Buster Keaton and the World of Objects

Given the choice between a book and a baseball bat, there is no choice for Buster. He’ll take the bat every time

April 19, 2011

“The world is the totality of facts, not of things.”

— Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

THE FAMOUS OCCASION, LOS ANGELES 1929: after a party in Buster Keaton’s Beverly Hills villa, Buster persuades Louise Brooks and Bill Collier (who’s also sometimes known as Buster) to drive with him to Culver City, to the MGM lot where the studio has provided him with a bungalow, christened Keaton’s Kennel. It’s a big deal for the studio to give a star a bungalow. It shows how much they value him, what an asset and moneymaker he is for them. The place has become a party house, a drinking den: we are, of course, still in the depths of prohibition.

At the bungalow, Louise and the two Busters have a nightcap. Keaton slips out of the living room and returns with a baseball bat, which is not so strange in itself. Everybody knows how much Buster loves his baseball. The living room is lined with glass-fronted bookcases. Keaton takes the bat and systematically smashes every pane in every bookcase, puts the bat aside, sits down, says nothing. Brooks and Collier say nothing either. The three of them carry on drinking. Another Hollywood evening.

Something to bear in mind: the bookcases are empty. Buster isn’t much of a reader. Arguably he wrote one more book than he ever read. His name appears on a ghostwritten autobiography, My Wonderful World of Slapstick, a title that I’d like to believe was awash with irony, but I really don’t think it is. Keaton dictated the book to Charles Samuels and never so much as looked at the manuscript. Why would he need to? What good would it do? By his own account he only ever had one day of schooling in his whole life. He played the class clown and was told never to come back. He was all too happy to do as he was told.

Given the choice between a book and a baseball bat, there is no choice for Buster. He’ll take the bat every time. When he’s working on a movie sequence and they’ve run out of ideas, he yells, “Throw down your pencils, pick up the bats.” The crew sets up a baseball game. By the second or third inning, probably with a runner on base, Buster will throw his glove in the air, yell, “I got it!” and they can all get back to work. Must have been frustrating for the guy on third.

You know where you are with a baseball bat. It’s not that way with books. (It’s not that way with many things.) And sometimes, when it suits him, it isn’t even that way with baseball bats either. There are times when, for the sake of a laugh, or a charity game, or in the movie One Run Elmer, Keaton will put on a show with a bat made of plaster of Paris, or he’ll pack explosive in the tip so that it blows up on contact with the ball, but that’s OK: this is only appearance. It’s all part of the show, and he’s the one running it.

And that’s how it is with the rest of Buster’s universe. Things are clearly not to be trusted. The chair will collapse, the plank will hit you in the face, the gun will misfire, the car will die on the railroad tracks, the boat will sink, the balloon will escape gravity and take you with it. The only answer is to make sure those objects are in fact props. Once things are scripted, then everything’s all right, he’s in control, the objects will do his bidding. People less so.

¤

It starts before he’s born. “The Man Who Broke Chairs,” “The Man with a Table.” These are the unpromising titles for his father’s stage routines. Joe Keaton, an acrobat, comic, dancer, father to Buster, then to Louise and Harry (more usually known as Jingles), husband to Myra; all of them part of the act at one time or another, an act that belongs to a tradition harking back even before vaudeville, to the medicine shows.

Father and son share the same first name, so before long the kid becomes Buster, a name of uncertain provenance, but almost certainly not given to him by Harry Houdini, as sometimes claimed. Buster isn’t born in a trunk, but he comes close to dying in one. As a baby, his parents keep him in the wings during the show, set him down in an open trunk, using it as a kind of crib. One time, while his parents are on stage doing their act, a stagehand accidentally brushes against the trunk and doesn’t see the lid fall shut. When Myra comes into the wings for a costume change she opens the lid to find the baby inside, half-suffocated. He survives, of course. They give him a couple of sips of beer and soon he’s just fine again. He’s a resilient little Buster.

A couple of years later he investigates a laundry mangle and gets his right index finger trapped between the rollers. They have to dismantle the mangle to free him, then they have to amputate the top joint of the finger. Maybe he’ll be safer on stage.

He makes his first public appearance at the age of nine months, when he crawls onto the stage in the middle of one of Joe’s monologues. Maybe Joe planned it all along. In any case, the kid is cute as all get-out, receives a ton of applause. He’s in show business before he knows it. By the age of three he’s a crucial part of the act; by the age of seven he is the act: “Buster Keaton, the Human Mop,” “The Little Boy Who Can’t Be Damaged.”

Buster’s role on stage is to be a pesky little kid, to subvert and infuriate his father who takes angry, comic slapstick revenge. Consequently Buster is treated like a thing, an object that’s kicked, hit, thrown around, tossed across the stage, against a wall or piece of scenery, or sometimes into the audience. His mother sews a suitcase handle into the back of his jacket so he can be picked up like a piece of luggage. He learns how to land. He learns how to fall. He learns a great many things. If it hurts he mustn’t cry. If he enjoys it he mustn’t smile. It’s not funny if he does either of those things. He learns the value of stoicism and blankness. He also knows that his father will hit him that much harder if he spoils the laugh. He’s equally aware that his father is a drunk and that his timing and coordination will be sloppily unpredictable.

In Syracuse the audience is especially rough. They mock Myra’s saxophone solo, but Joe knows how to deal with them. He singles out a particularly loud band of hecklers — Yale men — picks up Buster by the handle, says, “Tighten up, son,” and flings the kid feet-first through the air, into the audience, right into the hecklers. Buster’s feet smash into the face of one of them, breaking his nose and destroying his hat. At the end of the week the theater manager deducts the price of the hat from the Keaton family’s wages. “Look here Joe,” the manager says, “you can’t use your son as a club to beat the spectators.” Joe still reckons he can. Child abuse? Of course. The audience loves it.

¤

Buster discovers he’s mechanically adept. He works on automobiles, buying his first car when he’s 14 years old: a “Browniekar” with a three horsepower, single cylinder engine — “the most popular, instructive, and health-giving device ever placed in the hands of the younger generation.” It costs 250 dollars and he pays for it in cash at Macy’s. His origins may be humble, but by now the family is far from poor. When his dad buys a boat (named Battleship), Buster takes out the upright boiler and replaces it with a gasoline engine.

He has a gift and an instinct. He rigs up comical Rube Goldberg-style contraptions for a notoriously fat, lazy family friend, Ed Gray. There’s an automatic window-closer that can be operated without leaving the bed, and an elaborate wake-up device complete with a mechanical hand that snatches the sheets and blankets off Gray’s bed, which rocks like a ship in a storm.

Gray also hates strangers using his outhouse: Buster boobytraps it with what appears to be a clothesline running from the outhouse to the kitchen. If an uninvited stranger enters the privy, Gray can yank the line and all four walls will open outwards and fall to the ground leaving the stranger visible, half undressed, seated on the toilet. Good old-fashioned comedy.

And eventually Buster discovers the camera. It happens very shortly after he abandons his father. When Buster hits twenty-one, he and the family decide they’ve had enough of Joe Keaton’s drinking. They ditch him in San Francisco and Buster heads for New York. It’s easy enough for him to find stage work there, but he gets an introduction to Fatty Arbuckle who convinces him he has a future in the movies. The fact that Joe pooh-poohed the movies as a passing fad is surely an encouragement.

Keaton has Arbuckle show him the camera. He sees how it works: the mechanics, the structure, the form, its range, its possibilities, its limitations. Keaton explores the inside of the camera as though he’s examining the anatomy of some exotic, alien creature. On set he befriends the cameraman, discusses trick photography with him. Buster investigates the lighting rig, visits the cutting room, the projection room. He understands it all, loves it. It’s all clear and comprehensible. It contains no mysteries beyond the ones he will create.

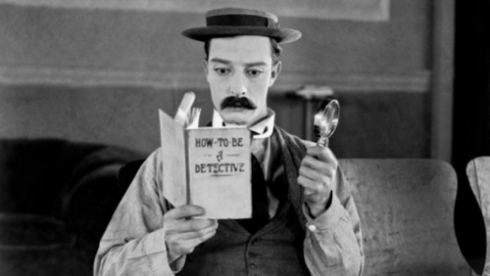

When I first came to live in Los Angeles, the Hollywood Entertainment Museum was in business, right there on Hollywood Boulevard, in a paved pedestrian area set back from the main drag. I visited, and it seemed interesting enough at the time, but afterwards the only thing I remembered was the bronze statue of Buster Keaton on display outside. It was a life-size piece by Emmanuil Snitkovsky, showing Keaton as he appears in The Cameraman, wearing a vest, bowtie, cap on backwards, complete with a freestanding movie camera, though it didn’t look much like the one he uses in the movie, which is an oblong wooden box, a crude home-made looking thing — that was the joke. Snitkovsky’s was an actual movie camera, which may have been a joke of a different kind.

In fact, when we very first see Keaton in The Cameraman, he isn’t a movie cameraman at all: he’s a street photographer offering to take tintypes of passersby. The camera he’s using is a gorgeous, antique thing, mocked by Buster’s rival as “that cocktail shaker;” which gets it about right. That’s what a certain kind of tintype camera looked like. It was that shape because it contained a developing tank, so the processing could be done there and then, a very early kind of instant photography.

The Hollywood Entertainment Museum closed down in 2007 — maybe it was set back too far off the main drag — and I did occasionally wonder what had happened to the Keaton statue. But it wasn’t much on my mind until I saw it come up for sale on an internet auction site. I’d missed the sale in December 2009, but the catalog remained online and it showed that the piece had gone unsold. The bidding had only got up to $600 before it was withdrawn. There was no indication of an estimate or reserve. My first, naïve thought was that maybe if I scraped together $650, I might have enough to secure the piece and have Buster and his camera in my own back yard. But of course I didn’t do anything about it.

The statue went up for auction again in January 2010 and this time the bidding went up to $2,500 though they still didn’t let it go at that price, and now the catalog revealed an estimate between twenty and forty thousand dollars. My extra fifty bucks wouldn’t have done the trick. Even so, it seemed a shame that the Keaton bronze hadn’t sold, was in limbo, unseen, presumably in a storage unit somewhere, rather than owned by somebody who’d appreciate and display it.

And then earlier this year I heard that the statue had been bought and relocated, and is now installed outside the Frauenthal Theatre in downtown Muskegon, in Michigan. You can be forgiven for not having heard of Muskegon. It’s a lakeside town, close to Bluffton where, in the early twentieth century, a group of vaudevillians had developed an Actors Colony, and where Buster’s father built a primitive summer cabin for the Keaton family. Buster said the best summers of his life were spent there. He played a lot of baseball. The good folks of Muskegon County came up with $22,000 to buy the statue: very much at the low end of the auction estimate, but rather more than I could have raised.

It is, of course, in The Cameraman that Keaton goes to Yankee Stadium to film a baseball game and finds the place eerily empty, since the Yankees are on the road, playing in St Louis. Undeterred he plays, or at least mimes, his own game. He has no bat, ball, or other players, and he has no need of them at that moment. Keaton’s skills make you “see” them all, as solid and real in the imagination as any object in the world.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!