A Down-and-Out but Amusing Character: On Alex Harvey’s “Song Noir”

Dec Ryan reviews Alex Harvey’s “Song Noir: Tom Waits and the Spirit of Los Angeles.”

By Declan RyanDecember 9, 2022

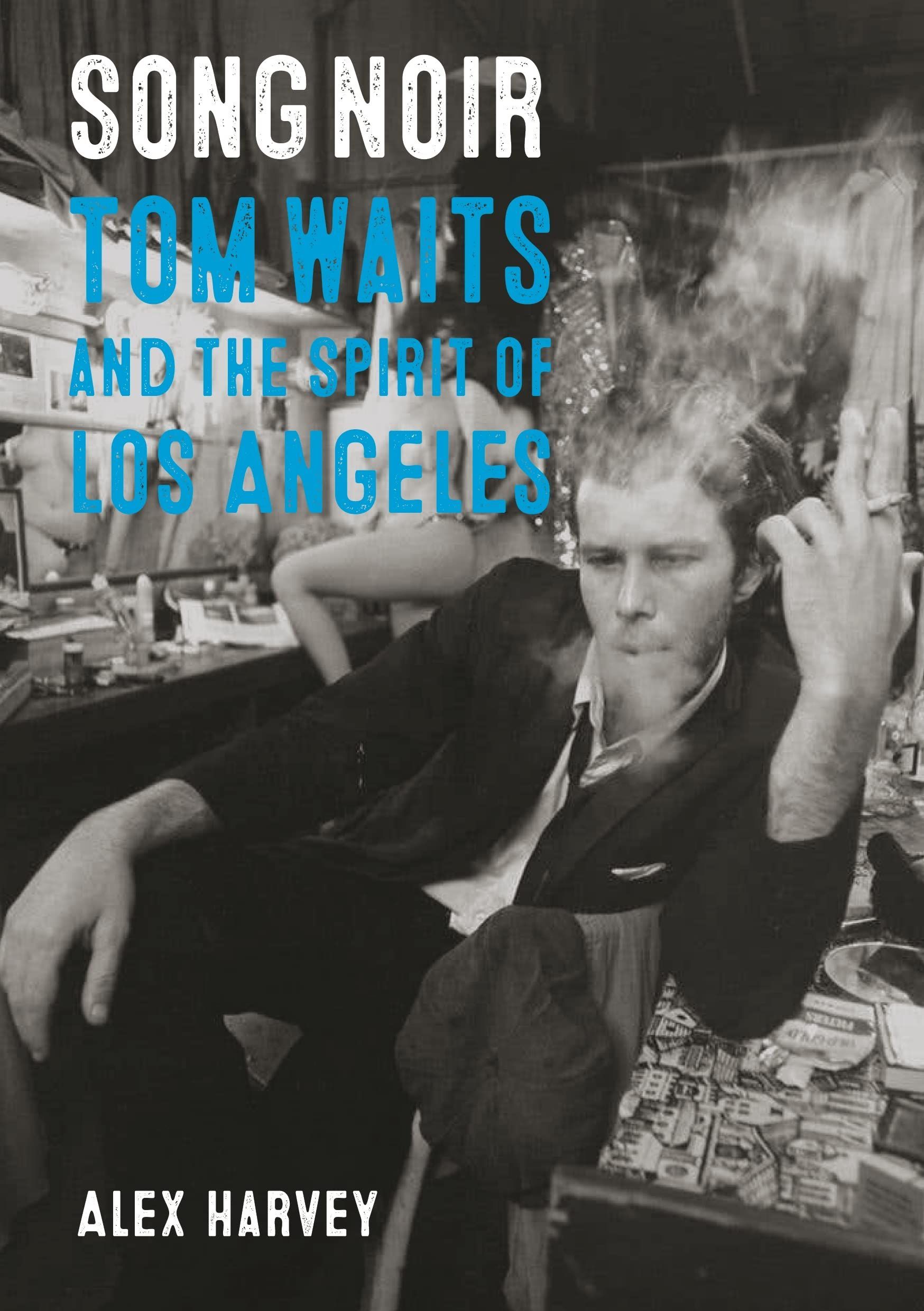

Song Noir: Tom Waits and the Spirit of Los Angeles by Alex Harvey. Reaktion Books. 240 pages.

TOM WAITS WAS conceived at the Crossroads Motel in California, “amidst the broken bottles of Four Roses [and] the smoldering Lucky Strike,” and was also born “in the back seat of a yellow cab.” Or at least “Tom Waits” was, and, as Alex Harvey’s new book Song Noir: Tom Waits and the Spirit of Los Angeles shows, for the first few years and several records of his career, Waits so inhabited his role as a kind of throwback barfly and jazz-infused vaudevillian that it would take a fairly stony-hearted literalist to worry about such trifling matters as facts. A case study for printing the legend, Waits, as Harvey adeptly shows, immersed himself in disparate influences — literary, musical and somewhere in-between — in part as a search for replacement father figures and in part to take his method approach to being an L.A. deadbeat, a nighthawk and curb raconteur, and turn it into late-night melodies.

Harvey is sensitive to the delicacy of doing too much unpicking when it comes to the fairy tales, but he does supply insights and levelheadedness where it’s useful to the narrative, or to illustrating the work, to do so. The snatches of Waits’s early family life — growing up in Whittier, California, in the 1950s, before his mother took the children to San Diego County in 1960 following her split from their father — are especially interesting: his trademark growl “was acquired by imitating Uncle Vernon’s rasping voice, which had been caused by a throat operation. Doctors forgot to remove the scissors and surgical gauze”; his father Frank, an alcoholic who would cast a long shadow over Waits’s writing, “played in a mariachi band at night” and later burned down the family home. When these are the true parts, it’s no wonder Waits took to letting invention have the floor.

Waits learned guitar from a high school dropout who “lived […] in a trailer by a mud lake with tyres sticking out of it,” while the roots of his garrulous, storytelling bar persona were, at least in part, planted during his teenage years of playacting an old man: “Wore my grandaddy’s hat, used his cane and lowered my voice. I was dying to be old.” Waits would spend time with friends’ fathers, talking about “masculine subjects like lawn mowers and life insurance.” More formative than shooting the breeze about backyards, Waits would also listen to their jazz records, especially the albums of Frank Sinatra, an early and enduring musical passion and a clear touchstone not only for the sound of the early, loungier records but also for some of their artwork.

Harvey touches on the “almost too Freudian” image of Waits getting his father Frank’s old army Heathkit radio going again, “an object from which music would emanate,” but even after his abandonment of the family, Frank would still have a direct impact on the young Waits’s musical education. One of several “epiphanies” here occurs while driving with Frank to Tijuana, with Waits pointing to “hearing a ranchera on the car radio with my Dad” as something that changed how he viewed records, while those trips to Mexico — where music was embedded in the daily life, where “songs lived in the air” — would later influence the neighborhoods to which he was drawn in Los Angeles, as his own career began to take shape. Much of his other musical education came from older male figures who were equally out of kilter or keeping with the popular pulse: DJ Bob “Wolfman Jack” Smith, another growling figure, played soul and R & B records from south of the border, while the writing of the Beats, especially Jack Kerouac, fed into a predisposition towards the corners, the margins, the underdogs.

Kerouac’s writing, like so much rock and roll, was suggestive of escape, of the long drive and the open road, perpetual motion as a means of survival or purification. But while — as Harvey points out — the direct correlation between On the Road and a song like “Ol’ ’55” (on Waits’s 1973 debut album Closing Time), at least in their shared sensibility, was fairly clear, there was more nuance and complication when it came to Waits’s longer-term project than simply a need to hit the freeway or chase after some kind of new holiness. Instead, he was fascinated with, and drawn to, the misfits and outsiders, those who couldn’t escape — another literary influence, Charles Bukowski, was more in line with this aspect of Waits’s character, but Waits discovered the author, Harvey notes, after his debut record was released. Bukowski was then writing in Los Angeles Free Press, his stories of having “the pretense beaten out of you” adding to, rather than shaping, Waits’s outlook.

Waits had already been hanging out in some of the same dilapidated, unappealing haunts he’d find Bukowski writing about. Before catching his break, Waits had been an active listener when working at Napoleone’s Pizza House in National City, writing down the customers’ conversations, their “lustful” phrases tuning his ear and providing obvious inspiration for some of his spoken-word pieces, his syncopated stand-up act caught most fully on his third album, Nighthawks at the Diner (1975). Harvey is very good on the mixture of influences Waits was synthesizing in these early years — not only the well-known writers and big stars in his firmament such as Sinatra, Ray Charles, and Bob Dylan but also the film noir, the language of advertising and commerce, and another “epiphany” at a sleazy Sunset Strip club watching a Puerto Rican singer who “launched into a rambling, ‘psychotic confession — a cross between an execution and a striptease.’” As Harvey makes clear, Los Angeles itself was a character, a mythic and symbiotic backdrop against which Waits managed to remake himself into a persona while — paradoxically — looking for a means of maintaining some level of the authenticity he felt was missing in the Laurel Canyon brigade.

Authenticity for Waits didn’t translate to veracity, but some people — including the owner of the influential Troubadour club, where he first met his manager and began his ascent — didn’t buy Waits the deadbeat, Waits the skid-row tourist, failing to see beyond his middle-class Pomona upbringing into what was becoming the sort of mask that was increasingly hard to remove. Waits had sought anonymity of sorts, like a hardboiled detective in the throwback films that were now coloring his songwriting, wanting to live the life he wrote about, to inhabit or even create situations in order to be able to write about them with feeling. His flophouse lifestyle and curbside, cultish charisma may have drawn all manner of figures to him (mostly admiring, though not uniformly), but, as Harvey makes clear, there was increasingly nowhere to run to as the 1970s drew on, and Waits was typecast in a part he’d invented for himself. He’d also started to inhabit the role of drinker a little too enthusiastically, “a flask of whisky in his pocket at all times” when playing his part onstage, and becoming something of a downtime prop as well.

Harvey traces the roots of the early “Tom Waits” persona but is equally adept at showing Waits’s need to climb out of it, and the methods by which he did so. By Blue Valentine (1978), Waits felt artistically spent, telling a Troubadour regular that he was like “an old prizefighter who’s just going through the motions. I keep doing this character — the down-and-out but amusing and interesting Bowery character.” He was restless, becoming keen to put more effort and energy into his stage sets, “making a fiction in a nonfiction world,” the whole effect becoming more theatrical, more clearly a performance than an impression, or something reliant on that creaking, constructed persona. In another scene that might have come from his own back catalog, Waits was saved from his old act — variously — by Francis Ford Coppola and, later, his future wife Kathleen Brennan. While composing for Coppola’s 1982 film One from the Heart, an updating of classic Hollywood musicals, Waits met Brennan, who was working as a script editor, and the pair took to playing the — “almost too Freudian” — game of “let’s get lost” driving around Los Angeles, intent on seeing it all anew.

From the slow evolution of his records over the previous decade — tinkering with more or fewer jazz influences, allowing noir to infiltrate his narratives, or channeling Howlin’ Wolf and R & B’s immediacy by increments — Waits was about to perform a complete revolution in both his sound and his approach, with everything changing from the ground up. Spurred by Brennan’s encouragement, Waits would escape the confines of his labored-for persona, “hollow[ed] out” by alcohol and creatively punch-drunk, and retool everything from his label to his soundscapes. Uncoincidentally, as Harvey demonstrates, Waits’s rebirth came about when he felt willing to face down Frank’s abandonment of his family in a song, “Frank’s Wild Years,” but in a way that acknowledged the appeal of burning it all down to start over, however chaotic the impulse and traumatic the impact might be. He said, “In a sense I come from a family of runners. And if I had followed in my father’s footsteps I’d be a runner myself, and so would my kids.” Harvey describes Swordfishtrombones (1983), Waits’s last L.A. record and the last of his albums covered in the book, as a “parallel act of creative arson where he torches his LA base and past life”; once again, Waits’s finger is on the pulse of the city, in one final act of psychic unity. As with the increasingly violent street life of Los Angeles that had started to find its way into the noir murder ballads of Waits’s late 1970s records, so did his moment of purgative arson chime with the city’s history of burning months, its legacy of artistic and literal blazing.

Waits’s new songs were built from scratch, cutting ties to his earlier piano-led balladry or barroom tall tales and bringing influences from the odder corners of experimental music, figures like Harry Partch or Captain Beefheart now informing his backdrops, anything to hand being turned into a potential instrument. All this was in service of differentiating the figures at the heart of his new work, no longer just the familiar downcast drifters of Los Angeles but now global characters as well, scowling and barking over junkyard percussion. This dismantling of sonic habits came with an increased focus on performance, too: the songs were now really about their performance, almost short plays in themselves, pointing forward to the later influence of figures like Bertolt Brecht or Kurt Weill on his musical evolution. Waits had struck out for new territory, geographically and in every other way, but, as Harvey shows, it was an L.A. of the imagination, of legend, that he had to escape from every bit as much as the real streets, motels, and diners he’d haunted during that formative first decade of his career.

A little hamstrung by not being able to quote directly from Waits’s lyrics, Harvey nonetheless has done a fine, impassioned job of piecing together the bricolage from which this most elusive, self-mythologizing figure set about assembling that “down-and-out but amusing […] character” who happened to write some of the most interesting songs of his era, but who in the end had to be burned away by the man behind the mask, for whom restlessness, self-invention, and an open road had always been at the heart of it all.

¤

Declan Ryan’s first collection, Crisis Actor, will be published by Faber & Faber in 2023.

LARB Contributor

Declan Ryan’s first collection, Crisis Actor, will be published by Faber & Faber in 2023.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Charles Bukowski’s Lush Life: “Post Office” and the Utopian Impulse

Half a century after publication, Bukowski’s novel remains a protean depiction of Los Angeles’s beauty and squalor.

Tangled Up in Blue Poetics: Timothy Hampton Reads a Bob Dylan for the Ages

Rob Wilson considers “Bob Dylan’s Poetics: How the Songs Work” by Timothy Hampton

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!