TO SUSTAIN A FIRE, you need not only fuel and kindling but also some dutiful custodian to routinely prod and fiddle with the pieces. Extinguishing it requires no less added effort. The useless smoldering of an unattended flame, impotent as it is for cooking a meal or warming a party, must nonetheless be deliberately doused and cleared when we are done with it. Otherwise the embers, subject to the slow prodding and fiddling of the elements themselves, may very well spring back to life long after the party’s gone away. And that’s how whole blocks burn down suddenly in the nighttime.

Smoldering is the natural state of fire pits. But as any Boy Scout knows, it only takes a little conscious effort to coax them toward our preferred extremity; a little neglect to let them go the other way.

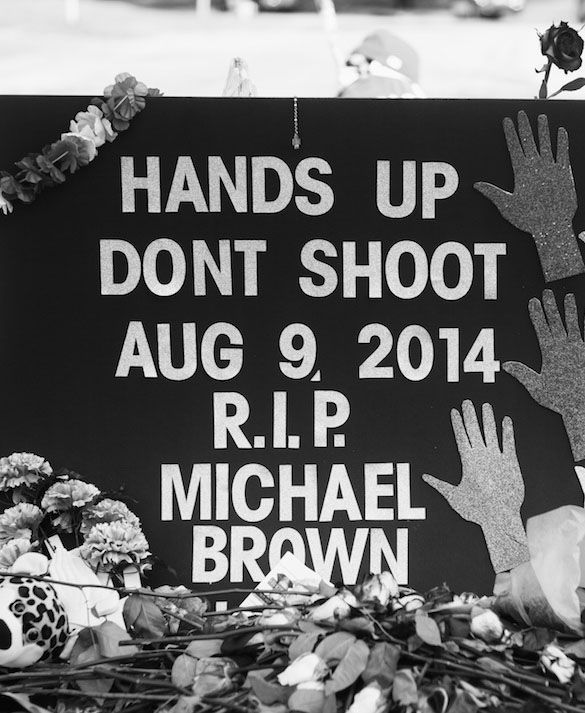

On August 25th I drove to Ferguson with a young activist from Chicago (“After the Train Leaves Town: A Report from Ferguson”). It had been 16 days since Darren Wilson shot Michael Brown, the day of his funeral, and the first day since without major protests. The timing was deliberate. I was curious to know what shape the soot would take after the flame began to die down. Months later I still find myself in conversations with acquaintances who ask what it was like. Being that it is generally considered poor form at a party to call up a long essay on a small screen and hand it over for reading, I’ve tried to boil what I remember down to a party-length reply. “It was very hot,” I usually say. “It was a lot of folks trying very hard to act normal.”

“So its calmed down?” is the typical follow-up. “Everyone is tired,” I say.

At this point, if the conversation persists, if we have moved past casual curiosity into a more involved discussion, I do take out my phone to find and read something Tommy Pierson, Ferguson’s representative in the Missouri Legislature, told me a few hours past the funeral — a canceled march providing him his first free afternoon in weeks:

“I’ll tell you, I’m tired. I’m sleep deprived. I’m glad they canceled the march,” he says, “Now everyone is waiting to see what happens with the officer […] If they don’t indict, and the Feds don’t step in, I think you’re gonna see the streets fill up again.”

As it happens they didn’t indict and now the streets are filling up.

The events that will follow, the events that have, even within minutes of the announcement, already happened, are predictable in outline. Protestors will march. Cameras will descend. Most of it will be peaceful, but some violent and this is what the cameras will focus on. Windows will be broken and cars will be set on fire, in this case at the very moment President Obama came on television to caution against those very acts. Police will respond and they will not respond as well as they might. Other cities will see smaller incidents. Organizations with a dog in the fight will step in; organizations without a dog but hoping to ride one to some better exposure will follow suit. The fire will burn and then after a while everyone will get tired again. We know these things will happen because their happening is as much by necessity as they are by agency — they’re how the script goes, and by that I do not mean they are bad or boring things, only things that happen in part because we feel they must, because we have been through this so many times before.

We know the arguments we’ll hear as well. Raw protests at the injustice. Context providers to explain just how unusual the proceedings of this Grand Jury were. Calls to action. Recapitulations of the whole racial history of the United States with heads shaking and I knew this would happen because this problem is systemic. Celebrations by Wilson sympathizers; excessive focus on the criminality of half a dozen protesters; the high-horsers who, like in the aftermath of Zimmerman, appeal to the procedural correctness on the evidence, relying, somewhat inexplicably, on the credulity of the notion that these appeals to idealism carry water in a country where such dispassionate objectivity does not apply to black defendants. Expressions of anger and frustration and fear and commitment and bravery.

They will largely be worthy points, and to varying degrees good ones. Like the events above, the essays that will express these ideas are matters of instantiation rather than invention — the inevitable formalization of insights already widespread. Some will be profound and shared in solidarity; others will be stupid or insulting and they too will be shared, this time in condemnation. Some will only be comforting and these, perhaps, will be the most important things to share. It is good and right that this will happen, I think, but for my part I am having trouble mustering the fortitude to search for sermons in the suicide.

Mainly I would like to be in bed. Mainly I am stopped by considering that I have the luxury to do that if I want, that I do not live under the threat that killed Mike Brown. Mainly this reminds me that the personal is still political, and more importantly, that the political is inescapably personal for the unlucky and oppressed.

¤

The protestors last night and the protestors today do not suffer from the same deficits of energy. They are all energized and driven and sublimating sadness and anger into purpose now, not just in Ferguson but everywhere I look from the people who shut down Chicago’s Lake Shore Drive last night to activists on every social media platform I can find. Yesterday’s announcement was the prod that turned the flame back on, and that fuel will keep them going for a while. The jolt was fast. Even hours before the decision, The New York Times reported that despite crowds gathering, “some protestors who participated in past demonstrations said they were unlikely to join them again because of the cold weather or because they could not afford to miss work.” Ordinary life was still in charge. Months later, everyone was still tired. Now the switch is flipped and inertia working the other way. The kindling is prodded; fresh fuel is added. The fire burns long enough to make a point, to avoid being doused entirely. Then it will die down again.

This is all brave and it is all worthy but I am having trouble believing that anything will happen. This is not to say that protests should not happen — there is virtue in the mere registration of discontent. But the result is ground held, not taken. Although it would have been the same with an indictment: preferable, certainly, but no more effectual in the larger scheme.

The reason is obvious I suppose, but like all of these reflections it must nonetheless be articulated. Darren Wilson shooting Michael Brown is a symptom of our racial calamity. It is not even a whole symptom in itself, it is one small spot in a secondary rash, a rash composed of black bodies, murdered by police and civilians and electric chairs in circumstances never sufficient to do the same to white folks. To treat such a symptom is just and good, but it is only management, not cure. To believe otherwise is to believe that had a jury found George Zimmerman guilty, Michael Brown would be coming home for Thanksgiving break right now. It is to believe that because a jury found Michael Dunn, who opened fire into a car of unarmed black teens, guilty of murder, they won’t need to do the same for another Dunn next year.

(I do not mean, in all of this, to say that there is no value whatsoever to indictments. Symbols, even in their symbolism, are significant. And for some particular players they are not symbols at all. For Lesley McSpadden, Michael Brown is not synecdoche. He is her son and he is dead and now she will never see the perpetrator punished. But here I am speaking only of the general issue, of America and the consequences of its original sin).

The truth is that, in the general sense, the failure to indict is not a lost battle because the stakes of an indictment of a single man are too small for such dramatic placement. And so it is worse than a lost battle: it is an insult. It is a denial of even small consolation and this is why the frustration is so raw. A battle can be lost with honor. An insult can only be taken with a turned cheek or responded to in anger.

It would be easier if it were the other way. If the indictments and prosecutions were where the war was won and lost, not just survived. This is the world in which Michael Dunn is a liar, where his thought was I’m going to kill these black kids and I’m going to get away with it too — one where Darren Wilson thought the same thing. Then catching and punishing him and others like him would be the whole game. But as it is we live in a world where I believe him when he says that the sight of loud dark bodies on a dark night in a car made him fearful for his life and this is the real problem, one that playing whack-a-mole with incidents can’t solve, even if every murderer was found guilty. I believe Darren Wilson when he says he felt like Michael Brown was “like a demon,” and that he felt like “a five year old holding onto Hulk Hogan.” I believe George Zimmerman thinks that Trayvon Martin, and people like him, are “assholes” who “always get away.” It is a problem that symbolic victories do not have the capacity to mend.

Let me go further. The fire is stoked from time to time. The “conversation” — the redemption activists seek to “keep going” every time this happens — is ignited for a while. This is a good thing, but we do not actually know if it will ever warm the room. Advocates can never keep it going long enough because they are preoccupied just beating off self-satisfied DAs stepping up to microphones and bearing water pails. That they persist is vital, but the notion that perseverance will finally grant access to the core of our national character is an article of faith. Perhaps it would. But we are troubled by a buried yet ineradicable suspicion that the trauma is beyond what even the most robust conversation can resolve. \

We are getting ahead of ourselves. The pain of yesterday is not the pain of a chance for resolution missed. We’ve never gotten so far. Yesterday was the pain of again being served a missed chance of even having a chance of finding out if resolution is possible at all.

There are declarations about keeping the conversation going, but perhaps the first task is getting the language in which that conversation will be carried out agreed to in the first place. Yet difficulties of translation stem from the same cause as Dunn’s genuine fear; the possibility of beginning is perhaps tied up in the success of the conclusion. And so the question begs itself, and the headache comes back and the fear sets in.

¤

It will go on, in days, in weeks, in months and years. With an indictment, activists would have moved next to the trial. Without one, they will stay with protests for a while, then smolder, then reignite with the next body left rotting on the asphalt in the sun. It is altogether fitting and proper that they should do this. They will prevent anyone from pouring water on the embers, at least. All of this has made me cynical, but not so cynical that I no longer believe in the possibility of survival. That much will continue, and that much is — in the sense that life persists at all times and plays out against these backdrops — something just short of victory in itself.

I have belabored the metaphor of a campfire because it fits: the uneasy suspension, the oscillations between the possibilities of activity and silence, the passing of most days in a murmur of greying ash and little smoke and orange glow. The countervailing forces of antagonistic agencies (and acts of God on top of those) in determining what happens next. But it is fitting in another way. The proverbial fire is the conversation about race but it is also the faith that that conversation will be some part of our redemption. Murmuring, usually, sometimes stoked — fire is a common metaphor for this even in platitudes: the people on the street are burning with a desire for justice. We are all, at our best, consumed by the desire to believe in the real possibility of a transformative moment, and we are most consumed it seems on the nights when that belief appears most tenuous. Fire can be difficult to predict that way.

I should except myself from that last “we.” I am mainly tired and frustrated and scared. I am doubtful and I want to go to bed. But in the course of these last hours, I have begun, I think, to reassure myself that belief in the possibility of transformation is the only alternative to nihilism. That shouting in the wilderness is still perhaps preferable to being silent even if it cannot help because the shouting itself is a function of life. The activists know this. I am still smoldering. But fire spreads quickly.

¤

Emmett Rensin is an author, essayist, and playwright, originally from Los Angeles, CA.

LARB Contributor

Emmett Rensin is an essayist and contributing editor for the Los Angeles Review of Books. His work has appeared in The Atlantic, The New Republic, the Los Angeles Times, and elsewhere. He currently lives in Iowa City.

LARB Staff Recommendations

There Are Some Things I Just Can’t Tell You About

After the Train Leaves Town: A Report from Ferguson

What happens to a town racked by racial violence when the media and the public move on?

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!