A Diary Is a Place for Dreaming: A Conversation with Amina Cain

Natalie Dunn speaks with Amina Cain about her new book “A Horse at Night: On Writing.”

By Natalie DunnDecember 30, 2022

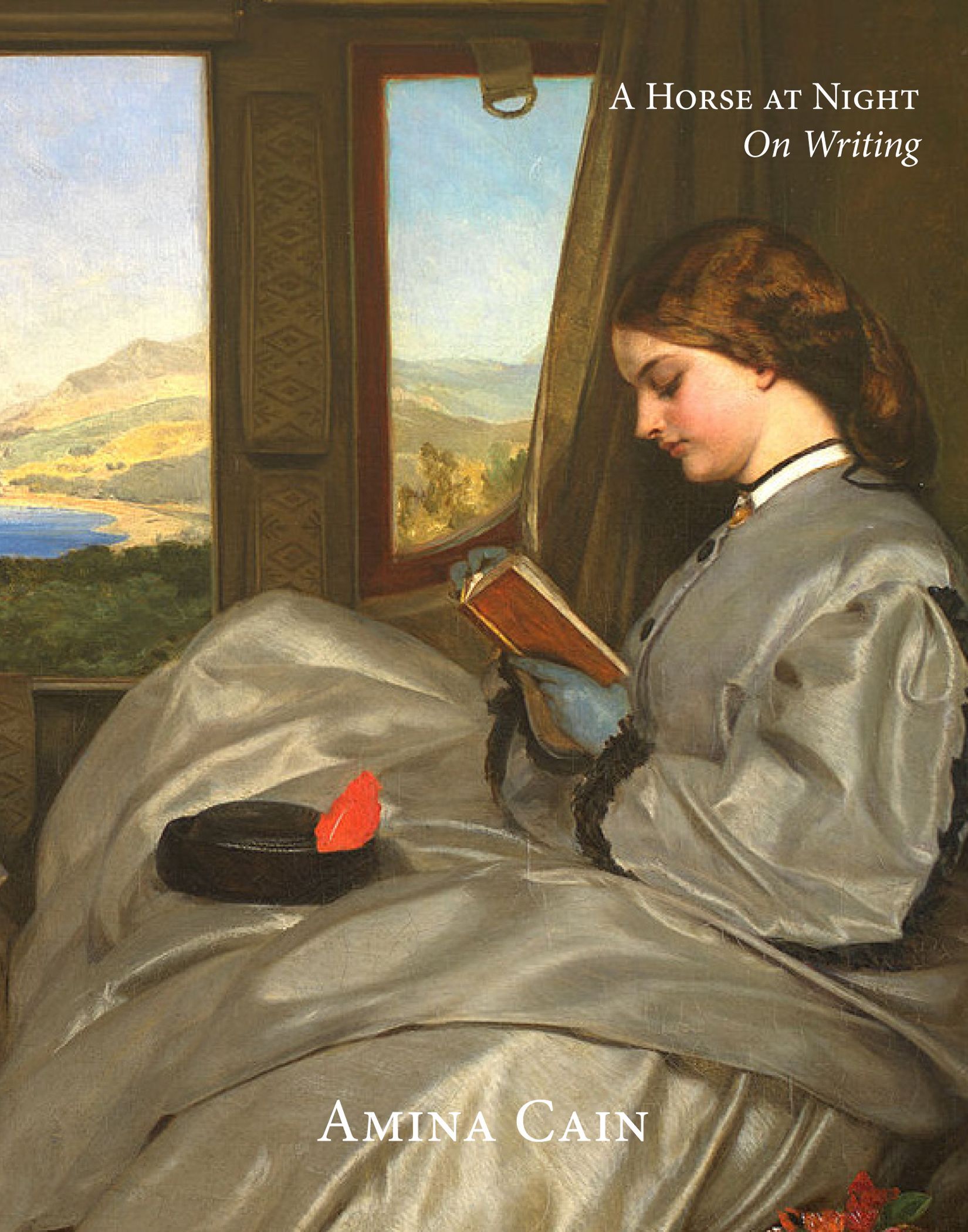

A Horse at Night: On Writing by Amina Cain. Dorothy Project. 136 pages.

WHEN I FINISHED A Horse at Night: On Writing, Amina Cain’s newest book, which describes itself as a “diary of fiction,” it was the middle of the afternoon. I was sitting in a café across from a friend, much like (and unlike) The Travelling Companions, Augustus Leopold Egg’s 1862 painting featured on the cover of the book. Cain writes in a passage on friendship: “What does it mean to be close, or to be distant?” I wondered what my friend across the table was thinking in that moment, wanting all of the distance between us to disappear.

This is often the feeling I have after reading Cain’s work: a desire to be close to the world and people around me. Much like Cain’s debut novel Indelicacy (2020), A Horse at Night illustrates, with gentle accuracy, a life both inextricable from and transformed by writing and reading. Cain writes, “One reads or writes a novel like one goes out to walk in the heat, or into the rain, to buy the persimmon and the butter.”

A Horse at Night is an intimate record of what it means to be a reader, a writer, a friend. In her first nonfiction work, Cain explores the contours of pleasure and boredom, freedom and landscape in fiction and in daily life.

¤

NATALIE DUNN: A Horse at Night begins, “Without planning it, I wrote a diary of sorts. Lightly. A diary of fiction. Or is that not what this is?” I wanted to ask first how A Horse at Night came about, how this book began.

AMINA CAIN: In many ways, the book came to me via my publisher. I’m a fiction writer who is always thinking about the possibilities of the form, and Danielle Dutton and Martin Riker at Dorothy have helped me, through the books they publish and as editors, go further in this thinking, both in the stories and novel I’ve written, and in my writing about fiction. I wanted to write a book about fiction for them. Though A Horse at Night isn’t perhaps a real diary, it became a diary-like space where I could think through my reading and my writing. And though the book began as individual pieces, it eventually became clear that when I wrote these pieces, I was returning to something, that they were more of one piece than I had first imagined. A diary is a kind of return, a place for dreaming.

You mention all of your unfinished diaries at the beginning of A Horse at Night and how so many of them begin with a single sentence or passage, only to be followed by blank pages. You write, “I don’t know if, when I wrote essays, I was actually returning to the same space, if somehow I had managed to get back to those empty pages, managed to get back to a pasture of thought.” I love the idea that the blank pages in one’s diary might actually be leaving room for something new to be created. It’s a beautiful way to see them.

For me, blank pages hold value because of their very emptiness, because they give some space to what I do write. I am forever drawn to, and trying to find, space. Those diaries filled with space are like quiet launching pads, and they’re peaceful because they don’t hold any pressure. When I write in a diary, I’m not trying to do anything, just reflecting on some aspect of my life or writing. It puts me at ease. The entries perhaps help me to stay at ease when I move into a different writing space, like an essay or a novel. They cast their spell.

In A Horse at Night, you write of how sentences can serve as a kind of haunting, “conjur[ing] something that isn’t there, so that it both is and isn’t appearing.” This is a fascinating concept, and I wonder if you could talk more about haunted sentences and the experience of both writing and reading them?

I have a great love for sentences, for what they are capable of, and at a certain point I realized that, in some respects, I write fiction simply to dwell in the space of them, and to create imagery, too. When you come at a work of short fiction or a novel from this direction, I think it changes what your sentences are like, what they are made up of, and what they are doing. For me, they are less a vehicle for telling a story than a space in which anything might happen, including a kind of haunting. That I might be able to inhabit my sentences not just as a storyteller, but in a more mysterious or loaded way, is exciting to me, as is the idea that narrative might unfold from this kind of space. And when I’m reading, I’m prone to being just as swept away, sometimes even more so, by a writer’s sentences as I am the subject matter. This to me feels spectral. Sentences hold an uncanny power. I don’t think I’ve ever thought that of plot.

I am also prone to being swept away by writers’ sentences — so much so that I find I can forget where I am in a story. It is interesting to think that this kind of attention to the sentences themselves can reveal another layer of the narrative. There are so many sentences in your work that have transported me somewhere.

A Horse at Night feels like a haunted title, maybe because it conjures up an image and feeling beyond the words themselves. You write how coming up with a title can be harder than composing a sentence. I’m curious how you settled on A Horse at Night as your title for this book?

To be honest, I agonized over it. I’m amazed at how long I can work on a book without it presenting to me any real title. This was true for my novel Indelicacy (which my husband Amar basically titled for me), for A Horse at Night, and now for the novel I’ve been working on for the last two years. I try everything: I try to not think of a title to see if my unconscious mind will find it; I reread the manuscript to see if anything will jump out; I write down my favorite words. I’m so jealous of writers who begin a book already knowing, who are good at titles. In the end, with this book, I wanted a title that hinted at an image without overdetermining it, that was a little mysterious, only partly able to be seen. Plus, the horse began to appear in the book, so it felt right that it appeared in the title too. I like that an animal is there. Even though the book is so much about writing, I knew I didn’t want the title to have anything to do with craft.

I’m interested in the way you write about boredom. In A Horse at Night, you write, “I sometimes get bored of myself,” and in Indelicacy, you write, “Writing was not the only thing I wanted to do, but the [most] important thing […] I’d look at my notebook and feel bored. After some time, however, it was my life that was boring, and I missed writing, so I would begin to write again.” Where does your interest in this topic come from, and what is the relationship between boredom and writing for you?

Well, writing is boring sometimes, and so is life, and sometimes, so is the mind. Luckily, most of the time, I’m not bored, and as a person and a writer, I’m interested in heightened states and experiences, but as part of that spectrum, I’m interested in boredom, too. When I’m bored, it usually means I’m restless, that I want something to happen — something extraordinary — but it isn’t happening. In those moments, I’m looking for an escape from the mundane, even though I am often drawn to, and write about, the mundane.

When I’m bored, it probably also means that I’m not truly being present with what is, attuned to the current state of things or to where I am. It also means that I’m being impatient, that I want things to happen more quickly than they are. I’m a slow writer, and though I accept that, and believe that my voice and style come out of that slowness, sometimes I’m bored by it. I’m bored by bad writing, but I don’t always know how to get to what feels good without first mucking through the bad.

In a way, I like the space of boredom because it’s part of where desire comes from. It’s human. And there’s a difference for me between a “productive” boredom versus a boredom that feels unbearable, like a stop or a wall. For instance, even though I find parts of Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles to be boring, I also find it incredibly profound. It’s one of my favorite movies. Sometimes I find aspects of Clarice Lispector’s fiction boring, but she’s one of my favorite writers. It’s hard to explain. Anytime I’ve done a daylong meditation retreat, I’ve gotten excruciatingly bored, but the thing is, I can’t get to the “depths” (if there is such a thing) without the boredom. I feel that one must be okay with boredom, and know that there can be value in it, that it can transport you. Sometimes one must be able to sit with something for a long while.

I love thinking about boredom in this way — something inevitable and important, a space that represents tension, a space desire stems from.

In A Horse at Night you write,

I love the resiliency of friendship, the way you can lose a friend and then find each other again […] I’m interested in friendships that have over time become awkward, most likely because you have both changed, and you are not as close as you once were, but you refuse to give up.

I wonder if you could speak to the themes of closeness and distance within friendship and writing?

Friendship is one of my favorite things. In a way, it’s what’s made my life what it is. As I continue to write, I can see some of my preoccupations change and some deepen. I’ve always written of closeness and of distance, more so distance, but as I continue on, I seem to want to write more about closeness. It’s harder to write about, I think, without being corny or overly sincere (let alone writing about something like love, which I am also trying to do), so it is my challenge. It’s important to me that I try. And though I’ve often written about female friendship, as in Indelicacy, I’ve also been close to people who aren’t women. I don’t want to stay stuck to what I’ve already been doing. I want to write it all.

¤

LARB Contributor

Natalie Dunn is a writer living in Brooklyn. Her fiction, poetry, and criticism have been published or will soon appear in The Believer, Triangle House, Kenyon Review Online, Adroit Journal, and elsewhere. She is the senior fiction reader at The Yale Review and a current fiction candidate at NYU.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Soul Makes Room: On Amina Cain’s “Indelicacy”

Nathan Scott McNamara considers “Indelicacy,” the new novel from Amina Cain.

Eternal Present: An Interview with Amina Cain

Kate Durbin talks to Amina Cain about her new novel, "Indelicacy."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!