A Fight for Survival: On Somaiya Daud’s “Court of Lions”

Iman Sultan reviews Somaiya Daud’s “Court of Lions.”

By Iman SultanDecember 26, 2021

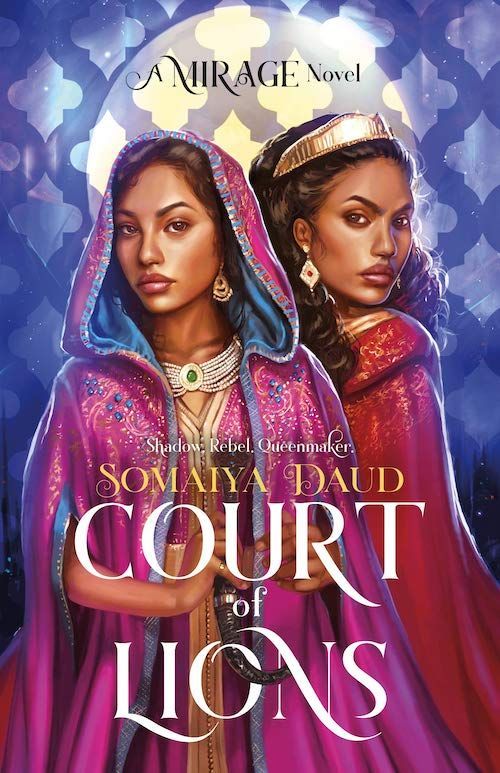

Court of Lions by Somaiya Daud. Flatiron Books. 320 pages.

COURT OF LIONS, the second installment in Somaiya Daud’s sci-fi duology, continues the journey of Amani, a farmer’s daughter, who is kidnapped from her home on a pastoral moon and forced to become the body double of the tyrannical princess, Maram, the mixed-race heir of the colonial Vathek empire. Amani, who is 16 when she enters the imperial court as a slave with a possibly fatal political purpose, is not content with her fate, and secretly joins the rebels plotting to dethrone Mathis, Maram’s father, even as an unlikely friendship blossoms between her and the princess. After an assassination attempt on Maram from the rebels, Amani, who voluntarily takes Maram’s place, also intervenes to save the 14-year-old assassin from instant execution. She is tortured and imprisoned as a result, risking her survival in the serpentine “Ziyaana,” or palace.

While taking place in an imaginary intergalactic universe, filled with stars, spaceships, and a brutal, technologically advanced monarchy, much of Daud’s epic series is inspired by real-world themes and events, namely colonial occupation, and the racial dehumanization and authoritarian rule which allow it to perpetuate. Andala, the planet on which Amani and Maram live, is “the result of the thought experiment [of] ‘what would Morocco in space look like,’” Daud says, and has been colonized by the Vath, a silver-haired people who can no longer live in their own planetary system because they’ve poisoned it. Similar to most dystopian sci-fi books and films preceding it (Star Wars, The Hunger Games, Divergent, Avatar, etc.), the Mirage series explores the darkness and extreme vicissitudes of what’s possible if climate change, resource extraction, and interplanetary conquest prevail at the expense of shared humanity and universal values.

And yet, what sets Daud’s series apart from its forebears is the richness of her world-building of Andala, which is steeped in North African folklore, Arabic poetry, and the historical court life, nobility, and pastoral or tribal culture of the medieval Maghreb. Rather than simply diversifying sci-fi, a genre that has often been the terrain of white men, Daud succeeds in building a multifaceted, original world that has culture and depth, even as it faces existential threat by the Vathek empire.

Court of Lions thus continues where Mirage left off, following Amani’s survival in the Ziyaana, her sacrifices to protect her family, and her star-crossed romance with Idris, Maram’s fiancé. If the first novel focused on Amani’s thrilling transformation from a body double to a secret agent, working alone inside the system for the anticolonial rebellion, Court of Lions traces these threads as they converge into a sophisticated and intricate tapestry of court intrigues, military alliances, and political lobbying of Andalaan nobles to join the rebellion, overthrow the empire, and build a new world. The first, and most complex, target to achieve for Amani is the future queen herself, Maram.

Despite their uncanny physical resemblance, Amani and Maram are polar opposites, separated by class, culture, and political allegiance. Amani has grown up in poverty with a loving family and reads devotional poetry to the prophetess Massinia, banned by the Vath as a symbol of dissidence. In contrast, Maram is the loathed “half-breed” child of the deceased Queen Najat, who was forced to marry Mathis in a coercive alliance, and died before she could raise her daughter. Maram looks Andalaan and is disliked by the Vath, and has been taught to disdain her mother’s family and people, navigating the unenviable tightrope of facing rejection from both worlds, but tasked to eventually rule over both of them.

Amani understands Maram’s confusion and vulnerability, and she unhesitatingly adopts the role of queenmaker. “I knew that if given the chance, she would be a great queen. […] There existed in her a woman who could lead our planet to prosperity, who cared about justice — she only needed to be coaxed out,” Amani reflects as she guides the future queen. The novel is then interspersed with episodic chapters in the past from Maram’s point of view, where the princess visits a seaside estate and reconnects with the memory of her mother. A mysterious falconer, Aghraas, appears and helps change the course of Maram’s decisions, her personal introspection, and the fate of the galaxy.

While the nonlinear storytelling exposes us to Maram’s interior state and is quietly, resonantly written, it disrupts the pace and drama of the main narrative from Amani’s perspective. The fact that Maram’s introspection occurs in the past makes it difficult to link her characterization and decisions in the present, and the blank spaces in the narrative come at the expense of the believability of the larger plot; Maram’s motivations are left to the imagination. Daud fails to weave Maram’s chapters effortlessly in the rest of her novel, resulting in choppy, unsatisfying writing. Unfortunately, the poor execution affects how the entire story and its outcome unfurl.

Meanwhile, Amani continues her machinations in the rebellion. Being the body double of the princess thrusts her in the unique position of knowing and meeting the Makhzen, the Andalaan nobility who have no love for the Vath, but are powerless to resist. Much of Amani’s interactions with the Makhzen are natural and friendly, forming a communal bond on the basis of ethnic kinship and oppression. She doesn’t reveal her true identity to any of the indigenous nobles, other than Rabi’a, a dignified noblewoman who is also a collaborator with the Vathek regime, part of the only family left standing after the Purge that killed most of the Andalaan nobility.

Amani’s negotiation with Rabi’a to join the rebellion reveals another lapse in Daud’s storytelling. Colonialism was largely successful in human history due to the collusion of landowners, administrators, and intellectuals with the foreign aggressor to exploit the larger, poorer population. Even within the logic of alternate galaxies, the underlying assumption that all of the Makhzen would unite under the banner of rebellion is extremely skeptical at best. The deprivation and fight for survival would, if believable, render at least one or few of the indigenous nobles as manipulative, complicated, or duplicitous — by necessity, if nothing else. But nearly all of the Makhzen are portrayed as sincere, honest, innocent, and morally upright. The sudden idealism of Amani’s cause undercuts the grim and pragmatic political reality that has shaped most of the story up until now.

Amani’s relationship with Idris, the sole survivor of his family from the Purge and Maram’s fiancé of political obligation, is more nuanced and layered. Because of the immense cost his family faced for rising up against Vathek rule, Idris opposes rebellion of any kind, preferring survival under tyranny to liberation from it. When Idris discovers Amani’s subversive activities, the lovers’ world shatters, and Amani abandons Idris because he expects her to accept her dehumanized condition as a slave. Daud explores the age-old dichotomy of surviving versus living through the hero and heroine, and sparks an incisive political dialogue on the choices one makes when facing oppression.

In the seminal anticolonial text The Wretched of the Earth, Frantz Fanon writes of the black-and-white world of the colonized and the colonizer, a world that is “compartmentalized” and “divided in two.” Decolonization, as a result, “is always a violent event. […] [I]t cannot be accomplished by the wave of a magic wand, a natural cataclysm, or a gentleman’s agreement. […] [It] is an historical process.” To put it simply, the resistance movement that rises to overthrow the colonial regime shapes the contours of decolonization and the reclamation of the subjugated people and culture, the nurturing of a new world and identity, transforming everybody in the process. Court of Lions has internalized the Fanonian ethos of a world divided in two, and the necessity of violent rebellion, but it arrives at its victorious conclusion in an extremely anticlimactic fashion. Court maneuverings trump decolonization as a movement that transforms the indigenous people, and Maram’s own introspection and romantic relationship with Aghraas, a mystical figure, becomes a weak substitute for the public ties the princess would have been forced to build with her people to become their queen. The plot and the larger message of the book are lost to the individual whims and feelings of the elite characters, when what made Mirage so powerful and refreshing was how the heroines navigated living in a world where they were treated as collectively inferior, despite coming from opposite ends of the status quo.

And yet, in the series finale, the growth and transformation that accompany any earth-shattering event like regime change, decolonial liberation, or even the protagonist winning the war are conspicuously missing. The scene of victory over the Vath and the assassination of Mathis are too quick and easy; barely any blood is spilled. Too little is sacrificed to make the final victory convincing, and the reader is left feeling that they were promised a revolutionary and dramatic epic, but have arrived instead at a diplomatic discussion in the drawing room.

Perhaps this is indeed Daud’s point; wars can be won with words or a battle of the wills, but it’s still at contrast with the setup presented in Mirage and the beginning of Court of Lions. As a series finale, the novel’s ending is unsatisfying, but it nevertheless leaves things in medias res to give way for future novels or spin-offs. Amani and Maram’s journey is far from over, and the new world they will build together is heralded as just the beginning.

¤

LARB Contributor

Iman Sultan is a journalist covering politics and culture. She enjoys young adult fiction, badass heroines, and stories of suspense and adventure. She tweets @karachiiite.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Many Worlds in Between: A Conversation with Kenan Trebinčević and Susan Shapiro

Puloma Mukherjee talks to Kenan Trebinčević and Susan Shapiro about their new middle-grade book, "World in Between: Based on a True Refugee Story."

Fanon Can’t Save You Now

Todd Cronan looks at “The Political Writings from Alienation and Freedom” by Frantz Fanon, edited by Jean Khalfa and Robert J. C. Young.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!