Art Young, the Legend, Revisited

Paul Buhle reviews "To Laugh That We May Not Weep: The Life and Art of Art Young."

By Paul BuhleSeptember 9, 2017

To Laugh That We May Not Weep by Art Young. Fantagraphics. 480 pages.

NEARLY 80 YEARS AGO, one of the sweetest books in the history of American radicalism appeared: Art Young: His Life and Times. A wonderful memoir in every sense, it encompassed and expressed the beloved socialist artist’s saga, from Midwestern small-town boy suspicious of radicals to the greatest of all radical cartoonists in the English language. He hated the spoils of capitalism and war with a ferocity scarcely to be equaled in art anywhere, Picasso or John Heartfield or Spain Rodriguez notwithstanding. But beneath Young’s rage, evident to any reader, could also be found a deep sense of sorrow at the outcome of civilization at large. A popular favorite, his drawing of a caged lion dreaming of free life in the jungle captures the aphorism of philosopher J. J. Rousseau, that “man is born free, but he is everywhere in chains.” Young would have added, indeed did add more than metaphorically in his many drawings over 50 years of work, that the rich and powerful did not seem to suffer so greatly, but nevertheless bore the scars of meretricious lives.

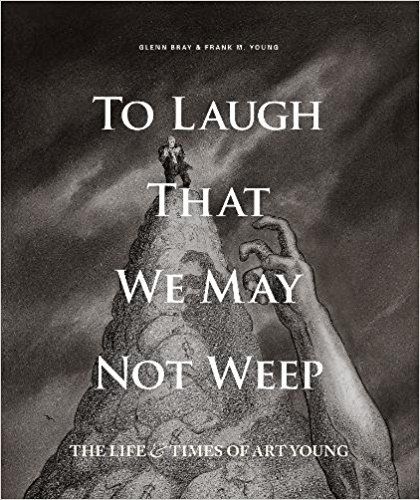

To Laugh That We May Not Weep, edited by Glenn Bray and Frank M. Young, is the successor volume to the memoir in many ways. Appearing long after Young himself has slipped down the memory hole of American popular cartoon art, this is a massive volume in every sense, with the format designed to highlight hundreds of forgotten or rarely seen drawings located by a heroically hardworking circle of book and printed art collectors. The book design, by Fantagraphics’s own Sean David Williams, is remarkable in its sheer luxury of space, the feel of the work highlighted, and the meticulous reproduction of varying paper and ink qualities in order to bring out every detail possible — down to Young’s own handwriting noting captions to be added. No books devoted to 20th-century artists, at least none reaching my desk, have been awarded more loving treatment, and it shows.

There remain, nevertheless, definite — one might say inevitable — problems of understanding and appreciating the richness before our eyes. Young’s work escapes easy categorization surprisingly often, and much of the “found art” in the volume is undated. The editors have responded in part by arranging the illustrations using nearly a dozen topical chapter categories (e.g., “Fantasy & Musings,” “Quotation Cartoons,” “On Religion”) rather than chronological ones — although some chapters, like the one dedicated to Young’s drawings for the Saturday Evening Post in the 1920s, encompass discrete phases. Young’s captions to his own work, periodically interspersed throughout the book, are wonderfully wry. The reader is left, at any rate, to enjoy a great deal of diverse Art Young work without the kind of systematic, detailed annotation that a smaller volume would have allowed. The 19th-century material is easily recognizable by style, the rest less so. But perhaps there is a value in the transhistorical Young, beyond such precise specifications.

Let us return to Young’s personal saga, explored in several essays beginning with Art Spiegelman’s. In Spiegelman’s phrase, “Young finds a way to hate the sin but not the sinner that arises from his deeply ingrained sense of humor, manifested in masterful exaggeration.” Here Spiegelman has captured the keystroke of the art itself, but artistic exaggeration was by no means Young’s only move. His crosshatching, shading, sense of perspective, and more look so easily accomplished that we forget that he took his craft as seriously as any master painter. By the time that he came to socialist convictions, at age 40, he was already an admired figure of graphic expression in the world of newspapers and magazines — at least by those who knew the fields and recognized his talent.

Young’s story begins with a childhood in little Monroe, Wisconsin, where his family moved a few years after his birth. The countryside was nearby (and still is). Here, in his childhood and later visits home, the past lingered or, perhaps, hung heavy. The mostly local population, although loyally Republican, did not, as he later wrote, concern itself much with politics. Young’s father, a fairly prosperous grocer, allowed the boy time and opportunity to become an observer of the locals’ collective personality, which led to a wonderfully humorous series drawn in the 1930s. Who had a new barn (or even buggy), where the honeymooners visited, and what relatives they saw along the way — these were among Monroe’s most discussed topics, even as the national economy went up and down, and vast protest movements appeared and disappeared. In this environment, human interest early on caught Young’s artistic eye.

Young wanted to be an artist at least from the moment that he discovered a Doré volume in the local library. By age 15, when the Chicago papers had just begun publishing pen drawings, he got a few items published and began to be viewed by locals as hugely promising. Thomas Nast’s famed contemporary drawings of Boss Tweed understandably won Young’s attention. He got a drawing of his own published in Judge, a comic weekly, gathered up his best work, and headed for Chicago.

Picking up little fees for drawings, Young got into the Chicago Daily News — where he covered the anarchist trials, sometimes showing a little sympathy for the defendants, but mainly his own ignorance — then the Tribune. Then he went to New York, where at the Art Students League he studied the works of the great satirists intensely. He received an offer from a popular writer to travel to France and illustrate essays for another of Chicago’s papers, the Inter Ocean, which featured an elaborate pictorial weekly edition. He planned to study for a year in Paris. Instead, he became seriously ill and recovered slowly, at first in Paris and then back in Monroe. In a way, even these events were fortuitous. Young and his friends created a little Vaudeville-type show with Young doing fast crayon drawings, accompanied by music — sometimes by a chorus of young women! He had become an entertainer.

Recovered and already a veteran of sorts, Young covered the World’s Columbian Exposition, which put Chicago itself on the world’s stage. Addressing the scandal-ridden creation of the Exposition, he might have moved along in a political vein. But his drawing developed in a way that no self-conscious radical or even political-minded illustrator would predict. Following his own instincts, he marveled at the rubes in the White City seeming to enjoy themselves while being fooled in one way or another. Diverse examples of human foolishness abound in these drawings, which are especially abundant in the pomp of the wealthy. (In a drawing reproduced here, Young contrasts women’s fashionable open-toed shoes to the “airy” care-worn shoes of the poor: a cryptic political note.) Meanwhile, drawing for himself as much as for the press, Young began his lifelong practice of putting into artistic form the obstacles that hindered any aspiring young person, including himself, from attaining some distant goal. Lack of opportunity, blind egotism, alcohol, and assorted other stumbling blocks made the promised land of achievement seem further and further away.

Young experienced no such failures in the short run. As Rebecca Zurier has described the big city world of the 1910s in her marvelous volume, Metropolitan Lives, the newspapers struck gold with drawings of everyday life, affording a cadre of mostly young artists the opportunity to make a decent living. The American flâneur was born, along with the sophisticated tastes that would make both the Armory Show and Ashcan realism possible. Meanwhile, Young married, took newspaper jobs as far from New York as Denver, freelanced with considerable success, and moved to Bethel, Connecticut, where he spent most of the rest of his life. Still a Republican of the progressive sort, he was drawn, at a distance, to the great idealist governor of his native state, Robert M. La Follette. He headed back to Wisconsin for the electoral campaign of “Fighting Bob.” He then returned to New York, where he drifted out of marriage and into socialism.

Now his drawings for Life (the light-hearted, pre–Henry Luce publication) tended toward the downright radical, mixed with comical memories of the old hometown and its inhabitants, among other subjects. The Socialist Party press was flourishing by this time, and he was eager to make up for lost time politically. Still, he remained a few years away from his apex.

This would be his work for The Masses magazine, founded in 1911 to support the cooperative movement but refounded, the following year, as a heavily illustrated, avant-garde magazine. Marc Moorash, an archivist and book dealer personally intent upon reopening the Bethel gallery of Young’s creation, supplies a fine mini-essay on Young and The Masses. In it he highlights some of Young’s most magnificent political art, most especially but by no means only on the themes of war and class exploitation. Reeking of Greenwich Village temperament, Ashcan art offered up slum life seen without condescension, but with a touch of humor and wonder. The Ashcan school would be rejected by the European avant-gardist abstractionists of the Armory Show. Yet it remained the most forceful American innovation at home.

The Masses, meanwhile, was a magazine of a sort previously unknown on either side of the Atlantic. Young had been hired full time before the changeover, but another native Midwesterner, younger yet close to Young’s temperament, now entered as full-time employee: Floyd Dell. Dell was fresh from Chicago, where he had edited a weekly literary supplement. Still under 30, raised near Davenport, Iowa, he had the sort of sprightly mentality, optimism, and sense of humor perfect for Young. With the arrival of the brilliant young journalist-agitator Max Eastman and the creation of a board that included major artists John Sloan and Maurice Becker, The Masses made history.

There was nevertheless something anomalous about Young’s presence at the magazine. His work had an old-fashioned look in a publication that radiated a youthful ambience. He was unlikely to enter the social world of free love in Greenwich Village, and it is hard to believe that he would have had the stamina for the social life around the magazine. Rather, he seems to have worked in Bethel and taken the train in for editorial meetings and social events. He was already the notable old-timer, admired by all, but somehow distant.

Young himself described his situation, in words quoted in To Laugh, as “having a free hand on The Masses to attack the capitalist system and its beneficiaries.” This made him feel akin to “a crusader […] set forth to rescue the Holy Land from the infidels.” This phrase is worth mulling over, because Young actually sought to save civilization’s accomplishments from those capitalist-minded creatures he thought would surely destroy it. His art from this era, especially vivid in To Laugh, speaks for itself, depicting a time of intense class struggle, an imperial invasion of Mexico, and impending repression as something far worse approached.

Woodrow Wilson’s administration put The Masses on trial for sedition in 1918, guaranteeing the destruction of the magazine — the administration’s aim — without, however, successfully sending any artist to jail. That Young produced so much humorous work about the trial shows his strength of character, or perhaps just his commitment to his art. Nearly 50, in a movement of young people, he portrayed himself as plump and mild, a nebbish among Bolsheviks. Meanwhile, his commercial outlets dried up. He drew for The Masses’s successor radical magazine, The Liberator, as much as he could allow himself at the low pay on offer. Good Morning (1918–’23), his very own comic publication, brilliantly designed, with staggeringly beautiful drawings, could only be a financial failure. Beloved of the bohemians, he was no businessman. And besides, the left was largely in hiding. Eugene V. Debs, the socialists’ 1920 candidate for president, campaigned from a prison cell or two. Yet Young remained a much-desired artist in numerous circles, especially in New York, and found enough commercial work to stay afloat.

So little is said of Young’s private life in these pages that we might wonder if he had any. He married a hometown girl, they bore two children, and after several attempts at domestic life, he gave up, his wife moving to California with the kids. Young continued to support the family, he and his wife never divorced, and, after his death, his widow seems to have moved to Bethel. Did a clever, modest fellow, almost cute in his pudginess and sometimes with plenty of money, attract girlfriends? We see unnamed women in photographs of his later years, and wonder. Perhaps intense work, good food, and drink filled his life to the brim.

Young certainly had his arty side. Justin Green, one of the strangest and most influential underground comic artists, was selected by the editors to introduce Art’s little book of trees viewed as displaying philosophical truths or human characteristics. This series, writes Green with only slightly exaggerated phrases, is “as close to immortality as popular art can achieve,” sans the “gravitas and pretension of fine art.” Now, in a planet facing extinction, the trees have grander meaning, a kind of botanical greatness.

Young returned, during this later period, to his favorite themes, most especially the continuous reinterpretation of Dante’s Inferno. The impact of Doré’s version upon the young lad prompted him to make his own, first in 1892, then in 1901, and finally in 1932, when he produced the definitive Art Young’s Inferno. By the time this final version was published, Young had done many drawings of hell, his special hell, for popular magazines that included the Saturday Evening Post. These are painful, socially critical, and above all hilarious — much of the humor about living in New York or any modern metropolis — while still being deeply humanistic. By the time of his final adaptation of Dante, Art himself was the traveler, undisguised.

Within a decade or two, before his work slowed down to almost nothing, in 1940, he had passed through other cycles of art and politics, including his own literary versions of artistic history. Thomas Rowlandson (1938), a 54-page extended pamphlet in a trade book series on historic popular artists, is perfectly charming in its own right, with crisp prose. So were half a dozen earlier little picture books excerpted in To Laugh. In all, the book’s bibliography lists almost two dozen pamphlets or booklets that were essentially illustrations of others’ writings.

After the suppression of The Masses and The Liberator, Young did occasional work for the New Masses, now more closely connected with the Communist Party than its predecessor. When he died in 1945, it was the New Masses that devoted a special tribute issue to him (whose cover To Laugh reproduces). It seems likely that he appreciated the best qualities of the Popular Front, with its abundance of artistic talent united against the threat of fascism.

Young had never been one for romanticizing Bolshevism, and he never seems to have reconciled himself entirely to FDR or the New Deal, which he suspected of saving capitalism (charge true) and blazing a path toward war (also true). He even ran for Congress on the Socialist Party ticket in 1934, shortly before the party took a nosedive. He could have predicted political failure for himself as a candidate, and probably did. He certainly saw fascism in all its horrors, but the socialist alternatives seemed to disappear around him. Besides, his health was waning and his interest in his little museum of his own work in Bethel had grown apace. Perhaps he mainly liked to meet and greet friends old and new.

By the time Art Young died, he had perhaps in some ways outlived his artistic time. The newer leftish art, from 1930s WPA murals to 1940s war posters, seems to have passed him by. Or had it? His own illustrator’s era, set in place before the photograph’s domination of newspaper and magazine pages, lay generations in the past. But the political cartoon is forever. If today we find in the best examples of this art a fine touch, a satire of class society, an underlying sadness at where all our so-called progress has got us (as well as the flora and fauna of the planet), we see Art Young again and again. The brilliance and humane qualities of his work are as real in these pages as they ever were. Reader, dig in.

¤

LARB Contributor

Paul Buhle co-edited the outsize oral history tome Tender Comrades, with Patrick McGilligan, en route to several other volumes on the Blacklistees with co-author Dave Wagner, including A Very Dangerous Citizen, the biography of Abraham Lincoln Polonsky. He is the author or editor of 35 volumes including histories of radicalism in the United States and the Caribbean, studies of popular culture, and a series of nonfiction comic art volumes. He is the authorized biographer of C. L. R. James.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Graphic Spinoza

An excerpt from "Heretics! The Wondrous (and Dangerous) Beginnings of Modern Philosophy."

Hollywood! With the Reddish Tinge: Clancy Sigal’s 1950s

Anything could happen in Clancy Sigal’s 1950s.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!