Blood Positive: Recovering Poetry from the AIDS crisis

A handful of poets faced with death sat in a circle. Their poems share the threads, murmurs, and syntax of two crises: the urban crisis and the AIDS crisis.

By Sean SingerSeptember 19, 2013

worlds that flare / and consume so they become the only world.

– Lynda Hull

there is no life but this / and history will not be kind.

– Melvin Dixon

The history of the frame reframes itself as the history of the failure to reframe.

– Tory Dent

Prologue: Recovery

A HANDFUL OF POETS FACED WITH DEATH sat in a circle. Their poems share the threads, murmurs, and syntax of two crises: the urban crisis and the AIDS crisis. These crises occurred simultaneously, during the 1980s and ’90s, and, in the cultural imagination, they were associated with the same groups of people — Haitians, homosexuals, and heroin addicts, for example. Both crises were also exacerbated by municipal and political structures that chose to ignore them, doing little or nothing to address their sources. Just as people in urban centers were often seen as being responsible for the decay, arson, and drug abuse consuming their blocks, victims of AIDS were seen as similarly responsible for their sickness because of their sexual or social behavior. Poetry from the era can help us understand much about the urban crisis and the AIDS crisis, because poetry often became an avenue of recovery from this decay. Let’s recover this poetry, put it in its proper context, and understand the acts of recovery the poets underwent by writing these poems.

What can we learn about the ways AIDS and cities were connected by reading the poems produced at the time? What can we learn about the impact that AIDS has had on the evolution of poetry, art, and culture in America? And what can we learn about the ways in which memory can aid recovery, both on a personal and a societal level?

The best poems from the period document both the personal deterioration and the public deterioration that occurred. They investigate the crisis with an intense and empathetic artistic inquiry that asks: what else have you got to say about reading this city and this disease with love? The Whitmanesque assemblages of city life pulse and thrum through the language of the poems, even as the inevitable burning-down of that life casts pathos on everyday objects. Poems from the AIDS crisis teach us that loss engages with memory: all losses trigger all previous losses. So, a poet’s private memory is a window into the public memory of the event: its grief, its mores, and its metaphors.

Some of the poetry from this period has not lasted. It was elegiac, abstract, sentimental, or flat; it lacked a rigor in terms of language and did not offer fresh insights into the horrors the poets sought to address. Most of the poems written during the AIDS crisis turned out to be elegies — the expected form to address overwhelming grief. Many of these were unsuccessful because they fell into familiar tropes bound up with the form. David Groff, who won the National Poetry Series in 2002 for his collection Theory of Devolution and coauthored The Crisis of Desire: AIDS and the Gay Brotherhood, explains why he often found the elegy to be an inadequate or problematic response to AIDS:

There were all these reactions from straight people of being kind of bummed and kind of defaulting to an elegy and an absence of specifics of AIDS that denied injustice I felt. A lot poems, especially by straight people, that said AIDS is a bummer and how it was symptomatic of how death can happen and life is unfair. That seemed to me almost a kind of glib reaction, to take AIDS as almost too-easy a metaphor of mortality, when in fact, AIDS in life and in literature is this hugely wrought conflation of every issue of love and death, but also social justice and unfairness, political powerlessness, race, culture, and sexuality. It is one of the grand and awful metaphors of our time and I think you have to approach that with fear and trembling as a poet or any kind of writer […] Elegy is not just grief and grief is not just sadness. There was something more powerful to address there. It was much more of a complex garden to explore and shape in literature.

The crisis was so complex, it is only natural that many of the attempts fell short. This makes the successes even greater achievements. Some poets created their best work in spite of the looming pressures of a disease that was killing them, or the people they loved. I’ve chosen works by four exemplary poets — Charles Barber, Melvin Dixon, Tory Dent, and Lynda Hull — that transcend the expectations of a traditional elegy, pushing the form into new realms of expression, or working against the form, in order to create profound emotional and political responses.

Poetic responses to the urban/AIDS crisis are inherently political responses, because they demand consideration of issues that the politicians of the era largely ignored. The common reaction was to retreat. By claiming the crisis was intractable, commentators severed their moral ties to people and places in decline and reneged on their social obligations. The practical advice became extreme — abandon the city and the people who live there! Poetry serves as a corrective to the cynicism, the hackneyed speech, and the dead language of politics because it constantly refreshes and engages language so that it demands to be heard and considered. The reader’s ethical and imaginative sensibilities are stimulated by the mechanisms of a poem.

Douglas Crimp, an art historian and activist, says:

[V]iolence of silence and omission is almost as impossible to endure as violence of unleashed hatred and outright murder. Because this violence also desecrates the memories of our dead, we rise in anger to vindicate them. For many of us, mourning became militancy.

The following works by Barber, Dixon, Dent, and Hull offer a correction to the violence of silence, a recovery from personal and public losses. These poets were aware of the injustice of silent mourning or absent language, and their language constitutes a militant reaction.

Tension, like a rope being pulled from both ends, infuses the best of poems. In the following four works, the forces pulling on the poets as they wrote were extreme. When we read them, we can see how the desire for a peaceful domestic life — an escape from the decay of the city — constantly wrangles with the love of the city’s vitality. This mirrors the way that the desire to escape the suffering of disease wrangles with the inexorable pulling away from death. The tensions pull these poets into fresh territory, where they are unbound in their treatment of language, of syntax, and of space (both the space on the page and the physical space of the city). Groff said of Tory Dent, for example, “Her poems all were written because time was short.” Poems like these teach us that language is vital, if not essential.

1. Charles Barber’s Dream

In Charles Barber’s poem “Lapel Button,” a seemingly unimportant sartorial decoration takes on more momentous proportions. The lapel button is the fulcrum between a private memory of the speaker’s own death and the public backdrop of an imposing building, the essential element of any city. The poem opens with a typical urban scene:

A hot summer day.

I have slept too long,

once again,

and the air-conditioner

hanging over West 16th Street

streams.

This stanza connects a private moment with public space, locating the person within the city, and it ends with “streams” on its own line, an allusion to the pastoral mode. The second stanza addresses what Langdon Hammer refers to as the “instability of the relation between culture and AIDS […] the feeling that high art is alternately remote from the catastrophe ‘AIDS’ names and deeply implicated in it”:

I’d been watching a Callas video

of Alfred’s,

to study the singer’s clasped arms,

the constant dialogue

between actor and acted;

as Gordon once told me,

the sign of greatness

in a performer.

Hers is a private moment

that I am privileged to share;

“Let me reveal,”

says her pain,

“not only the thought,

but the thinker.”

Somehow,

in this big stupid opera,

out of the darkness

of the wings,

and from behind the badly painted scenery

and fifties hair-do’s,

there’s suddenly a fusion

of sadness and knowledge.

The speaker experiences watching the video of renowned soprano Maria Callas through two intermediaries: Alfred, who owns the video, and Gordon, who describes the thin brocade between actor and act. This division between performer and performance, which exists not only on a stage, but also in personal relationships, is the metaphor at stake here. If the speaker must keep performing in the midst of suffering until the tragedy reaches its inevitable conclusion in death, then “the constant dialogue” represents his only refuge. More than just a symbol of the statement vita brevis ars longa, Callas acts as the link between the speaker’s private pain and a shared human anxiety.

Callas played the title role in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Medea (1969), a destructive character who endures the shame of the victim. She acts as the double for the speaker in the poem, who shares her “private moment.” Just as opera demands an outpouring of endurance and wonderment from the performer in a dramatic public display, the speaker confronts the disease eating at him from within as a communal spectacle:

Sleep…

Waking…

Confused by the all-white walls,

so like the ocean:

empty but everywhere.

I pull on my shorts,

shoes, my favorite plaid shirt

with the ripped shoulder from when

Laurent pulled it off David too fast,

stripping down in Paris.

The “all-white walls” have the feeling of a sanitized zone, the hospital, as well as the classical formality of the dream space, which is the source of the speaker’s confusion. He has a memento mori from David, whose public disrobing is at odds with the more private intimacy of the speaker getting dressed in another’s clothes:

In a flash of the elevator

I’m on Fifth Avenue,

long-legged, tan from the beach

striding over poodles

and quite lost in self-love

and coffee smells.

Only my sneakers

on the pavement

hold me down.

The setting sun means:

ballet class, seltzer, endless time;

all of downtown

to be discovered,

the sun

pinned to my lapel

a pink and orange

button of continuance.

The title refers not to the red ribbon some people wear to increase awareness of HIV/AIDS, but to the sun and to “continuance,” which is essentially the same thing as the red ribbon. The red ribbon is a symbol that suggests life, the continuation of life. The tone and lineation of these lines is much like Frank O’Hara’s lunch poems. Like O’Hara, Barber mixes realism and surrealism, literal and fanciful elements of his language, to make a link between his own persona and the city landscape:

Three years later,

and winter, oh boy

is it ever.

Adam and I eat Indian food

while he quizzes me

on my feelings for him,

which are less than they might be

if he was another someone.

We watch Rock Hudson

dying on T.V.

The actor playing

the actor

is not good, does not know

how to die.

Or at least, I wouldn’t do it

that way;

he’s not nearly tired enough;

his eyes are lively

the way they wouldn’t be;

he blinks,

which requires too much strength

at this point;

his hair is tidy

and there is nothing caked on his face

except pancake;

he isn’t gaunt enough; the bones

have not emerged thoughtfully

as they do when

knowledge

meets sadness

and it’s just too late

in the afternoon.

The short lines give the poem a rapid pace, which increases the shock to the reader as the speaker travels from the womb-like summer morning to the wintry, tomb-like coda. The poem has quickly advanced in time as the psychic distance shrinks: the speaker reveals his own confrontation — displaced through television — with death. The interjection “it’s just too late in the afternoon” obviously occurs in the foreground (the speaker’s own afternoon), and not in the background (the actor playing the actor).

Later the speaker says, “Still, I can dream my own death”; like Medea’s prophetic burning of Jason’s children, the encounter with the actor opens the imaginative leap for him to die in a fantasy. The poem ends with this phantasmagoria:

It’s one of those cast-iron buildings

in the teens,

recently renovated,

sure of purpose

with dirty windows

and messengers rushing in and out.

Is it my building, though?

I unfurl the Post-It

clutched in my fist.

It is.

I’m so tired

I can barely carry my luggage

(brought enough for a long stay!)

up to the revolving door.

The doorman

does not help,

but frowns at me.

In a whoosh of glass

and breath

I am in the door,

refracted and blurry,

spinning, spinning.

The strength of the guy behind me,

in an even greater hurry

to gain entrance,

slams the bottom of the door

into my heels.

Then the marbleized lobby,

the office-like hush.

As he enters the building’s revolving door, uncertain if he is in his own building, someone stronger forces the door into his heels. The somewhat de-centering, surprising image of the “office” has connotations not only of “place of work,” but also of “responsibility.” Even in a dream, the speaker is responsible for continuing his own life (e.g. “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities” by Delmore Schwartz). The marble lobby, too, suggests the speaker has entered his own mausoleum, as the stronger presence behind him shoves him along the vestibule. Besides this poem’s obvious metaphors regarding inevitable death, the poem is also about pleading with the exactitude and monotony of a workaday life.

2. Melvin Dixon’s Bodies

“Spring Cleaning” by Melvin Dixon is a poem that overturns our expectations of the joyful boredom of a marriage, of domesticity, of chores, and of cleansing. In cleaning house, and getting rid of old things, the speaker performs a necessary ritual; the couple feels the oblivion of chaos when things are not cleaned:

First goes floordust, then newspapers

stacked near the bed. Peanut shells

swept out of hiding between mattress

and rug. Toenails clipped.

Sprouts of a beard shaved off.

With hourly glasses of Deer Park Water

and the barest of food, the body

sheds winter fat and filler.

The hair goes next, close

to the gleaming, gleaming skull.

You are ready for the sun

and the salt-tongued air.

You are someone new. I will be

someone new, like you, and promise

not to hear the rattle our bones make

moving from empty closets

and all through the room.

Dixon evokes the haunting nature of domestic life between two lovers despite the illness killing them. As AIDS activist Simon Watney has observed, “the instant association of AIDS with death — death from AIDS — rather than consideration of the problem of living with AIDS” dominates thinking about the disease. Dixon tears down this association; metaphors of materiality giving way to less (shells, nails, hair, etc.) are linked with the large, corporate-sized cooler of water. Like a hibernating animal in reverse, this couple instead is losing weight. The pathos of “salt-tongued air” suggests another absence — that of sexual contact, which forces the tongues to taste salty, empty space. Ironically, despite the looming mortality above them, the third stanza is an affirmation of their ability to transform themselves through love, even as they become aware their skeletons will inhabit the same rooms where they once lived. The poem’s form, in three-stanza structure, mirrors the story-like, episodic nature both of illness and of the domestic parts of married life.

Dixon was as much grappling with life as with death, yet it remains impossible not to read “Spring Cleaning” through the lens of death. Though its sentiment on one level is elegiac, the poem upends the limitations of an elegy and creates a powerful testament to the struggle to maintain normalcy, through the tedium of cleaning, and to maintain life. The verbs “be” and “promise” reaffirm the joint connection symbolized by a marriage; the bones moving from the empty closets imply a haze cast upon their homosexuality, since their “coming out” from them was a public manifestation of both their romantic life and the disease that would kill them. (Ironically, Dixon wrote all the poems in Poets for Life before he knew he was HIV-positive, including the profound “Heartbeats,” another poem in which formal beauty mirrors content.)

Another way “Spring Cleaning” adduces its meaning is by a kind of listing: the inorganic particles (floordust, newspapers) give way to the organic (peanut shells, toenails), but all items pile up in an apartment that is simultaneously being filled and being emptied. Though “the body / sheds winter fat and filler,” it is ironically a promise of absence (e.g. “not to hear the rattle”) and empty closets that becomes the heaviest, most resounding presence for the person. That the poem ends with the word “room” hints that the outside space will finally triumph over that of the interior. Donald Justice engages a similar trope in the beautiful short lyric “A Map of Love”:

Your face more than others' faces

Maps the half-remembered places

I have come to while I slept—

Continents a dream had kept

Secret from all waking folk

Till to your face I awoke,

And remembered then the shore,

And the dark interior.

In both poems, a minor chord is struck (note the slant rhymes: room / new; shore / interior) to indicate the rift between what happens within the person and what occurs in the exterior (the room). Langdon Hammer sees a related trend in the elegies for David Kalstone by Rich and Merrill: “the dead and living recognize each other — or recognize themselves in each other — with a feeling of complicity I want to call love.” Elegies like Dixon’s and Merrill’s can achieve this complicity — but can “Spring Cleaning” even be considered an elegy? The speaker doesn’t appear until the third stanza, and the bodies are practically nonspecific. In this sense, it is an anti-lyric.

3. Tory Dent’s Cinematography

While “Spring Cleaning” uses compression, and a tender, haunting tone to break open the elegy, the works of both Tory Dent and Lynda Hull use styles that are expansive and incantatory. Theirs is a rage-filled alternative to the AIDS elegy that seeks to speak to the inexpressible netherworld of private suffering and public understanding (or misunderstanding), which is history. The long-form and long-lines of these poets use tone to connect disparate strains of information, and they paradoxically condense their rage at social injustice in style overflowing with zeal, disgust, and terror.

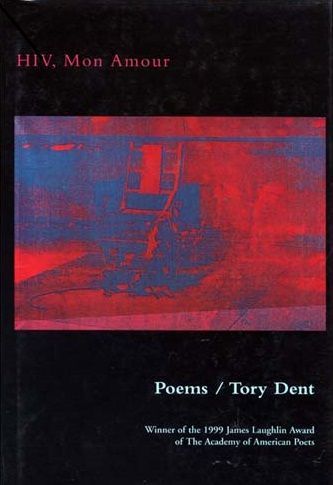

Groff sees these attempts against elegy as having “a radical sense of injustice not just about the body, but the body politic. Things were too urgent and vital in getting out there; [they were] not about to use strategies of indirection.” In Tory Dent’s long-form masterpieces “Cinéma Vérité,” “HIV, Mon Amour,” and “Black Milk,” the texture, size, and inclusiveness are a product of the ephemeral situation the poets were facing. Dent didn’t have time to be concise, and her political and social outrage, her bravery and dread, precluded the creation of smaller poems. “Cinéma Vérité,” for example, ends with the line “There is no good last line for this poem.” These confrontational, explosive poems work to connect a private suffering, though immense, with a shared notion of public memory and public witness.

“Cinéma Vérité” begins with the inside body merging with external space in a surprising way:

Like great moments in filmmaking when Brando adheres his wad

of ACG (already chewed gum) under the iron balcony and parodies

the decline of late twentieth-century Europe with this gesture.

Besides its play with both contempt and reverence, this stanza introduces many of the ideas upon which the poem expands: the sexual (his wad), cultural (Brando, Europe), and persona, who exists in the omniscient first-person singular.

Like Barber’s assertion of himself through the actor playing Rock Hudson, Dent uses a similar metaphor in the fourth stanza:

According to a sadist’s definition of “slowly”

as in torture, as in interrogation, where the voice of confession

becomes the belated product, a fetish accoutrement, of its oppressor

the libido frees itself like a holocaust survivor

and the world, poor and empty as the final frame in The Passenger

where the clay terrain, the barking dog, the shrunken sky

become merely the fetishistic accoutrements of poverty and emptiness.

I see my future through the eyes of that Jack Nicholson.

Dent uses the style-less academic voice (“fetishistic accoutrements”) but increases its outrage and scope to become a Medea-like whirlwind. The reader gradually becomes aware, as the poem teaches us how to read it, that Dent is addressing not only culture’s inability to encompass AIDS, but also the ex-lover who infected her:

Today is the anniversary of when we last saw each other. Turning the corner

your face lit up like Northumberland terrain idealized by a Northumbrian.

But the earth and its oral traditions now serve only to disappoint me

as do my friends, as does UPS, as does the road, winding or freeway,

in light of the Jacobean erasure of that expression; the snapshot I’ll not have.

We stood where the clouds colluded in a tenet of unsurpassed fatalism

flattering to our star-crossed desires as the dream of duet suicide.

We experienced our corporeality fail us then, conversely, in the pleasure

of touching, for we are not, like sanitized forceps, touching now.

We are not, like forsythia and lake water, touching now.

Corporeality failed us both even though only one of us died.

Taking the initial image of the gum to extremes of raw honesty and uncomfortable exhibitionism, Dent evokes the menace of AIDS-specific death: “like a lock of your hair where a kind of double death occurs upon discovery, / the way masturbating to the memory of a dead man becomes the only way to climax”; “I breathe in deeply the sickly air of a city plagued by an august siesta”; “We wanted to regard, feckless / and arrogant, our lovelorn bodies hang like laundry, like Kiki Smith’s, like / El Salvadorian civilians from a barn fence, putrid as dung in the torched meadow”; and this bizarre and stunning connection between sexual desire and inevitable destruction:

And the silence enswathes us like weather, like fluid, viscous as fetal fluid,

carnal like the electric currents between two replicants fucking in Blade Runner,

or a Jewish couple on the train to their death camp who fornicate before strangers

on metal and straw, damp with urine and menstrual blood, and fresh feces.

Your great hands mash the filth into my hair as if into my brain when you come.

Unlike Plath’s frequent, and I think inappropriate, use of Holocaust-related imagery to exorcise her own private pain, Dent here evokes a rage beyond invective mode to shatter even metaphor, which cannot last long enough to say what she requires in the time she has. She kneads the death image to its surprising, funny, self-deprecating conclusions:

My use for it damaged irreversibly by your death in that your death has replaced it.

I never saw you die so before me I envision you continually dying

a solider shot in the leg wiggling like an agama amid the frontline grasses

a teenager who drowns himself in the local lake at midnight

beneath a serene constellation. Taurus.

His acute longing disguised as a death wish sits inside me, just waiting.

What should be ameliorated only gets worse. O tell me, is death more even?

Of any poem written in response to AIDS, perhaps Dent’s is the most encompassing in terms of its style, technique, expressiveness, and size. Despite the long lines and long length, the poem is effortlessly controlled: it is sustained. Energy is difficult to maintain in a poem, especially in long-form work. Without using terza rima or blank verse, Dent offers a knotted, textured tone that connects everything: cinema, art, death, history, her own tragedy.

The interior consciousness overwhelms everything. Unlike Dixon’s poem, in which the person becomes invisible, or Barber’s, in which the person is sublimated within a dream, Dent’s poem places the despairing speaker front and center.

4. Lynda Hull’s Fugitive Moments

Lynda Hull’s “Suite for Emily” has a similar tone and focus as Dent’s poem, though Hull’s poem is entirely directed outward. It is directed toward Emily’s experience rather than her own. In this sprawling work, divided into seven sections, Hull’s speaker serves as the messenger for Emily, the medium for the despair that AIDS produces. The poem connects a heroin-addicted friend’s death from AIDS (“I didn’t know // how sick I was — if the heroin wanted the AIDS, / or if the disease wanted the heroin”) with the affliction Hull sees in Emily Dickinson’s poems (“the Hour of Lead — / Remembered, if outlived, / As Freezing persons, recollect the Snow — / First Chill — then Stupor — then the letting go”). This poem, too, links a somewhat purple, though bleak, urban landscape with that of Emily’s death:

I can map it

in my mind, some parallel world, the ghost city

beneath the city. Parallel lives, the ones

I didn’t choose, the one that kept her.

In all that dangerous cobalt luster

where was safety? Home? When we were delirium

on rooftops, the sudden thrill of wind dervishing

cellophane, the shredded cigarettes. We were

the dust the Haitians spit on to commemorate

the dead, the click & slurried fall of beads

across a doorway

Hull investigates the displacement those infected must have felt in a city that had seemingly rejected them. She also uses rhetorical questions that force the reader to reveal his or her feelings without necessarily revealing her own.

Later, in the fourth section, “Jail, Flames — Jersey, 1971,” Hull dramatically connects Emily’s private pain with the physical city:

Everything you ever meant to be, pfft,

out the window in sulphured matchlight, slow tinder

& strike, possession purely ardent as worship

& the scream working its way out

of your bones, demolition of wall & strut

within until you’re stark animal need. That is

love, isn’t it? Everything you meant to be falls

away so you dwell within a perfect

singularity, a kind of saint

The walls & struts are "within" — not only within the jail, but also within the jail of the body. The word "within" does much work here to link the city and the body, until the speaker is reduced to "stark animal need." Hull empathically links anger toward the virus, her own incapacity to do anything to save Emily, and the formal requirements not only of the city, but also of the suffering itself.

The empathic person speaking in Hull’s poems looks forward with a sense of artistic and political freedom. Imagination is the connection-making aspect of human intelligence, and Hull’s allows for multiple, conflicting emotions to coexist. She describes even the emotions we feel unconsciously, while preventing erasure of those fresh sense impressions. Her poems last as beautiful objets d’art, but more than that, they decrease normalized indifference and state her values, her general affection for cities. We should care about Lynda Hull because she wards off not only outside messages of defeat, but also those that can sometimes creep into our own minds.

The next section, an address to Death, is pyrotechnical in its facility with language; the second-person pronoun is the grim reaper:

I’ve seen you slow-dance in a velvet mask, dip

& swirl across a dissolving parquet.

I’ve seen you swing open the iron gate —

A garden spired in a valerian, skullcap, blue vervain.

Seen you stir in the neat half-moons, fingernails

left absently in a glazed dish.

Felons, I’ve cursed you in your greed, have spat

& wept then acquiesced in your wake. Without rue

or pity, you have marked the lintels & blackened

the water. Your guises multiply, bewildering

as the firmament’s careless jewelry.

Much of Hull’s work operates along a trajectory of her memory of urban spaces. The private sectors of her past become inextricably bound to the public knowledge of cities. Her poems are the guide through her own memory, even as the tour expands into a collective retrieval for the cities slowly succumbing. Memory is place-oriented. To this end, “Suite for Emily” concludes by deliberately connecting the speaker’s (Hull’s?) memory of Emily to the city itself:

But oh, let Emily become anything

but the harp she is, too human, to shiver

grievous such wracked & torn discord. Let her be

the foam driven before the wind over the lakes,

over the seas, the powdery glow floating

the street with evening — saffron, rose, sienna

bricks, matte gold, to be the good steam

clanking pipes, that warm music glazing the panes,

each fugitive moment the heaven we choose to make.

Here, the connection between the suffering from AIDS and the suffering of living in a decrepit city seem to have the overdetermined quality of beauty (saffron, rose, sienna, etc.) attached to it. The affected exclamation “oh,” invoking a kind of Greek chorus, and the metaphor of the harp form a delicate balance with the pain evoked in the poem heretofore. The poem ends, too, during winter — the steam pipes, the glazing the panes (with the pun on “pain”) — and leads inevitably to the powerful, vivid last line.

Epilogue: Recovery

Charles Barber, Melvin Dixon, Tory Dent, and Lynda Hull, though diverse in their relationships to AIDS (Dent was heterosexual, Dixon and Barber were homosexual; Dixon was black, and Barber was white; Hull was an outsider, an empathetic witness), were unique in the ways their poetries both encompassed and worked against death. Apotheosis of subject and form in these cases may seem extreme, if not counterintuitive, yet they push through the elegy with wildly passionate syntax, attention to detail, and localized grief. In the Aristotelian sense of catharsis, these poets sought to heal themselves. Their language was a process as well as a product that was part of a path toward healing. This process was not only a personal recovery from destruction, but also a public recovery of language, enlivening it and pushing it to new limits in order to combat silence, because silence equals death.

AIDS is now thought of, at least in the West, as a chronic disease, and not as a crisis. Through anti-elegiac poems, the portrait-like gems of Barber and Dixon, or the wild horizontal and vertical movement of Dent and Hull, these poems can reintroduce the urgency of epidemic into the literary imagination. One of William Stafford’s maxims was: “Language can do what it can’t say.” These poems break down the ways historical memory has made the AIDS crisis an abstraction. They show the strengths of using art to recover standard ways of telling the story of the AIDS crisis.

Poems written during the AIDS crisis can also sharpen what illness means because the reader uses her breath and body in the present to connect to the poets’ mind in the past. The poem, then, is the bridge between health and sickness, two points in time, the memory and its embodiment. The poem recovers the memory of its authors. Charles Barber and Melvin Dixon died of AIDS in 1992. Lynda Hull died in a car crash in 1994. Tory Dent died of AIDS in 2005. When I read Barber, Dixon, Dent, and Hull, they do not seem dead, though they aren’t present.

¤

Sean Singer has a Ph.D. in American Studies from Rutgers-Newark.

LARB Contributor

Sean Singer's first book Discography won the 2001 Yale Series of Younger Poets Prize, selected by W.S. Merwin, and the Norma Farber First Book Award from the Poetry Society of America. He has also published two chapbooks, Passport and Keep Right On Playing Through the Mirror Over the Water, both with Beard of Bees Press and is the recipient of a Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. He has his Ph.D. in American Studies from Rutgers-Newark.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The More Noise, the More They Listen

Larry Kramer may be getting older, but his passion, anger, and humor about AIDS is only getting stronger, in his activism, his writings, and his life.

Capsid: A Love Song

How to live and love with AIDS.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!