Check the Doors: On Alexandra Oliver’s “Hail, the Invisible Watchman”

Maryann Corbett celebrates the appearance of “Hail, the Invisible Watchman,” a new collection of poems by Alexandra Oliver.

By Maryann CorbettMay 2, 2022

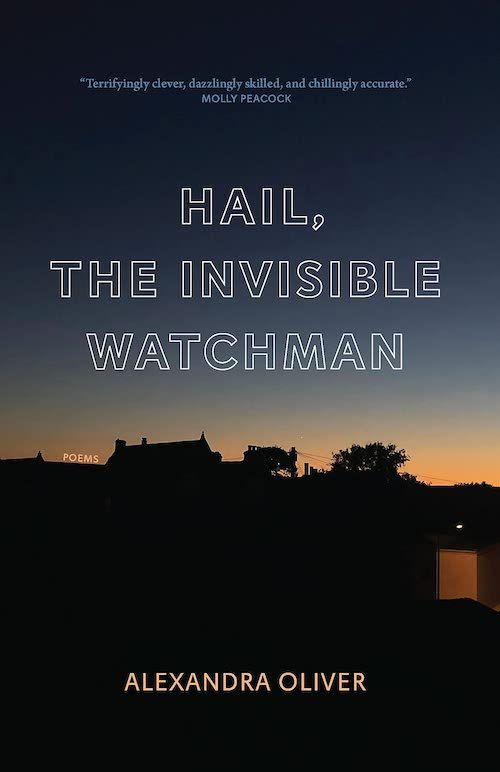

Hail, the Invisible Watchman by Alexandra Oliver. Biblioasis. 80 pages.

THEY’RE ALL HERE in her newest book, the formal and metrical pleasures that earned critical praise and prizes for Alexandra Oliver’s Meeting the Tormentors in Safeway and Let the Empire Down. But Hail, the Invisible Watchman is different from those books. The disturbing themes that appeared in the first two collections — the struggles of girls and women, domestic violence, class striving, escape from a constraining past — were relieved by the occasional flash of joy: the antics of a child, the rumpus of a Fellini film festival. Hail, the Invisible Watchman is dark and tangled, even when it hooks the heartstrings and pulls.

Watchman is actually three works in conversation. One is a collection much like the earlier books, but tighter thematically. The second is a narrative of family tragedy, told in the voices of its characters and in an assortment of verse forms. The third is a commentary in sonnets on a much-disputed novel called Hetty Dorval.

The opening section, called “The Haunting of Sherbet Lake,” is the one most like Oliver’s past work, but with more concentrated sadness and anger. Fans of the earlier books may remember the place name “Sherbet Lake” from Let the Empire Down. It’s the native place, the family-of-origin hometown full of rigidities and limitations, which has to be escaped, even with regret.

The poems in this section feel personal, but the group is studded with other personas. Here in Sherbet Lake are the Old Stock, controlling and manipulating and excluding (“Song of the Doyenne”), along with the strivers who are still striving (“Young Politician at a Rotary Tea Club” and “Hollywood. North.”) and the ones who have definitively failed (“The Announcer”). Here are the outcasts and misfits: poor, aged, lunatic. Here too is a longing for completeness that life may never be able to satisfy, the longing we soothe by shopping (“The Lipstick Effect”) and by seeking again and again the intense friendships of youth, finding only the superficial, as in “The Creatures”:

You get the guy who sees you as a prize,

a gunner in some heartless female army,

and, drunk, you ask the office to your place

one shimmering night, after the Christmas party,

then stand at the balcony waiting as no one arrives,

as the mud below rattles its diamond tail

and hisses indifferently, as if to say

Save yourself. Save it all.

Slowly back away.

It’s the resisters and misfits who have Oliver’s sympathy and whose stories she tells most wrenchingly. She favors especially the young and female, and the poems about them are some of the most interesting. “The Last Straw of the Last Duchess” is a particular example of the mixed tone Oliver often uses. Those who know Browning’s “My Last Duchess” well can enjoy the zing of allusion after allusion: the title, the rhyme scheme, that opening line, Fra Pandolf, even Claus and his bronze seahorse. Uttered in the voice of a modern, bored teenager, these classic references look on their surface like parody, but the huge anger is clear: “If I weren’t here and painted like the dead / I’d hurl that fucking sea horse at his head.”

The source of the book’s title is another poem about young women, “The Vampire Lovers”:

Hail, the invisible watchman,

silent and pale as a swan,

older than anything human,

spectral and silver and silken,

curled in the wakening dawn.

Why were the daughters so fearless?

Why did they go to the gate

and why did they dare to be careless —

didn’t they know they were bait

for him, the invisible watchman?

While it’s clear that this watchman is the dangerous tempter, that first line hints hard that the protecting forces — parents, teachers, elders, status systems — are watchers as well, haunting, posing a different sort of threat.

That problem of freedom sparring with middle-class expectation holds the spotlight in the book’s second section, “The Blood of the Jagers.” Here the collection begins to look different from Oliver’s earlier work, less like memory and more like fiction. A narrative in 12 poems, the section pulls us along with the voices of alternating first-person narrators: a mother, daughter, and daughter-in-law. The women have control of the story of the men’s failings.

Tracking what happens to whom is part of the enjoyment of reading, and a reviewer can overdo in explaining. The section’s next-to-last poem, “Best Practice,” is a summary in crisp, inventive rhyme. It’s a meditation on conformity in conflict with a freedom that endangers everyone near it — especially the women:

We thought it would be over soon enough.

He’d listen to the facts and move along,

find a job, a house, someone to love,

but we were wrong.

The guys we knew from way back when went clean;

our much sought-after punk lords of misrule

took up cycling, ran a snow machine,

went back to school

[…]

We told ourselves that maybe they were sellouts,

but, though they thickened up, becoming squares,

a part of us inside was somewhat jealous.

The God that spares

did not spare him. He wouldn’t ever soften;

he curled his evil into my life and yours,

and that is why our mother says so often,

Check the doors.

By this point, it’s clear that the book is a knot of conflicting needs. The freedom that longs for a life outside the locked gate is the same freedom that does terrible damage. It’s the threat that has us constantly checking the doors.

The book’s third section flips the perspective again. Titled “Clever Little Dragon: On Hetty Dorval,” this section is another narrative in verse, based on a 1947 novel probably best known to Canadians. This is the most demanding section for the reader and the one most in need of its back story. A long note explains the critical disputes about the novel: Is Hetty Dorval a dangerous older woman from whom the girl Frankie needs to be rescued, as most critics have claimed? Or is Hetty simply a woman who chooses to live life on her own terms, a victim of social ostracism and class prejudice? Is Frankie the guilty one in eventually abandoning her? Oliver takes the latter view and presents it in 14 sonnets, told mostly in Frankie’s voice — not really enough space for the novel’s complexities, but enough to make clear that Frankie’s rejection of Hetty is an evil. In the closing sonnet, Hetty and her third husband, who is Jewish, are stranded in Vienna as Nazism begins to close in:

[…] If love and Lytton really mattered,

if friendship plodded on as it was able,

maybe this wouldn’t have happened. The neighbor woman

pointing her finger (Juden! Juden!), the door

kicked in, the muffled sound of human

consternation. Frau Stern meanders into her war,

light to a fault, diffused, unknown, misread

as flocks of fleeing geese scream overhead.

Of Oliver’s three Biblioasis books, Hail, the Invisible Watchman is the most focused on the problems her poetry grapples with, but it has the strengths of the work that went before it. One can’t review an Oliver book without praising specifically her skill as a formal poet. Apart from the few critics who feel obliged to sniff at rhyme and meter, readers in Canada (mostly) and elsewhere (too few) all point to her lyric control. But what I most wish other formal poets would learn from Oliver is the usefulness of meters other than iambic, meters too many of them ignore. Oliver is so devoted a fan of those other metrical tools that she has edited, along with Annie Finch, an anthology of poems that use them. (Full disclosure: it contains one of mine.) The triple meters especially — dactyls, anapests, amphibrachs, often in mixtures — show up often in Oliver’s work. And they work for what she has to say. It’s a truism among poets that the duple meters, the iamb and the trochee, are the meters of speech, while the triple meters are those of song; too often we think of the triples as suitable only for light verse and pleasant subjects. To disprove this notion I offer “Seventeen,” a lament on the various pangs of parents concerning children’s sports:

Seventeen scissor their legs on the mats,

slashing the air, like quick little knives.

They are told to develop their glutes and their lats.

(The fathers remember their whey-coloured wives.)

Seventeen shoulder their bags to the courts —

their elders assure them it’s not about winning —

but wince, as the possible pecks at their hearts.

(The fathers are fat and their forelocks are thinning.)

[…]

Seventeen eight-year-old creatures are moving;

they climb into vans. As if speaking to God,

they venture, I think that I’m really improving.

The fathers hit gas and devour the road.

We chuckle at those fathers, but we wince at their discomfort, too, and we ache for all this probably hopeless effort. In this poem, the overlay of song on sorrow only deepens sorrow, as it does in the most moving lyrics of Stephen Sondheim and the albums of Joni Mitchell. If the formal poems in Alexandra Oliver’s Hail, the Invisible Watchman are dancing in chains, they’re probing consciences and wringing hearts at the same time.

¤

LARB Contributor

Maryann Corbett is the author of five books of poetry, most recently In Code (Able Muse, 2020). She is a past winner of the Richard Wilbur Award and the Willis Barnstone Translation Prize. Her work appears in journals on both sides of the Atlantic, on the websites of the Poetry Foundation and American Life in Poetry, and in The Best American Poetry 2018.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Putting Things Back Together: On Alexis Sears’s “Out of Order”

Maryann Corbett is awed by “Out of Order,” Donald Justice Poetry Prize–winning collection by Alexis Sears.

The Pursuit of Awe: On Aaron Poochigian’s “American Divine”

Maryann Corbett is awed by “American Divine,” a new collection of poems by Aaron Poochigian.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!