuba, but I never quite grasped the face of how immigrants are the most patriotic. They don’t take these liberties for granted.

Now that your shining moment has come, what are your plans to keep poetry a living part of our literary heritage?

I’m taking that message to all my readings and conversations with audiences — not only in the schools but also sort of reeducating adults about how poetry can connect in ways no other form can. I’ve been given this opportunity. I plan to take it on the road.

A poetry food truck on a Chautauqua circuit — that’s very cool!

I really have this dream, envisioning a poetry bus — big, huge RV that travels around the country filled with materials, going to schools, meeting with teachers, doing impromptu poetry readings, providing educators with a greater appreciation of how poetry works, and also acting as gathering place for local poets, introducing them to the greater community.

¤

LARB Contributor

Gregg Barrios is a playwright, poet, and journalist. He is a 2013 USC Annenberg Getty Fellow, and serves on the board of directors of the National Book Critics Circle. He was inducted into the Texas Institute of Letters this year. He is the 2015 Fall Visiting Writer at Our Lady of the Lake University. His work has appeared in Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, Texas Observer, Texas Monthly, Film Quarterly, San Francisco Chronicle, and Andy Warhol’s Interview. He is a former book editor of the San Antonio Express-News. He has received a CTG-Mark Taper Fellowship, a Ford Foundation Grant, and a 2013 Artist Foundation Grant for his theater work. His play Ship of Fools about Texas writer Katherine Anne Porter premieres this year in San Antonio’s Overtime Theater. He is collaborating with actor and filmmaker James Franco on a book of his experimental work in poetry and film.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!