Acknowledgment Is Not Enough: Coming to Terms With Lovecraft’s Horrors

Can we still enjoy Lovecraft? Alison Sperling on "The Age of Lovecraft."

By Alison SperlingMarch 4, 2017

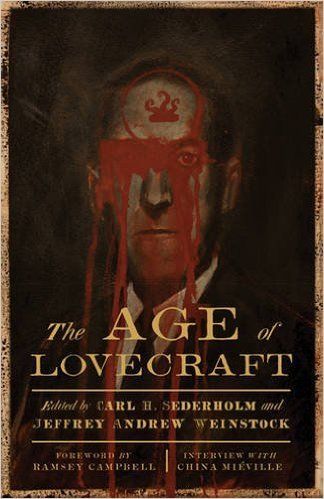

The Age of Lovecraft by Carl H. Sederholm and Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock. University of Minnesota Press. 296 pages.

AS A FEMINIST, I am reluctant, at times, to admit to friends and academic colleagues that I appreciate H. P. Lovecraft’s work. His racism and dismissive, discriminatory attitudes toward women do not just haunt his tales; they are central to his mythos. Critical scholarship on the author has only recently started to grapple with the tension between the philosophical implications of his work and its inherent xenophobia. Lovecraft may enjoy a current vogue among predominantly masculinist philosophical methodologies, but he remains unpopular for those unwilling or unable to delve beyond his racist and misogynistic attitudes.

Edited by Carl H. Sederholm and Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock, The Age of Lovecraft is a collection of 11 essays and one interview that questions Lovecraft’s recent reemergence as a cultural force. The collection argues for Lovecraft’s place in modernism, and more provocatively demonstrates the many ways in which the contemporary moment belongs to Lovecraft. As James Kneale suggests in his contribution to the book, the age of Lovecraft is “an age in which we are clearly still living.” Kneale’s claim is not just that we now live in an age for which Lovecraft might be a figurehead, but that it’s been that way for some time.

Lovecraft is one of those authors that most people have heard of, but few seem to have read. That’s because his influence is everywhere. From contemporary comic book appearances and popular role-playing games to Swiss surrealist paintings and American heavy metal music, the legacy of Lovecraft’s mythos has been revived, and since his quiet death in 1937, his legacy — once impoverished and unrecognized — has flourished. So when exactly is (or was) the age of Lovecraft? And if it’s now, then why?

Elevated from pulp author to canonical classic when the Library of America published his oeuvre in 2005, Lovecraft has since been revived in both literary criticism and philosophy. In the last decade or so, Lovecraft’s tales, letters, and essays have reemerged with intensity, markedly in the influential philosopher Graham Harman’s book Weird Realism: Lovecraft and Philosophy (2012). Lovecraft’s work has repeatedly appeared in philosophical essays and books that follow in Harman’s speculative realist tradition, where the tales often serve as literary examples par excellence. Harman’s presence in The Age of Lovecraft looms across the diverse essays, reaffirming his command of Lovecraft studies despite the grievances that many authors air regarding his approach to the burgeoning field.

The reemergence of Lovecraft’s work within this context is therefore no coincidence. The adoption of Lovecraft by speculative realists marks his work as a quintessential example of literature that denies the centrality of human life within a rapidly expanding cosmos, where humans feel their smallness and insignificance in the face of larger and more powerful cosmic forces. His fiction serves as a link between the modernist period and the contemporary one through this de-emphasis of the human and the inherent inability to fully comprehend the mysteries of the universe. In the Anthropocene — a term generally accepted across disciplines to mark our current geological epoch — it is perhaps clear why a writer with what S. T. Joshi has called Lovecraft’s “cosmic pessimism” would serve as a contemporary philosophical model.

In their introduction to the volume, Sederholm and Weinstock write that it is “against all odds” that Lovecraft has become “a 21st century star.” The introduction thoroughly accounts for Lovecraft’s widespread influence throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, and it charts references to his mythos across global literary and popular cultures. But indeed, the odds were against his apparent prevailing influence — he died impoverished, selling stories to pulp magazines just to feed himself, and he enjoyed no real popularity or fame during his lifetime. In the 21st century, as the editors explain, there are other elements working against his reemergence as a celebrated literary figure, including Lovecraft’s well-documented racism and xenophobia, which can be found in his letters and stories. Sederholm and Weinstock believe that Lovecraft’s racism cannot be separated from his fiction, that it must be taken a central tenet of his writing and his philosophy.

Though the essays span a wide variety of subjects related to Lovecraft’s work and influence, some essays may be loosely grouped together for their shared theoretical foundation in speculative realism and/or new materialism. The book begins with James Kneale’s “‘Ghoulish Dialogues’: H. P. Lovecraft’s Weird Geographies,” which begins from Harman’s influence on the study of Lovecraft’s style and form, but ultimately argues for a marriage between the examination of form and content in his work. Kneale emphasizes the presence of technologies throughout Lovecraft’s tales (telescopes, telephones, radios) that together reveal the presence what he calls a “weird geography” — a distance or gap between space and time that troubled Lovecraft, and that also serves to merge form and content in his tales.

Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock’s “Lovecraft’s Things: Sinister Souvenirs from Other Worlds” cites speculative realist and object-oriented philosophers from Harman to Ian Bogost, but draws primarily from Jane Bennett’s work on enchantment in order to interrogate what readers find appealing and satisfying in weird and gothic fiction. His attention to the “things” in Lovecraft (and in other Gothic narratives) places Lovecraft’s work in a tradition he calls “dark enchantment” that is characterized by a postmodern cynicism aroused by “thing-power,” a portal that is opened up to the other and to the outside.

Perhaps the most original of this group is the contribution from Isabella van Elferen titled “Hyper-Cacophony: Lovecraft, Speculative Realism, and Sonic Materialism.” Van Elferen looks at Lovecraft’s work through the lens of critical musicology in order to point out the inconsistencies in Lovecraft’s thinking and to challenge his prevailing place in speculative realist philosophy. What she provocatively calls “alien timbres” — the sonic qualities of Lovecraft’s literary scenes and creatures — alludes to profound conditions of immateriality and is thus incommensurable in many ways with speculative realism. Her essay urges us to consider Lovecraft’s greater universe, and it draws our attention away from the dominance of visual references in order to think about Lovecraft’s hyper-cacophony.

Three essays in the collection offer feminist and queer readings of Lovecraft’s writing and ethics. Carl H. Sederholm’s “H. P. Lovecraft’s Reluctant Sexuality: Abjection and the Monstrous Feminine in ‘The Dunwich Horror’” argues that despite critics’ outstanding claims that sex has no place in Lovecraft, the author’s sexual loathing, fear of women, and horror at the means of human reproduction is expressed throughout his stories and correspondence and is central to his figuring of the human body.

Lovecraft’s fear of otherness is also explored in Jed Mayer’s “Race, Species, and Others: H. P. Lovecraft and the Animal,” one of the best essays in the collection, which examines the influences of evolutionary narratives that have elevated certain species over others, and grapples with the racist attitudes inherent in Lovecraft’s own speciesism. Drawing from contemporary animal studies scholarship, Mayer explores the inherent conflict between Lovecraft’s own fear of kinship with other ethnic groups and his obsession with imagining connections (genealogies, intimacies, histories) with nonhuman beings. Mayer broadens his inquiry by asking how questions of racism and speciesism inform the genre of weird fiction more broadly. He argues that without forgiving Lovecraft’s racism, we can recognize the provocative notion in Lovecraft’s work that “however much we learn about the other, it remains alien.” Mayer demonstrates that Lovecraft’s racism “is what paradoxically becomes the means by which his stories achieve intimate contact with the feared other.”

Patricia MacCormack’s contribution, “Lovecraft’s Cosmic Ethics,” is perhaps one of the boldest essays of the collection; it serves as a powerful climax to the volume as a whole. Here, MacCormack, who has been one of the few women writing in Lovecraft studies, argues against critics who dismiss Lovecraft for racism, proclaiming instead that he offers a way into “feminist, ecosophical, queer, and mystical (albeit atheist) configurations of difference.” Acknowledging that her reading may seem “perverse” (and it is, in more ways than one), MacCormack says that “this writer of unimaginable horror […] can also be argued to offer a glimpse into unimaginable structures forged through connectivities.” In a vein similar to Mayer’s essay, MacCormack writes that Lovecraft’s “total inclusion” of the complete foreignness of the universe forces a reorienting of traditional criticisms of his work as simply racist and xenophobic. In the last pages of her essay, she shifts her discussion to sex, persuasively arguing that Lovecraft’s work is more focused on desire than sex, perhaps even offering a queer refusal of satisfaction or completion; his works are characterized by moods of profound suspension within a perpetual state both “within and beyond a frenzy of potential.”

Other essays in the collection offer useful examinations of the influence of Lovecraft’s work on other texts and genres. In “Prehistories of Posthumanism: Cosmic Indifferentism, Alien Genesis, and Ecology from H. P. Lovecraft to Ridley Scott,” Brian Johnson reads Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) alongside Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness (1936), interrogating how Lovecraft’s cosmic indifferentism strongly influences Scott’s prequel Prometheus (2012). Johnson effectively reveals a shift in the way Ridley Scott’s thematic preoccupation with human origins can be understood as he moves away from the monstrous feminine of Alien toward a

planetary version of the Frankenstein myth in which the beneficent mother is always already absent, her generative power usurped in advance by the “new Promethianism” of paternal science that appropriates creation as its exclusive province.

Moving from the screen to the graphic novel, David Simmons’s “H. P. Lovecraft and Real Person Fiction: The Pulp Author as Subcultural Avatar” considers real person fiction in graphic novels as a way to challenge and upend Lovecraft’s changing cultural position. He makes the argument that we must see Lovecraft as a fictional persona and not a static biographical figure. His essay can be usefully read alongside Jessica George’s “A Polychrome Study: Neil Gaiman’s ‘A Study in Emerald’ and Lovecraft’s Literary Afterlives,” which reads Lovecraft as a destabilizing figure; George sees this as perhaps one reason why he is so prone to reworkings and reimaginings, particularly in Gaiman’s work. These contributions reopen what many would consider closed discussions regarding authorship and biography as they challenge readers to think of Lovecraft and his influence beyond the pages of his tales.

The Age of Lovecraft is a welcome addition to the growing body of scholarship focused on Lovecraft, and it contains several essays that are especially important within this field. These essays have certainly helped me think about my own relation to studying — and even enjoying — Lovecraft’s work, given that I am someone invested in non-oppressive, queer, and feminist critiques of literature and culture. The contributions that answered the call of the editors’ introduction and their collective refusal to separate Lovecraft from the problem of racial difference were particularly effective in this regard. Their sentiment is underscored in a wonderful interview with China Miéville at the book’s conclusion: “Acknowledgement [of racism, misogyny, xenophobia] is absolutely not enough,” Miéville says. To properly and ethically read Lovecraft in the 21st century, to celebrate his view of the cosmos and to herald his philosophy as ahead of its time, or to claim that we may live in an “Age of Lovecraft” in the present day, one must also accept the difficult responsibilities associated with taking on his discriminatory attitudes as keys to informing his philosophy. What does it mean that out of prejudice, fear, and a hatred of otherness was born a literary tradition that has particular merit in the contemporary moment? This collection helps readers of Lovecraft work through the incorporation of his deeply problematic attitudes into the ways we think about his work and its place in literary criticism and theory. It advances efforts to do more than just acknowledge Lovecraft’s problematic politics by actually showing the ways they are entangled with form, content, ethics, and his vast fictional universe.

¤

LARB Contributor

Alison Sperling is an IPODI Postdoctoral Fellow at the Technical University Berlin and an Affiliate Research Fellow at the Institute for Cultural Inquiry Berlin. She researches the Weird and science fictional in literature and visual culture, feminist and queer theory, and the Anthropocene. She has published in Rhizomes, Girlhood Studies, and Paradoxa, with forthcoming work in Science Fiction Studies and The Routledge Companion to Science Fiction. She is also the editor of a recent issue of Paradoxa: Studies in World Literary Genres on “Climate Fictions.” She is currently at work on her first book project, Weird Modernisms.

LARB Staff Recommendations

“Foul, Small-Minded Deities”: On Giorgio De Maria’s “The Twenty Days of Turin”

Peter Berard explores the haunting implications of “The Twenty Days of Turin” by Giorgio De Maria.

A Conversation Between Timothy Morton and Jeff VanderMeer

Novelist Jeff VanderMeer and philosopher Timothy Morton explore literature, climate change, hyperobjects, surrealism, coffee, and shedding cats.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!