After the Leap: Marriage and Philosophy in George Eliot and Søren Kierkegaard

Clare Carlisle analyzes the theme of marriage in the life and work of two great 19th-century thinkers and writers, George Eliot and Søren Kierkegaard.

GEORGE ELIOT and Søren Kierkegaard were born in the same decade, six years apart: Kierkegaard in a smart townhouse in the center of Copenhagen in 1813, Mary Ann Evans—George Eliot’s given name—in humbler circumstances in rural Warwickshire, England’s “Midlands,” in 1819. They both became philosophers. And they both wrote remarkable works animated by the marriage question—a question that continues to transgress the dubious boundary between philosophy and life. At a time when this boundary was being fixed and entrenched by an increasingly professionalized, specialized academic culture, Eliot and Kierkegaard leapt over it, bringing profound ideas to wide readerships. Some of their most devoted contemporary readers were women and working men—readers with no access to higher education, who found in these books the intellectual and spiritual sustenance they craved.

Academia boomed during the 19th century. New universities opened in cities across Europe and the United States, starting with Berlin in 1810. New academic disciplines were established: biology, sociology, geography, history, biblical studies, anthropology. Yet Kierkegaard and Eliot philosophized outside the university, for different reasons; they both voraciously pursued the life of the mind, while feeling deeply ambivalent towards it. After 10 years as a student, Kierkegaard was thoroughly disaffected by the systematic, scientific (or quasi-scientific) treatises and lectures that had become the gold standard of serious thought. His defiant, experimental works ridiculed salaried professors while tearing philosophy out of their hands. Marriages, engagements, seductions, and unrequited loves were Kierkegaard’s subject matter. “A love affair is always an instructive theme regarding what it means to exist,” he wrote at the age of 33, still struggling to come to terms with the failure of his own love affair five years earlier.

Eliot would have loved to study philosophy and theology, like Kierkegaard, but British universities remained closed to women until the late 1860s. She had to teach herself these subjects, along with history, science, political theory, and classical languages and literature. While Kierkegaard trained his philosophical “microscope” on the human heart (as one contemporary put it), Eliot immersed herself in scholarly labors, translating German works by David Strauss and Ludwig Feuerbach and planning her own treatises. But she, too, soon turned her attention to the human heart. As her own love life defied convention, her novels drew deep truths from the intense existential dramas played out in ordinary domestic interiors, hidden behind closed doors.

¤

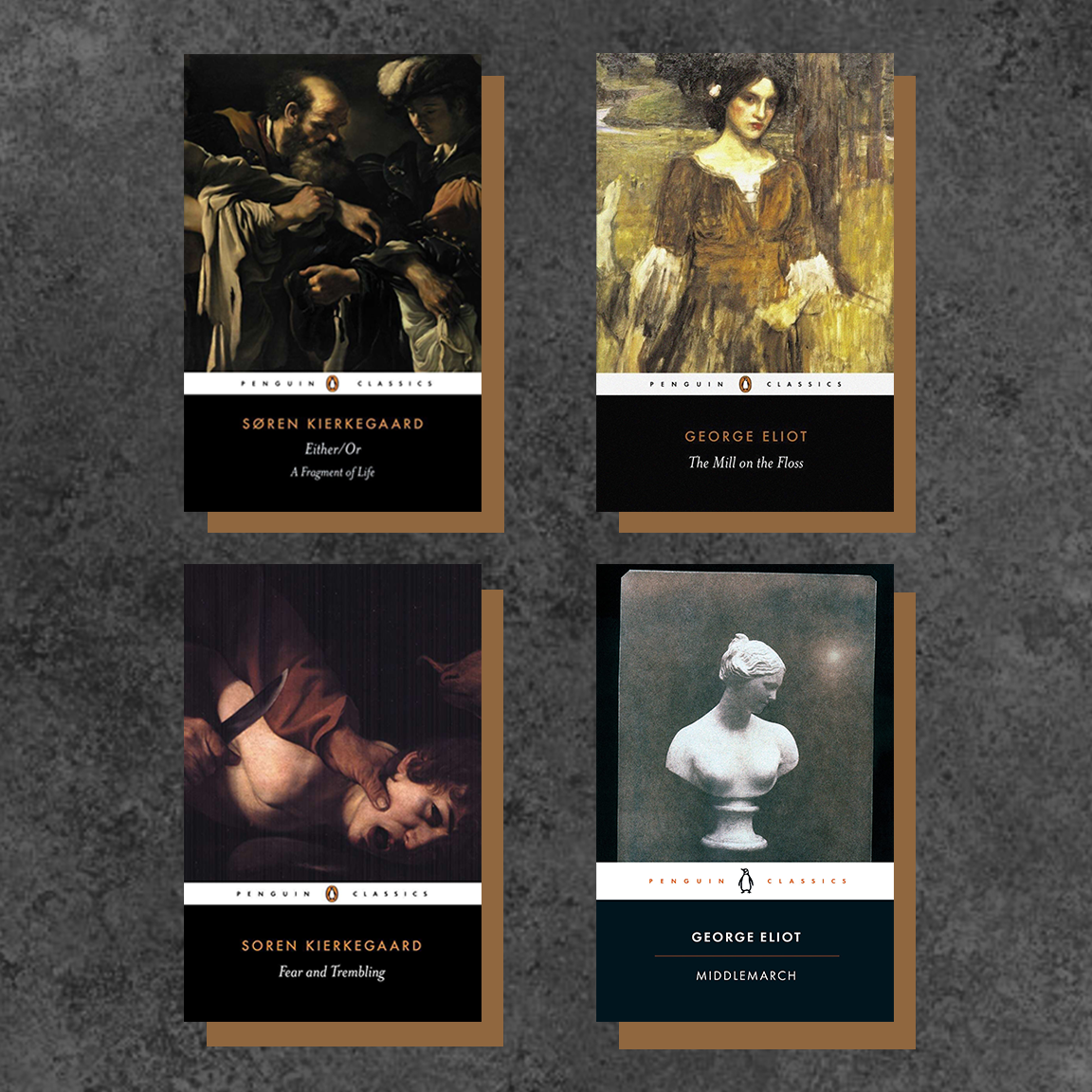

Marriage was the defining question of Kierkegaard’s life. As for many of us, his formative experience of his parents’ marriage was not straightforward. His mother was his father’s second wife, previously the housemaid; their first child was conceived before they married. Kierkegaard’s philosophical career began when he broke up with his fiancée, Regine Olsen, in 1841: his first book, Either/Or (1843), emerged from that engagement crisis. There, marriage is the archetypal existential choice, in which we not only choose another person but also choose ourselves. We choose to be a wife or husband, a role both private and public. And we choose to be the person we will become in this specific relationship. This is a choice of something largely unknown since both partners are growing and changing. Their untold fortunes will affect one another deeply: for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health.

Marriage is, in other words, a leap of faith. “[A] flying leap into infinite space,” as Jane Carlyle warned a young woman contemplating this marital leap, 30 years into Jane’s own marriage to the intellectual giant Thomas Carlyle, a very difficult man. “If I had had faith, I would have married Regine,” Kierkegaard wrote in 1843, just after Either/Or was published. That same year, he wrote two more books, Fear and Trembling and Repetition. Both reprised the themes of his relationship crisis; Repetition actually dramatized a broken engagement.

Either/Or is divided into two halves, authored by two different pseudonyms. The first, a nihilistic, dilettantish young man, refuses to take choice seriously: “Marry or do not marry, you will regret it either way.” Either/Or’s second author, a happily married judge named William, defends marriage on both aesthetic and moral grounds. “[T]o choose,” he insists, “is an intrinsic and stringent term for the ethical.”

We might read Judge William’s words as an admonition to Kierkegaard himself. He failed to marry, failed to choose, failed to leap. But of course, he could not avoid choosing. Breaking his engagement to Regine was a momentous leap into a new life. “I am […] born by the fact that I choose myself,” declares Judge William, and this applies to Kierkegaard’s decision to separate from Regine as much as it would apply if he had married her. In his crisis of faith, Kierkegaard was born as a philosopher.

When Eliot was in her mid-thirties, just before she began to write fiction, she made a bold leap into a public partnership with George Henry Lewes: journalist, philosopher, and married man. Lewes was already disreputable. He was illegitimate, self-educated, and a notoriously free-loving atheist whose wife had borne him three sons before having more children by his best friend. In 1854, after a few months of seeing each other in secret, Eliot and Lewes traveled to Germany together, causing a great scandal back in England. When her family found out, they cut her off.

Eliot’s decision to live openly with her married lover, like Kierkegaard’s decision to jilt Regine, proved to be inseparable from her formation as an author. Under Lewes’s influence, she began to translate Baruch Spinoza’s Ethics (1677) during their unofficial honeymoon in Germany; this immersion in Spinoza’s philosophy of interdependence and interconnectedness would deeply inform her fiction. Back home in London, Lewes urged her to write a story—they needed the money to support his wife and sons—and George Eliot was born.

¤

So, for both Kierkegaard and Eliot, remarkably fertile years as artist-philosophers followed a momentous, life-defining personal choice. Their leaps set them at odds with the world, put them under intense emotional pressure, made them feel they had to justify themselves. Was their work the telos of these leaps—some deep, perhaps inchoate vocation or ambition striving to realize itself, and finding its thorny path? Or did these traumatic decisions bring a new sense of self, and a newly troubled relationship to the world, that prepared the ground for extraordinary creative work? Was this preparation a process of self-understanding, self-realization—or was it a sheer shock, which provoked a philosophical response? Did they gain an experience of freedom that empowered them with a heightened sense of their own agency? Or did choosing cause profound anxiety? All these possibilities may not be mutually exclusive: not necessarily an either/or.

Analyzing the letters Eliot wrote from Germany in 1854, her very astute biographer Rosemarie Bodenheimer observed how she portrayed herself as a “heroic chooser.” Eliot’s tone was haughty and defensive. “I do not wish to take the ground of ignoring what is unconventional in my position,” she wrote to one of her closest friends.

I have counted the cost of the step that I have taken and am prepared to bear, without irritation or bitterness, renunciation by all my friends. I am not mistaken in the person to whom I have attached myself. He is worthy of the sacrifice I have incurred, and my only anxiety is that he should be rightly judged.

Here Eliot, conscious of being cast as a fallen woman, assumes a high moral stance. Bodenheimer reconstructs her train of thought as follows:

She has “sacrificed” her other relationships for a higher calling—surely a womanly thing to do? And she has chosen, not fallen, for she has “counted the costs,” assessed the consequences, prepared herself to bear them, and made her move. The heroic chooser is, moreover, better than her friends because she will not judge them for judging her.

Construing choice as sacrifice rather than selfishness, weighing consequences, elevating the unconventional chooser above those who might judge her choices harshly—these would soon become themes in Eliot’s novels. Yet what is truly interesting here, Bodenheimer adds, is Eliot’s “knowledge of how these positions fail.”

In other words, when a woman leaps, she is in danger of falling. The Mill on the Floss (1860), George Eliot’s second and most autobiographical novel—written six years after she leapt into life with Lewes—is profoundly ambivalent towards such leaps. Eliot’s heroine, Maggie Tulliver, is cursed by a marriage question that demands a hard “labour of choice.” Maggie’s judgmental neighbors perceive her as a fallen woman. Again, in the later novel Romola (1863), Eliot’s heroine struggles under a “burden of choice”—and does her best to avoid this burden altogether.

Eliot’s own marriage plot took a new twist after Lewes died at the end of 1878. She was now close to 60, overcome by grief and contemplating her own death. Yet within a year she was facing a new romantic dilemma, and another dramatic leap. Two besotted younger suitors vied for her affections: a talented writer and activist named Edith Simcox, and John Cross, a wealthy banker whom Eliot and Lewes used to call their “Nephew.” In the spring of 1880, she married Cross, who was 20 years her junior. “Choice of Hercules,” Eliot wrote in her diary. As in 1854, nasty gossip flew around London’s drawing rooms. “He may forget the twenty years difference between them, but she never can,” hissed one younger, prettier woman after she met the newlyweds. “[S]uch a marriage is against nature.”

Eliot sent her closest friends news of her marriage to Cross only after the fact, and from a long distance. In these letters, written from the couple’s honeymoon in Italy, she effaced her own choice in the matter. “A great momentous change is taking place in my life—a sort of miracle in which I could never have believed, and under which I still sit amazed,” she wrote to one friend, spinning the story as a romantic fable and casting herself as a bewildered Cinderella. “All this is wonderful blessing falling to me beyond my share, after I had thought that my life was ended,” Eliot wrote to another friend, as if her marriage had dropped out of the sky. Her fairy tale soon took a nightmarish turn. While still on their honeymoon, Cross suffered a mental breakdown and leapt out of the window of their Venice hotel. He was fished out of the Grand Canal unharmed, but the gossips back home whispered that George Eliot’s new husband had tried to drown himself—he would rather jump out of a window than into bed with his aged wife. The couple soldiered on through a few months of marriage before Eliot died, quite unexpectedly, at the end of that same year. We can only imagine how their shared life unfolded after Cross’s leap.

This melancholy last chapter in Eliot’s biography complicates our image of the heroic chooser who reshaped the meaning of modern marriage with her scandalous example. We may feel disappointed that, when this brave, brilliant woman was finally legally married, she represented it as being chosen rather than as choosing. Of course, women have long been taught to think this way about marriage. And Eliot had special reasons for clinging to the demure ideal, despite her formidable intelligence and her fierce ambition. Almost everyone had shunned her when she settled down with Lewes. That traumatic choice severed her from friends and family. She did not want to fall again. Perhaps it is no wonder that Eliot shrank from choosing again—or at least from being seen to choose.

¤

Kierkegaard’s marriage question, like Eliot’s, was never comfortably resolved. After he died and his will was opened, Regine learned that he had bequeathed everything to her. He knew that his whole life had been marked by his refusal of marriage and intimacy. That refusal casts a shadow, retrospectively, onto his childhood: what were the early experiences that made him unable to marry? Kierkegaard once wrote that marriage requires complete openness between husband and wife, and that he could not open himself to another person in this way. Perhaps he was driven by his artistic and philosophical vocation to seek a solitary life. Or perhaps his decision to stay single (and celibate, as far as we know) was shaped by the belief, held as sacred by his Christian church, that certain forms of desire—homosexuality, for example—were sinful and shameful. Kierkegaard took these questions to the grave, boasting that no one would ever discover the secret that explained his inner life. All we know is that he felt unable to become a husband, and that he interpreted this incapacity as a spiritual situation.

He returned again and again to the marriage question in his writing, trying out new narratives to make sense of his broken engagement—or perhaps heaping fresh layers of obfuscation and diversion upon his guiltily guarded secret. In 1850, nearly 10 years after he broke up with Regine (by now she was happily married to someone else), he waded into a political debate about Martin Luther’s marriage, declaring that its meaning lay in scandal and defiance, not bourgeois respectability. Kierkegaard generally disdained politics, but this particular issue touched a nerve. Religious freedom had just been enshrined in Denmark’s new constitution, and the Lutheran state church was renamed the Danish People’s Church. These developments raised fresh questions about marriage. Several influential Danes called for the introduction of civil marriage, citing Luther’s own example in support of their cause—after all, Luther, a monk, had married a nun, breaking all his church’s rules on both marriage and monasticism. Denmark’s chief bishop insisted that Luther’s marriage was a Christian union, not merely a civil contract. Kierkegaard disagreed with both sides in this debate. Luther’s marriage was significant not because it belonged inside or outside any church, he argued, but because it echoed the “divine scandal” of Jesus’s own life and death. Luther could just as well have married a kitchen maid or a door post—for his sole aim was “defy[ing] the whole world.” It was no coincidence that this interpretation put Kierkegaard’s own marriage drama on par with Luther’s: deciding not to marry Regine after becoming publicly engaged to her was as subversive as Luther’s decision to marry a nun had been in its day.

Eliot’s marriage question also put her at odds with official Christianity—in her case, the Anglican church. Again, this had lifelong consequences. While Charles Dickens, known to be a cruel and unfaithful husband, was buried in the hallowed Poets’ Corner of Westminster Abbey after he died in 1870, the Church of England’s leaders decided that the author of Middlemarch (1871–72) did not belong there. When John Cross tried to persuade them to honor his wife among her country’s great writers, these pious men cited her “notorious antagonism to Christian practice in regard to marriage” as their reason for keeping her out.

For 24 years, Eliot had referred to Lewes as “my husband”; he referred to her as “my wife” and as “Mrs Lewes.” “It is a great experience—this marriage!” she once confided to a friend. “I can’t tell you how happy I am in this double life which helps me to feel and think with double strength.” By recasting marriage as an “experience” rather than a legal status or a social convention, she was wresting the very concept of marriage from the grip of both church and state.

Eliot’s defiantly idealistic portrayal of the “perfect love” and “perfect happiness” she shared with Lewes must be complicated by the great risks, high stakes, and deep pitfalls of marriage, which are analyzed unflinchingly in her novels. Readers are left in no doubt that marrying the wrong person can be spiritually devastating. The heroine of one of Eliot’s first stories, “Janet’s Repentance” (1857), is a wife driven to alcoholism by her husband’s violence and by her own grief at the desecration of their love. Janet’s bitter marital disappointment recurs in Eliot’s later novels. It is the fate of the eponymous heroine of Romola, of both Dorothea Brooke and Dr. Lydgate in Middlemarch, and of Gwendolen Harleth in Daniel Deronda (1876). Gwendolen, Eliot’s most compelling heroine, is worse than disappointed; she is morally and sexually violated by her abusive, coercive husband. While Janet resorts to alcoholism, Gwendolen develops symptoms of hysteria and anorexia, illnesses just gaining medical attention in the 1870s when Eliot wrote this final novel.

Partly because of its emotional difficulty and moral complexity, Eliot portrays marriage as a site for personal growth. This is above all the theme of Middlemarch. Early in the novel, 18-year-old Dorothea hopes to fulfill her intellectual ambitions by marrying Edward Casaubon, an amateur scholar twice her age. “Dorothea, with all her eagerness to know the truths of life, retained very childlike ideas about marriage,” comments the narrator dryly. Imagining that it must be a “glorious piety” to endure the odd habits of a great man, Dorothea looks dreamily at Casaubon and sees “a modern Augustine.” She is in awe of his deep feelings and vast experience—“what a lake compared with my little pool!” She tells herself that she will “learn everything” if she becomes his wife.

The Casaubons’ honeymoon turns out to be a rude awakening for both partners. Dorothea soon realizes that her new husband’s soul is not the great lake she had imagined it to be. “[I]n courtship,” Eliot explains,

everything is regarded as provisional and preliminary, and the smallest sample of virtue or accomplishment is taken to guarantee delightful stores which the broad leisure of marriage will reveal. But […] [h]aving once embarked on your marital voyage, it is impossible not to be aware that you make no way and that the sea is not within sight—that, in fact, you are exploring an enclosed basin.

Dorothea’s situation is doubly ironic. She has been most foolish in her search for wisdom, most mistaken in her pursuit of knowledge. Yet she does in fact learn a lot from this relationship, precisely because it was such a huge mistake. Her childish naivete had been mixed with arrogance, and as Mrs. Casaubon she is both enlightened and humbled. Her hard-earned emotional intelligence transforms her past mistakes into wisdom. Late in the novel, in a moment of crisis, Dorothea finds that all her “vivid sympathetic experience returned to her now as a power.” It illuminates the path ahead, “as acquired knowledge asserts itself, and will not let us see as we saw in the day of our ignorance.”

Kierkegaard also drew spiritual lessons from his romantic suffering. “[M]y life is a daily martyrdom,” he wrote in 1849, brooding on his break with Regine. Fixated on the idea of imitating Christ, he saw his own experience mirrored in Jesus’s public humiliation at the crucifixion—a spectacular suffering, held aloft for all to see. “It is really a blessing and a comfort to me right now to know before God that I suffered in leaving her, that it was sheer suffering,” he wrote on another page of his journal. “What strength it gives me!” Though he had long since mastered Plato’s metaphysics and Hegel’s logic, Kierkegaard was still entangled in his marriage question. His own misery had been “greatly intensified by having made her unhappy,” yet at the same time, he explained, “a wealth [of creativity] burst from my soul which appalls me when I look back upon it.” He meant Either/Or, and the sequence of brilliant books that followed it. This Kierkegaardian marriage plot was a story of suffering, sacrifice, and triumphant resurrection.

Eliot, by contrast, moved decisively beyond Christianity in her final novel, Daniel Deronda. Its moral and spiritual currents flow through virtuous Jewish characters, while the Anglican establishment fails to protect or nurture human goodness. The novel ends with two alternative visions of a meaningful human life. Deronda, an English aristocrat who has discovered that his mother was Jewish, embraces his heritage by marrying a Jewish woman and sailing to “the East” to found a nation for his people. Quite how he is going to accomplish this grand task is never explained. Gwendolen, once a petulant, selfish “spoiled child,” gains a “new divination” from her humiliating experience as a wife. Now a young widow, she has a second chance. “I mean to be very wise; I do really,” she tells her long-suffering mother. “And good—oh so good to you, dear, old, sweet mamma, you won’t know me.”

Gwendolen is determined to “be better.” “I do not yet see how that can be,” she admits. But she is filled with new determination, new humility, and new hope. She has searched within herself and found a capacity to choose goodness—a choice she was unable to make before—though she remains uncertain what shape this will take in her life. Her uncertainty makes the choice all the more powerful. It is a Kierkegaardian leap. And here the novel ends. To the frustration of generations of readers, Eliot refuses to tell us what happens to Gwendolen after her leap.

¤

LARB Contributor

Clare Carlisle is the author of Philosopher of the Heart: The Restless Life of Søren Kierkegaard (FSG, 2020) and The Marriage Question: George Eliot’s Double Life (FSG, 2023).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Hail Wedded Love

Andrew Cutrofello reviews Paul A. Kottman's "Love As Human Freedom."

Love Is Never a Given

Skye C. Cleary talks to Andrea Miller about her new book, "Radical Acceptance: The Secret to Happy, Lasting Love."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!