An Intimate Utopia: On Nabaneeta Dev Sen’s “Acrobat”

Shruti Swamy reviews “Acrobat,” a volume of Nabaneeta Dev Sen’s poetry translated by her daughter Nandana Dev Sen.

By Shruti SwamyOctober 22, 2021

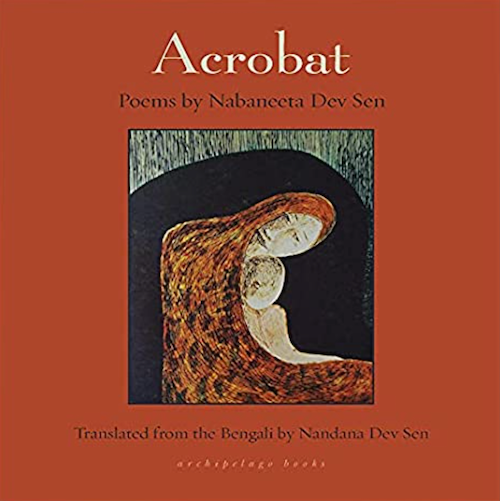

Acrobat by Nabaneeta Dev Sen. Archipelago. 120 pages.

FOR A WHILE, I could not put my finger on the quality that so moved me in the language of Acrobat, an anthology of Nabaneeta Dev Sen’s poetry translated by her daughter Nandana Dev Sen. The poet’s voice comes through clearly even in translation — it speaks to the reader as it would a friend, very honestly, at times playfully, and never anxiously — in words that feel plainspoken but not austere. This voice describes the poet’s life: of motherhood, loss, and frequently, the mercurial work of making poems. It also speaks, sometimes elliptically, about topics that lend themselves to abstraction, like the nature of time, or life. Nandana’s excellent translations privilege the musicality and rhythm of the language, retaining, in some cases, the internal rhymes. Most of the poems are quite brief: dense jewels surrounded by white space. As I describe them, I find myself reaching again and again for words like clarity, honesty, brilliance. But I think the word I am really searching for is freedom.

“Do you break your home just for poetry / Time and again?” the speaker asks herself in “Broken Home.” Dev Sen herself divorced her husband in an era when divorce was nearly taboo, and for a time, she banished herself from poetry. Yet, in a poem like “Broken Home,” there is no self-castigation, no shame. The poet’s pleasure in the “glow” and “dazzle” of language is too evident, too seductive, to read these lines as containing regret. The question is posed in the present tense, as though poetry — a wild, upheaving force — will continue to compel the poet to answer this question. One gets the sense that the poet’s persistent reply is a joyful “yes.”

Or take the sly poem “Be Quiet,” in which the speaker entreats her “noisy heart” to “hush.” These requests immediately call to mind the many ways women have been asked to silence themselves, until we see the cause of her request: the fear that the commotion will wake “heaven, earth and hell.”

Stop, stop this rush in my veins —

If I let my blood gush like the rains,

It will flush away the whole universe.

Far from being weak, the speaker possesses a tremendous, even overwhelming strength, which she celebrates even as she tries to negate it, or at least, chastise it. Who else has the power to “flush away the whole universe,” but a god?

The theme of godliness continues in the speaker’s meditations upon motherhood. “Twice now, pretending to be a goddess / I’ve created humans out of my desire,” she writes in “Puppet.” The singular authorship of the child, “I” instead of “we,” calls to mind Parvati’s creation of Ganesha, who she made from dust, out of desire for companionship while Shiva was away. The speaker relinquishes her power in the next line: “the fake goddess act ends. / After that, you revert to being a woman,” where much is out of her control. But she cannot let go of the idea of divinity altogether. As she looks into the mirror she wonders if “[s]omewhere it lies hidden, the secret divine will” or if it was just a “momentary spark.” The radiant, transcendent experience of making life has expanded the speaker’s idea of her own capabilities — she is even a little disturbed by her power. There is awe at the mystery that moved through her to create her two children, an awe that echoes her reverence for the act of writing: a similar sense of wild creation.

Yet, there is room for vulnerability here. “Did I ask for too much then?” the poet wonders in “Too Much.” Very reasonably, all she wanted was “two eyes, nothing more.”

No dawn, no dusk, no long night —

not food, nor clothes, nor shelter

Neither remembrance nor reflection,

But a moment’s attention, to be erased

in the next moment — that’s all.

Still, did I ask for too much?

This poem could be read as an admonishment to an indifferent lover, who, far from providing the speaker with food or shelter or spending with her a long night, will not give her even a moment’s attention. But, whose eyes is she asking for: a lover’s or her own? For isn’t this the plea of a writer, who needs her two eyes and her attention to see into the heart of the moment? Read this way, the vulnerability in “Too Much” is the shadow of the joyous defiance of “Broken Home,” the repetition of the question in the first and last lines voices the doubt that the other poem rejects — a question that holds a note of plaintive loss. Still, alongside that doubt is the absolute clarity of desire, ambitious desire. Whether or not the poet has asked for too much — she still wants it. So here, even at her most hurt, the poet remains blazingly honest: giving voice to her desire, with doubt, but without apology.

Nearly all the poems in Acrobat, which span the arc of Nabaneeta’s long career, were translated into English from Bangla by her daughter Nandana Dev Sen (a small number were composed in English, and a few of the poems written in Bangla translated by the author herself). The difference between the poems written in English and the Bangla poems are palpable, if hard to articulate — I found a greater sense of intimacy in the Bangla poems, a beautiful plainness, and sweetness. Writing in Bangla was a political choice for Nabaneeta, according to the comprehensive and often moving introduction by Nandana. A polyglot, Nabaneeta was a noted scholar of Indian literature, translator, editor, and a champion of works written in Indian regional languages. The choice of English would have afforded her much: both greater audience reach and the freedom of relative anonymity, freedom from the mores and conventions of her time and culture. She was aware of these affordances, as her own words (quoted by Nandana in the excellent and often moving introduction) attest: “In English I could express my anger, my thirst, far more openly and powerfully, irrespective of a reader’s sentiment, because I was addressing a faceless reading public.” I understand this. Before my grandmother died, we had a long, intensely intimate conversation, in English — my only language, and her third. Speaking aloud in English, a language wholly outside her mother tongue, my grandmother spoke with a sense of privacy that allowed her to voice things I suspected she had never before said, even to herself.

It is remarkable that Dev Sen might have forgone a similar sense of privacy, instead creating for herself, in her mother tongue, and in her native culture, a utopia with her words, where anything can be felt and said, without fear, without shame. This is a world populated mostly, but not entirely, by women — girls, children, friends, to whom a few poems are addressed, and the many iterations of the speaker herself: women to whom she could say anything. That these poems are translated by her daughter, to whom one of the poems is also addressed, only heightens this feeling. Words like “fearless” or “shameless” still admit the existence of the things they negate. These poems are messages from a world where those words and their opposites are meaningless. A free world.

¤

LARB Contributor

Shruti Swamy is the author of the story collection A House Is a Body, and the novel, The Archer, both from Algonquin Books. The winner of two O. Henry Awards, her work has appeared in The Paris Review, McSweeney’s, and elsewhere. She is a Kundiman Fiction Fellow, and lives in San Francisco.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Learning Bengali and Comparing Notes with Jhumpa Lahiri’s “In Other Words”

Anandi Mishra overcomes the obstacles of language in “Learning Bengali.”

The Hazards of Immersive Journalism: A Conversation with Sonia Faleiro

An acclaimed Indian author of narrative nonfiction discusses the challenges and ethics of her craft.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!