A Humane Remove: Nick Drnaso’s “Sabrina”

Nick Drnaso makes comics of acute psychological realism that approach their subjects from an almost anthropological remove.

By Greg HunterJuly 14, 2018

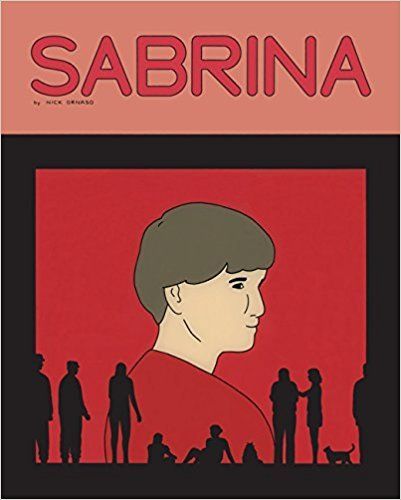

Sabrina by Nick Drnaso. Drawn and Quarterly. 204 pages.

EARLY IN Nick Drnaso’s graphic novel Sabrina, two nondescript men greet each other in a nondescript train terminal. Old friends from their teenage years, Teddy and Calvin are reuniting under tragic circumstances, which the book reveals in the pages that follow. Their first exchanges are clipped and one-sided, as Calvin plays a one-person welcoming committee and feels out the depth of his friend’s damage. Teddy is visiting from Chicago after the disappearance of his girlfriend, Sabrina, and a breakdown he suffered afterward.

Teddy displays little emotion — he’s subdued on the surface — and Drnaso lends his pages the same qualities. Muted grays, blues, and beiges dominate the drive to Calvin’s Colorado condo. Here and elsewhere, Drnaso avoids shading and hatching, and he forms his characters’ expressions with as few lines as possible. Each page devotes space to silent beats and to the small motions of life, with Drnaso working on a literally small scale — he often includes more than a dozen panels per page. This distanced sensibility extends throughout the novel and throughout Drnaso’s body of work.

Drnaso makes comics of acute psychological realism that approach their subjects from an almost anthropological remove. An easy comparison is Chris Ware, with his clean-lined compositions and stories of the lonely, the stunted, and the mistreated. But unlike Ware, who enacts these scenarios with complex, formally dynamic layouts, Drnaso’s stories are tidy, unadorned, and judicious in their limited emotional range. The effects of this approach, and possible explanations for it, are numerous.

An uncharitable take on Drnaso would go something like this: the distance in his comics is a way to safeguard the work, even the artist’s ego. Such a measured style reduces the risk of being perceived as sentimental. It avoids any flourishes that may be seen as overreaches or miscalculations. It’s an eminently — even excessively — adult and respectable approach to comics fiction.

Drnaso’s previous book, Beverly, did not encourage quite so cynical a reading. He brought a depth of observation to the collection, in addition to a rigorous adherence to his aesthetic. The book’s stories — understated vignettes about Midwestern confusion and alienation — suggested too much interest in the lives of others for Drnaso’s mutedness to read as a shield. And yet, conveyed through such a disciplined approach, the stories did risk being appreciated more for their formal precision than for their insights into people.

Another take on Drnaso is that his approach reveals, and rewards, a kind of trust. It provides for a range of feelings and allows readers to bring themselves to the work, no authorial hand-holding needed. In this understanding, the distancing effect these comics produce means that readers’ powers of empathy determine how they experience a story, with all the uncertainty that this entails. At its best, Drnaso’s work encourages readers — more thoroughly than might art with more explicit rendering of its characters — to recognize the interiority of other people. We pause, reflect, and introduce more of ourselves.

This reading fits Beverly, but it fits Sabrina better still. Drnaso’s second book contains one sustained story, and whatever risks there are in an artist like Drnaso attempting long-form fiction — monotony, repetition fatigue, et cetera — the novel suits him. Sabrina engages with the same characters, concerns, and tensions for 200 pages without denying readers interpretive latitude. And between Teddy’s inarticulable pain, Calvin’s interpersonal shortcomings, and the struggle of Sabrina’s sister, Sandra, to find catharsis, Drnaso also explores the challenge of expressing painful emotions on a plot level.

¤

Some weeks after he moves to Colorado, Teddy learns that Sabrina has been murdered. The news reaches him at the same time it reaches Calvin, Sandra, and the rest of the world. The killer, a young white male who used to visit “body-building and men’s rights” sites, filmed the murder before taking his own life. Sabrina’s death soon becomes a national story, with the footage achieving viral status in the darker parts of the internet.

The story sees Calvin struggling to help Teddy even prior to news of the killing. A member of the Air Force with an IT job and a wife who recently left him, taking their daughter with her, Calvin is by his own admission “oblivious and detached.” After the news of Sabrina’s murder breaks, he is drawn into the viral spectacle surrounding it. Fringe online elements conclude that the killing was a false-flag operation and that Calvin is a crisis actor. Already adrift, he’s beset by new forms of confusion. Sandra, meanwhile, cycles through ways to occupy her time and give structure to her grief. And Teddy finds a coping strategy that threatens to damage him further: he becomes a regular listener of Albert Douglas, a radio host who perpetuates notions of fake mass shootings and other “globalist” conspiracies, including — eventually — the idea that Sabrina’s death was staged to agitate the public.

With all this in mind, one benefit of Drnaso’s aesthetic is that Sabrina never reads as though it’s sensationalizing the traumas of its characters. Nor does it read like a book overeager to capture The Way We Live Now. With Drnaso’s mutedness comes a kind of decorum, which is crucial for the success of a work like this. Sabrina — drawn in advance of events like the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting — anticipates the increased acceptance of crisis-actor theories as a response to the killing of young people. And while it’s a cold comfort, the book provides a space apart from the internet in which to contemplate how people process tragedy through the internet — including the failures of empathy that such processing often entails.

Sabrina does sometimes arrange too neatly Teddy’s entry into the thrall of paranoid talk radio. For instance, while staying at the home of an Air Force member Teddy hears the host, Douglas, suggest that the US military helps manufacture crises. And in a broadcast that occurs directly after Teddy has discovered Calvin’s cache of emergency food reserves, Douglas warns that global conspirators might soon shut off the public’s access to food.

But although Sabrina can be heavy-handed in choreographing such developments, it does capture, in a subtle, effective way, the allure of Douglas’s mindset to a vulnerable person. Several times, Drnaso alternates panels of a radio playing Douglas’s show and panels of Teddy listening — a simple formal gesture that suggests the intimacy Teddy finds in the program, the show’s inviting simulation of a human-to-human connection.

If Drnaso positions readers at a remove from Teddy, Calvin, and Sandra, readers spend the most pages with Calvin, and this extra exposure to his moods and tics can give one the feeling of knowing him best by book’s end. Sabrina gives the fewest pages to Sandra, and unsurprisingly she remains the most remote of the principal characters. But in the case of all three, Drnaso resists internal monologues or other means of showing readers the world through his characters’ eyes.

The mutedness of Drnaso’s approach allows for a limited amount of explicit information about Sabrina’s main characters and their dilemmas, and even that information arrives in installments. For instance, readers see the bareness of Calvin’s condo before they learn of his wife and child’s departure and see several scenes of him at work before learning what his duties are. With secondary characters, Sabrina shares even less. And as Sabrina’s murder starts to command national attention, this remove generates increased uncertainty about the principal characters’ safety and everyone else’s intentions.

But on select occasions — and in a few of the book’s most gripping scenes — Sabrina uses its rigid omniscience to unsettle readers’ sense of what’s real, or at least what’s worth worrying about. Drnaso generates a real sense of tension and danger around his characters’ online interactions. Strangers message Calvin, convinced he’s party to a vast conspiracy, and urge him to go public. Neither he nor the reader has any real context for how dangerous these people are, but one persistent emailer even learns the new address of Calvin’s wife and daughter. Drnaso has a frightening facility with the voices of these online strangers, their mix of conviction and dysfunction: “The rest of the world may have forgotten about you, but not me,” the most aggressive emailer, Truth Warrior, tells Calvin. “A lot of guys only dig into a subject until something new comes along […] I prefer the more obscure players, people like you, you are on the periphery. Maybe you weren’t directly involved, but you can certainly help us uncover who is responsible and bring them to justice.”

The intensity of Sabrina escalates as Drnaso puts his principals in physical proximity to people who may hold these views. Late in the book, Teddy goes looking for a lost cat, becoming a more active participant in his own life than he’s been for most of the story. It’s a rare cause for optimism, undercut by the appearance of an imposing bald man in a black hoodie. The man offers Teddy a ride, Teddy accepts, and Drnaso’s formal choices give what follows a concentrated dread. As the two men drive around in the dusk, making small talk, darkness overtakes Drnaso’s muted palette. His small panels heighten our sense that we lack information about the characters and the situation. Nothing in the scene is a foregone conclusion, but the experience — the uncertainty, the onset of fear — makes the texture of Calvin, Teddy, and Sandra’s lives more palpable than before.

¤

With its invocations of education and taste, or the lack thereof, Sabrina may prompt discomfort of a different sort. In addition to Drnaso’s talent for mimicking the voices of online hostiles, he has an instinct for the right detail to convey a certain white, middle-American drabness. “I’m a sucker for micro-brews,” Calvin tells Teddy during an early effort to play host, adding, “I like that brand. They have cool packaging.” This kind of guilelessness is a minor preoccupation of the book. A later scene, in which Sandra attends an open mic night, sees multiple parties sharing bland sentiments like, “I’m pretty well-liked at my job. I’m kind of the comic relief.”

It’s possible that Drnaso intends lines like Calvin’s micro-brew comments to read at face value. It’s more likely that he’s wringing tension from a character saying something banal without knowing it. If the latter, then he’s successful. But these moments also create a tension between the sociological precision needed to tell an authentic story and the otherwise humanistic bent of this particular story.

Here, as with Drnaso’s larger aesthetic, an uncharitable reading is available: Drnaso, the Ivan Brunetti protégé with a blurb from Zadie Smith, is condescending to normie culture from a position of distinction. But here too, Sabrina resists that reading. Drnaso gives readers just enough latitude to mistake the distance from which he operates for scorn. Panel to panel, within discrete scenes, there’s not always some unmistakable endorsement of a character’s personhood to counterbalance details about the character’s lack of refinement. But overall Sabrina devotes too much attention to its characters’ lives, their pain, and their futures to leave readers with an impression of Calvin or Teddy only as a cutout in some diorama of middle-class malaise. We might find Calvin’s words on craft beer corny, but that doesn’t mean we should withhold empathy.

And more often than not, Sabrina, with its distance and its understatement, succeeds in eliciting empathy from readers. Sometimes this means Drnaso including subtle signs of Teddy’s obvious pain and helplessness in sequences designed to make the pain resonate. One early scene, the first in which Teddy explicitly articulates some of his anguish, barely shows his face at all. He’s leaning over on a couch, or seen from a side view, or both. In other panels, his shaggy hair forms curtains around his features. Calvin — seated next to Teddy, in a Snuggie — has to work to understand his friend’s experience, and so does the reader. The scene details both the pain the character is feeling and the difficulty of engaging with it.

Drnaso undertakes a different gambit by making Calvin a member of the armed forces, which means some readers will be starting from behind as they cultivate an empathetic view of the man. There’s a plot-level benefit to this, of course. As Teddy goes deeper into the world of Douglas’s fringe conspiracies, Calvin’s occupation makes him a figure of suspicion. But Drnaso manages to balance understated critiques of the military as an institution with empathy for Calvin as a person who inhabits it.

Nor is Drnaso unwilling to let his characters look ridiculous. But he does so in ways that are compatible with their basic dignity. Some of the book’s most memorable moments balance multiple tones at once, including goofiness. For instance, Drnaso frequently shows a character or characters in their underpants to convey vulnerability. It’s the book’s least subtle piece of visual shorthand, but still an effective one.

A poignant moment early in Teddy’s stay with Calvin, for instance, finds Teddy undressed and screaming, upright in a corner of Calvin’s guest room after a nightmare. Calvin, woken by his friend’s cries — and also nude save for a pair of undies — rushes in. Drnaso neither plays this moment for laughs nor belabors its harsher elements. Teddy wears nothing but underpants in many later scenes, resembling both an adult baby and a man lost at sea. A particularly moving sequence comes as Calvin returns home from an Air Force shift with a sack of fast food. Teddy, lying in bed in his white briefs, has trouble moving, much less eating, and so Calvin holds a burger to his mouth as if nursing his grieving friend. It’s a moment of awkwardness, absurdity, and tenderness all at once.

The distance Drnaso observes as a storyteller doesn’t mean that he gives readers a blank canvas that they can fill at will. On the contrary, his careful choices about character and form set the range of likely responses to his work. The range is wide nonetheless. It’s on Calvin to stand by Teddy, even if he can’t grasp Teddy’s interiority. It’s on Teddy to resist a harmful understanding of the world, even if it’s an alluring one. And it’s on readers to stay with, even animate, these characters, no matter how well or poorly they relate to them. In exchange, Drnaso shares a story that is — sometimes despite appearances — surprising, relevant, and humane. Sabrina is never loud in its urgings toward empathy, but it rewards people willing to do the work necessary to achieve it.

¤

LARB Contributor

Greg Hunter is a writer based in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He edits graphic novels for young readers and has contributed comics criticism to The Comics Journal, The Rumpus, and other publications.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Creating a Comics Canon

Russ Kick’s "The Graphic Canon of Crime and Mystery" is, for now, the most sustained anthology of comic art in the English language.

Confronting Uncertain Worlds: Comics with Young Female Protagonists

A review of two recent comics for young adults.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!