Anne of the Armistice: Girls’ Book Heroines Confront the Great War

Looking back at YA novels of the home front on the centennial of the World War I Armistice.

By Perri KlassDecember 1, 2018

RILLA OF INGLESIDE (1921), the last of Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables novels by internal chronology, contains the following sentence on its opening page:

There was a big, black headline on the front page of the Enterprise, stating that some Archduke Ferdinand or other had been assassinated at a place bearing the weird name of Sarajevo, but Susan tarried not over uninteresting, immaterial stuff like that; she was in quest of something really vital.

The year, obviously, is 1914, and the world is about to change. Anne herself has long since grown from child to adolescent (in Anne of Green Gables and Anne of Avonlea [1909]), taught school and gone to college (in Anne of the Island [1915] and Anne of Windy Poplars [1936]), married her childhood sweetheart (in Anne’s House of Dreams [1917]), and raised a large family (in Anne of Ingleside [1939] and Rainbow Valley [1919]). The Rilla of the title is her youngest child, but — significantly for a Canadian mother in 1914 — Anne also has three sons, the oldest just 21. And while we may remember orphan Anne and school-girl Anne and romantic Anne, the series actually culminates with a novel about that faraway cataclysmic war and the way it transforms the lives of the families on Prince Edward Island, tracing an arc from the Sarajevo assassination to the Armistice that ended the conflict, 100 years ago this November.

Anne Shirley, that red-haired orphan, came to Green Gables in the 1870s. She was 11 years old, plucked from an orphanage by people she had never met who were willing to take in a child to help with the work. Anne arrived by horse and buggy, of course. She was met at the station by Matthew Cuthbert, a shy and lonely fellow who lived with his sister, Marilla, at Green Gables farm. It’s a very 19th-century story. Yet, as Anne grows up amid the idyllic natural beauties of Prince Edward Island, she is moving, with the world around her, toward a very specific date with history — a crash encounter with the modern world at its most cruel and terrible. If you were 11 in the early 1870s, then you would be pushing 50 in 1914, with children old enough to fight in a war whose global reach encompasses your tiny island.

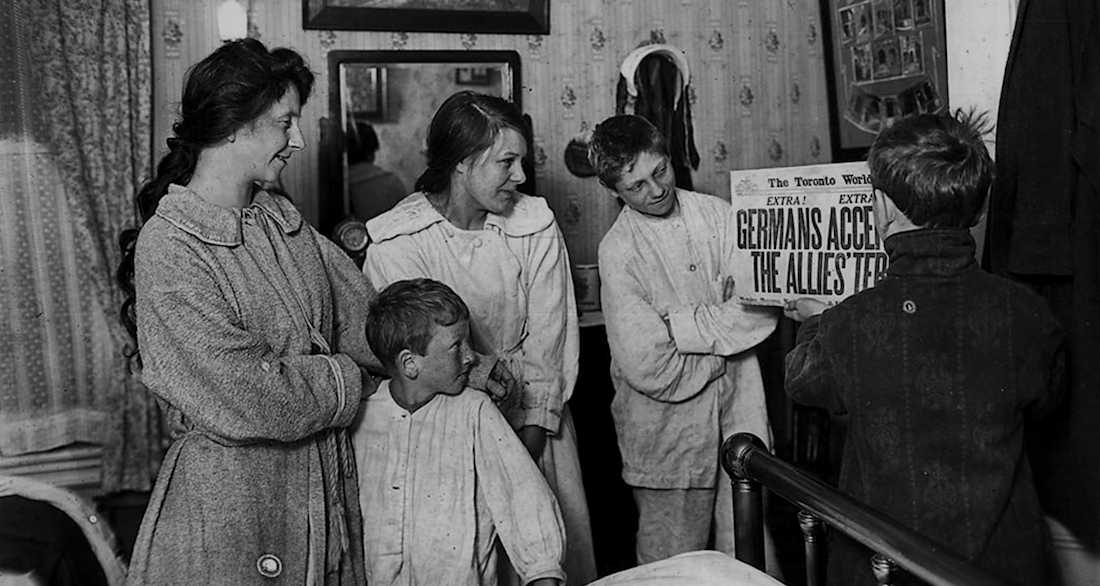

Rilla of Ingleside is in fact a rather extraordinary war novel — or, rather, home front novel, apparently the only Canadian novel of World War I written by a woman who lived through those times. When Great Britain enters the war, Anne’s oldest son, Jem, is among the first to volunteer, because, he says, “we’ll all have to turn in and help […] [W]e couldn’t let the ‘old grey mother of the northern sea’ fight it out alone, could we?” Over the course of the story, all three of Anne’s sons leave to fight in distant battles, which their family back home follow with passionate interest. You can track the whole trajectory of World War I in Rilla of Ingleside, as the folks on Prince Edward Island nervously wait for the newspapers, the casualty lists, the phone calls and telegrams, as they train themselves to pronounce foreign place names, from Przemysl to Passchendaele, and people their conversations with such international celebrities as Kitchener and Hindenburg and the Kaiser. Rilla, Anne’s youngest daughter, is, at the beginning of the book, a somewhat heedless 16-year-old girl with no ambition other than to look pretty, yet soon she is organizing the Junior Red Cross, getting up a concert to help the starving Belgians, masterminding a war wedding for a frightened friend who wants to marry her soldier boy before he departs, and taking in a war baby whose mother died in childbirth while the father was at the front.

Though her stories have been periodically updated, Nancy Drew doesn’t age. When I read the books, she drove a “roadster” that matched her blue eyes, which in later editions became a convertible, then a hybrid. Despite these fashion changes, however, Nancy herself is immune to personal chronology and to history. But children crave coming-of-age series, in which the main character matures and the tenor of the narrative keeps pace — think, most recently, Harry Potter. As five-year-old Betsy Ray, in Maud Hart Lovelace’s Betsy-Tacy books, grows up to be a high school girl in turn-of-the-century Minnesota, the storytelling grows along with her, and the simple sentences and child-centered plots of the early books — Betsy-Tacy (1940) and Betsy-Tacy and Tib (1941) — turn into what we would now call young adult novels about, well, young adults. And unlike Harry Potter and his sorcerous friends, Betsy and Tacy and Tib grow up in the world we know, where the late 19th century turns inexorably into the early 20th, and the delights of modernity — the telephone, the telegraph, the horseless carriage, the gramophone — also herald the approach of zeppelins, air raids, machine guns, and poison gas.

Betsy finishes high school, starts college at the University of Minnesota, but doesn’t thrive there, and so, since she wants to be a writer, her parents send her abroad, alone, in Betsy and the Great World (1952) — which is set, like Rilla of Ingleside, in 1914. Betsy crosses the Atlantic, lives in student lodgings in Munich, then in a pensione in Venice. She studies German grammar and romances a handsome young Italian, while still yearning, always, for her high school sweetheart, Joe Willard. There are intimations of German militarism — the mustachioed, uniformed officers in her Munich rooming house swagger around as if they own the place — but mostly Betsy loves all things Teutonic. There is no suggestion in the book that the continent is on the verge of cataclysm — until Betsy finds herself in a bohemian boarding house in London, in the early summer, as Europe prepares to go to war. She and her friends wait up late to hear the British declaration of war on the radio, then stand at the window singing “Rule, Britannia.” And then she heads for home and Joe.

Betsy’s Wedding (1955), the last in the series, is another World War I home front novel. Betsy and Joe get married and settle in Minneapolis, where Joe goes to work for a publicity office that is raising money for the Belgians. The war comes in and out of the story — Betsy dances to “Tipperary,” and she recalls the British soldiers she watched march off to war in London, as well as the friends she made in Munich. Tib, whose family is German-American, is fiercely anti-Kaiser. But mostly, Betsy’s Wedding is true to its title: it’s a girl-grows-up story about love and marriage — until the end, when the United States enters the war and Joe joins up. So a novel about newly married life, about the ups and downs of learning to cook and keep house, becomes a novel about following the Great War from afar, watching it come so close that it results in rationing (“meatless and wheatless” days) and begins to claim the local young men. The novel ends with Tib marrying her own soldier, with sabers crossed above their heads in an army toast and a sword to cut the cake, before the men go off to fight.

These are war novels told from the viewpoints of young women — Rilla is 15 at the beginning of the war and Betsy is 22. The girls are fairly traditional in their behavior, though of course World War I ushered in changing roles for women and was fought amid a roiling controversy over women’s suffrage in both England and the United States. Rilla and Betsy do not expect the war: it comes suddenly and horrifyingly into their relatively untroubled girls’-book worlds of parties and dances and dresses, flirtations and family and friends. The two heroines are not exactly children, but they are fairly fresh from their childhoods — which means, of course, that they are close in age to the young men who go off to fight and die. Maybe that’s one reason these novels retain their poignancy — the girls who worry about their brothers and sweethearts remind us of how wars interrupt romances, interrupt educations, interrupt lives. They remind us that wars are fought by people very close to childhood.

The “All-of-a-Kind Family” novels of Sydney Taylor are set in a very different corner of the turn-of-the-century New World. These five books follow a set of orthodox Jewish sisters — five in all, dressed identically as children, hence the series title. In the third book, All-of-a-Kind Family Uptown (1958), the girls have made a triumphant move to the Bronx, leaving behind the Lower East Side, and the oldest daughter, Ella, has grown up enough to have a boyfriend, Jules. When war breaks out in Europe, Jules enlists — not, like Montgomery’s Jem, to help the mother country, but because of his Jewish identity. As he tells Ella: “You know tyrants have always tried to destroy us. In exactly the same way Germany is now trying to destroy little Belgium. Tyrants must be stopped — the sooner the better.” When Jules returns on leave, he brings along a non-Jewish comrade, Bill, for Ella’s Irish girlfriend, Grace, and the novel tracks the happy double date — and then the later anguish when Bill goes missing in battle, presumed dead. In New York City, as in Minneapolis, the war means meatless days and heatless nights: “People were urged to do without sugar, meat, fat, flour, so that these might be shipped to the soldiers and to our starving allies.”

Unlike Betsy’s Wedding, which ends with the war still raging (it is widely believed that Lovelace planned at least one more volume, in which Betsy would have a daughter of her own, but she never wrote it), All-of-a-Kind Family Uptown continues through the November 1918 Armistice and beyond. The book ends with a parade through the Victory Arch at Madison Square Park, a grand structure erected for the occasion by Mayor John F. Hylan, and with Papa’s pronouncement: “We have managed to live through all this terrible time, and now the world is at peace.”

Sydney Taylor published this book in 1958, so she knew, of course, that the world would not stay at peace, and that German militarism had not been stopped. Similarly, Betsy’s Wedding appeared in 1955, so Lovelace knew that the Great War had not in fact ended all wars. Montgomery, on the other hand, released Rilla of Ingleside in 1921, in the shadow of the recent Armistice, and it is particularly poignant to read about the joy and relief her characters feel when peace returns, and their naïve belief that it will last. When word comes that “Germany and Austria are suing for peace,” Rilla, now so much more mature after the long years of war, cries out: “I have walked the floor for hours in despair and anxiety in these past four years. Now let me walk in joy. It was worth living long dreary years for this minute, and it would be worth living them again just to look back to it.”

Rilla of Ingleside, for all its melodrama and stilted patriotic rhetoric, can still dependably make a reader cry. I tear up when Susan, Anne’s faithful housekeeper, runs the Canadian flag up the flagpole: “She was one of the women — courageous, unquailing, patient, heroic — who had made victory possible. In her, they all saluted the symbol for which their dearest had fought.” Montgomery ends her home front story on a note of faith and optimism. As Rilla writes in her diary: “We’re in a new world,” Jem says. […] [“]The old world is destroyed and we must build up the new one. […] I’ve seen enough of war to realize that we’ve got to make a world where wars can’t happen.”

When I reread Rilla today, I no longer identify with the adolescent protagonist but instead with the mother who watches her sons go off, one after another, to fight in the trenches. Montgomery’s schoolgirl heroine had passed into matrimony, motherhood, and middle age, and so the book centers on Rilla, a perfect girls’ book heroine, surpassingly interested in dress, headstrong and high-spirited, prone to adventures and flirtations, with growing up to do and lessons to learn. Although Anne is a relatively minor character in the novel — the wise mother, emerging every now and then from the wings to offer some sage advice or sensible comfort — she’s still a presence. And of course, if you grew up reading the Anne books, she’s an old friend.

Anne of Ingleside — which is set a little earlier, when Rilla and her siblings are still children — ends with Anne, the happy matron, going from room to room to check on her sleeping children. Looking in on her son Walter, she notices that the window bars cast the shadow of a cross on his wall. “In long after years Anne was to remember that and wonder if it were an omen of Courcelette […] of a cross-marked grave ‘somewhere in France.’” Walter, the poet, is initially tortured by the knowledge that he is too afraid to enlist. He stays in college, where people begin to snub him — or worse — because he is not in khaki. And then the Germans sink the Lusitania, and he is outraged enough to overcome his fear and join up. On the European battlefield, he writes a poem, “a short, poignant little thing. In a month it had carried Walter’s name to every corner of the globe. […] A Canadian lad in the Flanders trenches had written the one great poem of the war.” Montgomery surely had in mind the poem “In Flanders Fields,” which was written by a Canadian surgeon at a battlefield hospital near Ypres.

Walter doesn’t make it home — as you will have no doubt guessed from the omens and cross-marked graves. And Rilla of Ingleside does an extraordinary job of conveying the anguish and worry of having sons far away in the trenches, fighting endless bloody battles to take and retake small pieces of ground, while at home you have to go on living and working and, all the time, tracking the faraway battles, waiting for the casualty lists, asking again and again, as Rilla writes in her diary, “Over there in France tonight — does the line hold?”

Series books set in the real world must take into account the actual turns of history. The horseless carriage replaces the horse and buggy. New dances become popular. The world goes to war. And finally, a hundred years ago this November, the war comes to an end and the soldiers left alive can come home to their waiting families. “Did I ever say November was an ugly month?” Rilla asks when the Armistice comes.

Why it’s the most beautiful month in the whole year. Listen to the bells ringing. […] They’re ringing for peace — and new happiness — and all the dear, sweet, sane, homey things that we can have again now […] Soon we’ll sober down — and “keep faith” — and begin to build up our new world. But just for today let’s be mad and glad.

At this centennial moment, as we rethink and reinterpret the enduring legacy of World War I, it’s interesting to reread these narratives of children growing up into their historical destinies. They do not know they are a war generation, but they are carried forward by time, which moves as inexorably as any book series.

¤

LARB Contributor

Perri Klass is professor of journalism and pediatrics at New York University. She is the national medical director of Reach Out and Read, a program that works through pediatric primary care to promote parents reading with children. Her most recent books are Treatment Kind and Fair: Letters to a Young Doctor (2007) and the novel The Mercy Rule (2008). Her short stories have recently appeared in Glimmer Train, Agni Review, and New England Review, and she writes the weekly column “The Checkup” for The New York Times.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Pedagogic, Not Didactic: Michael Cart on Young Adult Fiction

On the growing sophistication of YA fiction and its audience.

It’s Okay That Anne Shirley Never Became a Writer

Anya Jaremko-Greenwold on L. M. Montgomery’s “Anne of Green Gables.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!