A Happy Monster

Charles Hatfield ventures into "Hellboy's World" by Scott Bukatman

By Charles HatfieldSeptember 4, 2016

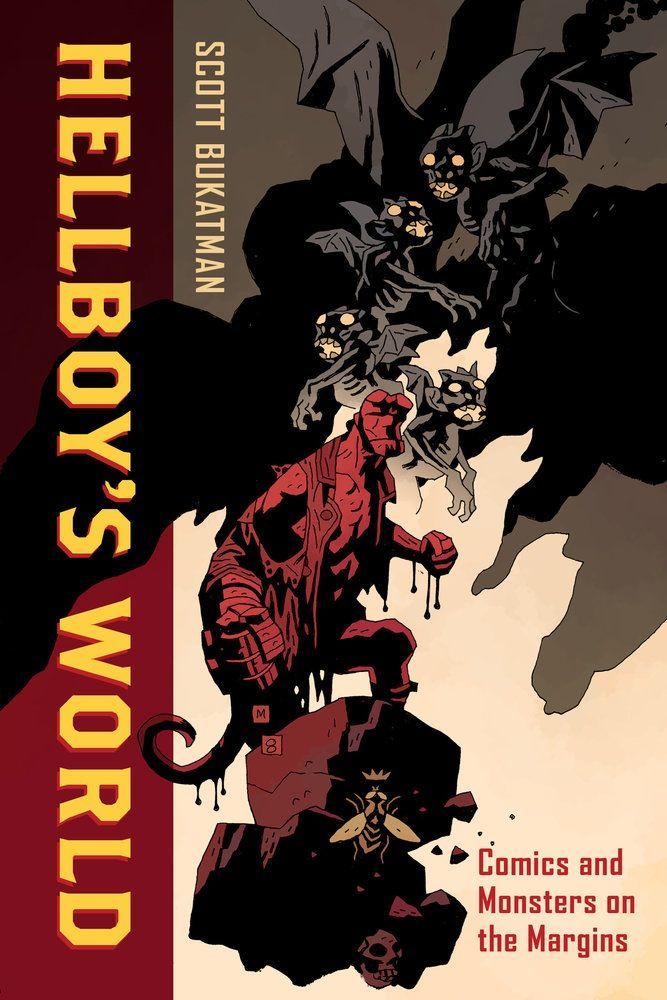

Hellboy’s World by Scott Bukatman. University of California Press. 280 pages.

HELLBOY DIED five years ago. His adventures came to an end a little over three months ago. In between, he observed his 20th anniversary.

If this makes no sense to you, don’t worry. Hellboy has a hard time making sense of it himself. He’s a demon who doesn’t want to be a demon. He’s a walking omen who doesn’t want to think about the future. The course of his life has never run smoothly. Depending on when you encounter him, he is old, he is young, he is alive and kicking or he is dead, dead, dead. Always he is stubborn, grumpy, and laconic: a demonic tough guy of few words. This holds true on either side of the veil, for in Hellboy’s world, death is just a change of state. These are comic books we’re talking about, after all.

Hellboy, monster-hero, is the brainchild and handiwork of writer-artist Mike Mignola — a singular creative presence in comics whose style has practically become a brand. Hellboy’s personality and destiny are effects of style. His ethos is written in his looks. He is a devil with skin of blazing red, a right hand of stone, and two stumpy, filed-down horns. A splendid, cockeyed vision, he recalls Jack Kirby’s great comic-book monster-heroes, The Thing and Etrigan the Demon, but he is no mere pastiche. He is the Mignola Effect personified. His adventures are graphic as well as literary excursions: a compound of chiaroscuro; brash, angular abstraction; smothering atmosphere; and minimalist storytelling that never reveals more than it has to. Steeped in this dark, brooding aesthetic, the Hellboy cycle of comic books-cum-graphic novels began in 1994, and reached an end of sorts this summer with the final issue of Hellboy in Hell, an underworld odyssey set after the hero’s death — but no less lively for that.

The sheer energy of the Hellboy comics, the delights they offer to readers, and what they may reveal about comic art in general are the subject of Scott Bukatman’s new monograph Hellboy’s World, a compact but disarmingly handsome volume that is likely to appeal to readers well beyond the research libraries that academic monographs usually reach. Hellboy’s World promises Mignola’s brainchild an afterlife of a different kind, in university classrooms, in academic comics studies (a mushrooming field), and on the bookshelves of brainy comic fans with an appetite for self-directed study (also a sizable demographic). Happily, Hellboy’s World doesn’t seek to elevate its subject to some remote plane of disembodied thematic analysis, but instead seeks to understand Bukatman’s own pleasure in the Hellboy comics, and to explore what makes those comics, and comics in general, intimate spaces of dizzying imaginative play. Hellboy’s World is a very brainy encounter with the visual and material pleasures of the comic book as readable object.

As a whole, the Hellboy cycle encompasses scores of stories — some short, some long — set in the same monster-haunted, doom-wracked world. All these stories have been written, co-written, or overseen by Mignola, but all of them are also collaborations of one kind or another. Some parts of the cycle are branded Hellboy, while others are branded with different names and follow different heroes: B.P.R.D., Abe Sapien, the deliciously named Lobster Johnson, and lots more. All told, these stories make up a baroquely layered shared world, a vast, sprawling web of narratives. Mignola set the terms of this world, and has drawn many of the stories himself, but a host of other artists (notably including Guy Davis, Duncan Fegredo, and Richard Corben) have leant their hands and visions. Co-writer John Arcudi (B.P.R.D.), editor Scott Allie, and publisher Dark Horse have also been important guides and supports, helping to grow Hellboy from one title into a teeming “Mignolaverse.”

The core of the Hellboy mythos, however, is Mignola’s near-solo work, written and drawn by him in spurts over the past 22 years, a dotted line of comic book miniseries and one-shots. These stories, most of them collaborations with the superb color artist Dave Stewart, are the real template for the Mignolaverse. They offer a blend of raw cartooning, elegant design, pulp revivalism, superhero action, Lovecraftian weirdness, and oddly personal forays into folklore, mythology, and legend. If Hellboy and its myriad sister titles together make up a cosmological horror-fantasy epic echoing Lovecraft, then Mignola’s solo work supplies the beating heart: a crypto-autobiographical series of increasingly dreamlike and abstracted meditations that manage to be high-spirited and deeply melancholy at the same time. That complexity of tone is one of the things that Hellboy’s World sets out to understand.

How might we read comics page? Bukatman examines this one at length. From Mike Mignola (story and art), Dave Stewart (colors), and Clem Robins (letters), “The Island” (2005), Hellboy: Strange Places (Dark Horse Comics, 2006). Hellboy copyright © and trademark of Mike Mignola.

Hellboy the comic manages to hit a sweet but damned hard-to-define spot between blustering adventure and aesthetic delectation. Loyal Mignola readers don’t read for transparency and the straightforward telling of yarns (though there are yarns aplenty, knotted and complex). They read for the experience, of course. One hallmark of a great comic is its capacity to draw readers into the internal world of a creator: a personal microcosm defined by the aesthetic and handiwork of an artist. For some years now, Robert Fiore, a critical stalwart at The Comics Journal, has been arguing as much: a comic works when it offers a vivid “Experience of Comics,” which is not to be defined solely in terms of literary merit but rather entails “inhabiting the subjective world the cartoonist creates.” By this logic, comics pages are not to be looked “through” in order to grasp the paraphrasable essence of a story, but instead to be looked at and luxuriated in. Scholar Jared Gardner, in his indispensable 2011 essay “Storylines,” has pointed out that the comics medium tends to refuse transparency in favor of making visible, and delighting in, its own devices. Comic art “does not offer the possibility of ever forgetting the medium,” Gardner asserts, but rather “calls attention with every line to its own boundaries, frames, and limitations — and to the labor involved in both accommodating and challenging those limitations.” That is, comics never render their own apparatus, or the comics reading experience, invisible. Bukatman seems to agree, arguing that comics may be absorbing but are not perceptually “immersive” in the same sense as is cinema. Rather, they must be “continually performed” by the reader. This performance — this pleasurable, often self-aware labor — Bukatman suggests, is the thing that makes comics engrossing. Hellboy’s World delights in the self-reflexivity and opacity (as opposed to transparency) of its medium, in the aesthetics of the comics page, the spread, and the total book. Bukatman identifies and builds outward from that delight.

More specifically, Hellboy’s World builds its argument upon Walter Benjamin’s observations about childhood reading and the nonlinear, extra-semantic pleasures of image and color in children’s books (we’ll come back to this, below). Further, invoking Stan Brakhage’s notion of the young child’s “adventure of perception” in a dazzling, as yet unnamed (therefore untamed) experiential world, Bukatman argues that the comics medium offers “a heightened adventure of reading” in which the reader constantly performs “syntheses of word and image, image sequences, and serial narratives.” This, he says, enables the medium to “exceed the rationalism” of the linear and grant readers “access to other worlds [and] to other modes of reading.” It is this spirit of adventure — the quiet, sedentary, but deeply enthralling adventure of diving into a book and bringing it to life — that Hellboy’s World celebrates.

Bukatman does not engage in plot synopsis, and downplays character and thematic analysis, instead digging into Mignola’s aesthetic strategies. Readers unfamiliar with the byzantine ins and outs of Hellboy’s life will find a lot in Hellboy’s World to think about, but they will also still find surprises in the comics should they go on to read them afterward. Yet for a study professedly uninterested in literary interpretation, Hellboy’s World turns out to be surprisingly literary, because it is invested in, one, the idea of bookness, as manifested in the material and sensual appeals of comics as books; and, two, the feeling of bookishness, that is, the feeling that Hellboy’s world is a devoted reader’s world, constituted by myriad intertextual references and by the sense that reading itself is an almost arcane study.

In fact, Hellboy’s World is among the most literary monographs to have appeared so far in comics studies. Observing that comics culture “venerates books as objects,” Bukatman argues that Mignola’s work in particular is invested in the idea of the book: Hellboy is besotted with the act of reading, and built from a web of references to both consecrated literature and critically marginalized paraliterature. Clearly Mignola is a reader through and through. In particular, Hellboy owes a great deal to weird literature of the Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, Manly Wade Wellman, and Robert E. Howard variety. As Bukatman points out, weird tales often center on, or grow out of, acts of reading of esoteric and forbidden texts. Such reading can invoke monsters, or rend the curtain between our world and others. Hellboy, Bukatman realizes, partakes of this spirit of bibliomancy, this eldritch sense of reading as a passageway to the sacred and terrible. Weird fiction is a learned and antiquarian tradition, after all.

Further, Bukatman shows how, despite Hellboy’s penchant for rousing action, Mignola often makes the comics page a space of stillness and contemplation that briefly suspends the expected emphasis on profluence and momentum, instead calling attention to the very process of our reading. Bukatman argues that this “aesthetics of stasis and stillness” (in a comic about a big stomping red monster who kicks ass!) links to “a ruminative mode of reading.” That is, despite the headlong narrative rush of the stories, our reading is slowed and made self-conscious by modernist visual strategies. Though comics are typically “arranged to overdetermine the proper sequence of reading,” Mignola’s violate that expectation “all the time.” For Bukatman, the prototypical Hellboy page is “a contemplative space,” one in which readers are “encouraged to, not simply dwell, but glide around.” He observes:

What we find in Mignola, then, is an ostensible classicist […] who’s behaving a lot like a modernist. The treatment of page as page, the attention to surface, the de-emphasis on linear sequence, the move toward abstraction — all of this is less traditional than innovative.

In this way Bukatman not only opens Hellboy to various modernist comparisons, but also makes bold to declare that, ultimately, the book is “Hellboy’s natural habitat.”

[Hellboy 2] Hellboy takes the Fall — a page Bukatman reads in terms of color field painting (and Little Nemo). From Mike Mignola (story and art), Dave Stewart (colors), and Clem Robins (letters), Hellboy in Hell #1 (Dark Horse Comics, 2012). Hellboy copyright © and trademark of Mike Mignola.

The recently completed Hellboy in Hell revels in the bookish and meditative qualities that Bukatman favors. The first issue includes a sequence of puppet theater enacting Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, while the second gets Miltonic with its treatment of Pandemonium, capital of Hell, but also Shakespearean, echoing Macbeth. The series’s final issue, which appears to ring Mignola’s solo work on the character to a close, begins with an allusion to John Donne — the last chapter is dubbed “For Whom the Bell Tolls” — and is shot through with more Milton (and, I’d say, a touch of Melville too). Lovecraftian and Jack Kirby-esque touches are everywhere, of course. Visually, Hellboy in Hell climaxes with a dive into moments of almost pure abstraction, some of Mignola’s loosest, most gestural artwork to date. All this left me scratching my head, but I dug it, and read it again and again just to make sure that I wasn't missing out on cool things. It presents, in this respect, a very good example of Bukatman’s “adventure of reading.”

Hellboy’s World offers a loving, medium-specific study of comics, but is emphatically not a purist’s book. Even as the book explores qualities distinct to comics, it takes in a wide range of other cultural referents: to call it eclectic would be an understatement. Sculpture, film, abstract expressionist painting, illuminated manuscripts, children’s picture books — Bukatman draws on all these for the sake of comparison (and also on other comics that on first look differ sharply from Hellboy, such as art comics by Jerry Moriarty and Chris Ware). The book’s argument is wayward, zigzagging, and playfully syncretic, a trail wending through and joining diverse art forms and traditions. This is typical of Bukatman, whose books are marked by inspired acts of poaching from disparate fields and a knack for unexpected rhizomic links.

There’s a giddy joy to all this that should not be mistaken for frivolity, and that is very much Bukatman’s métier. His other most recent study, The Poetics of Slumberland (2012), is, in his own words, a very happy book, celebrating the ways that daydream and fantasy help loosen or provide partial escape from the strictures of modernity. In that book’s argument, modernism brings forth both new means of discipline and regimentation and new forms of resistance — that is, new spaces of play and ever-morphing “plasmatic possibility.” Slumberland looks at various examples of popular culture — from Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo, which inspires the book’s title and reigning metaphor, to My Fair Lady, the Van Gogh biopic Lust for Life, Jerry Lewis movies, and superhero comic books — and finds in their ecstatic fantasies a kind of momentary release or “fleeting refuge” from (perhaps even a playful mockery of) Taylorist demands for greater efficiency and conformism. It posits a “dialectic of regulation and resistance to regulation,” extolling disobedience, waywardness, illogic, and “little utopias of disorder” that resist, if only briefly, the straitened, schematized world of industrialized modernity. In short, The Poetics of Slumberland is a paean to pleasure. Hellboy’s World is an even happier book, in fact a downright cheerful one, exulting in the comics page as an aesthetic playspace. In that space, says Bukatman, reader and book are “entwined,” completing each other in a process he describes as something like a holy trance. Against the tide of popular and academic commentary that sees comics as “cinematic” — as little movies on paper — Bukatman embraces bookishness, silence, and the image of the spellbound reader who himself participates in casting the spell.

Some readers may miss the spirit of ideological critique that we’ve come to expect from academic criticism, a spirit more evident in Bukatman’s early books. Frankly, Hellboy’s World does not seem particularly urgent socially. Its author is neither the Bukatman who examined postmodern subjectivity through a cyberpunk lens in the magisterial, almost chilly Terminal Identity (1993), nor the cheekier though still serious Bukatman who critiqued hypermasculine superhero comics in the classic mid-’90s essay “X-Bodies: The Torment of the Mutant Superhero” (Matters of Gravity, 2003). A dream-vision of childhood reading as reverie informs all of Hellboy’s World — a vision inspired by a rhapsodic passage from Benjamin that addresses a reader “wholly given up to the soft drift of the text, which surround[s] you as secretly, densely, and unceasingly as snow.” Benjamin's child reader enters the text “with limitless trust,” drawn in, enticed, by its “peacefulness,” its absorbing silence:

His breath is part of the air of the events narrated, and all the participants breathe it. He mingles with the characters far more closely than grownups do. He is unspeakably touched […] and, when he gets up, he is covered over and over by the snow of his reading.

Bukatman quotes this passage on his first page, and appropriately so. From Benjamin’s bookishness, Hellboy’s World derives a model of comics reading that is all about contemplation, not the passive reception of spectacle. If The Poetics of Slumberland envisions fleeting escapes from regimentation, Hellboy’s World luxuriates in reading-as-doing and reading-as-refuge.

Both Benjamin and Bukatman envision the child reader as one who reads alone, a free and autonomous explorer of books and storyworlds. That would be a privileged child. This view of reading is not cooperative or collaborative. For all of Bukatman’s attention to picture books, he doesn’t seem interested in the shared reading experience of child and caregiver which typifies that genre — what scholar Joe Sutliff Sanders has called the picture book’s “prototypical” reading scene. Instead Bukatman thinks of reading as independent discovery. What he’s writing about, in essence, is solitary aesthetic pleasure, and a kind of connoisseurship.

This jibes with a backward-looking trend in Bukatman’s recent work, away from the daunting postmodern futures he addressed in Terminal Identity and his 1997 book on Blade Runner. His more recent work moves from the early to mid-20th century modernist scenarios that inform The Poetics of Slumberland into the frankly antique weirdness of the Hellboy mythos, which Bukatman sees as defined by book-love and which gives him a way to celebrate the autonomous “adventure” of reading. Much of Hellboy’s World consists of reveling in past art — Rodin, expressionist paintings, the films of Yasujirō Ozu — and demonstrating its relevance to a decidedly antiquarian comic. (Here we might note how many of Mignola’s projects, such as Witchfinder, Baltimore, Lobster Johnson, Joe Golem, and much of the B.P.R.D. canon, are period pieces.)

This is not to diminish the scope of what Bukatman has accomplished in this newest book. Hellboy’s World is written with such joyfulness and panache that I find it a pleasure to page through, again and again. Beautifully designed, bountifully illustrated — all scholarly tomes on comic art should look this good — the book itself partakes of the Mignola Effect. To pop it open anywhere and read Bukatman’s prose alongside Mignola’s images is to invite distraction. But there’s more: Bukatman envisions, and models, a way forward for comics studies itself, as a perhaps marginal, certainly impure field straddling various disciplinary fault lines within academia. He draws from scholar and experimental writer-performer Allen Weiss a thesis about “monsters” that could stand as a fair description both of the status of comics and of his own eclectic method. “Monsters,” Weiss writes, “exist in margins. They are thus avatars of chance, impurity, heterodoxy; abomination, mutation, metamorphosis; prodigy, mystery, marvel.” This maxim serves Bukatman as an epigraph. The words impurity and heterodoxy aptly describe the genre-splicing, synthetic bookscape of Hellboy; the curious, roving critical practice of Bukatman himself; and the possibilities for comics studies as a field in the margins, on the edges, but alive with possibility. Quoting from Michael Camille’s classic Image on the Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art, Bukatman adopts the word “monstrous” to describe his own method of studying marginalized objects, such as comics, that “elude or slip through the network of classifications that normally locate states and positions in cultural space.” (In fact that phrase comes from Victor Turner’s classic anthropological work on liminality, quoted by Camille.) Comics studies, as a field, partakes of this same monstrousness, this interstitiality. Hellboy’s World embraces that status more wholeheartedly than most monographs in the field. With its gleeful embrace of the heterodox, the weird, and the liminal, this little book could mean big things to comics studies, going forward.

In other words, I cannot help but read Hellboy’s World as a challenge to the comics studies field — my field — or more precisely to certain academic habits that threaten to blind or box in the field. There is now a respectable segment of the comics world devoted to graphic memoir, documentary comics, political witness, and to a lesser extent realist literary fiction — a rich vein of work that has inspired a bookshelf’s worth of scholarship, much of it likewise rich and compelling. Its achievements are the delayed harvest of the alternative comics of the 1980s and ’90s — a fruitful era that continues to inspire. But Bukatman reminds us that the comics world stretches well beyond that respectable neighborhood, that commercial or so-called genre comics hold their own fascinations, that they too invite and reward aesthetic study, and that the currently teachable canon of comics as serious Literature and Art risks hiving off a big chunk of what is exciting about the form. Hellboy’s World offers a model of what a less anxious, less status-conscious, and freer practice of comics studies could be. It’s also as good an example as I’ve seen of what it means to write criticism of popular art from a place of joy, of exultation. It is a marvel, a very happy monster, indeed.

¤

LARB Contributor

Charles Hatfield is professor of English at California State University, Northridge, where he teaches courses on comics, word and image studies, popular culture, children’s literature, science fiction, and fantasy. He is the author of Hand of Fire: The Comics Art of Jack Kirby (University Press of Mississippi, 2011) and Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature (University Press of Mississippi, 2005). He is also president of the Comics Studies Society.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Comic Book Melancholia

Jason Middleton looks at the most tragic death in Marvel Comics.

Before “Biff! Pow! Bam!”

What we need is a comprehensive examination of the history of popular literature with a view toward cataloging what we might call "proto-superheroes."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!