Are The Fools in Town Still On Our Side?: A Ross Thomas Retrospective

Why has Ross Thomas fallen out of favor?

By Woody HautAugust 2, 2013

IT'S NOT UNCOMMON these days to stumble across some critic extolling the merits of the latest hotshot crime writer. When it comes to crime fiction, flavors-of-the-month are a dime a dozen, and self-parody is an occupational hazard. At the same time, there are a number of excellent noirists who have either been forgotten or, for one reason or another, remain unrecognized or underappreciated. Amongst these one would have to add the name of Ross Thomas, surely one of the best crime writers of the last 40 years. Having written some 25 books, including his incomparable Chinaman’s Chance (1978) and five under his well-chosen nom-de-plume Oliver Bleeck, Thomas, even at his worst, is no less compelling than the great Elmore Leonard — though perhaps not so self-conscious or style-obsessed.

At some point during the 1990s, not long before his death, Thomas seemed to fall out of favor. It’s hard to understand why; his books always sold reasonably well. Moreover, he had been a favorite of such diverse readers as John D. MacDonald, Eric Ambler, Lawrence Block, Donald E. Westlake, and President Bill Clinton, as well as that renowned cultural critic Lynne Cheney. Even Stephen King, having stated that Thomas was “the Jane Austen of the political espionage story,” compared him to Don DeLillo.

¤

Born in Oklahoma in 1926, Thomas’s writing cut across social and political classes. He wrote with equal ease about those at the top or at the bottom of society’s ladder. So class-ridden are some of Thomas’s characters that they appear to have leapt from the pages of a British spy novel into the rarefied atmosphere of suburban small-town America. As wealthy editor Nancy deChant Orumber says to tough-guy Mike Padillo in Thomas’s The Backup Men (1971):

You look as though you may have acquired a few of the social graces along the way. There’s character in your face. Some would call it dissipation, but I choose to call it character. You may pour the wine.

Others — like political fixer Indigo Boone, who in The Porkchoppers (1972), has graduated from a small-time real estate investor to a Chicago political fixer responsible for swinging the 1960 election in JFK’s favor — are self-made, raised in the midst of the American nightmare and schooled in cheap bars and shady deals.

An old-school liberal with a provocative CV, Thomas was well-qualified to write about political intrigue and the trickle-down theory of crime: the notion that corruption starts at the top of our culture and floats downwards, moving, as one particular Thomasite put it, from the suites to the streets.

Stylistically free and easy, Thomas swung more in the direction of well-structured and humorous plots on the one hand, and eccentric and unpredictable characters on the other, regardless of whether they held down jobs as diplomats, spies, politicians, activists, lobbyists, cops, or con artists. Not only did Thomas cover a wide range of criminal types, he loved to punctuate his work with references to political finagling, trade union machinations, and the effect of various social movements. He once said, “I weave historical facts and observation […] What is eavesdropping to others is research to the novelist.” Ross Thomas was no idiot. And maybe that too counted against him.

So readable is Thomas that you’d think he’d spent a lifetime honing his literary chops. But like Raymond Chandler, Thomas began writing at a relatively late age. In fact, The Cold War Swap, which won an Edgar for Best First Novel in 1967, was written when Thomas was over 40 years old and in between jobs, having never previously thought about writing fiction. He gave himself six weeks to churn out a book. After finishing it, he sent out the manuscript, and within two weeks it was accepted for publication. Given its plot, revolving around scientists trapped behind the Iron Curtain, The Cold War Swap holds up quite well. This is largely due to the book’s setting in Bonn, where Thomas had been working as a diplomatic correspondent for the Armed Forces Network. The experience informed his storytelling: as far as Thomas was concerned, spying was just one more pathetic folly, as comic as it was dangerous.

¤

Anyone who reads Thomas with any attention might soon wonder if he was in fact a spy. His biographical details give plenty of room for speculation After serving as a US infantryman in the Philippines during the Second World War, Thomas finished his studies at the University of Oklahoma, then became a public relations operative first for the National Farmers Union and later for VISTA — the latter culminating in his only nonfiction book, Warriors for the Poor: The Story of VISTA, Volunteeers In Service to America. He then worked as the representative of Patrick Dolan Associates in Nigeria, where he became the campaign organizer for tribal chief Obafemi Awolowo in his efforts to become that country’s first postcolonial prime minister. He would later use Nigeria as a setting for his novel The Seersucker Whipshaw.

After Nigeria, Thomas was employed as a political consultant in Washington, followed by a stint as a diplomatic correspondent in Bonn. He also put in time as a reporter in Louisiana, as well as in Washington DC, and as chief strategist for two trade union presidents seeking reelection. In 1956, he handled two campaigns simultaneously, one for a Republican nominated for the Senate and the other for a Democrat running for governor of Colorado. The Republican lost, but the Democrat won. He is also reputed to have worked for Senator and future presidential hopeful George McGovern. Eventually, the union presidents would be turfed out of office, while the Nigerian prime minister lost his next election and was duly thrown in jail. As for McGovern, he, of course, became President Nixon’s target in the Watergate burglary. A spook by any other name could not have positioned himself any better.

Thomas, tongue firmly in cheek, would only admit to being a “former civil servant,” which, in itself, can mean anything. He clearly had no problem inserting his job-related knowledge into his fiction. When that knowledge needed to be supplemented, he was always willing to put in the necessary research — yet another skill picked up in his “civil service” days — if only to add that extra bit of verisimilitude. This was definitely the case in his 1970 novel The Fools in Town Are on Our Side. The title, which comes from Huckleberry Finn — “Hain’t we got all the fools in town on our side? And ain’t that a big enough majority in any town?” — says it all. Of course, it might also have referred to his own experience, particularly when it came to his political work. The Fools in Town Are on Our Side introduces another one of Thomas’s protagonists: Lucifer Dye, a former espionage operative. Unemployed, Dye forms an alliance with an ex–call girl in the fictional Gulf Coast city of Swankton. One of the most unforgettable images in the book occurs near the beginning, in which a four-year-old Lucifer Dye clings to the severed hand of his dead father during the Battle of Shanghai in 1937. A small but important recollection, it was written only after Thomas had consulted numerous accounts of the battle.

Less about war than small-town corruption, The Fools in Town Are on Our Side contains another unforgettable character, the kind that Thomas excels at, in this case the tough and aptly-named ex-police chief Homer Necessary, a man with one brown eye and one blue eye, “neither of them contain[ing] any more warmth than you would find in a slaughterhouse freezer.” But even though Homer is thoroughly corrupt, when it comes to personal matters he is completely trustworthy. It's a contradiction that crops up time and time again in Thomas’s work, where everyone is fallible and moves between extremes, their situations mirroring Thomas’s ambivalence regarding the Cold War and the way it was so easily able to corrode the culture.

Cultural corrosion plays prominently in Thomas’s work, perhaps no more so than in Chinaman’s Chance — in my opinion, Thomas’s best novel. Its complicated plot, filled with morally ambiguous characters, involves a female singing group at the center of a corrupt Los Angeles seaside community on the verge of being turned into a small-scale Las Vegas. Chinaman’s Chance also introduces two of Thomas’s most notorious protagonists: pretender to the Chinese throne Artie Wu, and fellow adventurer Quincy Durant (who also features in Thomas’s 1987 Out on the Rim and in his penultimate novel, Voodoo, Ltd., published in 1992).

¤

While Chinaman’s Chance is agruably his best work, Thomas wrote several others over the course of his career, many of which take place in a small corrupt town. Briarpatch is one of the strongest of these. It takes place in Texas or Oklahoma, though one is never quite sure. Wherever it is, it’s hot:

The redheaded homicide detective stepped through the door at 7:30 A.M. and out into the August heat that already had reached 88 degrees. By noon the temperature would hit 100, and by two or three o'clock it would be hovering around 105. Frayed nerves would then start to snap and produce a marked increase in the detective's business. Breadknife weather, the detective thought. Breadknives in the afternoon.

The heat permeates the novel, slowing down its inhabitants, but not the plot. Situated in the center of this unnamed town is a giant clock to which the narrator constantly refers, recording the time and pacing the novel. With five grand in the bank, and a used Volkswagen, Ben Dill finds himself in Washington, DC, unemployed, trying to figure out what to do with his life. He returns home to investigate the car-bombing murder of his sister. It’s another one of Thomas’s corrupt town novels, not all that far removed from the work of Sinclair Lewis or Robert Penn Warren, populated with the kind of greedy, petit bourgeois merchants one finds in Dodsworth and Babbitt. Awarded an Edgar in 1985, Briarpatch contains Thomas’s typical mix of characters: a hero only slightly less tarnished and tainted by corruption than the villain, who, par for the course, turns out to be vulnerable, deadly, slightly ludicrous, and all too human.

Another of his corrupt town novels, The Fourth Durango (1989), sounds like it might be set in Mexico or Colorado, but instead, it takes place in a small town in California that functions as a hideout for businessmen, scamsters, and predators attempting to avoid their designated hit men. Picture a slightly less frenetic and surreal version of Jim Thompson’s kingdom of El Rey in The Getaway, and you get the idea. With inhabitants paying large sums of money to keep their would-be killers at bay — the money goes to paying for public services hit by free market cuts — a former state Supreme Court chief justice arrives in town, followed by his son-in-law, who becomes an emissary to the beautiful and streetwise mayor. A phony priest follows the former chief justice and his son, leaving behind a trail of corpses.

A year after this small masterpiece, Thomas’s Twilight at Mac’s Place appeared. This one concerns the memoirs of a recently deceased spy that contain some Cold War secrets certain people don’t want in the public domain. When the son of the spy is offered 100 grand for the rights to the memoirs, he becomes suspicious and seeks out the help of Thomas’s old protagonists McCorkle and Padillo, who by now have seen fit to invest in a bar that bears the book’s title. Small-time entrepreneurism seems to appeal to Thomas’s protagonists, though they are all too easily lured back into the world of spooks and scams.

¤

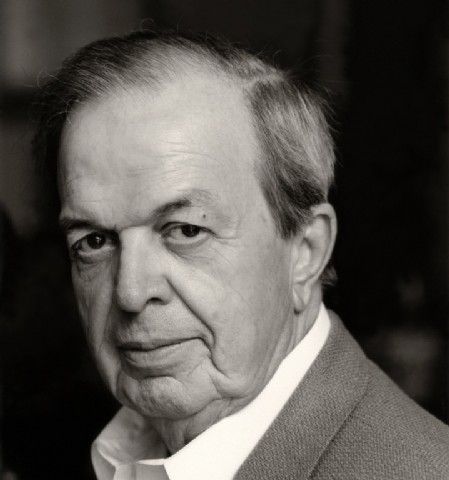

Unfortunately, no one seems to have had the nerve to ask Thomas about the murkier side of his past. He was never someone to whom you could easily address such questions. Though by all accounts he was polite and generous, with a dry sense of humor, there was a diffidence about him more reminiscent of a habitué of a London gentlemen’s club, or refugee from an E.M. Forster novel, than a writer of tough-guy novels. With pale skin, piercing eyes, and in later years, thinning hair, Thomas spoke with an Oklahoma accent. So much did he avoid the limelight that at the annual Bouchercon, he would spend most of the conference playing poker with fellow renegades. Then it was back to his writing desk in Malibu, where he and his wife, Rosalie, lived for most of their 25 years together, having met in Washington where Rosalie worked as a librarian at the Library of Congress, and Ross did his research.

Thomas’s comedies of manners exist in a world that was post-Chandler but pre-Ellroy. After all, he had lived through McCarthyism, the California real estate boom, the New Frontier, the Great Society, the rise of the middle class, inflation, recession, stagflation, consumerism, Watergate, Reaganomics, and decades of American greed and foreign intervention. Though his books are political, Thomas was smart enough to cloak their politics in an off-beat, even surreal humor, the lightness of which sets them apart from John Le Carré’s somber tales of agents wrestling with their demons, crippled by the pointlessness of their activities. For Thomas’s characters, and probably for the author, the Cold War, whatever its effect on the culture, constituted merely a series of obstacles to overcome.

As for Chandler, Thomas credits him with helping to save his life. According to Thomas, a little over an hour after landing on an island in the Philippines in 1945, his first scout handed him a copy of Farewell, My Lovely. He was 18 and surprised to find the book was set on the mean streets of Los Angeles. The scout was later killed, and Thomas lost the book on the beach. Taking over his job, Thomas spent the next 100 days or so wondering who Velma was. “I decided,” he said in an article he wrote for The Washington Post in 1984, “I needed to be Philip Marlowe safely back in Los Angeles in that palmy year of 1940 — in a time that would never change. It was a harmless enough notion that probably kept me sane.”

Regardless of how unsung he might be, Thomas had his share of admirers, if not in the US, then at least in France. The late great polar writer Jean-Patrick Manchette fell under his spell. Meeting at a writer’s conference during the last decade of Thomas’s life, he and Manchette quickly became friends. As well as extolling his work in various periodicals, Manchette translated Thomas’s novels into French. Moreover, his reading of Thomas contributed to his decision to abandon crime fiction in favor of a type of espionage novel, perhaps not as humorous as Thomas’s but even more political, exemplified by Manchette’s unfinished and posthumously published La Princesse du sang.

Not surprisingly, Thomas also had his share of admirers in the world of cinema. Film-wise, he is still best known for co-writing Wim Wenders’s 1982 film, Hammett. In putting together what would become a well-intentioned failure, Wenders went through some 30 screenplays before he settled on Thomas’s and Dennis O’Flaherty’s. Through no fault of their own, and despite a workmanlike script, the film contains none of the narrative drive and only a fraction of the energy of Joe Gores’s revisionist novel on which the movie is based. Yet the film contains a number of memorable moments, and remains one of the few films to tackle the subject of writing on any level other than the most mundane. Thomas would also be given a small role in Hammett, playing a corrupt local politician. A decade later, he was credited with writing Damian Harris’s Bad Company, starring Ellen Barkin and Lawrence Fishburn. Again, not exactly Citizen Kane, but an interesting effort, particularly when it came to Thomas’s labyrinthine script. And six years before Hammett, there was St. Ives, starring Charles Bronson and Jacqueline Bissett, adapted from a story by Thomas’s alter ego Oliver Bleeck. But for the most part, Thomas’s heroes are too duplicitous, and his narratives too ironical and convoluted, for most directors to easily adapt for the screen.

In 1993, Thomas lost his manuscripts, his books, including various foreign translations of his novels, as well as his typewriter — he hated computers — in a Malibu fire. Undaunted, he and Rosalie moved to Point Dume, where despite their loss, life continued as usual. For Thomas, that meant returning to his daily writing routine. It was a persistence that marked all his work — “I rewrite virtually everything […] even notes to the guy who delivers the bottled water” — and extended to his never-give-up fictional creations. When he wasn’t writing, Thomas liked to go to the cinema. He once said that one of the benefits of being a writer was that he could go to the movies in the afternoon.

Two years after the fire, and a few months after finishing his novel Ah, Treachery!, Ross Thomas died of lung cancer at the age of 69. Of course, within a couple years, most of his work would be out of print, and remain so for the better part of a decade. Fortunately, St. Martin’s would eventually reprint many of his works, each accompanied by introductions from the likes of Donald E. Westlake, T. Jefferson Parker, Robert B. Parker, Sara Paretsky, and Lawrence Block. I’m still waiting, however, for a full-fledged Ross Thomas revival. It’s nothing less than he deserves.

When asked what it was like being married to a writer, Thomas’s wife Rosalie replied, “Very quiet.” Asked if her husband was ever a spy, she simply smiled and said, “Not that he ever told me.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Raised in Pasadena, but now living in London, Woody Haut is the author of Pulp Culture: Hardboiled Fiction and the Cold War; Neon Noir: Contemporary American Crime Fiction; Heartbreak and Vine: The Fate of Hardboiled Writers in Hollywood; and of the novels Cry For a Nickel, Die For a Dime and Days of Smoke.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!