A Feminist Chorus: On Clara Schulmann’s “Chicanes”

Edmée Lepercq reviews French author Clara Schulmann’s newly translated book-length essay “Chicanes."

By Edmée LepercqDecember 15, 2023

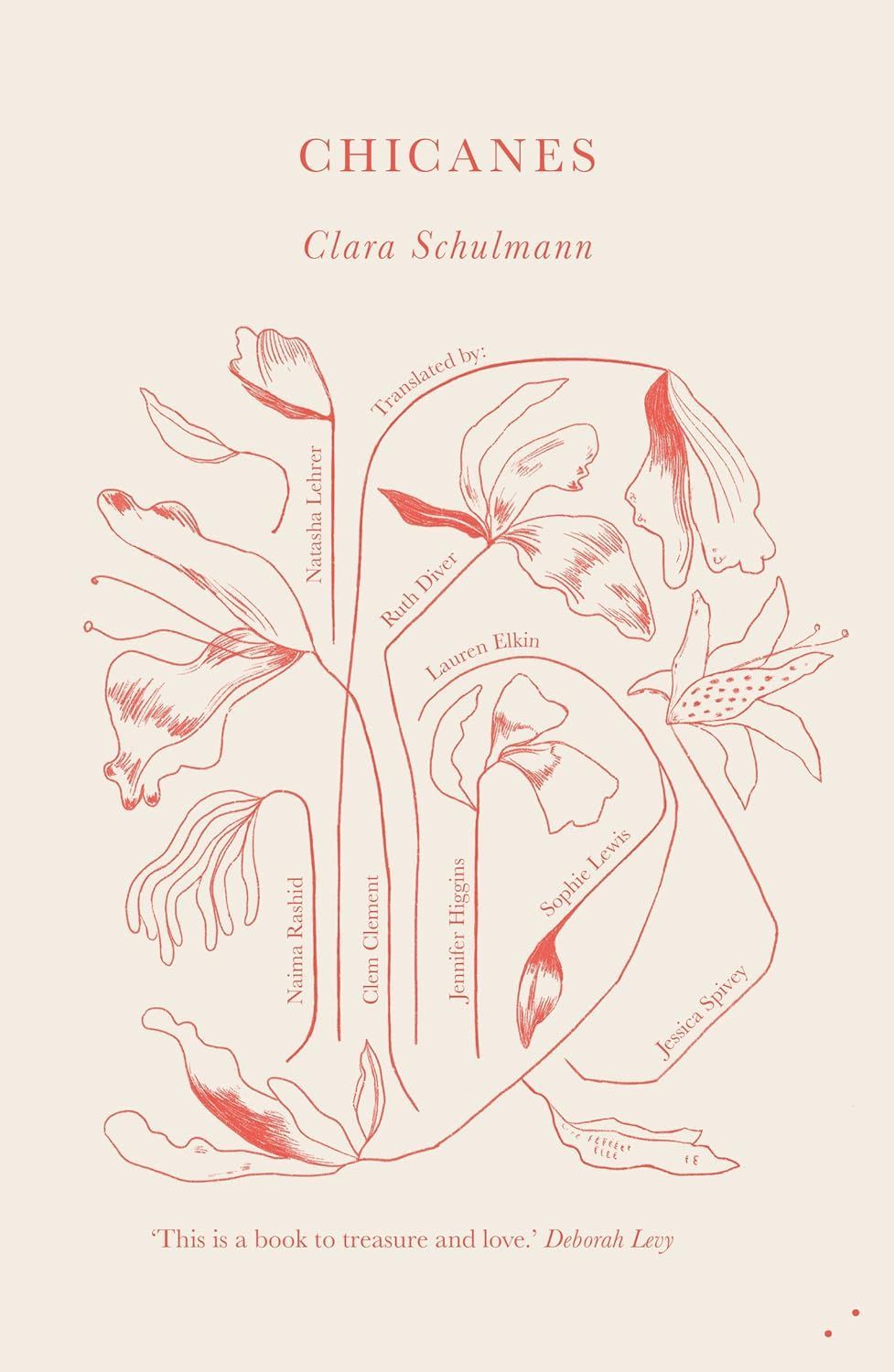

Chicanes by Clara Schulmann. Les Fugitives. 210 pages.

WOMEN’S VOICES have been a metaphor for female agency since the suffragette movement, if not since “The Little Mermaid.” To break the silence, to find your voice, to speak up and make yourself heard—no other metaphor captures so well the connections between the body and the intellect, the individual and the collective, the private and the public. “Voices create a circuitry between our inner and outer selves, and that’s why they are fragile,” a friend tells Clara Schulmann at the beginning of her book-length essay on women’s voices, Chicanes (2023). Schulmann says this entanglement is sometimes hard to unravel, but the challenge forms the gist of what she is trying to accomplish through her polyvocal book.

Originally published in French in 2020, Chicanes opens with Schulmann seeking comfort and guidance in the voices of other women. She has just lost her teaching job, and her partner is gone. “Up to this point,” she writes, “I had been navigating my way somewhat aimlessly through feminist readings, paying attention to the way one describes one’s life, the way one narrates it; these elements are suddenly brought sharply into focus.” She begins by researching women’s voiceovers in Hollywood film, but this somewhat academic project expands to include the voices of women she hears in everyday life. She reads and listens to journalists, fictional characters, friends, academics, writers, students, and even the angry voicemail a letting agent left on her friend’s phone, paying close attention to the ways they think out loud.

The book is divided into chapters that explore specific qualities attached to women’s voices, such as “overflowing,” “irritation,” or “fatigue.” Each chapter is composed of fragments—personal anecdotes from Schulmann’s life, critical analyses, extracts from interviews or books. Almost every page either quotes a woman or describes her and her work. Few names repeat. Some are internationally famous, like Hillary Clinton, bell hooks, Charlotte Brontë, and Jane Fonda, but most are refreshingly not. There’s Nina Donovan, a 19-year-old sociology student in Tennessee who recorded a spoken-word poem denouncing Trump’s America, and Mhairi Black, the youngest person elected to the Scottish Parliament. Isolated from their original eras, contexts, and disciplines, these women’s voices are collaged together in Schulmann’s text to create a new community. The publisher of the English version, Les Fugitives, also had the excellent idea of hiring not one but eight translators, one for each chapter: Naima Rashid, Natasha Lehrer, Lauren Elkin, Ruth Diver, Jessica Spivey, Jennifer Higgins, Clem Clement, and Sophie Lewis thus add their voices to Schulmann’s original chorus.

Schulmann argues that feminist voices are most often associated with manifestos and speeches. In Chicanes, she aims to focus on voices that embody a different quality. She pays attention to silences, hesitations, whispers, and murmurs, to voices that are too lyrical and too emotional, voices that are acerbic and raspy. She highlights the fact that the French word for emotion contains roots to words such as “move,” “motive,” and “mutiny.” She aligns her text with a feminist tradition that embraces the weakening of the body and the political charge of the emotive. While the book can range far and wide, Schulmann’s interest always remains the disruptive quality of voices, the way they can break established values, even when speaking haltingly or quietly.

In Chicanes, each translator has their own way of voicing Schulmann’s original French text. I was most aware of their individual voices in the first pages of each new chapter, where subtle differences in rhythm, vocabulary, register, and tone were most strongly felt, if not easily identifiable. After a few pages, my awareness of the translator’s voice faded, and I tuned in once again to Schulmann’s own. There is, however, a fragment in which Schulmann discusses the idea of translation as something that exhausts language in the same way that plagiarism or clichés do. She cites an essay by literature professor Emily Apter on the translation of Madame Bovary by Eleanor Marx (Karl’s youngest daughter). Marx defends translation that seeks to be as close to the original as possible, and Apter views this as championing the translated text as “de-authored, neutered, de-owned.” I’m not sure if Schulmann would relate this to her own translated text. I think the multiplicity of translators involved highlights instead how the translator’s voice in a good translation coexists beside the author’s, neither neutralizing the other. Still, there is no denying that translation can serve to muffle the original text. Writer and translator Lauren Elkin (who worked on Chicanes) once evoked this very problem when she said that she no longer recognized one of her own texts after a bad translation—as though the translator had spoken too loudly over her own voice.

Schulmann’s own voice is warm and personable, even in the more academic passages that give hints of her work as an art critic and teacher. You get the sense of her drawing you into her circle of smart female friends and co-workers. Her approach is horizontal rather than vertical: she engages with her material through personal connection rather than a position of authority. The strongest voices in the rest of her female chorus are those shaped for public speaking, such as academics, writers, artists, and politicians. Schulmann openly regrets not having included more everyday voices in the book, a feeling I sometimes shared. She writes of her casual catch-ups with friends:

Several times I’ve put the phone down and regretted not having recorded all these conversations. They are the most fully developed image of lives shot through with annoyance, irritation and disappointments, and they manage to turn things around with humour, rejecting the seemingly inevitable. I often have the sense that these female characters, who are very real and all around me, are true heroines, champions of organization as much as of chaos, and that their ability to articulate and join up these scattered experiences has a literary quality.

The fragmented nature of Schulmann’s text, as well as her predilection for quotes, positions her book within a history of feminist literature that rejects traditional narrative strategies. Schulmann points to two influences on her methodology. The first is American poet Anne Waldman, who in the 1960s centered her writing practice on things she overheard during her daily life—on the radio, on the street, in the café. Schulmann quotes Waldman saying she was “completely charged by the constant activity—artistic, political—of the Lower East Side environment.” For Waldman, “[a]n immediacy and urgency took hold to write all waking and sleeping details down quickly—as witness, as eyeballer of phenomena—and accept whatever shape they took.” Like Waldman, Schulmann sketches a portrait of an intellectual environment through her specific viewpoint, without necessarily lapsing into the merely personal. Through the accumulation of voices, she highlights how any woman is shaped by the creative and political efforts of those who came before her, as well as their frustrations and uncertainties.

The second influence Schulmann points to is an event she organized: a reading of the texts of Laura Mulvey, the theorist who famously coined the term “male gaze,” entitled “A Feminist Chorus.” After recruiting a variety of people to read, sometimes over one another, she emphasized that a central element to the performance was its unrehearsed quality: the performance was not about individual voices, but the feminine and feminist sound they created together, even or especially when they overlapped. “Cacophony is a technique in and of itself, which defies the expectation of readability,” Schulmann writes. “The meaning of the words disappears, but the sight of all these women standing, mixing their voices in the dark, their faces flickering in the cinema, evokes an emotion that only improvisation and rapidity can provide.” Sometimes the chorus of Chicanes dips into the cacophonous, and we are left with the sight of all these women, some famous, some less so, mixing their voices, giving form to what might otherwise be difficult to communicate. Listen in.

LARB Contributor

Edmée Lepercq is a writer based in London.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Voice of Feminism: On “F Letter: New Russian Feminist Poetry”

Francesca Ebel listens to the varied voices of “F Letter: New Russian Feminist Poetry.”

The Free Labor Force of Wives: A Conversation with French Feminist Writer Christine Delphy

Annie Hylton talks to French feminist Christine Delphy about domestic labor and #MeToo.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!