An Amazon of the Avant-Garde: On Lynn Garafola’s “La Nijinska: Choreographer of the Modern”

A well-researched biography of a neglected major choreographer of avant-garde dance.

By Harlow RobinsonMarch 24, 2022

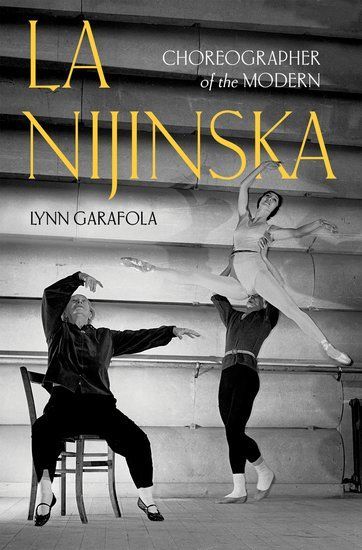

La Nijinska: Choreographer of the Modern by Lynn Garafola. Oxford University Press. 688 pages.

BY THE TIME Bronislava Nijinska visited Los Angeles for the first time in 1934, at the age of 43, she had survived several bloody revolutions; divorced one husband and married another; given birth to two children; witnessed the descent into madness of her much more celebrated dancer brother, Vaslav Nijinsky; traveled the globe as a freelance choreographer from her hometown of St. Petersburg to Kyiv and Paris and Buenos Aires; and established herself as what dance historian Lynn Garafola describes, in her voluminous, meticulously documented, and welcome biography, as an “Amazon of the Avant-Garde.” Whew! Just to read about Nijinska’s endlessly creative and frequently impoverished vagabond existence is exhausting. Imagine what it must have been like to live it.

Nijinska came to Hollywood at the invitation of renowned Austrian stage and film director Max Reinhardt. He was co-directing (with William Dieterle, recently arrived from Germany) the 1935 version of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream for Warner Brothers and hired her to choreograph a few ballet sequences. The polyglot production exhibited the sophisticated working atmosphere in the film business at the time. Besides Reinhardt (who spoke almost no English), Dieterle (who translated for him), and the Russian-speaking Nijinska, the distinguished crew included composer Erich Wolfgang Korngold, freshly arrived from a brilliant career in Austria, and Polish set designer Anton Grot.

Nijinska had already been working for a decade with dancers who spoke a variety of languages and “had mastered the art of speaking with her body rather than words.” As was always her custom, even into old age, Nijinska demonstrated the steps to the dancers (including very small children) herself, often gesturing with the cigarette-holder that was her nearly constant companion. One observer described her as “spritely, agile and eager.” A Midsummer Night’s Dream gave Nijinska’s career a “tremendous boost,” and her lucrative Hollywood salary enabled her to pay off the crushing debts she had accumulated while trying to run ballet troupes in Paris and supporting a family and assorted spongers.

Like many other Russian creative artists — Igor Stravinsky, Vernon Duke, Sergei Rachmaninoff — Nijinska (born in Minsk in 1891 to Russian-speaking Polish parents) would eventually find permanent artistic and personal refuge in Los Angeles. She spent the years of World War II here, opening her own Hollywood Ballet School and performing at the Hollywood Bowl. “I can’t explain how good and beautiful it is here,” she wrote to a friend in 1940. “I am being offered a job, also in a school, in New York, but neither Ira [her daughter] nor Nik [her devoted second husband, Nicholas Singaevsky] want to even hear about leaving California.” After the war, she maintained a residence in Los Angeles but traveled frequently to New York, Europe, and Buenos Aires for engagements as a choreographer. Finally, in 1954, she and her husband bought a small house in Pacific Palisades, with a view of Potrero Canyon Park to the south and the Pacific to the west. This was the only home Nijinska ever had, and they lived in this peaceful spot until her death on February 21, 1972.

But as was the case throughout her life, even in her adopted home of Los Angeles, Nijinska never received the sort of respect or attention her long and groundbreaking career deserved. The Los Angeles Times ran an unsigned death notice full of factual errors and even got her daughter’s name wrong. As a “woman choreographer” working in a dance world controlled and dominated by males, Nijinska was often dismissed as “difficult,” “dictatorial,” even “ugly” (an adjective used to demean strong females in any profession). She suffered the fate of so many accomplished women in the arts, overlooked and minimized because of her gender. Her frequent critic, the acerbic British dance critic Arnold Haskell, called her “the only ugly dancer to find fame.”

It didn’t help, of course, that she bore the extra burden of living in the long shadow cast by her older brother Vaslav Nijinsky, considered by many to be the greatest male dancer who ever lived and revered as a god by balletomanes. As a choreographer, she refused to make compromises or ingratiate herself with famous figures, such as impresario Serge Diaghilev, creator of the Ballets Russes, or George Balanchine, co-founder of New York City Ballet. Nijinska, Garafola writes, “didn’t go in for parties with fancy people or bother with fashion,” and was bad at “theatrical politics.” In her tireless search for a synthesis of classicism and modernism, she “upset ballet’s conventions of heteronormativity” and threatened many in the dance establishment with her “female masculinity” and celebration of androgyny. “[F]or me ballet is a religion — and I am a fanatic!” Nijinska once confessed to her friend George Skibine.

But the tragedy of her nomadic life was that she never stayed (or was allowed to stay) in one place or with one company long enough to form a permanent tie or a strong base of operations. Consequently, her major contribution to the creation of a new kind of abstract modernist ballet — constructed around the credo that “movement is the principal element in dance” — has remained undervalued and under-researched. Sexism also helps to explain why her works “dropped from sight and memory” in postwar New York and London, as Garafola argues in her preface: “Nijinska’s career shows that women are certainly capable of being first-rate choreographers, but also reveals the barriers that have held them back.”

Nijinska could not have hoped for a more sympathetic and conscientious biographer than Garafola. An emeritus professor of dance at Barnard College and the author of the definitive study of Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes and other works of ballet and dance history, she has been writing and teaching and thinking about the development of the Russian classical style and its offshoots for many years now. A longtime close observer of the ballet world in New York and elsewhere, she understands the physical, educational, visual, dramatic, political, interpersonal, and financial aspects of the dance industry from the inside out. She can dissect and describe all the steps in how a choreographer builds a piece and how it looks on stage. Her analyses of Nijinska’s works, including her masterpieces Les Noces (1923, set to the music of Stravinsky) and Les Biches (1924, set to the music of Francis Poulenc), are detailed and insightful. She includes in an appendix an invaluable list of works that Nijinska choreographed for a remarkable array of companies on several continents. Garafola has consulted a mountain of sources, including Nijinska’s memoirs and personal papers, some having only recently become available, which helps to explain why this is the first biography of such a major figure in the history of 20th-century dance.

Like so many biographers who have worked on a subject for a long period of time, Garafola at times becomes too enamored of her research at the expense of narrative. Her frequent and lengthy citations of reviews by many different critics become tedious and could have been summarized or abbreviated. The writing is always clear but occasionally dry. Events come and go and go and come and all too soon, in what can feel like a chronicle rather than a biography. I wanted to feel more of the emotional drama and pain of Nijinska’s courageous life and its incredible challenges: her father’s abrupt departure at age seven; a fraught relationship with a brilliant but mentally unstable brother to whom she was always compared; her unrequited passion for the operatic bass Feodor Chaliapin; an early troubled marriage and motherhood; the struggle to survive and create in revolutionary Petrograd, Moscow, and Kyiv; the death of her son Léo in a car accident; and the devastating impact of the condescension and envy she encountered in the gossipy, hothouse atmosphere of the Ballets Russes, where she was shrewdly and often cruelly manipulated by her second “bad father,” Serge Diaghilev.

Trained at the Imperial Ballet School in St. Petersburg like her brother, Nijinska was plucked from the corps de ballet at the prestigious Mariinsky Theatre by Diaghilev, who included her in the first seasons of his Ballets Russes in Paris from 1909 to 1911. She wanted not only to dance but to choreograph, so she returned to St. Petersburg in spring 1914, just before World War I and the Bolshevik Revolution would transform the world in which she had been living. Eventually she gravitated to Kyiv, where she and her family (now including two young children) lived until 1921 amid “desperate shortages of food, firewood, and water” and frightening political violence. Even so, she managed to create a vibrant School and Theater of Movement, and came to know other members of the thriving Soviet avant-garde, including artist and stage designer Alexandra Exter. Around her gathered a community of women who adored and sustained her creativity. The years she spent in Kyiv (with a 10-month interlude working in Moscow) were crucial in her development as a choreographer and thinker, pushing her toward a utopian and futurist view of what dance could be.

Finally, the worsening political and living situation forced her to make the difficult decision to leave her beloved school behind. In April 1921, with previously independent Ukraine about to become a republic of the new Soviet state, Nijinska undertook a perilous escape with her mother and children by bribing the border guards and wading across the Bug River to Poland. The next period of her life was spent mainly in Paris, with frequent forays to London and other European capitals, and then an extended sojourn in Buenos Aires, where at the Teatro Colón she created “a modern, professional ballet ensemble unrivaled until the 1940s anywhere in the Americas.” Her creative base remained the Ballets Russes through the 1920s, but the imperious Diaghilev repeatedly shoved her aside in favor of male dancers and choreographers like Serge Lifar, Léonide Massine, and George Balanchine.

The high point of her collaboration with Diaghilev was Les Noces, to which Garafola devotes an entire chapter. Both Stravinsky’s score, which framed Russian folk rituals of marriage in a startling, highly dissonant, and insistent modernist language, and Nijinska’s abstract and “anti-librettist” choreography attracted enormous attention from le tout Paris. Composer/critic Paul Dukas wrote that Les Noces (in which the women still dance mainly on point in classical style) “shatters all laws, defeats all classifications, and stands wholly and deliberately apart from all […] known ballets.”

Nijinska inspired fanatical loyalty in dancers, some of whom followed her wherever she went. A frustrating 15-month collaboration with a troupe created by the wealthy dancer and impresario Ida Rubinstein mainly to showcase her own meager talent produced an erotic spectacle based on Ravel’s Bolero, with the angular and striking Rubinstein in the lead, surrounded by a crowd of increasingly lustful men “wild with desire.” After Diaghilev’s death in 1929, Nijinska (the “prodigal daughter of the Diaghilev family”) became an itinerant choreographer, shuttling frantically between Paris, Vienna, London, Buenos Aires, New York, and Los Angeles, often on the edge of penury. Her adoring and very helpful husband Singaevsky was always at her side, even following her around with an ashtray. In 1932, she managed to put together her own company in Paris, Les Ballets Russes de Bronislava Nijinska, and persuaded her idol Feodor Chaliapin to participate, but she was unable to sustain the enterprise financially or creatively. With its demise, her “visionary, intensely personal work” began to decline, although she continued to create new dances until 1960, at the age of 69.

During her final decades in Los Angeles, Nijinska put much of her titanic energy into teaching. Among the students who danced for her at the Hollywood Bowl were such future stars as Cyd Charisse, who called “Madame Nijinska” a “great teacher,” and Maria Tallchief (later a prima ballerina at New York City Ballet and Balanchine’s wife). From 1947 to 1950, she worked for the Grand Ballet de Monte Carlo, run by the Marquis de Cuevas, who took the company on an extensive tour of South America, but their collaboration ended in a bitter dispute over the cumbersome and old-fashioned costumes the Marquis wanted for a new production of Sleeping Beauty.

Nijinska never stopped working. In the 1960s, she supervised acclaimed stagings of Les Noces, Les Biches, and other ballets for the Royal Ballet at Covent Garden, the Ballet Center of Buffalo, and Jacob’s Pillow. Too often minimized as “Nijinsky’s sister,” she never did manage, however, to finish her planned book on her celebrated brother, who had died in London in 1950 after spending most of his life in asylums, afflicted with debilitating mental illness. She blamed his ambitious and self-centered wife Romola for causing much of his psychological distress, and for pushing her aside. Nijinska did not even see Vaslav for the last 12 years of his life.

So, what was Nijinska’s legacy? Unlike George Balanchine, she never created a company that would outlive her. And choreographers, unlike composers, writers, or artists, do not leave behind scores or books or paintings that we can touch or see. Their ephemeral work can only be recreated by dancers and lasts only so long as it is on stage. Thankfully dances can be preserved on film for future generations, and some of Nijinska’s work has now been recreated and preserved in that medium. She also proved that a woman could be a successful and important choreographer, and provided a model for others, including her contemporary Martha Graham, Agnes de Mille (who found it difficult to acknowledge that she could be influenced by anyone), Twyla Tharp, and others. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, she “trained, groomed and inspired” hundreds of dancers, both female and male, who became stars in many major ballet companies around the world.

Owing to her gender and her personality, Nijinska developed outside the mainstream of the major ballet companies of the 20th century. “Artistically, she was alone, stubbornly so,” Garafola concludes. But she developed a new abstract and modernist approach to classical ballet, “offering a highly original approach to ballet aesthetics, composition, and technique.” Nijinska would certainly be pleased with this rich and compassionate account of her life and work, which restores her to her rightful place as one of the most adventurous, gifted, and intrepid pioneers in modern dance history, an “Amazon of the Avant-Garde.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Harlow Robinson is professor emeritus of history at Northeastern University, author of Lewis Milestone: Life and Films (2019), Sergei Prokofiev: A Biography (1987), and Russians in Hollywood, Hollywood’s Russians (2007), and editor/translator of Selected Letters of Sergei Prokofiev (1998). His essays and reviews have appeared in The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, The Boston Globe, The Christian Science Monitor, and other publications. In 2010, he was named an Academy Film Scholar by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Ballet in the City: Jewish Contributions to the Performing Arts in 1930s Shanghai

How European Jewish refugees brought ballet to China.

The Cold War Industry: On Louis Menand’s “The Free World” and Anne Searcy’s “Ballet in the Cold War”

Harlow Robinson weighs “The Free World” by Louis Menand against “Ballet in the Cold War” by Anne Searcy.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!