Coens in Transition: Two Books on the Coen Brothers

Matthew Sorrento compares two recent books on the work of the Coen brothers.

By Matthew SorrentoJuly 29, 2022

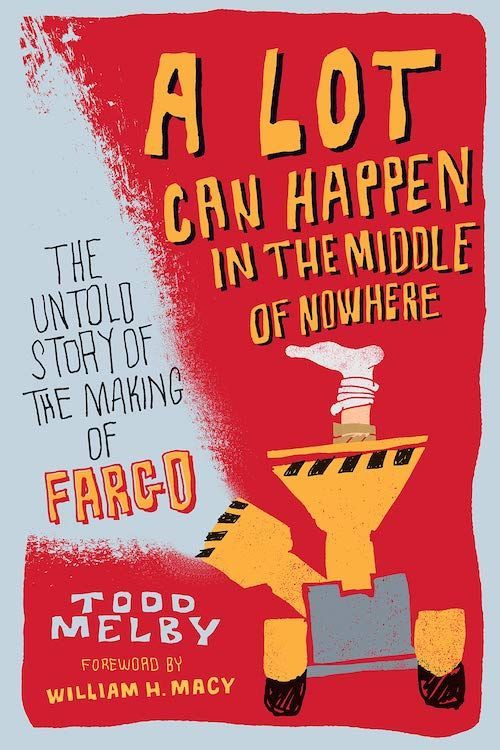

A Lot Can Happen in the Middle of Nowhere: The Untold Story of the Making of Fargo by Todd Melby. Minnesota Historical Society Press. 232 pages.

The Whole Durn Human Comedy: Life According to the Coen Brothers by Joseph McBride. Anthem Press. 118 pages.

WITH THE RELEASE of The Tragedy of Macbeth (2021) — Joel Coen’s first filmmaking project without his brother, Ethan — came the news that the Coen brothers’ split may be permanent. Longtime collaborator Carter Burwell announced just prior to Macbeth’s release that Ethan has lost interest in filmmaking. The news proved premature, with Ethan’s documentary, Jerry Lee Lewis: Trouble in Mind, making a surprise appearance this year at Cannes. (This archival project avoided the demands of shooting on location, which Ethan has cited as a major factor in his decision.) Although possibly just one of their trademark pranks, the current separation underscores the importance of The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018), the brothers’ last collaboration, which plays like a final survey of common interests.

If fans wish for more, the Coens’ filmography feels complete. From their strong debut, the neo-noir Blood Simple (1984), to Buster Scruggs, they continued to surprise viewers with a recognizable style both refined and cartoonish in its blend of humor and dread. The Coens’ second film (besides scripting for Sam Raimi on Crimewave, 1985), the comedy-caper Raising Arizona (1987), became a cult favorite with help from pay-cable rotation. The pair that followed, the quirky gangster epic Miller’s Crossing (1990) and the Buñuelian writer’s nightmare that took the Palme d’Or at Cannes (along with Best Director and Actor for John Turturro), Barton Fink (1991), proved their versatility. If The Hudsucker Proxy (1994) failed on its promise, the Coens returned with what was for many their most surprising film to date, Fargo (1996).

Two new books assess their career high points, neither volume completed before news of their breakup. A Lot Can Happen in the Middle of Nowhere: The Untold Story of the Making of Fargo (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2021) delivers a production history of what author Todd Melby describes as a “transitional work” for the Coens. With its critical success, which took the brothers by surprise, the film remains one of their most restrained stylistically, allowing new Coen-sian elements to emerge. The Whole Durn Human Comedy: Life According to the Coen Brothers by Joseph McBride (Anthem Press, 2022) focuses on their auteurist themes and preoccupations, a project the author began as a chapter in the author’s 2017 essay collection, Two Cheers for Hollywood. In his final chapter on Buster Scruggs (the only dedicated to a single film), McBride highlights another career transition, treating the Netflix original as a coda in a form ideally suited to the brothers’ sensibility: the anthology film. Addressing the recent news in an opening note, McBride’s study reads as a concise retrospective.

¤

Fargo seemed like a passion project for the brothers, with its setting near their childhood home (though the two had relocated to New York City early in their career). But Melby notes that the brothers launched the project while waiting for the cast of The Big Lebowski to become available. The circumstances proved beneficial, as Fargo allowed the Coens to experiment with a more somber visual style before returning to their more chaotic signature in Lebowski, released in 1998. Fargo’s observational treatment would serve the brothers well in numerous other projects, especially The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001) and No Country for Old Men (2007). The 1996 film also proved to be a timely entry in crime comedy, handling the genre’s dual demands in a manner more assured than Quentin Tarantino in the critically acclaimed Pulp Fiction (1994). A book dedicated to Fargo warrants some consideration of Coens’ intertextuality with other crime comedies of the 1990s. But thankfully, the oversight is one of very few disappointments in Melby’s text.

Melby proves himself an ideal journalist for this particular undertaking, having directed a 2016 radio documentary on Fargo with Diane Richard. He begins by focusing on the Coens’ early career to detail their writing approach, a risky move for fans who want to land right away in the snowy wasteland of Minnesota. A Coens script is always composed chronologically, with no end in sight, Ethan explaining how they write “scene A without knowing what scene B will be.” Their moment-by-moment approach implies why the brothers ran into problems scripting Miller’s Crossing, and how moving to Barton Fink, a love letter to writerly angst, served as a therapeutic reflection.

The Coens are historically hesitant to offer any additional details on their process, so Melby seeks out any evidence he can find. An early draft of the Fargo script from 1994, available from UCLA Library’s Special Collections, lacks memorable scenes featuring Mike Yanagita (Steve Park), who is after the pregnant Marge (Frances McDormand), and Mr. Mohra (Bain Boehlke), a bartender who offers a standout taste of local folk and showcases the Coens’ dialogue-writing prowess. This draft also includes background on two disturbing characters, Gaear Grimsrud (Peter Stormare) and Shep Proudfoot (the late Steve Reevis), for the latter a fascinating dream sequence at odds with the rest of the film (though akin to the one in Lebowski).

Melby also reveals key details about preproduction, such as McDormand learning her vocal delivery and mannerisms by lunching with supporting actor Larissa Kokernot (Hooker #1), going beyond the well-known anecdote about the actress creating a backstory with her on-screen husband John Carroll Lynch. While addressing work by well-known collaborators, like longtime cinematographer Roger Deakins and Burwell — both of whom helped to blend the observational and exaggerated in the film — Melby provides equal space to lesser-known contributors, including casting assistant Jane Drake Brody. Her guidance of actors during early auditions helped shape minor roles, telling one performer: “We’ve got to have a recognizable accent […] it’s best to err on the side of thick.” Her direction was, in many ways, as formative as the work from on-set dialect coach, Midwesterner Elizabeth Himelstein.

By recounting the shoot day-by-day, Melby depicts the film coming to life in an out-of-sequence schedule. After shooting in Minnesota, the production moved to North Dakota due, in part, to an unusually warm winter, requiring a lot of snowmaking. Here, Deakins’s cinematography captures a sense of isolation through his shots of barren landscapes, especially during the triple-homicide sequence and with Carl Showalter’s (Steve Buscemi) burying of the money. It is in these moments that Burwell’s score, with its key use of the Hardanger fiddle, resonates.

Melby addresses a significant fan base of Fargo, the true crime fans drawn to the parody of the genre. The opening disclaimer has long been ruled a hoax, which the Coens revealed to actor William H. Macy during the production. “You can’t do that,” argued Macy, who also contributes a preface for Melby. A Lot Can Happen recounts real crimes local to the Coens’ childhood home of St. Louis Park, Minnesota, and prominent in local press as possible inspirations: the 1963 murder of Carol Thompson in St. Paul by her husband, and the 1972 kidnapping of Virginia Piper, the event most like the one in the film. While these didn’t involve a woodchipper, one Connecticut murder of a flight attendant did, with her pilot husband arrested in 1987, the year of the film’s setting.

The author highlights viewer response, both national and local, where the portrayal of Northcentral folk has been adored and resented. CBS attempted a series in 1997, starring a pre-Sopranos Edie Falco as Marge, but the pilot failed to go to series. Noah Hawley’s FX series (2014–present), however, has been a success, with a fifth season currently in the works, though Melby sees it mainly as an extended payday for the brothers. Fargo proves to be one of the greatest Coen legacies, equal to popular worship of “the Dude.”

¤

In his discussion of Fargo, Joseph McBride describes Marge’s quest as “a bracing antidote to the viciousness of the killers she brings to justice.” Her involvement creates a “melancholy bewilderment” in line with No Country’s Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones). McBride connects these two films via a common figure for the Coens: the “beloved moron” (i.e., Macy’s Jerry and Llewelyn Moss [Josh Brolin] in No Country).

Known for his work on classical Hollywood, McBride’s recent books include one on Billy Wilder and an updated version of his 2006 text on Orson Welles, with whom he collaborated (even starring in Welles’s The Other Side of the Wind, completed in 2018). The Whole Durn Human Comedy is a nice surprise, a lively study that avoids the trendiness of many books on the subject (why try to match wits with the Coens?).

Though keen on the unlikely humanity in the Coens’ films, McBride sees a noir anxiety underlying their work, as well as an attention to Hollywood genres past. Preston Sturges’s Sullivan’s Travels (1941), a very human comedy, serves as an urtext for the Coens, most obviously to O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000), named after the film that John L. Sullivan (Joel McCrea) tries to make. McBride shows the Coen brothers’ films to be “volatile mixtures” of registers and styles, a fruitful approach overall, though not always successful. Like Melby, McBride traces their sensibility to literary sources, including James M. Cain and Flannery O’Connor, the latter of whom Ethan has cited in interviews, along with critic Jonathan Rosenbaum.

For McBride, the bleakness of these influences can go too far. If some entries misfire by relying on goofiness, like Hudsucker and 2016’s Hail, Caesar! (both, coincidentally, spoofing the 1950s), the author singles out others as relentlessly grim. On occasion, his remarks read like overstatement, describing A Serious Man as a “one-note parade of misery” that “take[s] the easy route by loading the dice against” its protagonist, as the Coens “chuckl[e] darkly behind the camera about life.” (This could just as easily describe Burn After Reading [2008] or even Lebowski.)

But when the Coens are at their best, they deploy caricature, with help of an alienation effect, to reveal life as generally cartoonish and absurd. McBride singles out Barton Fink as an effective, if savage, Hollywood satire with literary echoes of Nathanael West. But even Barton proves “volatile” in distorting historical figures and their “complexities and talents” (in particular, the portrayals of Clifford Odets [Turturro] and William Faulkner [the late John Mahoney]).

The book counters Coen detractors, like J. Hoberman and Ella Taylor, who resist the filmmakers’ genre bending. Taylor complains that the Coens degrade their characters to “affirm their own superiority,” but McBride replies that these faults make them more human, not less. And in response to a similar criticism from Hiram Lee of the World Socialist Web Site, McBride cites the strengths of the Coens’ sociopolitical satires, defending the brothers’ use of racial and regional characterizations which, some contend, the Coens exploit to demean their characters.

McBride’s chapter, “Skewed Perspectives,” offers one of the best assessments of Coens’ visual style around. Beginning with paraphrasing a complaint, like most of his chapters, McBride notes: “The Coens’ elegantly controlled visual style serves as a counterpoint to the deliberate messiness of their characters’ behavior and the filmmaker’s own fondness, inspired by Raymond Chandler, for intricate plots that mosey into the nonsensical.” Like the brothers’ general use of bold contrast, the synthesis allows performers to produce unique creations in a blend of “control and freedom.”

By singling out weak points and blind spots in A Serious Man and Inside Llewyn Davis (and its superficial treatment of the folk music tradition), McBride positions Buster Scruggs as the platonic ideal of the Coen worldview, his closing chapter treating the film as a worthy swan song for the pair. Here, the Coens incorporate disparate modes, which McBride argues they often struggled to achieve in their “highly uneven” features. With Buster Scruggs, they deliver a career-long goal, a fulsome mediation on mortality and what follows. Though a traditionalist in many ways, McBride commends the freedom of streaming (Buster Scruggs being a Netflix original) for offering the Coens this platform. The film shows their strongest use of genre blending, via adaptation for some segments, employing the Western into fresh revisionist modes while moving into newer registers, including the straightforward horror short “Meal Ticket” and the matter-of-fact tragedy “The Gal Who Got Rattled.” For McBride, Buster Scruggs captures the sense of promise that, as of now, may not come to be.

¤

LARB Contributor

Matthew Sorrento is editor-in-chief of Film International and Retreats from Oblivion: The Journal of NoirCon. He has published widely on genre cinema/television, documentary film, crime fiction, and genre poetry. He teaches film and media studies at Rutgers University in Camden, New Jersey.

LARB Staff Recommendations

On Privacy, Paranoia, and Genre

Harrison Blackman looks at three recent books about privacy, surveillance, and film aesthetics.

Cinema, Theater, and the Art of Perpetual Transformation in Joel Coen’s “The Tragedy of Macbeth”

Julia Sirmons considers the long-running relationship — at times rivalry — between theater and cinema through the lens of Joel Coen’s “The Tragedy of...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!