A Separation: Sheila Kohler’s “Once We Were Sisters”

Jean Hey looks at Sheila Kohler's new memoir.

By Jean HeyFebruary 22, 2017

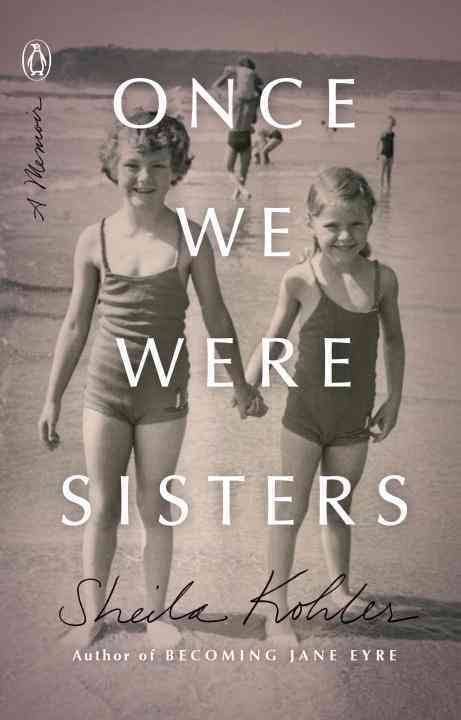

Once We Were Sisters by Sheila Kohler. Penguin Books. 256 pages.

SEVERAL YEARS AGO, Sheila Kohler gave a talk to MFA students at Bennington College on “Finding Your Material.” I wasn’t there, but a CD of the lecture was sent to me and the rest of the incoming class as an appetizer for the literary feast ahead. I listened to it with all the reverence of a student at the master’s feet. Kohler’s clipped South African accent was similar to mine — so familiar that I felt I knew her, that she was talking straight to me.

Early on in the lecture, she quotes from Elaine Pagels’s The Gnostic Gospels, a passage meant to be about life, she explains, but it could just as easily be about writing. Kohler reads slowly to let the words sink in:

Jesus said, “if you bring forth what is within you, what you bring forth will save you. If you do not bring forth what is within you, what you do not bring forth will destroy you.”

“The stakes are high,” she goes on. “You’ve got to have the courage to ‘bring forth,’ even when it may not be the easiest thing or even what you want to write about.”

What I didn’t know at the time was that Kohler’s only sister had died when they were both in their 30s. In novel after novel, in fact, Kohler has tried to keep her spirit alive, approaching the tragedy from different angles, in various disguises, trying to come to terms with her unintended role, searching for answers to the “what ifs” that haunt her.

Now in a memoir, Once We Were Sisters, Kohler addresses the topic head-on. The book is slender — in less restrained hands it could easily have been twice as long — each recollection laid out in vivid, unsentimental prose alongside telling family photos.

Kohler is a master of tension, and she has crafted a work that entices the reader not with the question of what’s going to happen — she reveals the circumstances of Maxine’s death in the prologue — but why. And how. How, with the advantages of wealth, education, and beauty, did the tender, compassionate Maxine end up dead on a deserted road at 39? How did those around her let that happen? And hardest of all, how did the author, who was closer to her than anybody, not see the tragedy coming and stop it?

This is painful territory, but Kohler refuses to shy away from even the most wrenching detail. She writes in short chapters, each scene fleeting but startling in its clarity, soon to be overtaken by another, and another. Sometimes her anguish spills onto the page, but for the most part she writes with a journalist’s detachment in the continuous present tense, as if the past is still alive and malleable — as if with a little effort she might be able to reach back and change the course of events. At the same time, she frequently reminds us of what is to come, as when, early on, Maxine visits her in a New Haven hospital after the birth of her first daughter:

She tells me about the young doctor she has met in Johannesburg. I am not sure how much she tells me that day, or even how I react to her words. I am unaware of their importance in our lives. I am preoccupied with my new husband, my new baby, and with the blood that flows from my own body. Much later, her children will fill in the blanks with words that ring with significance.

In one moment the author herself is bleeding, perhaps profusely — in the next she reminds us that, unlike her sister, she will survive. Right up to the end there is a restlessness in these pages, as there is in these sisters who, as young wives, rendezvous with one another all over Europe, in “beautiful places,” often abandoning their husbands and many children, because it is only in each others’ company that they feel fully themselves, fully seen, and alive.

¤

For the most part, Kohler’s narrative alternates between childhood with her sister and her life as a young wife and mother. It is a kind of “before” and “after” structure, divided by the first time Maxine mentions to her sister the man who will be responsible for her death.

Even though we initially see Maxine’s husband, Carl, through his wife’s adoring eyes, we know the role he plays in this story and he certainly looks the part: cold blue eyes, chiseled features, a flashing white smile. He is a man uncomfortable with conversation, who “buries his unease under a veneer of mockery.” He is also a brilliant cardiothoracic surgeon who performs heart transplants. The first mention of assault comes halfway through the book. When Kohler’s mother tells her that Carl beats her sister “black-and-blue,” Kohler remembers hearing about a butcher who received clemency for a brutal crime because of his line of work, and she asks herself: “What happens to someone who cuts into the heart and cracks the bones of the chest, day after day?”

And yet she shies away from her own question. She tells her mother not to exaggerate; a doctor would never do such a thing. The conversation is a tipping point — a moment when Kohler could intervene and perhaps change the trajectory of their lives, but instead chooses to do nothing.

She has her reasons: she has her own rocky marriage to deal with, and she is struggling to teach her deaf daughter to speak. But Kohler doesn’t linger on excuses. Her quest is to find out what caused her to look the other way. What elements of her and her sister’s past — they grew up white, privileged, and protected in apartheid South Africa — made them so forgiving of the men they married and so quick to blame themselves?

She lists the particulars of her family’s estate with matter-of-factness, as if it were quite normal to grow up on a property with a nine-hole golf course, a swimming pool, a tennis court, an orchard, and acres of wild veldt. Normal, too, for the house, the grounds, and all the trappings of affluence to be maintained by an “army” of black servants.

Kohler also presents her mother’s indolent life as typical of South Africa’s upper classes — shopping sprees, long naps, evenings of heavy drinking with her own two sisters — but we glimpse another view through the children’s white nanny, Miss Prior. Kohler is eight when her father dies and Miss Prior is let go. As she walks out the door, she says, “These children would be better off in an orphanage.” And yet parental neglect allows the sisters to spend delicious, uninterrupted hours playing outside, unconstrained by adults. Some of the book’s lushest passages are descriptions of days spent in the Africa of their backyard:

[H]ow freely we roamed the land together, half naked, as children: bare-headed, barefoot, swimming in the big pool, picking armfuls of bright flowers and entwining them in our hair, around our ankles and wrists; gathering oranges and lemons, which fell at our feet; plucking warm sour tomatoes from the vine, bending over to eat them, the juice squirting into our mouths and onto the earth; climbing up into the dark, cool leaves, hiding in our safe places, the jacarandas, the lychee tree, which spread its heavy branches to the ground like a canopy at the bottom of the garden; stuffing the sweet fruit into one another’s mouths.

Of course there is a dark side to paradise. Black convicts are brought in to landscape and weed the garden, and Kohler and her sister stand and stare at them until they are told to “move along.”

Are these men transgressors of apartheid, or real criminals? How to discern the difference under apartheid in the 1950s? The core of Kohler’s South Africa is rotten, but nobody in the family talks politics, least of all “Mother,” as she is always called. To question the system would be to question their lifestyle, which Mother feels she has earned by marrying Kohler’s father, a rich timber merchant 20 years her senior. What matters is to maintain a veneer of gentility, a glaze of propriety, to wear the right clothes and adhere to etiquette, to make sure the servants polish the silver and wear white gloves and serve from the left. For the children, what matters most is to be in one another’s company, and to try not to be scared when Mother’s words slur and an invisible witch overtakes her.

The only reliable adult in the house seems to be John, a strong and silent Zulu, who performs his domestic tasks with dignity and without judgment. It is John who brings young Sheila a birthday cake when she is quarantined with scarlet fever. And it is John who carries Mother to bed when she passes out. At one point Kohler questions how Mother viewed this man who devoted himself to this family: “What is he to her? A child? Half a person? An animal? A eunuch? A saint? A human polisher?”

It is no wonder that Kohler leaves home as soon as she can. Her stated reason is to learn French, which Mother accepts on the basis that it might improve her chances of landing a suitable husband, preferably an English lord. Her real reason is not so much to escape apartheid — at 17 she has never taken a political stand — but to free herself from a suffocating house of women, including her narcissistic mother. She writes, “I have no idea who I am or even what I believe, and feel it necessary to go elsewhere, to another country, a strange land where no one speaks English, to find out.”

Who, then, emerges? A writer, a lover of the arts and travel, a seeker of Truth. But above all, a sister. Despite the cruelties she and Maxine suffer in their marriages and their strange childhoods, they have each other. That is, until they don’t.

Ironically, it is only after Maxine’s death that Kohler fully comes into her own. Following the tragic “accident,” she turns to writing novels — first as an attempt at revenge, then to keep her sister close and safe, and to look for answers to the silences and secrets that seem to envelop her family. Losing Maxine also awakens her to the state of her own marriage, and the realization that she must leave it.

To my great disappointment, Sheila Kohler was no longer on the Bennington College faculty by the time I got there. Still, I had her lecture — in which, after urging the audience of budding writers to “bring forth” what’s inside, she shares the advice of an author friend: Set out to break the reader’s heart. “You may also break your own heart in the process,” Kohler says. That, she insists, is part of the process, too.

With this powerful memoir, Sheila Kohler may not have managed to save her sister, but she has brought her back to life. I imagine her heart broke again and again in the course of the writing — but then, a broken heart can release compassion, not only for others, but also for oneself.

¤

LARB Contributor

Jean Hey was a journalist in South Africa before immigrating to the United States. Her essays have appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The Plain Dealer, Chicago Tribune, Solstice Literary Magazine, The MacGuffin, and Arrowsmith Journal. She holds a dual-genre MFA in fiction and nonfiction from Bennington College and recently completed a collection of memoiristic essays about immigration and identity.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Land Down Under

Jean Hey reviews David Francis’s novel "Wedding Bush Road."

South African Feminism, Lady Gaga, and the Flight Toward “Queer Utopia”

As a fundamental human desire, the power to imagine new worlds that explode existing ones through gender performance and symbolism is universal.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!