Caring Versus Caregiving: On Talia Schaffer’s “Communities of Care: The Social Ethics of Victorian Fiction”

A new book about caregiving in Victorian novels sheds valuable light on the crisis of healthcare today.

By Rachael Scarborough KingFebruary 11, 2022

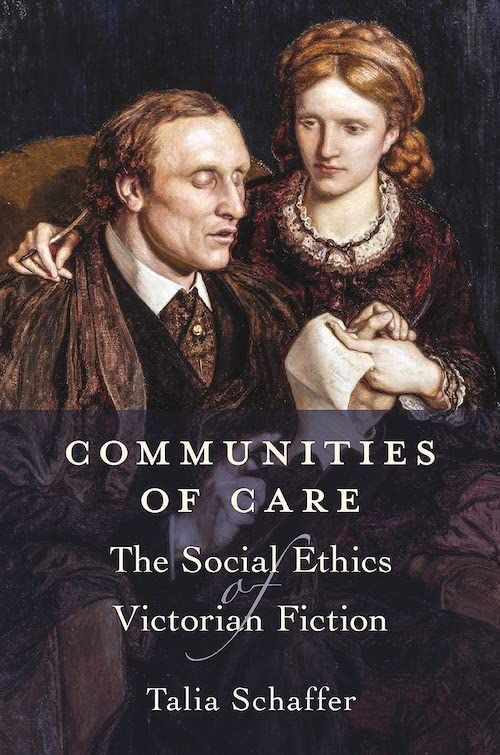

Communities of Care: The Social Ethics of Victorian Fiction by Talia Schaffer. Princeton University Press. 296 pages.

IN JUNE 2017, journalist Kayla Chadwick posted an op-ed in The Huffington Post whose title — “I Don’t Know How to Explain to You That You Should Care About Other People” — captured the liberal zeitgeist of the early Trump presidency. Written during the debate over the Republican tax cut plan, the piece contrasted apparently caring liberals with callous conservatives. Of those who do not support, for example, a higher minimum wage, well-funded public schools, or universal health care, Chadwick wrote: “Our disagreement is not merely political, but a fundamental divide on what it means to live in a society, how to be a good person, and why any of that matters.” She cast political differences as moral choices that divided good people from bad.

Chadwick’s essay took off and continues to be shared on Twitter whenever the Republican Party does something especially uncaring, which is often. But as it turns out, Chadwick was not the originator of the “care about” formulation of the article’s title. In January 2017, author Lauren Morrill tweeted of the Republican effort to kill the Affordable Care Act: “My biggest problem in these ACA debates? I don’t know how to explain to you why you should care about other people.”

Chadwick’s article never credited Morrill with the phrase and HuffPost declined to update the piece, likely because it appeared on their now-defunct contributor platform, which did not vet contributions. While Morrill is periodically credited for the quote, it continues — in a variety of slightly altered wordings — to circulate in connection with the HuffPost article.

Then, in June 2020, the narrative took another turn, when the phrase began being attributed on social media to Dr. Anthony Fauci. Fauci had said something vaguely similar — “Now is the time, if ever there was one, for us to care selflessly about one another” — and the two quotes were apparently conflated. Given that the two original attributions came from highly partisan sources, this conflation played into the politicization of the pandemic, and of Dr. Fauci, that was occurring at precisely the same time.

Talia Schaffer’s new book, Communities of Care: The Social Ethics of Victorian Fiction, is about caregiving in Victorian novels, but it helps illuminate this mini-saga of how our society understands care today. Schaffer shows that the stated aim of the first two versions of the quote — convincing conservatives to “care about other people” — is misplaced. Care, she argues, is not a feeling but an action. Caregiving, she writes, “differs from, and need not derive from, ‘caring,’” and she goes on to “argue for caregiving as one of the most fundamental forms of human relationality.” Caregiving and caring often get mixed up together because we are suspicious of care that comes without caring — as all versions of the “care about” quote emphasize. But targeting people’s feelings in the political arena and congratulating ourselves for “caring” may deflect from the hard work required to change policies that would support caregiving with or without a feeling of care.

Schaffer might also argue that the participants in this exchange did not extend care to one another. Caregiving, she points out, is a framework that crosses the borders between texts, authors, readers, and critics. Citational practices, for example, can be understood as a form of caregiving — interpreting, framing, and circulating another’s words — and in this case, Chadwick, the author of the HuffPost piece, did not adequately cite Morrill’s tweet. Morrill has made clear that she resents this lack of citation and asked HuffPost for credit at the time. In an interview with Oprah Daily, she noted that the experience influenced her to be more careful about sharing quotations online, saying, “I don’t share anything anywhere unless I know the credit for it because I know how disheartening it can be.” Chadwick wrote about caring but did not extend care to Morrill’s words.

The distinction between care as a feeling and caregiving as an action is a crucial one for our political moment, but Schaffer shows how the conflation of the two arose from Victorian shifts in medical understanding, and how those changes were shaped by the era’s literature. She takes as her main case studies four Victorian novels: Charlotte Brontë’s Villette (1853), Charlotte Yonge’s The Heir of Redclyffe (1853), George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda (1876), and Henry James’s The Wings of the Dove (1902). Offering careful historical context, she argues that the Victorian period was a crucial era for caregiving because it saw the medicalization of disability and the professionalization of caregivers. The period’s literature reflected this reality but also, and perhaps more revealingly, offered an imaginative alternative to the new medical regime. “This is a literature that centrally thinks, and mourns, about care,” Schaffer writes, as Victorian fiction often depicted idealized care communities and/or low-quality paid care, demonstrating a “nostalgia for the enmeshed community.” Victorian novels not only memorialize an older model of caregiving but also provide examples of how strong care communities could work then and now, if we had the resources and will to move from our individualized understanding to a more holistic one.

Schaffer’s grounding in ethics-of-care theory allows her to range over time periods, across the borders of novels and real life, and between fictional characters and their authors and readers. Less than half of the text consists of the standard one-novel-per-chapter academic structure, with the rest outlining a theory of caregiving in both literature and life, and even at times offering advice for how we can become better caregivers in our own lives. Schaffer’s central object of analysis is the “care community,” a unit of “midrange scale” that draws together caregivers and cared-fors in ideally egalitarian, discourse-based groups. Victorian characters, she writes, are always arranging themselves in care communities, but such groups can also move beyond the bounds of the text to draw in authors, readers, critics, and other books.

As Schaffer points out in her preface, it is not often that a literary critic working in a historical period writes such a timely book. “I’m a Victorianist,” she notes. “I’m not used to writing on a topic that is dominating the news. So it was strange for me to discover that care was everywhere in 2020.” As schools, daycares, and universities closed down, and people were forced to quarantine in their homes, the lack of caregiving threw many families into crisis while also drawing attention to how little support existed pre-pandemic. The caregiving shortage revealed how much our society relied primarily on women’s caregiving, both the unpaid work of mothers and wives and the paid labor predominantly of women of color. As sociologist Jessica Calarco put it — in another quote-turned-headline that became a viral phrase — “Other countries have social safety nets. The U.S. has women.”

Communities of Care faces a problem common to historicist criticism, raising the question of why we should turn to Victorian fiction to understand our contemporary interest in caregiving. Schaffer clearly anticipates this line of questioning and justifies her focus in a number of ways. Because, as she writes, ideal care communities are difficult to maintain and rare to find, we may see them more clearly in fictional representations than in real life. “Perhaps the real question,” she says, “is not why I focus on the nineteenth-century novel, but rather, what can the nineteenth-century novel do for us? What might this particular cultural construct reveal to us about how care works in communal settings and about the history of care relations?”

Moreover, she notes that, as a literary critic, her particular caregiving skills involve her specialized training as “a close observer of textual representation and an analyst of cultural patterns.” She usefully defines caregiving (as opposed to care) as “meeting another’s need” and explains that she felt the best way she could turn her “critical skills to our current need was to use them to build a kind of reparative reading we could use, a rigorous and persuasive protocol.” This statement underlines the scholarly modesty — a description I deploy as sincere praise — that characterizes the book’s multiple critical interventions.

For example, Schaffer’s discussion of paranoid versus reparative reading revitalizes the latter category, showing how it can be an incisive methodology, despite being often caricatured as uncritical appreciation. Likening paranoid reading to “the diagnostic medical gaze” that flattens individuality, reparative reading becomes a form of caregiving that cares for the text without necessarily caring about it. Repair, she writes, creates a bridge to the past by inhabiting older modes while also noting their breakdowns and divergences. “If we want to do reparative reading, then,” she writes, “we need to embrace a carefully attuned relation with each particular text in which we can value what is broken, be patient with the past, and repair it to survive for future others to enjoy.”

Although she does not push the argument, this is a method that can answer many of the challenges faced by scholars in historical fields as we grapple with the problems of presentism — the problem of supposedly “judging the past by our own standards.” Even as we read a text from our historical standpoint, we must make an effort to see it on its own terms and to use our writing to connect those two perspectives across time and into the future.

Schaffer’s discussion of public sphere theory — an unlikely critical framework for analysis of caregiving — is similarly reorienting. Jürgen Habermas’s foundational work in the field drew a border between political and domestic concerns, although Habermas emphasized, in The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (1962), that the public with which he was concerned was “the public of private people making use of their reason.” Schaffer mostly agrees with this schema, conceptualizing “the public sphere as a politically oriented paradigm and the care community as a personally oriented paradigm.” But of course, there are not hard-and-fast lines between these arenas, which are not strict identities but “orientations that overlap, engage, and ramify.” Both the public sphere and the care community are “imagined communities that operate through discourse,” are normatively open to all regardless of status, and develop over time. Using public sphere theory to understand caregiving, then, refines our knowledge of how public spheres work while clarifying Schaffer’s central distinction between caring and caregiving. The action of caregiving does not need to align with the feeling of care, meaning that we can read external behaviors as evidence of caregiving without needing to fathom hidden inner feelings.

This focus on the external rather than internal is also key to Schaffer’s theory of character. By focusing on care communities and networks, she shows the limits of realist theories of the novel that distinguish between deep major characters and shallow minor ones. As she points out, allegorical types coexisted alongside developed individuals in 19th-century novels, with many characters displaying features of both categories. Caregiving characters often reveal a mismatch between external behavior and internal feeling. In extreme cases, as with Villette’s Lucy Snowe, they baffle and resist the reader’s attempts to discern a true self. Turning attention to the caregiving within a text can sidestep insoluble questions about the truth of a fictional narrative: “Instead of asking who a character truly is, we might start asking who cares for whom, and how — a question that may lead us to disregard the boundaries of the text.” Indeed, I felt myself — an English professor but not a Victorianist, neither a practitioner of reparative reading nor primarily a scholar of the novel — interpellated in these moments. I have written a lot about caregiving lately, as Congress has debated, and now apparently abandoned, a major social infrastructure plan that would have offered significant new benefits like home health care for people with disabilities, paid family and medical leave, and universal preschool.

I have a particular perspective on these issues because my husband is seriously disabled due to the neurodegenerative disease ALS, and we rely on full-time caregiving for him to be able to live at home with me and our young children. For me, caregiving is much more of a personal than an academic interest. This is what drew me to Schaffer’s book, which is outside my current research field. My husband is a prominent health-care activist with nearly 200,000 Twitter followers, and we have been featured in glossy videos and photo spreads in The New York Times, on ABC News, and even in People magazine. A documentary about him has been nominated for several major awards. I bring this up because I often feel that I am playing a social type in these stories: loyal wife to sick husband, mom holding things together while her spouse pursues his life’s work. And I very much understand that caregiving does not always include caring; I love my children, but I don’t love being the only parent able to get up with our early-bird daughter at 5:30 a.m. every day. We live these roles in our own way, but they are still familiar to us as roles; we are both individuals and types. Schaffer shows how caregiving connects us to one another through our actions and through the roles we move in and out of, and how we can resist the modern suspicion of external behaviors that do not precisely align with inner feelings.

The book’s final major move, then, is to enlist the reader as a fellow caregiver. Schaffer shows how academic structures can be communities of care in three primary ways: by seeing critique as care, by understanding citational practices as caregiving, and by valuing service work in the academy. Literary scholarship, she notes, is itself “motivated by a scene of care: a text that cannot speak for itself and needs us to step in.” She argues that, to be true public goods, universities should orient themselves to the standard of “meeting another’s need” that she has established: “I am proposing something like a mission statement, but for care. You might ask: for whom does my institution really care?” Schaffer shows in a practical way how we can use our skills as literary scholars to effect the kinds of changes in academic life that we want to see, moving from our individual research practices to our advocacy at the campus level, and beyond. Many of us may not feel care from our institutions, but we can demand that they give care to the students, alumni, faculty, and staff who make them work. Caregiving has traditionally been understood in the realm of feminized feeling; Communities of Care shows how it can be a call to action.

¤

LARB Contributor

Rachael Scarborough King is associate professor of English at the University of California, Santa Barbara. She is the author of Writing to the World: Letters and the Origins of Modern Print Genres and editor of After Print: Eighteenth-Century Manuscript Cultures. Her work has appeared in The Nation, Aeon, Avidly, and the Los Angeles Review of Books Quarterly Journal.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Frontiers of Form

Rachael Scarborough King on three books that consider the way forward for New Formalism.

Medicine and Activism in George Eliot’s “Quarry for Middlemarch”

How one of the greatest English novels emerged from research into a disease outbreak.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!