Big Cheese: Michael Paterniti's "The Telling Room"

Michael Paterniti falls in love with a cheese, or rather with the idea of this cheese, because he goes for years without tasting the creamy insides of his beloved queso.

By Mark Haskell SmithSeptember 13, 2013

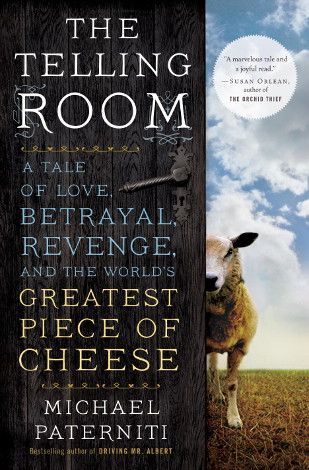

The Telling Room by Michael Paterniti. 368 pages.

I HAVE NEVER FALLEN IN LOVE with a cheese. Don’t get me wrong, I am not lactose intolerant. I am not only totally tolerant of lactose, but I am very fond of coagulated milk protein, particularly when aged and made from goat or sheep milk. I like cheese a lot. We’ve had some good times together, and I hope we can continue to be friends.

Author Michael Paterniti is not so coy about his feelings toward cheese. Especially when a little Spanish cheese sitting in Zingerman’s Deli in Ann Arbor turns his head. In fact, like a knight who hears tell of a beautiful, virtuous princess, Paterniti develops feelings for this cheese merely by hearing it described.

In his new book The Telling Room: A Tale of Love, Betrayal, Revenge, and the World’s Greatest Piece of Cheese, Paterniti recounts his more than 20-year love affair with this cheese, or perhaps more accurately, with the idea of this cheese, because he goes for years without tasting the creamy insides of his beloved queso — his love remains as virginal and pure as the olive oil the cheese was packed in.

His story begins in the early 1990s. Just graduated from a creative writing program, Paterniti submits to magazines stories that he “typed in fits of Kerouacian ecstacy,” stories that are returned “like homing pigeons” in their own self-addressed envelopes. Looking for some income, he takes a job editing Zingerman’s newsletter, written by deli co-owner and globetrotting gourmand Ari Weinzweig. After discovering a “sublime” cheese in London, Weinzweig travels to a Castilian village to visit its maker. It became the most expensive cheese Zingerman’s had ever carried. Struck by a joy so strong it improved Weinzwig’s usually plebeian prose style, Paterniti comes to the deli case merely to gaze at the cheese, made from an ancient family recipe. At $22 a pound, he can’t afford it, or maybe he worries he does not deserve this cheese. “It seemed to hover there, apart in its own mystical world.” Enchanted, Paterniti “senses the presence of purity and transcendence.”

Years pass from his first meeting with the cheese, but, like all true loves, it’s never far from his mind, and when Paterniti is finally offered a chance to go to Spain — ironically to write about El Bulli, at the time considered the world’s best restaurant and a laboratory for molecular gastronomy — he uses the opportunity to track down the author of this mysterious cheese.

Paterniti and a friend/interpreter arrive in a tiny town in the countryside north of Madrid where they meet Ambrosio Molinos de la Hera, farmer, cheese-maker, and larger-than-life poster boy for the slow food movement. Ambrosio invites them into his bodega, or “telling room” — a literal man cave carved into the side of a hill — and proceeds to inform them that all the world’s problems stem from the fact that “no one knows how to shit anymore.”

From this point, early in the book, the story splits off into parallel narratives. In one Paterniti tells the story of Ambrosio and his cheese — how this exceptional milk product was made with love and care to evoke memories of an older, simpler time, how the cheese became celebrated and enjoyed by European royalty and cheese connoisseurs around the world, and how Ambrosio was ultimately betrayed by his best friend and had the cheese stolen from him. It is a complex, operatic tale filled with emotion. There is friendship and love, success betrayal and failure, the rich history of Castile, and hundreds of digressions that cover everything from Spanish Civil War death squads to a man who miraculously takes flight and is guided by the wind to find his grandfather’s grave. This is a town in which stories and cheese run deep, a town whose values are personified in the aptly named Ambrosio.

Paterniti’s other narrative is a quasi-memoir as the author searches for meaning in his hectic American life and struggles with the realities of trying to write a book he’s not sure he can write. He’s wrestling with big ideas here, the soulfulness of food, the history of Spain, the disconnectedness and alienation of modern life, and the fundamental nature of narrative and its place in our lives. Complicating this is his attraction to the rustic Castilian lifestyle and a deep longing to find his own place in the world. Paterniti yearns for simple country comforts and rich narratives with amusing digressions. As he’s drawn deeper into Ambrosio’s world, he becomes less satisfied with parts of his own life. He doesn’t have what he sees in Ambrosio and the cheese. As he says in the book, “It may sound strange to call a cheese soulful, but that’s what this cheese seemed to be, just by sight.”

I don’t think it sounds strange that a cheese can be soulful; it sounds right on the money to me. Eating an artisanal cheese connects you to the flavors of its land and, because cheese-making is an ancient alchemy, it connects us as well to human history and all the emotions that fuel it.

For a book that is in many ways about food, Paterniti manages to brush off superstar chef Ferran Adrià with only a passing mention. Apparently Adrià ’s famous cheese foam did not impress. The foam is made by blending cheese with heavy cream until it forms a smooth liquid, then straining it into a whipper, and, assuming you didn’t already use up the nitrous oxide by filling balloons and doing “whips,” charging the mixture with the gas. What comes out looks a bit like Cheez Whiz, only lighter. And while it might be interesting, does the introduction of technology make the end product inherently better? To that Ambrosio would say, “I shit in the milk of God!” Which doesn’t make a whole lot of sense, but you can feel the emotion behind it.

Adrià ’s molecular gastronomy stands in opposition to Paterniti’s quest for authentic experience. For the author, food tells a story, and the introduction of technology only adds a layer of separation between the eater and the story of the food. Cheese is foamed, animals are parsed into rectangles and squares, fruits and vegetables become unrecognizable as “confetti” or reduced to gastriques. What is fancy, sometimes even delicious, is in essence processed food, and processed food is alienation: it disconnects us from the plant or animal, the farmer, the land, the sun and air, the specificity and history of time and place. Even if the science itself fascinates — with exotic ingredients like agar-agar, calcium lactate, soy lecithin, xanthan gum, and sodium alginate — the result can be sterile and soulless. At its worst, molecular gastronomy is a techno-nightmare, a pretentious and overwrought narrative about nothing but the technology itself.

Carry that a step further, as Paterniti does, and the technology we use to live our lives, the digital devices, the streaming wi-fi, the Pads and Pods and Fires and Glass that never leave our sides, are also keeping us from connecting to the world in an authentic way. Why ask your device what the weather is like if you can just walk outside? How can we connect to people if everything is spun through a digital filter? And what kind of stories are we telling each other if we’re alienated from the physical world? If I “like” your post, is that a story?

Another element runs through the book that I find as compelling as the story of the cheese or the author’s quest for genuineness, and that’s a meditation on the idea of storytelling itself. The culture of this part of rural Spain seems to require adults to spend their evenings sitting around a table drinking wine, eating chorizo, and spinning yarns in their “telling rooms.” Paterniti is a writer, a professional storyteller, and he naturally finds this lifestyle compelling and, ultimately, addictive. Even better, this way of telling stories informs the structure of the book — narratives digress through extensive footnotes that frequently lead to stories within stories, just as they do in the telling room. It’s an ingenious narrative conceit.

But my favorite part of this complex stew is Paterniti’s struggle to wrest the narrative from Ambrosio and his mythmaking and, as deadlines pass and book contracts are cancelled, to try to tell the story in a more professional way. And while Paterniti eventually uncovers conflicting versions of the story of the cheese and Ambrosio’s betrayal, this ambiguity doesn’t lessen the power of the narrative. It adds layers, as ambiguity almost always does. There is no right or wrong. We can choose whom to believe.

At some point the parallel narratives begin to merge as Paterniti struggles to integrate what he has grown to love about Ambrosio and the Castilian way of life with his own life and — forgive me if this sounds corny or overtly Jungian — to find himself.

As the English writer G.K. Chesterton once observed, “Poets have been mysteriously silent on the subject of cheese.” While Michael Paterniti might not be a poet, the garrulous Ambrosio has the soul of a poet trapped in a cheesemaker’s body, energized by Don Quixote’s adventurous spirit. That The Telling Room expertly brings Ambrosio to life and sweeps the reader (and the author) along on his picaresque tale of epic cheese-making is a singular accomplishment.

Like all good love stories there is an ultimate consummation between the author and the “pure and transcendent” cheese that has haunted him for 20 years. It reads like a delicate sex scene, and I don’t want to spoil the fun by revealing the more salacious details, but I was struck by Paterniti’s conclusion: “I’d like to pretend it tasted like love or history or God — if those things possess a real taste — that its molecules reshaped my own and created a flash of insight, but you know, it tasted like … really good cheese.”

Paterniti opens his narrative with this quote from Pascal: “Imagination magnifies small objects/With fantastic exaggeration/Until they fill our soul.” What’s important is that our souls are filled, and why shouldn’t it be by a really good cheese?

¤

Mark Haskell Smith’s fifth novel, Raw: A Love Story, will be published in December.

LARB Contributor

Mark Haskell Smith is the author of Heart of Dankness: Underground Botanists, Outlaw Farmers, and the Race for the Cannabis Cup, Baked, Raw: A Love Story, Blown, and other books. His latest is Rude Talk in Athens: Ancient Rivals, the Birth of Comedy, and a Writer’s Journey through Greece (Unnamed, 2021). He is an associate professor in the MFA program for Writing and Writing for the Performing Arts at the University of California Riverside, Palm Desert Graduate Center.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!