Books in an Expanded Field: The Story of Badlands Unlimited

On Paul Chan, artist and founder of Badlands Unlimited publishing

By Matthew EricksonFebruary 8, 2013

I FIRST ENCOUNTERED the work of Paul Chan in 2006, when I happened to see one of his video installations in the cavernous former factory space of Mass MOCA in North Adams, Massachusetts. Chan’s piece, drawn with a deceptive crudeness and colored in bright hues, was a computer animation with the wonderful sinewy title Happiness (finally) after 35,000 Years of Civilization — after Henry Darger and Charles Fourier (2003). The video manages to transpose the characters and palette of Darger’s 15,145-page outsider-art magnum opus onto a scene that draws upon the ideas of the 19th century utopianist and philosopher Charles Fourier — somehow it coheres. Within Chan’s visionary world, Darger’s Vivian Girls embark on a series of strange adventures: they prance through fields of flowers, defecate on tables during a gluttonous banquet (pay attention during this scene and the viewer will hear a strangely baroque Casio version of Jay-Z’s song “Big Pimpin’”), graphically engage in every manner of orgiastic practice, endure war and torture, and finally, they enact revenge on their adult oppressors.

The piece ignited Chan’s career in the art world a decade ago. Since that time, he has embarked upon many projects that incorporate a wide span of aesthetic and political concerns. Baghdad in No Particular Order (2003), a wandering documentary in a similar vein as Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil, chronicles the time that Chan spent in sanction-crippled Iraq with the activist group Voices in the Wilderness. Another animated video installation, My Birds … trash … the future (2004), places Biggie Smalls and Pier Paolo Pasolini (murder victims, both) within a war-ravaged setting that is equal parts Leviticus, Goya, and Godot. As part of a group functioning under the umbrella name of The Friends of William Blake, in 2004 Chan helped design The People’s Guide to the Republican National Convention, which was released into the world as 25,000 foldable maps of New York City with information geared specifically towards visiting protestors (locating practical resources as well as the addresses of key RNC sponsors and war profiteers).

In 2007, Chan staged a series of acclaimed outdoor performances of Waiting for Godot in the devastated Lower Ninth Ward and Gentilly sections of post-Katrina New Orleans. The 7 Lights (2005–2007), Chan’s solo show at the New Museum in 2008, was centered around a series of floor-projected light installations that investigated Biblical accounts of the apocalypse by illustrating both levitating material-cultural detritus and 9/11’s falling bodies. And in 2009, he showed Sade for Sade’s Sake, an elaborate multidisciplinary take on Marquis de Sade’s The 120 Days of Sodom that had at its focal point a nearly six-hour projection of silhouetted figures entwined in a variety of sexual scenarios with ample amounts of perversion, humiliation, and domination.

But in his keynote address at the 2012 New York Art Book Fair, Chan claimed that after such a frenzied period of activity, he had decided to stop working. He’d declined fresh offers to exhibit and didn’t make new pieces. Citing other figures who have simply “stopped” as inspiration — workers going on strike, Marcel Duchamp (who famously quit the art world, though not art-making, at the height of his success to dedicate himself to chess), Yvonne Rainer (who decided to become a filmmaker after many years of groundbreaking work as a choreographer), and Samuel Beckett (who wrote Waiting for Godot as a something of a vacation from the grueling work of writing his great trilogy of novels) — Chan said he had wanted to begin something in an entirely different mode. This, it turns out, was his origin story for Badlands Unlimited, the publishing project he started in 2010.

¤

Chan’s press’ motto is, “We make books in an expanded field.” It’s both a nod to Rosalind Krauss’s landmark essay on sculpture and a statement of curatorial breadth. The past two years have seen Badlands publish titles in a wide variety of genres: the first English translation of Saddam Hussein’s early speeches on democracy accompanied by Chan’s fabric collages and charcoal portraits, a thin gem of collected poems from Yvonne Rainer, a translation of Plato’s Phaedrus via a series of invented “fonts” that alter the text’s original words into a string of shifting homoerotic found poems.

What’s perhaps most radical about Badlands Unlimited, though, is that Chan has decided to focus heavily on publishing ebooks, with paper books being somewhat secondary in the enterprise. While the notion of artist-as-publisher isn’t an entirely new concept, and the digital arts as we know them now are traceable to at least the 1960s, the idea of the artist-as-digital-publisher surely seems crass, if not sacrilegious, to many in the art world, where printed multiples and artist’s books can fetch absurdly high prices in a market that often favors the limited edition fetish object. The worlds of the ebook buyer and the art world spectator have not necessarily overlapped, until now.

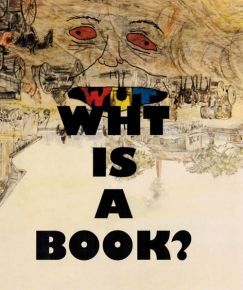

Of course, this kind of resistance to new technology has been repeated many times before. In his talk, Chan mentioned that during his non-work incubation period, he spent time researching the history of the book as a form. During the Renaissance, he noted, the printed book that Gutenberg was easing into the textual landscape was considered deeply untrustworthy in comparison to the handwritten manuscripts that were the most widespread way of transmitting words to a reader at the time. (For a fairly screwed take on this history, see Chan’s ebook Wht is a Book?) Is the current resistance to ebooks much different than that initial resistance to bound printed books, once suspect and now commonplace?

The possibilities of this relatively new medium are only one aspect of what makes Badlands such an interesting operation. As a publishing outfit, they are blurring the distinctions between art press, curatorial experiment and publishing industry gambit, while putting out a series of works that are strange enough individually, but seem even stranger when grouped together under the same moniker. This testifies not only to Chan’s diverse leanings as a reader (he coined it “reckless reading” in Calvin Tomkins’s 2008 New Yorker profile of him) but also his possible ambition to recategorize Badlands Unlimited more as a form of extended assemblage than a mere publishing project.

¤

Before deciding to take a look through the bulk of titles that Badlands has released over the past two years, I had never read an ebook. Plenty of skimming and browsing time is killed on a computer screen, but when it comes to reading, as in actually focusing on a text or image — as in doing more than mere glassy-eyed scrolling — the bound paper object is the ideal for me. Nevertheless, with an iPad borrowed from a friend, I set about exploring the newly expanded field that Badlands is charting in the digital realm.

The first thing I looked at was Waiting for Godot in New Orleans: A Field Guide, one of the earliest Badlands titles, which was released in both paper and e-forms. The book documents the thinking, planning, and inspirations leading up to the 2007 Beckett productions that Chan staged both on a desolate street intersection and in the front yard of an abandoned house in New Orleans within the close aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. The play — produced along with the public arts organization Creative Time, the Classical Theatre of Harlem and many New Orleans–based artists, activists, nonprofits, high schools and universities — was a hugely ambitious project and it is fascinating to see the different channels of preparation that led into it.

Much like The Essential and Incomplete Sade for Sade’s Sake — the first Badlands title and, essentially, an extended exhibition catalog for Chan’s show from 2009 — this book’s chief aim is to document the research and ephemera from the production. One difference is that Waiting for Godot in New Orleans features extensive amounts of writing alongside the visual documentation. There are theoretical essays on Beckett from Alain Badiou, Susan Sontag, and Terry Eagleton, as well as texts by Chan and many of the principle organizers, and interviews with a handful of New Orleans natives involved with realizing the play. There are numerous photographs of the rehearsals and community meetings leading up to the production, dozens of scans of lists, sketches, and posters.

Even though the content within this ebook doesn’t achieve much in terms of pushing the boundaries of the medium, it acts as a supplement to the other edition, adding elements that perhaps didn’t make the initial editorial cut for the print version. The ebook has some multimedia components — there are several audio clips lodged within the text at various points — but there seems to be a dynamism lacking in how it works within a digital layout. The book, regardless of its different medium, still reads like a book.

However, the other Badlands ebooks I was able to peruse did point to how the field of art book publishing could become expanded; each title underscored how the digital format could possibly fulfill different aesthetic purposes. It is through these later ebooks — messy, genreless, playful, and bizarre as they are — that Badlands is changing the nature of arts publishing. These titles, which are only available on ereaders, are experimental in the truest sense and could only work with the format at hand — either because their legibility wouldn’t necessarily translate to the kind of serial reading/viewing experience that a paper book provides or because the essentially unsellable perversity of ideas contained within the pages would make the financial risk too great.

Chan has noted that the economic aspect of publishing ebooks, the cheapness inherent to the production end of the medium, was one of the motivating factors for delving into the format. Within the context of operating a traditional publishing house, even on the level of a small press, thousands of dollars need to be funneled into production and distribution. With an ebook, the formatting is done digitally and then can be distributed as a download almost instantly, both at no real cost.

In many ways, the cheapness and immediacy of art ebooks echoes the early history of artists’ books. In 1914, when Vasily Kamensky’s letterpress printed his ferro-concrete poems on discarded floral wallpaper, it was certainly an aesthetic choice, but it was a gesture of intentional thrift as well, one that has been repeated numerous times within the history of artists’ books in the 20th century. Alongside the development of book arts as a craft, there has been the desire to use the form of the book as a cheaper mode of disseminating work that would otherwise be sold only at a gallery. Ed Ruscha’s conceptual book works from the early 1960s demonstrated that low-cost materials and common printing methods could be used to create large editions, without the whiff of rarity or exclusivity, for a wider general audience. This history could be extended on to include poetry mimeographs, punk zines, and a wide span of pre-Internet underground culture.

The Wht Is series that Chan made in the earlier stages of Badlands plays into this history. Each title ostensibly tackles a different quandary: Wht Is Nature?, Wht is a n Occupation?, Wht is Lawlessness?, Wht is a Berlusconi?, Wht is Wu Tang?, Wht is a Kardashian? But perhaps it goes without saying that none of the books really venture to answer any of these questions directly. Instead, each is a set of found book pages (textbooks, atlases, indexes) overprinted with text from various unattributed sources (Kant, Erica Jong), and screenshots of various Internet memes scattered throughout. The series straddles the split dilemma between art world rarity and wide, democratic distribution by having it both ways: each was originally made in an edition of one (sold in the $300 to $500 ballpark), with two artist proofs, but also made available as free scanned PDF downloads from the Badlands site. They are at once material and ultra-rare, digital and infinitely distributable. The books aren’t at all readable, as they are primarily dense tangles of overlaid words and images, and they aren’t necessarily groundbreaking aesthetic wonders to behold, but they’re excellent as a kind of art-market hoax: produced for next to nothing with found materials, then sold for a relatively high price, then reduced back to a freely available scale. In a similar tone, Badlands recently published a short story of Chan’s by engraving it onto a 3-foot-tall stone tablet, made legitimate with an actual ISBN number. It is available in an edition of one in the most material of possible forms or as an endlessly circulated two-page ebook.

Another aspect of digital publishing that Badlands seems to be emphasizing is the potential archival nature inherent to the medium. Take, for instance, the experimental Made in USA magazine from the collaborative Bernadette Corporation, which Badlands reissued last fall. One of the more recent role-models for the kind of contemporary art-publishing that Badlands is now doing, the Bernadette Corporation channeled their crossmedia work into a short-lived, three-issue magazine at the turn of the millennium. Merging the worlds of fashion and art, while slyly satirizing both, the magazine incorporated the design specs of a glossy rag with the feel of a Xeroxed zine. (The issue I looked at had writing from Chris Kraus and Stéphane Mallarmé, art from Jutta Koether and Rita Ackermann, a variety of interviews and essays, and many ads from fashion designers and galleries dispersed throughout.)

If you happened to be around the Lower East Side in the late 1990s, Made in USA was an influential, though highly ephemeral, periodical. If you weren’t there, you probably haven’t seen it. In reproducing these three issues, Badlands is permanently extending the publication’s life by making it widely available beyond its early origins. What was once hyperlocalized and rather limited has now become infinitely accessible. While it could be argued that some of the aura from the original is lost in the translation to digital, it’s probably preferable to the fate of Made in USA remaining only talked about or never discovered, for those who were outside of the sphere of the original moment. As with the Wht Is series, the translation of these works into ebooks is making what would otherwise have an air of precious scarcity into a endlessly reproduced work, both cheap to produce and cheap to purchase.

¤

The other three of the Badlands ebooks that I examined are playful with the potential of the e-format. They are experimental in that they seem to genuinely be figuring out how to work with the continuity and repetition of the pages, the design and layout of spreads and the amount of logical sense that is supposedly needed within the container of a book.

Mans in the Mirror, like a large portion of the Badlands catalog, resides in the world of trickster surrealism. Supposedly created while under the effects of mescaline, it was intended as something of an homage to the book Miserable Miracle by the poet and painter Henri Michaux, which was itself a chronicle of the writer’s transformed consciousness through the use of the same drug. This Badlands edition also claims to be the first-ever 3D ebook. (As I didn’t have any 3D glasses at my disposal, I couldn’t verify the claim.) If this is what the merging of digital art and hallucinogenics looks like, it appears as a glowing psychedelic nightmare. X-ray tinged naked bodies, scribbled line drawings, calligraphic drawings in the style of Michaux, and chopped portraits are all blurred in the familiar stereoscopic blues and reds of 3D visuals.

Rachel Harrison’s The Help, A Companion Guide is an auxiliary, behind-the-scenes take on her 2012 solo show of sculptures at the Greene Naftali Gallery in New York. The work takes its title from the visible maintenance entrance to Marcel Ducahmp’s final, room-sized installation Étant donnés. Similarly, within this ebook, Harrison is dealing with the art handlers and gallery workers that assisted in setting up the exhibition of her work, people that are usually ignored and underacknowledged. The ebook consists of screenshot Google searches on Picasso, drawings of Amy Winehouse, and detailed photographic spreads of her sculptures being moved, unpacked, assembled, shifted, cleaned, and prepared. What is the thread connecting Picasso, Winehouse, and art handlers? Perhaps only Harrison herself knows. The Help reads both as a quickly assembled scrapbook documenting the long process of Harrison’s work reaching the public, as well as a window into an artist’s mind outside of her studio. Like some of the other Badlands ebooks, it is doubtful that it would be published in any other form, but as a one-off record it’s an appealing experiment.

Having the special distinction of being the first ebook to be reviewed in the pages of Artforum, Net artist Petra Cortright’s HELL_TREE is possibly the strangest book in a catalog that is replete with strangeness. Unlike any of the other Badlands books, physical or digital, HELL_TREE may not even be easily categorized as a book, at least as we are familiar with the form. Gone are page breaks, pictorial spreads, and any real sense of recto and verso. In their place is a jumbled mesh of schizophrenic desktop detritus. A sculptor or painter’s studio is fairly easy to imagine for most people, but what does an Internet artist’s studio look like? It would be HELL_TREE.

If it’s possible to show simultaneous events on a page, this might be the finest example. As a layered series of screenshots throughout the span of a few days, spread across each turn of the e-page, Cortright’s desktop is a garble of notes to herself, to-do-lists, project ideas, emoticons, half-way poetry, diary entries, unfinished emails, assorted images grabbed from the corners of the Internet, random words strung together and letters strung into nonwords. It’s complete chaos. Yet, it truly does have the effect of being a snapshot of a working artist’s studio at a given moment. Are we looking at works in progress or are these the works themselves, already where they are intended to be? How can this book be evaluated? Is it readable? Is it beautiful? Is it good, by any measure? I would venture that most people might resoundingly answer “No” to each question. Nobody can deny, though, that it is unlike any other artist’s book in existence. As Bruce Sterling wrote in his Artforum review: “Reading the book is like finding a lost, sticker-covered iPad, whose owner left its screen bewitched with hairy stains from her fur-lined Meret Oppenheim coffee cup.”

The last of the Badlands books that I wanted to check out was the anthology How to Download a Boyfriend, which is being touted as the first group exhibition to take the form of an interactive ebook. It has the work of 50 artists, as well as a series of quizzes that promise to “test readers with funny, probing, or simply absurd questions about love and longing in the 21st century.” I was looking forward to taking it all in. Yet every time that I would click on the link that should have let me purchase the book on iTunes, a window popped up: “Your request could not be completed. The item you’ve requested is not currently available in the U.S. store.” After some light investigating, I found out that Apple had some issues with the content, apparently concerning nudity in the book, and temporarily retracted it from their stock.

Could this point to a kink in the limitless potential of ebooks, for artists or otherwise? It seems as though having the distribution concentrated through the channels of only a few powerful companies could be seriously problematic to the longevity of the medium. The fact that anything not suiting Apple’s chaste whims could be eliminated from their stock is a form of censorship that is never really seen in small-presses within the physical realm. However, on the other side of this coin, Hurricane Sandy recently destroyed large portions of artworks and art books in New York City. Included in this were many great entities like the nonprofit Printed Matter that lost around 9,000 books from water damage, as well as the publisher Primary Information and other outlets for first-rate artists’ books and works-on-paper multiples, their stocks thoroughly flooded and soaked through. Perhaps this points to the need for both ends of the spectrum: the physical for a design to hold in hand when the electrical grid fails as well as the digital, for the archival preservation of works that can weather the rising tides.

¤

LARB Contributor

Matthew Erickson currently lives in Saint Louis. His writing has appeared in Parkett, The Wire, Arthur, Gladtree Journal, and a few other places.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Image of Genre

Reading an artist's novel is often a kind of aesthetic or intellectual work rather than a leisure activity.

Agreeable Objects: On Ken Price

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!