All Dogs Go to Heaven: David Bentley Hart’s Canine Panpsychism

Ed Simon reviews “Roland in Moonlight,” the recently published book by David Bentley Hart.

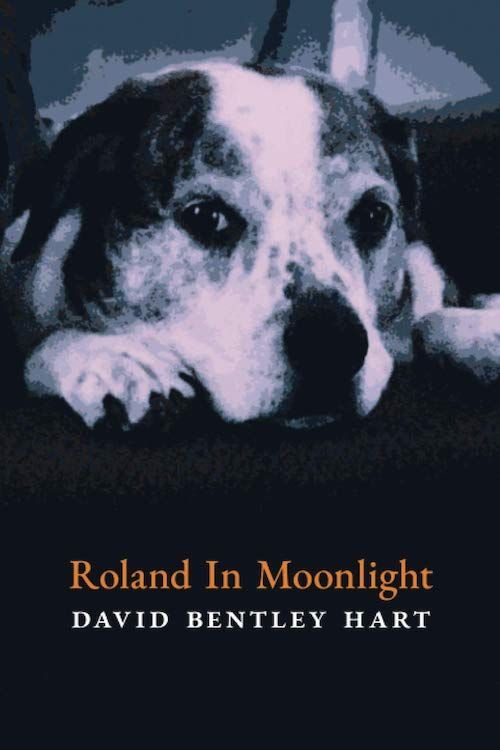

Roland in Moonlight by David Bentley Hart. Angelico Press. 386 pages.

INCLUDED AMONG THE great literary felines would be the ninth-century Pangur Bán, written about by an Irish monk of Reichenau Abbey who enthused that his pet was “the master of the work which he does every day”; the witch-queen Grimalkin in William Baldwin’s 1561 novel, Beware the Cat, where “birds and beasts” have “the power of reason”; Montaigne’s kitten of which he asked, “When I play with my cat, how do I know she is not playing with me?”; Dr. Johnson’s beloved Hodge, of whom Boswell wrote that the great lexicographer “used to go out and buy oysters [for him], lest the servants having that trouble should take a dislike to the poor creature”; and of course T. S. Eliot’s splendiferous Mr. Mistoffelees.

By my estimation, however, no cat is quite as divine as Jeoffry, the subject of Christopher Smart’s brilliant, beautiful, and exceedingly odd 1763 masterpiece, Jubilate Agno, written while the English poet was convalescing in St. Luke’s Hospital for Lunatics. Smart notes that his only companion, Jeoffry, is the “servant of the Living God duly and daily serving him. […] For he keeps the Lord’s watch in the night against the adversary. / For he counteracts the Devil, who is death, by brisking about the life. / For in his morning orisons he loves the sun and the sun loves him. / For he is of the Tribe of Tiger.”

Decades before William Blake and a century before Walt Whitman, Smart had unshackled poetry from its formal constraints, though with little of the self-seriousness of the former and none of the self-absorption of the latter. To interpret the poem as only a trifle is to miss something. For when Smart describes Jeoffry as an embodiment of the sacred, he is completely serious, since “he is a mixture of gravity and waggery. / For he knows that God is his Saviour.”

I’ve never been much of a cat person. Which isn’t to say that I’m not convinced by Smart — the opposite is true, actually. It’s just that I’m so fully a canine partisan that I can’t break my loyalty. Literature and philosophy have a dearth of dogs that rise to Jeoffry’s level, or even to that of Montaigne’s playful cat. As charming and instructive though they may be, L. Frank Baum’s Toto in The Wizard of Oz and Jack London’s Buck in Call of the Wild aren’t ones for whom “God has blessed him in the variety of his movements.” Felines were worshiped by the priests of Bastet, but what cat in ancient Egypt could match the loyalty of Argos in the Odyssey? Or the drunken wit of the white terrier Snowy from the Belgian comics writer Hergé’s Tintin? Or even the sheer determination of Lassie?

Those are all admirable mutts, but they’re not divine. An injustice. Human evolution since the Neolithic period owes everything to those lean, hungry, and estimably brave wolves that first approached bands of hunters cooking their food upon the frozen steppes. Now David Bentley Hart, arguably the most significant American theologian since Paul Tillich, has rectified this absence by crafting an “inscrutable and mighty soul” in the form of the eponymous central character of Roland in the Moonlight, an SPCA adopted “mix of breeds,” including parentage from a Boston terrier and from “some kind of hound, perhaps bluetick.” A character, it should be said, that with his “particolored collage of abstract patterns, patches, and shades: a mottled, speckled, and brinded coat of white, black, brown, light auburn, and gray; two dark, glossily drooping ears parenthesizing a gentle and pensive face [and] a gleaming coal-black nose” looks very much like the Roland who accompanies Hart’s author picture, a dog who pads around the University of Notre Dame professor’s South Bend home.

Both Roland and Jeoffry are creatures of God who are “tenacious of his point,” but only the former is actually able to express his point. For you see, Roland is a speaking canine, or as his guardian says to him, “You’re a very unusual dog.” It should be added that this is a very unusual book, but that that isn’t to its detriment. To describe what exactly Roland in the Moonlight is about is difficult; better to deploy the via negativa and emphasize that this is not a fairy tale or a story for children, unless you’re raising kids who are able to parse competing philosophical theories of mind, Christian esotericism, Vedic philosophy, kabbalah, Gnosticism, arguments against materialist metaphysics, epistemology, Japanese aesthetics, Chinese classical poetry, Homeric epics, and neo-Pagan modernism, not to mention contemporary politics.

What Hart has produced is a Platonic dialogue in the form of a beast-fable, wherein the author and his erudite canine grapple with the disenchantments of modernity, the reductionism of physicalist theories of mind, and the future potential for a human culture that’s clearly, to most of us, in its death throes. If all of this sounds eccentric — and Roland in the Moonlight is gloriously eccentric — that’s to lose sight of Hart’s central concern. As Roland says, “So what you need to do now […] is raise the deeper question: not, say, ‘Can animals be saved?’ but ‘Can persons be?’”

That may seem strange coming from the theologian who I’ve already claimed to be the most important since Tillich, but it shouldn’t be, because part of what makes Hart such an idiosyncratic, heterodox, and wonderfully heretical thinker is that he’s able to pose such an inquiry. Not only to pose it, but to answer it, and in the process diagnose that which bedevils post-modernity and late capitalism.

Author of thousands of essays, reviews, and papers, as well as 15 books including Atheist Delusions: The Christian Revolution and Its Fashionable Enemies, The Experience of God: Being, Consciousness, Bliss, as well as That All Shall Be Saved: Heaven, Hell, and Universal Salvation, not to mention an immaculate translation of the New Testament, Hart is often difficult for some people to categorize. What’s agreed upon is that he’s wide-ranging and deeply read in his seemingly limitless interests, and loquacious in his refreshingly baroque prose style; the rare theologian who can poetically invoke the “glow of a gibbous moon set high in the sky, shining like a polished white opal on a bed of indigo velvet” or how a “strong breeze was stirring the leaves in the high trees enclosing the grounds, and was shaking the branches of the lilac and oleander bushes bordering the path to the door […] ripples of silver […] coursing continually through the lawn’s broad blades of fescue grass.”

Matthew Walther, in The Washington Free Beacon, described Hart as the “Prospero of Theologians” and “our greatest living essayist” — an evaluation with merit from a site I often disagree with. Because Hart used to write a column for the conservative Catholic journal First Things, and because his aesthetics are High Church and his writing is Chestertonian, some have assumed Hart to be politically conservative. Such fallacious reasoning should have been put to rest years ago, after Hart publicly expressed his commitment to left-wing economics and his membership in the Democratic Socialists of America, not to mention his footnotes for the New Testament which make Christ’s radical beliefs clear.

Roland in the Moonlight should dissuade anyone that tweediness implies revanchism, as Hart diagnoses contemporary conservatism as a “pathetic clinging to nostalgias and resentments, a fixation on the transient [from those] who equate social change with a loss of self,” a “self-serious and spiteful biliousness” that is nothing more than the “long, loud whine of the psychologically convalescent.” Even more deliciously, Hart condemns the former president whom First Things endorsed as a “slobbering, slouching, whining, brutish, tumid, psychopathic simpleton” who “drowned civic life in a ceaseless stream of atrocities, pollutions, perversions, cruelties, lies, and violence.”

So no, Hart isn’t a conservative. If his politics are clear then it’s also true that the diversity of his examples and the subtlety of his thought sometimes pushed people to classify him as theologically traditional, which was even more of an egregious error. Rod Dreher — who only seems to share Hart’s Orthodox faith — wrote generously in The American Conservative that the latter “has a way of talking about God that makes the subject seem fresh and alluring.” Because John Milbank had such a formative influence on the thinker, Hart is sometimes classified with “radical orthodoxy,” but though the affinities are clear, the theologian seems more radical than orthodox to really be classified as such. In my own limited experience, I’ve seen Hart embraced by the so-called “Emerging Church” movement, “post-evangelicals” who are now “deconstructing” their previous faith, but too much of the Hosana and the hand clapping remains. It would be bizarre to designate the theologian himself as part of this group. Hart is, in many ways, a movement unto himself.

The clearest indication of Hart’s daring is his That All Shall Be Saved, which is a humane and convincing argument for Christian universalism against the doctrine of Hell (for those who care about such things). “As far as I am concerned,” Hart wrote in that book,

anyone who hopes for the universal reconciliation of all creatures with God must already believe that this would be the best possible ending to the Christian story; and such a person has then no excuse for imagining that God could bring any but the best possible ending to pass without thereby being in some sense a failed creator.

You don’t use the waters of heaven to quench the fires of hell without singing the feathers of doctrinaire Thomists, Calvinists, and Arminians, who predictably reacted as if Hart belonged in that nonexistent place. First Things ran two hatchet-job denunciations of That All Shall Be Saved, with Michael McClymond sternly intoning in his essay that “Universalism is hopefulness run amok, the opiate of the theologians.” Which is what’s so subversively brilliant about Roland. For Hart makes an argument in this latest book that’s far more radical than the universalism of salvation in That All Shall Be Saved, and that is a universalism of doctrine. To my delight, and to the horror of the traditionalists, Hart unequivocally reveals himself to be an ecumenical post-Christian pagan, for whom, as his titular dog says, “the whole of the world was alive at the innermost, most primordial level, and the deepest, most original source of all things is consciousness.”

A talking beast may be a stumbling block to Christians and foolishness to atheists, but for the pagan in pastoral paradise, such divine creatures were merely nodes in that Great Chain of Being. Speaking animals have a venerable history in both Western and Eastern literature, imparting wisdom and connecting humanity to the natural world: the Hindu monkey-god Hanuman in the Ramayana and Balaam’s donkey in the Book of Numbers; the trickster of Medieval German folktales Reynard the Fox and his cousin among the American Indians Coyote; Beatrix Potter’s delightful Peter Rabbit and the denizens of the sylvan meadows of Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, including Mole, Rat, Badger, and Toad (Hart’s epigraph comes from the last).

Roland serves a purpose not unlike the titular Ishmael in Daniel Quinn’s philosophical novel, a gorilla who discourses on ecological sustainability and the sacredness of nature. After all, Roland voices positions that we can attribute to Hart as surely as Socrates spoke the sentiments of Plato. Hart’s use of Roland is more sophisticated than this, however. To begin with, Roland might discourse on Heidegger and Freud, but he also enjoys bacon treats, rawhide bones, and waxing olfactory about “subtle shadings of redolence […] of scent that overflows the very pith of things, the great floods and the small tenuous rivulets of pure fragrance.”

The eponymous character’s identity is not incidental. Hart hasn’t crafted a cute talking dog just to express his own positions; rather, it’s crucial in and of itself that his interlocutor is a dog, because when the writer argues that it’s consciousness all the way down, he means it. What this book evokes is a “world that speaks […] a world that feels […] that’s conscious and alive. For communion.” Roland in the Moonlight’s narrative and its structure is thus inseparable from Hart’s argument.

Roland in the Moonlight is a book where Hart very clearly enjoys himself as he’s writing, but his intentions are sober and serious. What Hart argues for is a beautiful and incendiary amendment to the Christian experiment. His central claim is that the cold and senseless mechanistic philosophy which is a staple of our era has pushed the disenchantments that began five centuries ago to our current precipice of ecological collapse, that humanity has been cleaved from the natural world because of belief in a cumbersome mind-body duality, and that our only possibility of redemption is in idealist panpsychism which sees consciousness as instrumental. “Modern thinking […] reduces myth to pure fantasy,” Roland says,

But you can’t suppress those other worlds forever, or even completely. They still wait there, pressing through — at least, till the last shaman or mad visionary, the last blessed lunatic, the last Blake or Kit Smart, has turned to dust. The last terrier, the last dolphin, the last grey parrot. The last octopus.

(You’ll note the mention of our dear poet Christopher in there.)

As a not-so-modest suggestion, Hart proposes a new perennialism in that great neo-Platonic tradition from Marsilio Ficino to Aldous Huxley, so that “the only way your kind can hope to find its way back to the theophanic cosmos” is to see the various faiths, “whether it’s Christianity or Hinduism or Australian Aboriginal spirituality or Sioux or Yoruba visionary wisdom” as being deeply and fundamentally true, “to believe all of it.”

The most crucial virtue for an intellectual pugilist is to clearly know who his — and our — enemies happen to be. Roland explains that if we’re to survive the Anthropocene, we must break the “hold of these counterfeit forms of faith […] these shriveled positivisms and prejudices camouflaged as true belief.” The first of these two idols is the error which took the idea of mechanization — initially a conceit for the smooth operation of the stupendously successful empiricism of the scientific method — for a totalizing metaphysic, with the result being the cold materialism that reduces the soul to the brain, human beings to commodities, and nature to exploitable resources.

Modern religion does nothing to counteract such positivism. As Hart writes, the “fiercest forms of faith in the modern world are actually just inverted forms of faithlessness — forms of desperation masquerading as faith.” Namechecking Tridentine Catholicism and Protestant Fundamentalism, Hart condemns these zealotries as “manifestations of a morbidly impoverished power of belief, a faith wasted away by inanition and hardened by desiccation, and of a frantic attempt to hold on to relics of remains that one mistakes for living possibilities.” What Roland — or Hart — rejects is the estrangement between mind and soul, matter and spirit, heaven and earth, and an understanding that the only redemptive and emancipatory pose for a culture on the verge of environmental apocalypse is the idea that consciousness permeates all of reality.

The talking of the dog isn’t a conceit — there’s something literal here, for Hart is saying that all of nature speaks if we’d only listen, if we’d only stop letting the dun of all these infernal machines drown that music out. Ours is an age where “[n]othing is sacred in itself, no mystery is honored,” and it’s been this way for a while, where the “reservoir of purely material resources is to be exploited and despoiled and then corrupted with toxins and microplastics and every imaginable chemical and synthetic pollution.” What dogs offer us isn’t just their guardianship, or companionship, or loyalty, but the perspective of a radically different consciousness, an intimation of that Eden which we left behind when there was a more seamless continuity between the human and the natural.

No animal has been by our sides longer than dogs; for 15 millennia they have trotted by us, kept us warm on cold nights, barked at those who threaten us. Our partnership with these creatures predates science, religion, even agriculture. The question of who domesticated whom is just one of perspective. Maybe it’s more correct to say that canines were tamed but humans are fallen; for the mental perspective of a Pleistocene wolf, the guard dog immortalized in the floor mosaic of Pompei, or the lap dog sitting in Diego Velázquez’s Portrait of Prince Philip Prospero are, despite their diversity, unified in a doggy perspective that directly connects to the thing-in-itself in a way that we no longer can. After all, Siddhartha himself understood that dogs have Buddha-nature.

“As a dog,” Roland is “immune both by nature and by culture of the barbarism of mechanistic thinking,” for he is not condemned as we are. The dog’s example has always been of divinity, a manner of being in the world that is fully present, that revels in simple ecstasies. Anyone who has ever loved a dog, and been fortunate enough to be loved in return, understands that much. What Roland in the Moonlight supposes is that if we were capable of such love all the time it might just save the world. As Hart writes, “[F]or a dog every day is so full of the richness of sheer sensibility — so many reflections, so many scents, so many thrills of vitality, such deep communion with the invincible animal energy of life — that ten years is an age.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Ed Simon is the editor of Belt Magazine, a staff writer for Lit Hub, and an emeritus staff writer at The Millions. He is a frequent contributor at several different sites including The Atlantic, The Paris Review Daily, Aeon, Jacobin, The Washington Post, The New York Times, Killing the Buddha, Salon, The Public Domain Review, Atlas Obscura, JSTOR Daily, and Newsweek. He is also the author of several books, including Devil’s Contract: The History of the Faustian Bargain, which will be released in July 2024. He holds a PhD in English from Lehigh University and an MA in literary and cultural studies from Carnegie Mellon University.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Doubting Thomas: On Peter Manseau’s “The Jefferson Bible”

Ed Simon reviews Peter Manseau’s “The Jefferson Bible.”

Not to Be Cynical, But …

Ed Simon evaluates "Cynicism," the recent book from Ansgar Allen.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!