A Life in One Day

Kate Wolf on Christa Wolf's "One Day a Year: 2001-2011."

By Kate WolfNovember 19, 2017

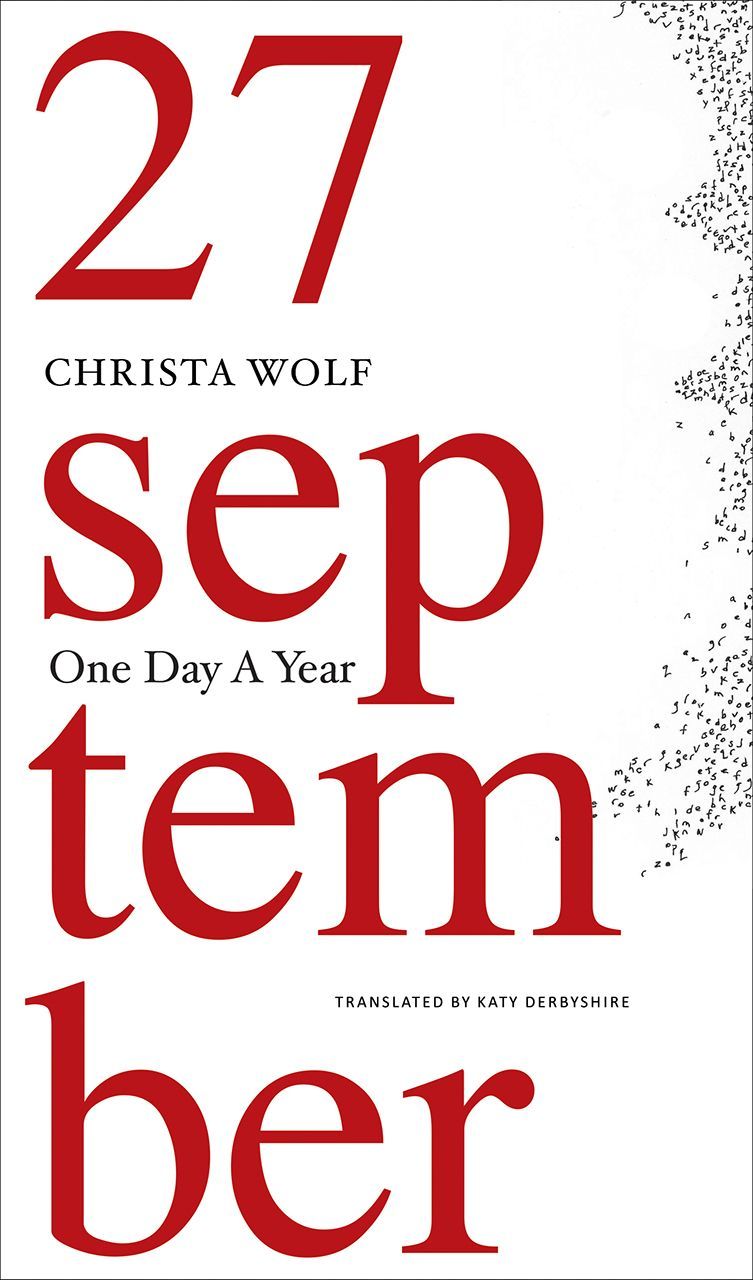

One Day a Year: 2001-2011 by Christa Wolf. Seagull Books. 128 pages.

HOW BEST to capture life in writing? “Is life identical with time in its unavoidable but mysterious passage?” the German writer Christa Wolf asks in the introduction to her 2007 book, One Day a Year. “While I write this sentence, time passes; simultaneously a tiny piece of my life comes into being — and passes away.” Elsewhere, Wolf described life as being but a series of days. And in One Day a Year, translated by Lowell A. Bangerter, and its recently published companion volume, One Day a Year: 2001-2011, translated by Katy Derbyshire, life is specifically a half-century’s worth of September 27s.

From 1960 until her death in 2011 at the age of 82, Wolf dutifully recorded every September 27. The tradition began in response to a call for an international record of the day by a Moscow newspaper, itself based on a project started by Maxim Gorky in 1935 called “A Day in the World,” meant to juxtapose life in and outside of the Soviet Union. Wolf, a citizen of the German Democratic Republic until reunification, was one of a number of writers invited to respond. Her September 27, 1960, begins with preparing to take her younger daughter Tinka to the doctor for a sore foot. Tinka’s birthday is the following day, and Wolf remembers back to four years earlier when she was pregnant and awaiting her arrival. Out in the city, she observes small signs of destitution, like the old women in the doctor’s office discussing the cost of a sweater, or an elderly couple who has spent all their money on shopping and cannot pay for the streetcar. At home, she sorts through the mail and eats lunch. She attends a meeting for a worker’s brigade at the nationalized railroad car factory, research for her debut novel Divided Heaven. Later in the evening, she burns the cake for Tinka because the batter is too high in the pan, and she becomes aggravated. She listens to a violin sonata with her husband, Gerd. At some point, she writes notes for the pages we read. Lying in bed before sleep, she is struck by the way ordinary days like the one that just passed cohere into a life, into some kind of narrative, only through the “unswerving effort” that “gives a meaning to the small units of time in which we live.”

In the One Day a Year collections, Wolf constructs this meaning through the brilliant yet deceptively simple formal constraint, as well as a keen eye for the many different facets of existence. She’s able to paint the intimate details of her life against a larger political and intellectual backdrop of which she herself, as the preeminent writer of East Germany (also celebrated in the West and revered by contemporaries like Günter Grass), was very much a part. But though politics and other aspects of public life inevitably feature in these entries, Wolf is most concerned with tasks of writing, with reading, family, and domestic chores or pleasures, such as what her husband Gerd will cook for lunch, how long a nap she has taken, and what she watched on television.

In the last decade of Wolf’s life, covered in One Day a Year: 2001-2011, she writes increasingly of her ill health, of aging, faltering memory, and the specter of death:

At eight I get up and go the bathroom before Gerd; it’s usually the other way around. Morning rituals, which automatically raise the questions of how much longer? How many more times? [2007]

Or more prosaically, from a few years earlier:

So now the routine after getting up (whereby I secretly check whether the fibrillation might have passed overnight; but I can’t tell, you can’t feel it in your pulse). Showering, etc. The Innohep injection I have to give myself until the Falithrom tablets have brought my blood coagulation value below 2 — whatever that means. A slice of bread with vegetables from the organic food store because I want to lose weight as usual. A cup of tea. My various tablets. [2004]

Part of what makes Wolf’s entries so fluid and lifelike is the way they wend from the present to the past, from the realm of dreams and books to the immediacy of something like making a salad dressing or bodily aches and pains, from a distillation of the day’s mail and telephone calls to disturbing events captured in newspaper headlines. (Perhaps because Wolf was already in her early 70s at the turn of the century, there is no mention of the internet.) The daily collision of the banal with the exceptional is a familiar motif of modernism; so, too, is the anatomy of the single day, something Wolf explored in novels like the Accident: A Day’s News, which follows a writer in the German countryside on the day of the Chernobyl disaster.

But while they may share some stylistic overlap with her other writing, Wolf’s assembled days don’t work like fiction, or even like a regular episodic diary. They don’t sustain any larger plot, nor do they usually resolve in anything other than sleep. In contrast to a circadian novel like Ian McEwan’s Saturday, which Wolf happens to be reading one September 27 and critiques for feeling forced and not spontaneous (she chafes, for instance, at how McEwan decides to deliver, via flashback, his main character’s entire life story), Wolf’s entries are fragmentary and mostly uneventful. One Day a Year takes an arbitrary framework and makes it feel significant through commitment, repetition, and time. Wolf refers to these records as “pillars” for her memory.

One of the more gripping entries in the recent volume does come in proximity to a major occurrence: on September 27, 2001, Wolf is reeling from the World Trade Center being blown up 16 days earlier, and the looming war in Afghanistan. The phrase “a rip in the fabric of time” echoes in her head upon waking. A kind of dread has set in. The feeling recalls for her other irredeemable, cataclysmic moments she’s witnessed in history: the beginning of the war in 1939; being expelled from the German town of Landsberg, where she was born, after it was seized by the Red Army in 1945; the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. The enormity of recent events gives the day an intense focus, pushing it in the direction of essay (indeed, it was published as a standalone piece in 2002). Wolf considers the meaning of Western civilization, “the alleged target of the attack,” with skepticism: “Everyone appeared to know what our civilization is. I resort to dictionaries.” She questions whether “Greek philosophy, the monotheistic religions, the Enlightenment’s belief in reason” have lost their efficacy in the Occident under the “terror of the economy,” or if perhaps they’ve just eroded from within: “And have not more and more people sensed this civilization of ours is hollowed out and empty […] Have we not more and more frequently heard the words: it can’t go on like this?” At the same time, looking at a photograph of Bertolt Brecht against the midtown skyline placed on her manuscript stand, she is reminded of how crucial New York City was to his and other German émigrés’ escape from the Nazis in the 1940s.

Ultimately, though, she is weary of war, and pessimistic. She receives an article in the mail from a friend castigating anti-American sentiment by German intellectuals, which she regards dubiously, as she does the idea circulating in the media that the events of September 11 will somehow bring about a unified front between East and West Germany. Throughout the day, she finds solace in reading E. L. Doctorow’s City of God, with its pre-9/11 premonition of catastrophe and returning to it again before bed, she ends with an ominous quote by Ingeborg Bachmann: “Harder days are coming.”

Mention of the US occupation of Iraq recurs in subsequent years alongside discussions of German politics, but as Wolf ages a decade over the course of the 10 single days portrayed in the book, she seems decreasingly engaged with the outside world. Her 2008 entry is written from the hospital, where she has gone for a complicated knee joint operation, and because of her difficulty walking she is often confined to her Berlin apartment. Wolf’s role in German public life also shifted dramatically following the dissolution of the GDR (an event touched upon in the previous One Day a Year volume). She had a heart attack shortly before the wall came down and experienced a deep depression afterward, exacerbated by a number of public controversies. The first concerned a fictional account of her surveillance by the Stasi in the short story collection What Remains, which Wolf originally wrote in 1979 but kept from publication until 1990. She was criticized for not publishing the collection sooner, when its revelations of harassment by the government might have served as a pointed critique, and carried more political weight.

Wolf wrote about the second, larger scandal in her last novel, City of Angels, which she struggles with throughout One Day a Year, and which deals explicitly with the failing, or suppression, of memory. It’s based in part on Wolf’s revelation late in life that she worked with East German intelligence for a few years in the early 1960s as an informal collaborator, reporting on other writers. She claimed, to her own incredulity and shame, not to recall much of the experience, feeling that she must have repressed its more unpleasant aspects. The need to record the details of life in order not to forget them was something Wolf wrote often about, but after reading her “Perpetrator File” and the voluminous documentation of her own surveillance, she found that particulars alone don’t always relay the full story. When the narrator in City of Angels is shown the files that the Stasi has kept on her, she feels “soiled.” “Even if the facts that the observers reported on […] were true,” she writes, “even then, not one of them matched how I felt. If there’s anything I learned in reading those reports […] it’s what language can do to the truth. Those files were in the language of the secret police, completely incapable of capturing real life.”

One Day a Year was Wolf’s attempt to capture what the Stasi could not: “real life,” the texture of daily existence, its mushy transience and essential subjectivity. Rather than finely drawn portraits or expertly crafted anecdotes, the precise geometry of the book lends itself to a compelling way of looking at time, a layering of days that are sometimes barely discernible from one another. For Wolf, it wasn’t that the structure of writing was able to bring back the time that had passed; instead, it was the thing that made living possible. Writing could be a way to cut through circumstance and ideology, an occasion for something of the self to coalesce on the page again and again. Her character in City of Angels says as much looking over an old notebook:

I woke up early, out of a morning dream and heard a voice say: Time does what it can. It passes.

Those were the first sentences I wrote down in the large lined notebook that I had taken the precaution to bring with me and had placed with my notes, which I can now refer back to. In the meantime, time has passed, the way my dream laconically informed me it always does — which was, and is, one of the most mysterious processes I know and one that I understand less and less the older I get. The fact that rays of thought, looking back into the past and looking ahead into the future, can penetrate through the layers of time strikes me as a miracle, […] because otherwise, without the benevolent gift of storytelling, we would not have survived and we could not survive.

Wolf’s last September 27 is brief. She mentions her mounting pain, her repeated circuit between the bed and the bathroom, her doubts about how much longer she can go on. She reads a book on Borges, eats some egg and bread, complains about her nurse, and finishes mysteriously with an unexplained quote from “BZ”: “It’s going to be noisy over the Müggelsee” (a lake outside of Berlin). Then, just as in life, we turn the page and the book is over.

¤

LARB Contributor

Kate Wolf is an editor at large for the Los Angeles Review of Books as well as a host and producer of its podcast, The LARB Radio Hour. Her short fiction, criticism, interviews, and essays have appeared in exhibition catalogues and publications including Bidoun, Bookforum, Art in America, The Nation, East of Borneo, Public Fiction, X-TRA, Night Papers — an artists’ newspaper she co-founded and edited with the Night Gallery in Los Angeles from 2011 to 2016 — and on KCRW and McSweeney’s program, The Organist.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Shipwreck of History: Bertolt Brecht’s “War Primer”

Roy Scranton reviews Bertolt Brecht’s “War Primer.”

Streetwalker

Kate Wolf visits Lauren Elkin's "Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice, and London."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!