A Serious, Chronic, Complex, and Systemic Disease: On Jennifer Lunden’s “American Breakdown”

Tanya Ward Goodman reviews Jennifer Lunden’s “American Breakdown: Our Ailing Nation, My Body’s Revolt, and the Nineteenth-Century Woman Who Brought Me Back to Life.”

By Tanya Ward GoodmanMay 31, 2023

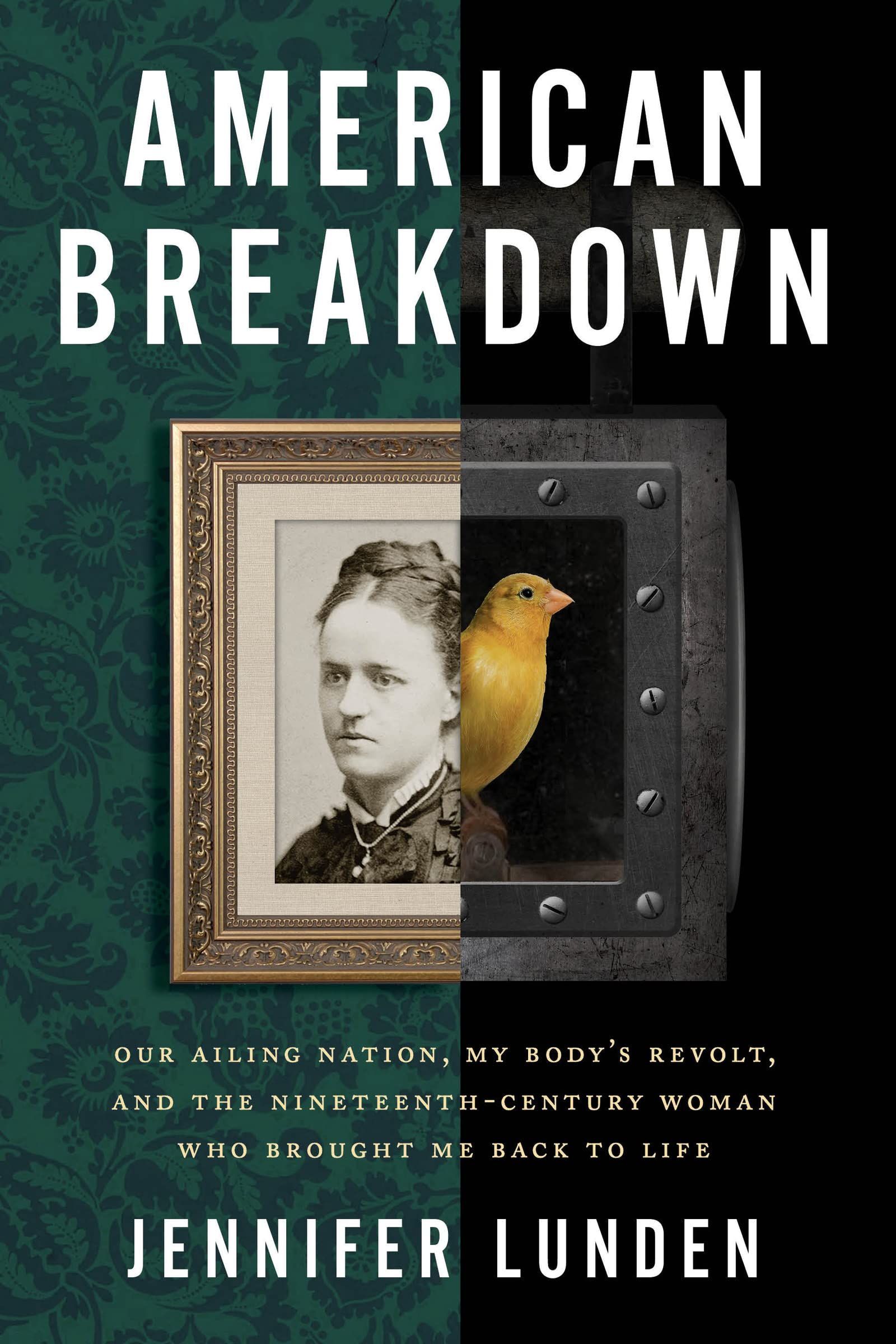

American Breakdown: Our Ailing Nation, My Body’s Revolt, and the Nineteenth-Century Woman Who Brought Me Back to Life by Jennifer Lunden. Harper Wave. 464 pages.

A FEW MONTHS into the pandemic lockdown, I noticed the silver dollar eucalyptus in our backyard was looking a little wan. Its leaves were sparse and brittle, and when I put my ear to the trunk, it sounded as if a bowl of Rice Krispies had just been drenched with milk. Over the phone, my arborist explained that my tree was dying. Beneath the bark, the tree’s complex system of xylem was drying out and shutting down. In other words, my tree was having a slow heart attack and had been suffering silently for some time.

The fate of my eucalyptus and the way its demise fit into the larger story of local drought, climate change, and the global pandemic was top of mind as I read Jennifer Lunden’s new book American Breakdown: Our Ailing Nation, My Body’s Revolt, and the Nineteenth-Century Woman Who Brought Me Back to Life. Using the medical memoir as an entry point, the author has woven a complex story of industrialization, environmental degradation, capitalism, and the crumbling state of healthcare in the United States. With no single place to lay blame for her own illness, she seems to find some relief in the active search for connection. “We’ve become masters at breaking things down to their smallest components so we can study them,” she writes, “but our fragmented, mechanistic way of viewing the world comes at a cost.”

The author’s account of this cost begins in 1989 when, at the age of 21, she moved from Canada to Portland, Maine. She positions us in time and hints at the book’s overarching themes with references to the inauguration of George H. W. Bush, the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Prince William Sound, and the advent of Prozac, while also writing optimistically of building her own life “from the ground up.” The loving description of her first apartment, where she “hung the crystals from the windowsills and pinned the Georgia O’Keeffe print over my bed,” turns elegiac when Lunden’s sudden illness transforms this bed from refuge to prison.

Five years later, in 1994, with lingering and mysterious fatigue her constant companion, Lunden found company, focus, and hope in Jean Strouse’s biography of 19th-century diarist Alice James. Describing her own youth as “crushed and bewildered before the perpetual postponement of its hopes,” James (the sister of author Henry James) suffered headaches, brain fog, and exhaustion. This mass of symptoms was defined in 1869 by neurologist George Beard as “neurasthenia.” “I didn’t know then that the book was treasure in my hands,” Lunden writes. “It would become my company, my work, my healing.”

This time-spanning kinship gives Lunden permission to move through the decades with sometimes dizzying speed as the definition of her illness, and the seriousness with which it is viewed by the public and medical community, evolves. The author’s careful entwining of memoir and reportage gives the book structure and a measurable timeline. Lunden relates that she had been suffering for a quarter century when, in 2015, myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (once dismissed as “yuppie flu”) was dubbed by experts at the Institute of Medicine as a “serious, chronic, complex and systemic disease.”

Decades of lived experience have already convinced Lunden that ME/CFS is truly what researcher Paul Cheney describes as a “multiple injury.” Pinpointing the genesis of her illness is less the point than tracking the gathering forces that contribute to its continuation. At over 400 pages, the book is epic in scope, but by using the parallels between her own story and that of Alice James, Lunden grounds her extensive research with an intimate tale.

An exploration of the stresses of modern civilization leads to the subject of toxic Victorian wallpaper and thus to the work of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and ultimately the way women are perceived by society as a whole. By the early 19th century, a male-dominated medical community had determined that the uterus of the so-called “angel in the house” all but guaranteed her mental and emotional instability. Absurd? Yes. But even more so is the revelation that, until the early 1990s, women were rarely included in medical studies. Lunden applies a similar rigor to unearthing the connections between the EPA and the oil industry. Terms such as “body burden” arrive on the page with the force of a punch as Lunden describes the American Petroleum Institute’s 1948 concession that “the only absolutely safe concentration for benzene is zero,” and we read on to learn that these chemicals were not regulated by the EPA until 1989. It is similarly shocking to find that, between 1981 and 1983, while under the watch of Anne Gorsuch (mother of Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch), the EPA lowered standards for an “acceptable” risk of cancer from one in a million to one in 10,000. This discounting of human life opened the door for the approval of the household use of permethrin, the insecticide encountered by Lunden at the outset of her illness.

Prepublication materials comparing Lunden’s book to Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) are not wrong. This is at times a tough read, but it’s that toughness that ultimately kept me engaged. As exhausted and frail and worn down as Lunden gets, she never ceases to find power in creating her own narrative. By inviting us into her chaos, she also invites us to participate in the quest for change. She ponders the 1892 death of Alice James on the threshold of the Progressive Era, when early efforts in unionization, corporate limitations, and environmental preservation, along with the rise of investigative journalism, helped make our country cleaner, safer, and more equitable. Unlike James, Lunden has found ways to manage her illness and, at times, has existed symptom-free, but like the goings-on beneath the bark of my eucalyptus, the human body is complex and ever-changing. So, too, our country and our world.

Toward the end of the book, Lunden offers hope in the form of action. Having found some relief in the retraining of her brain, an actual rewiring through consistent action, she asks us to consider the value of neuroplasticity in our own lives. We should rethink: Is there less we need? Is there more that we can do? How can we move our families, our communities, and our country in the direction of social justice rather than economic growth? How might we work together to make things better? “I don’t have it down yet,” Lunden writes. “I’m a work in progress. So are you; so are we all. And I, for one, will keep trying.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Tanya Ward Goodman is the author of the memoir Leaving Tinkertown (2013). Her essays and articles about travel, art, and the challenges and rewards of caregiving have appeared in numerous publications including The Washington Post, Luxe, Atlas Obscura, Variable West, and Statement Magazine.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Lesson of a Long Illness: On Ross Douthat’s “The Deep Places”

The conservative columnist’s memoir chronicles his struggles with Lyme disease.

When the Chronically Ill Go into Remission: Filmmaker Jennifer Brea’s Life After “Unrest”

Megan Moodie details her own experiences with chronic pain and illness alongside a critical assessment of Jennifer Brea’s documentary “Unrest” (2017).

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!