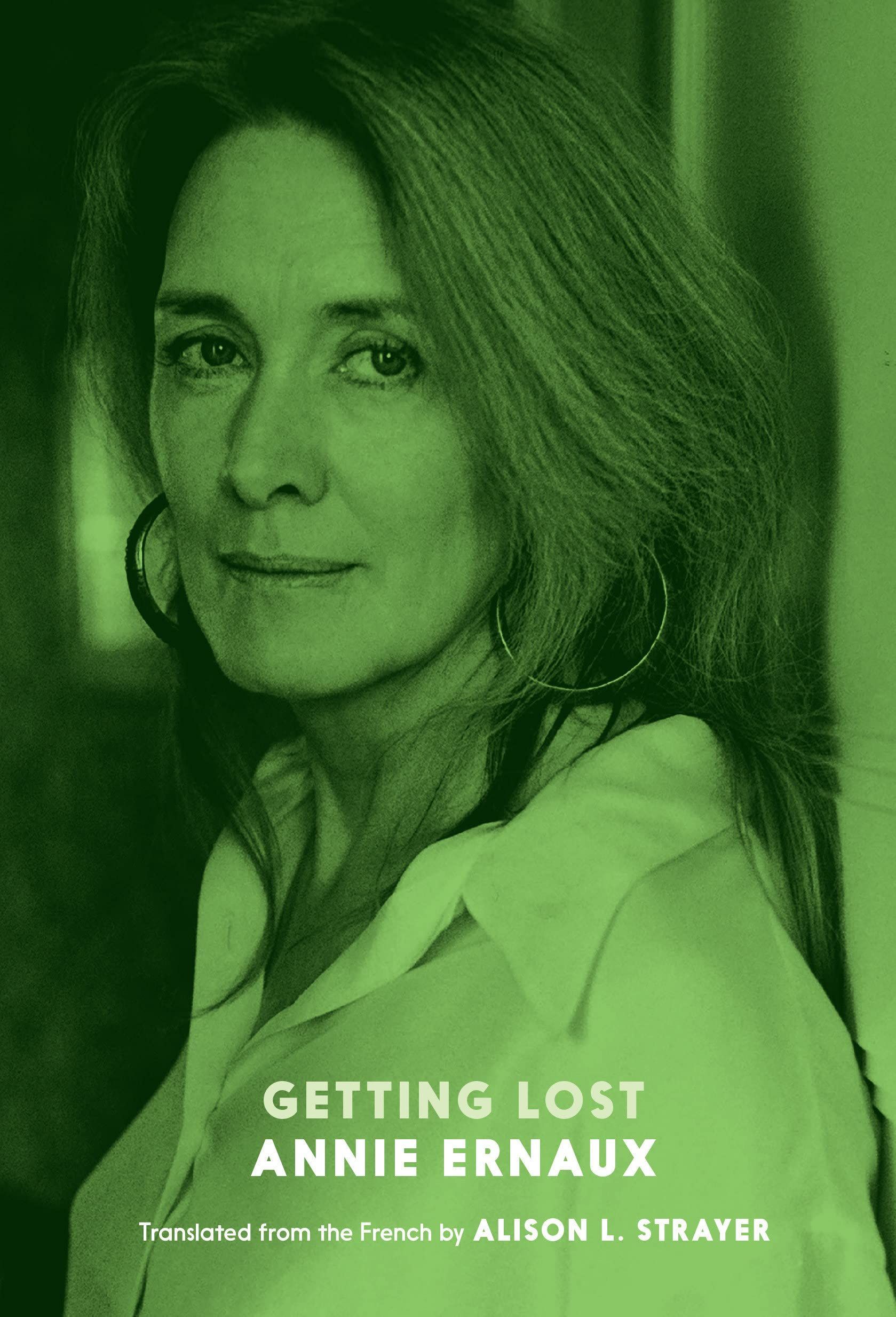

All That Really Happens Happens to Me: On Annie Ernaux’s “Getting Lost”

Kaya Genç surveys the work of Annie Ernaux via her memoir “Getting Lost,” translated by Alison L. Strayer.

By Kaya GençOctober 10, 2022

Getting Lost by Annie Ernaux. Seven Stories Press. 240 pages.

HOW TO DESCRIBE Annie Ernaux, the 2022 Nobel literature laureate? Novelist, diarist, feminist. Excruciating canvasser of a life riddled with shame. Master of autofiction, minus the laziness that infects certain practitioners of that overhyped genre. Nothing is superfluous in her writing; everything feels essential. A Calvinist, if not in religious conviction, then in literary style. Despite the diaristic shape of her books, a constant finder of le mot juste. Ernaux’s two dozen books, more than half of which have been rendered into English, all feel pruned to perfection.

Getting Lost, originally published in 2001 and now translated by Alison L. Strayer, comprises Ernaux’s diary entries from September 27, 1988, to April 9, 1990, a seismic era that saw the Berlin Wall fall and the Soviet Union start to crumble. Chronicling an affair with “S,” a married Soviet attaché based in Paris, it tells a tale told before in more exacting prose in Simple Passion (1991), a slimmer volume. Both books depict the same man, yet Ernaux’s penetrating gaze in Getting Lost excavates something crucial in her passion’s source — a fascination with Soviet culture. Today, as Vladimir Putin exhibits Russian militarism’s appalling face, this Russophilia makes poignant if troubling reading. Secretive, aggressive, and macho, Soviet culture attracts and appalls Ernaux in equal measure. At the same time, watching a skilled writer who was for years overlooked by the French literary establishment salvage an affair shrouded in such secrecy is to witness a literary feat.

Reading Ernaux’s books in succession is a demanding yet rewarding experience. Like Matryoshka dolls, her slim volumes resemble the shape of the ones written before them. They’re variations, each dealing with a specific subject, unearthing aspects of the author’s past. Ernaux devoted volumes to her mother’s dementia, her own painful abortion, and her aloof lovers. Pieces of her life’s puzzle are scattered in numerous tales; one must read them all to view the whole picture. One of her earliest books, A Frozen Woman (1981), offers striking tableaux of women from her childhood who refused to spend their time silently creating beauty and order, with “loud voices, untidy bodies that were too fat or too flat.” At the age of 10, Ernaux was fascinated by those women who refused to be submissive. Towering over them was her disadvantaged mother. She wanted a daughter “who won’t go toil in the factories as her mama did, who’ll be able to say shit to anyone and live a free life” — a task, some readers will attest, in which she succeeded.

At college, Ernaux feared these were her last free years. She began posing the big questions — “what do you do with your life?” among others — that have guided her life and her writing. She longed for the big city, to wander along “anonymous streets lined with tall old houses.” Meanwhile, she worked on a thesis on surrealism. But then she got married. In doing so, she would, she feared, “permanently lose my solitude.” She repressed those feelings, ashamed of her cowardice. Yet losing her solitude was, of course, precisely what happened. At the end of A Frozen Woman, Ernaux pushes a stroller, feeling “[j]ust on the verge, just.”

A Man’s Place, published two years later in 1983, paints a portrait of her father on a tinier canvas: “In his dark blue suit, which hung loosely around his body, he looked like a bird lying on its back.” Ernaux, resurrected after separating from her husband, receives her qualifications as a teacher. Delving into her mourning, she starts a novel in which her father is the main character, but “[h]alfway through the book I began to experience feelings of disgust.” A novel, she decides, was out of the question. “If I wish to tell the story of a life governed by necessity, I have no right to adopt an artistic approach, or attempt to produce something ‘moving’ or ‘gripping.’” What to do then? Her solution was to “collate my father’s words, tastes and mannerisms, as well as the main events of his life […] all the external evidence of his existence,” and portray him in the manner of a sociological study. “No lyrical reminiscences, no triumphant displays of irony. This neutral way of writing comes to me naturally. It was the same style I used when I wrote home telling my parents the latest news.” (Twenty-five years later, the technique has proved influential on a number of French authors, including Édouard Louis and Emmanuel Carrère.)

It took Ernaux eight months to wrap up her father’s memoirs; four years later, in 1987, she came up with another family monograph on her mother’s death from dementia. A Woman’s Story begins in a flat tone reminiscent of Albert Camus’s L’Étranger: “My mother died on Monday 7 April in the old people’s home attached to the hospital at Pontoise, where I had installed her two years previously.” Her consideration of death devastates because it’s told in this flat register: “A sheet covered her body up to her shoulders, hiding her hands. She looked like a small mummy.” Driving back to town from the hospital, Ernaux realizes that “[s]he will never be alive anywhere in the world again.” (The moving precision of that “anywhere”!) Her thoughts on her working-class mother all those years ago exhibit how Ernaux honed her style: “[S]he spent all day selling milk and potatoes so that I could sit in a lecture hall and learn about Plato.”

Ernaux devoted another book to her mother’s demise, I Remain in Darkness (1997), titled after the last note she scribbled before losing her lucidity. Reading detailed depictions of her mother’s dementia is unnerving — and I wondered whether Ernaux had abused her authorial license. Yet she faces her own guilt, her feeling of being “torn between my writing, which portrayed her as a young woman moving toward the world, and the reality of hospital visits, which reminded me of her inexorable decline.” Shocking moments fill the book, including finding a “human turd” in a drawer by her mother’s bedside. During this sad time, she’s consoled by the idea that at least she was there with her mother in her direst time of need. This new portrait allows Ernaux to unite with the stream of time: “[N]ow I belong in a chain, my life is part of a process that will outlive me.”

In Exteriors (1993), a “journal of exteriors” she kept until 1992, Ernaux took a different path. “[N]either reportage nor a study of urban sociology, but an attempt to convey the reality of an epoch” is how she describes her snapshots, which explore a community’s routines, allowing her to disappear in Paris’s exteriors. “[A] hypermarket can provide just as much meaning and human truth as a concert hall,” she writes, and among her book’s most curious scenes is one about people queueing in front of a cash machine. “A confessional without curtains” is how she describes it. Exteriors concludes with an epiphany: “So it is outside my own life that my past existence lies: in passengers commuting on the subway or the RER; in shoppers glimpsed on escalators at Auchan or in the Galeries Lafayette; in complete strangers who cannot know that they possess part of my story; in faces and bodies which I shall never see again.”

Shame (1997) tackles a traumatic childhood memory: just before Ernaux turned 12, her father tried to kill her mother. Once she committed that story to paper, Ernaux felt it was an “ordinary incident, far more common among families than I had originally thought,” and concluded: “It may be that narrative, any kind of narrative, lends normality to people’s deeds, including the most dramatic ones.” The episode marked her childhood’s finale, kickstarting an “era when I shall never cease to feel ashamed.” Now, her self-set task was to “single out part of that summer period, in the manner of a historian.” In doing so, Ernaux rejected the impulse to romanticize events; instead, she would carry out “an ethnological study of myself.”

Shameful sex and a secretive pregnancy lay at the center of Happening (2000), wherein Ernaux immerses herself in a painful part of her life, endeavoring to revisit each image “until I feel that I have physically bonded with it, until a few words spring forth, of which I can say, ‘yes, that’s it.’” Her narrative says little about the father; he swiftly vanishes, and Ernaux faces a coalition of other men trying to trick her into delivering the child. Attempts to return to her routine of attending classes and working at the library fail. In this journey, Ernaux has no idea “where my writing will take me.” Her handling of the aftermath of her abortion, though, is beautiful, and reads poignantly today, particularly in the United States, where that right has partly perished: “It was a cold, sunny month of February. I walked back into a different world. Cars, strangers’ faces, trays of food in the canteen — everything I saw was vibrant with intention.”

The Possession (2002), one of Ernaux’s books I like best, details an affair with W., a man the author left several months earlier after six years together. “The first thing I did after waking up,” she recalls, “was grab his cock — stiff with sleep — and hold still, as if hanging onto a branch. I’d think, ‘as long as I’m holding this, I am not lost in the world.’” Now another woman holds that cock, and The Possession embodies Ernaux’s obsession with her. Anyone who has experienced jealousy will find the scene familiar: “All of my thoughts passed through her. This woman filled my head, my chest, and my gut; she was always with me, she took control of my emotions.” Her rival’s omnipresence provides Ernaux’s life with a new intensity: “[I]t held me in a state of constant, feverish activity. I was, in both senses of the word, possessed.”

But it was The Years (2008) that earned Ernaux the reputation she deserved in French literature. The book synthesized her upbringing with public history in a groundbreaking way: addressing herself in the third person, Ernaux talks from the purview of a collective we, and her sociological document has a powerful punch, both emotional and political. “Advertising provided models for how to live, behave, and furnish the home” in the “consumer society” whose birth she witnessed. Fruit-flavored Évian water, Barbie dolls, Cadbury cookies, and Nutella enter French life; her generation reads Charlie Hebdo and Libération, sustaining their “belief in belonging to a community of revolutionary pleasure.” In those years, “class struggle” and “political commitment” became words of the past that elicit “smiles of commiseration.” Performance, challenge, and profit replace them. This was, she notes, “the age of the silver-tongued,” and she writes snappily about how people “applauded the cynicism of Michel Houellebecq.”

Yet these were happy years for Ernaux: her husband was gone after their divorce, her mother died after a traumatizing bout of dementia, and her sons lived elsewhere. “Serenely she notes this dispossession as an inevitable part of her trajectory. When she shops for groceries at Auchan, she no longer needs a trolley; a basket is enough.” This portrait of herself in midlife coincides with her search for a self outside of history and will likely be remembered as Ernaux’s masterpiece.

Ernaux returned to her miniatures in A Girl’s Story (2016), which investigates an incident at a summer camp in 1958. Riddled with anxiety while writing it, she feared reaching the end of her life and not being able to write as much as she could. “The time that lies ahead of me grows shorter. There will inevitably be a last book, as there is always a last lover, a last spring, but no sign by which to know them.” She’s haunted by the idea that she “could die without ever having written about ‘the girl of ’58,’ as I very soon began to call her.” Only this subject seems vital to her; the thought of just enjoying life becomes unbearable. Despite the “staggering imbalance” between the influence of “H” on her life and “the nothingness of my presence in his,” she doesn’t envy him. After all, “I’m the one who is writing.” It’s the attitude we’ll see resurface in her books on the Soviet diplomat.

Ernaux first told the story of her fling with the Soviet diplomat in Simple Passion (1991), published at a time when French intellectuals watched hardcore porn on Canal Plus: “[H]undreds of generations have gone by, and it is only now that we get to see this, a man’s penis and a woman’s vagina coming together, the sperm — something we couldn’t take in without almost dying of shame has become as easy to watch as a handshake.” Ernaux realized that “writing should aim to do the same, to replicate the feeling of witnessing sexual intercourse, that feeling of anxiety and stupefaction, a suspension of moral judgment.”

But Simple Passion isn’t pornographic — it’s Proustian. It tells of a torturous affair wherein she first deduced “from certain signs that he experienced the same passion as me.” Other signs signaled that she was but a mistress for him, “an ass.” The obsession turned her into a detective: she could no longer go away on holiday; at La Badia, Florence, where Dante met Beatrice, she felt ecstatic only because “of my story, which would come to resemble them one day.” She returns to a hotel room in Venice she had stayed in just before meeting the diplomat so that history could somehow repeat itself for her. She agrees to attend a seminar in Copenhagen just for the chance it provides her to send him news of her stay: “On the plane, on the way back, I reflected that I had traveled to Denmark simply to send a postcard to a man.”

At the end of A Simple Passion, we find Ernaux determined to be “through with innocence.” Yet a year later, in February 1991, she returns to the manuscript, for the diplomat has returned: “On the first Sunday of the war, in the evening, the phone rang. A’s voice. For a split second, I was seized with panic. I kept repeating his name, crying.” His return allows Ernaux to “approach the frontier separating me from others,” and without knowing it, he brings her closer to the world. All Ernaux did was translate him into “words he will probably never read, which are not intended for him.” Hers was an “offering of a sort, bequeathed to others.”

Getting Lost is Ernaux’s second offering to these lost years. Between 1988 and 1990, she wrote prefaces for books, corrected proofs of English translations, attended banquets with the likes of François Mitterrand and then Prince Charles, appeared on Apostrophes (Bernard Pivot’s legendary literature talk show), and was seemingly flourishing. In fact, she was imploding, experiencing a loss similar to her abortion and her mother’s death. The only place she honestly wrote in those years was in the journal she had kept since adolescence. “It was a way of enduring the wait until we saw each other again,” Ernaux recalls in the book’s introduction. “Most of all, it was a way to save life, to save from nothingness the thing that most resembles it.”

Ernaux’s diaries begin with her first hookup with S in Russia in 1988. As the Soviet cultural attaché in Paris, S organized an event for a small group of French writers (“useful idiots,” as they used to call them, who were to praise Soviet socialism’s beauties back home). When left alone, S and Ernaux throw themselves at each other. “My back, pressed against the wall, switches the light off and on. I have to move aside. I drop my raincoat, handbag, suit jacket. S turns off the light.” With this, a night begins, which she “experience[s] with absolute intensity.” They meet again on the sleeper train to Moscow, kissing at the back of the carriage. Flying home, Ernaux “trie[s] to reconstruct events, but they tend to elude me, as if something had happened outside my consciousness.”

S is a metonym of Russian culture. Which author could resist visiting Leningrad, entering Dostoevsky’s house, wandering the Hermitage, “crossing a bridge over the Neva,” and having dinner at the Hotel Karelia? Why Ernaux was attracted to a crumbling regime’s apparatchik is therefore easily explainable.

Yet the attraction of being close to power has an equally problematic aspect. A member of the Communist Party since 1979, S is among its finest servants. Thinking of him, Ernaux remembers her first arrival in Moscow in 1981 and seeing a tall, young Russian soldier before bursting into tears. She was “overwhelmed to be there, in that near-imaginary country. Now it is a little as if I were making love with that Russian soldier and all the emotion of seven years ago had led to S.” S is a madeleine of sorts that ignites remembrance. He’s also a walking contradiction, as “he talks about his wife, how they met, and the necessary restrictions on morality in the USSR, and minutes later, begs to go upstairs so we can make love.”

Despite their flaws, Ernaux is concerned for the future of S and the Soviets: “His life is truly precious to me, and I already ache for Russia, and for what most probably will happen there in the years to come, appalling upheavals. What will become of him?” When she watches a 1956 Soviet film one day, she thinks that understanding S would also mean “to understand the women in kerchiefs who lived at the same time I was dancing to rock ’n’ roll, the communist organization, etc.”

Then he ghosts her. She’s condemned to live in the hell of unknowing. She had, she writes, merely “glimpsed something I could never have imagined before, because it had never been embodied, in a face, words, a pair of hands: the communist ideal which rallied men and women in Leningrad, in Stalingrad, and was passed on to that blond green-eyed boy.”

Was S a KGB member? This is Ernaux’s answer: “S himself wasn’t with the KGB, it seemed to me (lack of evidence goes with the territory). How often might I have explained in terms of affairs with other women things which were, in fact, connected to the (always secret) politico-diplomatic context of the Soviet Union?” Still, she’s aware that her “only true rival” during the relationship was his “‘career,’ a position so difficult to keep in these times of perestroika.”

Yet the person for whom she has this “all-consuming hunger” is not an intellectual but an adorer of “fancy cars,” someone who “likes to ‘make a splash.’” Her role in the relationship is “the writer, the foreigner, the whore — the free woman too.” None of which helps cool her desire for him, of course.

Then there’s the sex, which Ernaux details in anatomical detail: “Tonight, anal sex for the first time. Good that the first time was with him. It’s true that a young man in one’s bed takes the mind off time and age.” Sex with S is demanding — yet it is all she can afford to do. “My mouth, face, and sex are ravaged. I don’t make love like a writer, that is, in a removed way, or while thinking, ‘I can use this in a book.’ I always make love as if it were the last time (and who’s to say it isn’t?), simply as a living being.” At times, intercourse “descen[ds] into sadomasochism, but gentle, without violence,” and comprises a “combination of sodomy and ‘normal’ sex — bruised all over, at one point, I thought I was torn.” One day, she spills “champagne on his penis, quite sure that no one’s ever done anything like that to him.” She tells him: “Anywhere, anytime, ask me anything, and I’ll give it to you, I’ll do it for you.”

Reading these diaries during a week of humid weather, I felt more unsettled than I did reading the skeletal Simple Passion in one sitting. These diary snippets weave a terrifying dynamic between S’s presence and absence and seem to go on forever, suffocating the reader. “I can no longer picture his face when he’s not here,” she scribbles in a moment of loneliness. And when she’s with S, “[h]e has another face, so close, so irrefutable, like a double.” She ponders what to do with all her time with this man, weighing the possibilities of alchemizing him into art. In a parenthesis, she quotes Michel Foucault, the great philosopher of bodily discipline: “[T]he highest good is to make one’s life a work of art.” Still, secretly, she is disdainful and spiteful and hopes to get rid of S, to “write off” his memories.

Then the Berlin Wall collapses, shattering her world. S is called back to Moscow:

History again becomes unpredictable. […] A sense of encroaching chaos, and reaction from Russia cannot be ruled out. S will be part of that, obviously, his father having been decorated by Stalin! I fear the reunification of Germany (again, a fear determined by the past), as if it could bring on a third world war.

A painful farewell ensues. Blowing her a kiss, he promises: “I’ll be back,” to which she snaps: “I’ll be old.” Yet, he swears, “You’ll never be old for me,” and she muses: “I’ll try not to get old.” S’s total absence turns out to be too much to bear, reminiscent of her mother’s death: “I can understand families of the missing never believing they’re dead.” During the night, wide awake with anxiety, she experiences, stunningly, “[t]he immediate desire to have myself screened for AIDS. Like a desire for death, and love: ‘at least he’ll have left me that.’”

She fantasizes about him coming back. He’ll “have gotten fatter, and drink more whiskey. There’ll be little broken blood vessels over his cheekbones.” She knows he didn’t love her as much as she did him, yet her dreams refuse to perish. When that excruciating year, 1989, finally ends, Ernaux understands that everything she had wished for at its beginning “more or less came true, except I didn’t know the price I’d have to pay.”

Then, 1990 arrives — a new decade. On January 1, she wonders whether it will change her life, as 1960 and 1970 did: “To ask myself the question is to express the desire that it will. But the unknown, uncontrollable upheaval does not inspire me overmuch.” She commits herself to a new book. And her second wish? It is, of course, “to hear from S, in January, and see him again in 1990, in the East or the West. Really, the greatest joy of all would be a conjunction of love and History, a Soviet (r)evolution in which we could meet again.”

By this point, we surmise that S will never cease to exist in Ernaux’s life. She accepts his absence as now permanent. And how will her story and History evolve over the next few years? She decides those will be the years when she’ll have to “resist (physical decline) and testify (writing).” Still, her determination to get back to solitude quickly fails. Reading Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler on the train back from Marseille one day, a passage fills her with a “burning desire, an incredible longing to make love, though since S left, I’ve been all but frozen.”

S has left her and taken his part in their shared story with him. There’s nothing she can do about that. She comes across a beautiful passage by Borges: “Century follows century, and things happen only in the present. There are countless men in the air, on land and at sea, and all that really happens happens to me.” That’s exactly how she feels, as the present time has come to mean the same thing: “It is me, me … It’s been obvious all along.” Still, if losing a man, as she reflects at one point, is to “age several years in one fell swoop, grow older by all the time that did not pass when he was there, and the imagined years to come,” then writing, the only consolation, can still wield a magical power, that of restoring lost time.

And so, Getting Lost ends on an empowering note. For the first time since she last saw S, Ernaux wakes up “with an inexplicable feeling of happiness.” She knows her happiness is unfounded, but she knows something else, too. It’s the catalyst that drives all the works of this peerless self-portraitist: “There is this need I have to write something that puts me in danger, like a cellar door that opens and must be entered, come what may.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Kaya Genç is the author of three books from Bloomsbury Publishing: The Lion and the Nightingale (2019), Under the Shadow (2016), and An Istanbul Anthology (2015). He has contributed to the world’s leading journals and newspapers, including two front page stories in The New York Times, cover stories in The New York Review of Books, Foreign Affairs, and The Times Literary Supplement, and essays and articles in The New Yorker, The Nation, The Paris Review, The Guardian, The Financial Times, The New Statesman, The New Republic, Time, Newsweek, and the London Review of Books. The Atlantic picked Kaya’s writings for the magazine’s “best works of journalism in 2014” list. A critic for Artforum and Art in America, and a contributing editor at Index on Censorship, Kaya gave lectures at venues including the Royal Anthropological Institute, and appeared live on flagship programs including the Leonard Lopate Show on WNYC and BBC’s Start the Week. He has been a speaker at Edinburgh, Jaipur, and Ways with Words book festivals, and holds a PhD in English literature. Kaya is the Istanbul correspondent of the Los Angeles Review of Books.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Intimate Portrait of a Generation: Annie Ernaux’s “The Years”

Azarin Sadegh reviews Annie Ernaux's memoir, recently translated by Alison L. Strayer.

Unsolved Problems: Rachel Kushner on Marguerite Duras

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!