My Daughter Took the Bullet for Me: On Talent and Celebrity Dynasties

Ariella Garmaise considers Romy Mars’s viral TikTok through the lens of her mother and grandfather’s film “Life Without Zoë.”

By Ariella GarmaiseApril 17, 2023

“I’M GROUNDED because I tried to charter a helicopter from New York to Maryland on my dad’s credit card because I wanted to have dinner with my camp friend,” says Romy Mars, daughter of Sofia Coppola and Phoenix front man Thomas Mars, in a now-viral TikTok from March 22. Romy has since deleted the video—her parents banned her from public social-media accounts because, she explains, they don’t want her to receive backlash about being a “nepotism kid.” But the snippet was an intoxicating peek into the lives of the children of the rich and famous. Watching the 16-year-old, whose candor and preternatural charisma (as well as her breakneck speaking pace in the sped-up video) catapulted her to brief internet celebrity, I couldn’t help but recognize in her the same hammy, poor-little-rich-girl magnetism that courses through her mother’s body of work. More specifically: Romy seemed a near double of the titular lead in 1989’s short film Life Without Zoë.

Directed by Romy’s grandfather Francis Ford Coppola and co-written and costume-designed by a then-teenaged Sofia, Life Without Zoë follows the charmed life of an Eloise-inspired preteen who presides over Manhattan from her luxury hotel suite. “Once, I was in debt,” she sighs to Hector (Don Novello), her butler and guardian. “I was in debt so much that with all the deductions [my mom] took out of my allowance, I didn’t even have enough money to pay for taxis!”

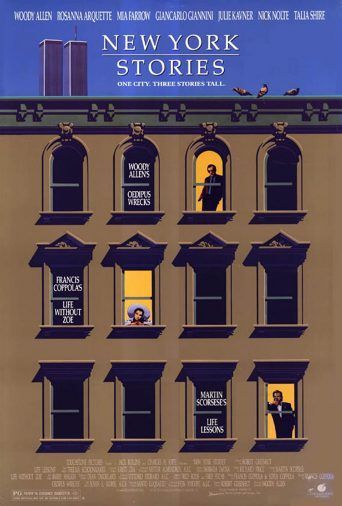

In the film, 12-year-old Zoë Montez (Heather McComb) reigns at the Sherry-Netherland hotel, where her parents have left her in the care of a kindly butler while they travel the world. Her father is a flutist so talented that, in Zoë’s words, women cannot help but “g[e]t themselves seduced” by his music. The frenetic plot, which loses coherence early into its brief 36-minute runtime, follows Zoë’s efforts to return a lost diamond earring to an Arabian princess before its absence spoils both the princess’s marriage and Zoë’s own parents’ reconciliation. Released as one of three shorts in the New York Stories anthology film, Life Without Zoë, which ends with the Montezes reunited and set to escort their daughter on a shopping trip to Paris, seems to have sprung from a preadolescent fever dream.

Programmed between shorts from Martin Scorsese and Woody Allen, Life Without Zoë is generally considered the weakest of the triptych. A New York Times review derided it as “remarkably giddy and slight” and having a “prevailing message [that] is more or less Marie Antoinette’s.” Sofia, of course, would respond to this criticism 17 years later with Marie Antoinette, and with films such as Lost in Translation (2003), Somewhere (2010), and The Bling Ring (2013), an oeuvre unified by its earnest explorations of girliness, privilege, and stuff. Life Without Zoë fulfills the secret childhood fantasy of having a director stumble upon your scribbles and send them straight to Hollywood, and it is precisely that remarkable giddiness that makes the film so delightful.

In Life Without Zoë, Sofia’s sensibility emerges nearly fully formed. That the rich, famous, and politically connected beget children who are also rich, famous, and politically connected is nothing groundbreaking, but we can only hope that they’re as honest about it as Sofia was at 16. Critics of nepotism in Hollywood will, rightfully, point out that Sofia’s trajectory has not been bent earthward by the financial strife or lack of opportunity that most filmmakers face (her debut short film starred Peter Bogdanovich). But whereas so many “nepo babies” neurotically conceal their wealth, qualifying their fortune or self-flagellating over their privilege, Life Without Zoë doesn’t pretend to be anything that it’s not. It’s impossible to imagine anyone but Sofia having written this movie, and it’s impossible to imagine her at this age writing anything else.

As outlets like The New York Times, Vulture, and The Guardian debate the role of nepotism babies like Sofia—and now Romy—Life Without Zoë is a reminder of the strangely endearing side of nepotism. Francis Ford Coppola’s project evokes envy not just for the money spent or connections leveraged to jumpstart Sofia’s career, but for the faith he has in his daughter. In Life Without Zoë, we see a father’s unwavering admiration for his child, and his willingness to do all in his power to see her artistic potential realized.

With the help of three-time Academy Award–winning cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, Francis actualizes his daughter’s vision absent any condescension—or, seemingly, script notes. In Francis’s view, the trappings of femininity (like the virgin daiquiris and copies of Vogue Paris that litter Zoë’s hotel room) are no less worthy of careful attention than the organized crime in The Godfather (1972) or the Vietnam War in Apocalypse Now (1979). From its title sequence, which employs a Curlz MT–esque font and refers to Francis and Sofia by first name only, Life Without Zoë relishes in the girlish. Zoë lives a 12-year-old’s dream: she writes middle school gossip columns with her cosmopolitan retinue, hails taxis when she misses the school bus, and paints portraits at her desk next to a bottle of Chanel No. 5 the size of her head. With Storaro’s careful lensing, a scene in which Zoë and her tween friends interview “one of the richest boys in the world” while twirling pastel parasols and batting paper fans captures the glamor and playfulness of a Renoir painting.

This adult treatment of the childish crystalizes in Zoë, who is both nine and 45 but never 12, a girl careening between naivete and savvy who needs her butler to pick out her clothes in the morning but warns her mother to ditch padded blazers because “a woman shouldn’t have bigger shoulders than a man.” Francis has no interest in diluting his daughter’s imagination—Zoë showers a panhandler with Hershey’s Kisses (“She’s why I love New York!” he responds), a foreshadowing of Kirsten Dunst’s “Let them eat cake” in Marie Antoinette.

Francis Coppola filmed Life Without Zoë at the nadir of his career. A decade removed from the Oscars and commercial success of films like The Godfather, Apocalypse Now, and The Conversation (1974), the 1980s proved to be a period of disrepute for the director. He lost all $26 million that he personally invested in 1982’s One from the Heart and began making a string of box office bombs to diminishing critical returns. In 1986, while working on a third installment of The Godfather and filming Gardens of Stone to recoup his squandered fortune, Francis’s 22-year-old son Gian-Carlo was killed in a boating accident. The director would spend the rest of his career trying to make sense of this loss. While promoting 2011’s Twixt, a film about an author grappling with writer’s block caused by guilt over his daughter’s death in a boating accident, Coppola fought back tears. “Every parent feels that they’re responsible for whatever might happen to their kid,” he told journalists. Zoë’s joyfulness and confidence in the world she’s already conquering emerges from this tragedy; it’s touching that Francis might try to preserve that bubble. New York Stories asked three directors what Manhattan means to them: Allen answered predictably with a domineering mother, Scorsese a lover, and Coppola his daughter.

Like The Godfather, Life Without Zoë is a family affair. Francis cast his sister, Talia Shire, as Zoë’s mother, and had his father, composer Carmine Coppola, cameo as a homeless flutist. According to Zoë’s narration, the baby music that her father played on his silver flute was the first sound she ever heard—art is also a family business, Francis seems to say. When Francis suggested his daughter for a role in The Godfather Part III, Paramount Pictures told him they would sooner pay the price for any Hollywood actress, even Madonna. Still, he insisted on Sofia, whose performance was almost universally panned. “The daughter took the bullet for Michael Corleone—my daughter took the bullet for me,” Francis would go on to say when faced with accusations of nepotism.

Maybe this incident explains Romy’s previous absence from TikTok. But talent, unfortunately, is not democratic. So, while there are surely scions that have no business on camera, when Romy struggles to differentiate between onion and garlic while cooking pasta alla vodka (she’s holding a shallot), she still hints at the same spark that has lit up so much of her family tree. Francis Ford Coppola’s filmography suggests that there are priorities even higher than art—the best part of being successful is probably helping your kids to do something even better.

¤

LARB Contributor

Ariella Garmaise is a Toronto-based assistant editor at The Walrus. Her writing and cultural criticism have been featured in Lit Hub, Catapult, The Walrus, and other outlets.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Going Klear: A Glass Onion Franchise in the Wild

J. D. Connor asks why Netflix spent $450 million to acquire the “Glass Onion” franchise.

It’s All Pastiche: On Todd Field’s “TÁR”

Paul Thompson reviews Todd Field’s “TÁR.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!